When you gain a “shell” on the target system, you usually have very basic knowledge of the system. If it is a server, you already know which service you have exploited; however, you don’t necessarily know other details, such as usernames or network shares. Consequently, the shell will look like a “dark room” where you have an incomplete and vague knowledge of what’s around you. In this sense, enumeration helps you build a more complete and accurate picture.

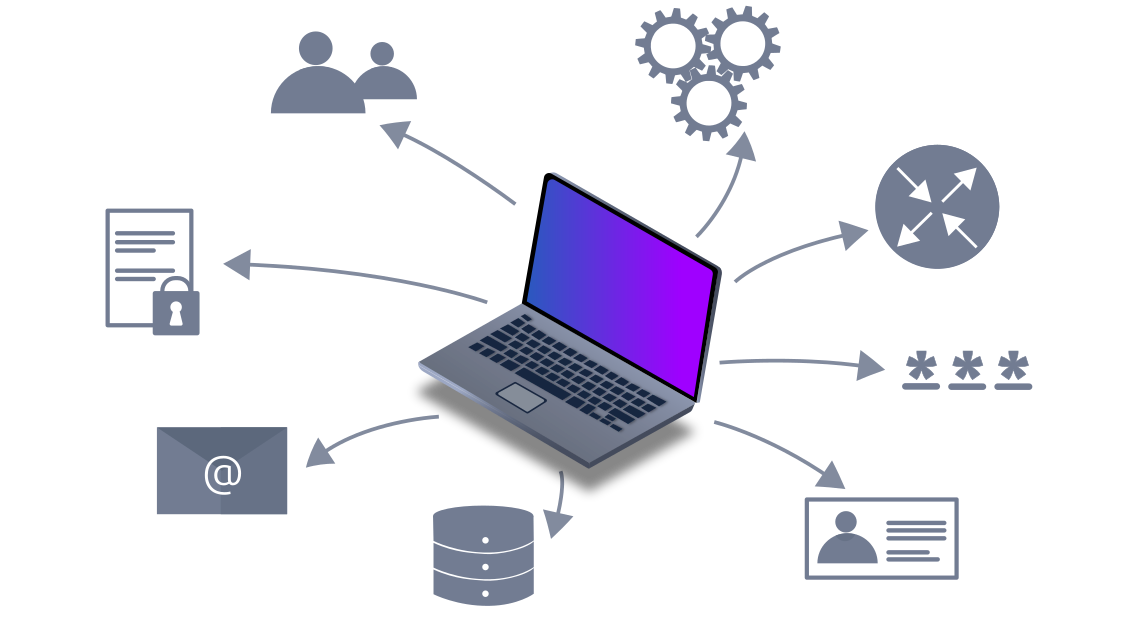

The purpose behind post-exploitation enumeration is to gather as much information about the system and its network. The exploited system might be a company desktop/laptop or a server. We aim to collect the information that would allow us to pivot to other systems on the network or to loot the current system. Some of the information we are interested in gathering include:

- Users and groups

- Hostnames

- Routing tables

- Network shares

- Network services

- Applications and banners

- Firewall configurations

- Service settings and audit configurations

- SNMP and DNS details

- Hunting for credentials (saved on web browsers or client applications)

There is no way to list everything we might stumble upon. For instance, we might find SSH keys that might grant us access to other systems. In SSH key-based authentication, we generate an SSH key pair (public and private keys); the public key is installed on a server. Consequently, the server would trust any system that can prove knowledge of the related private key.

Furthermore, we might stumble upon sensitive data saved among the user’s documents or desktop directories. Think that someone might keep a passwords.txt or passwords.xlsx instead of a proper password manager. Source code might also contain keys and passwords left lurking around, especially if the source code is not intended to be made public.