Credits to HTB Academy

Why Active Directory?

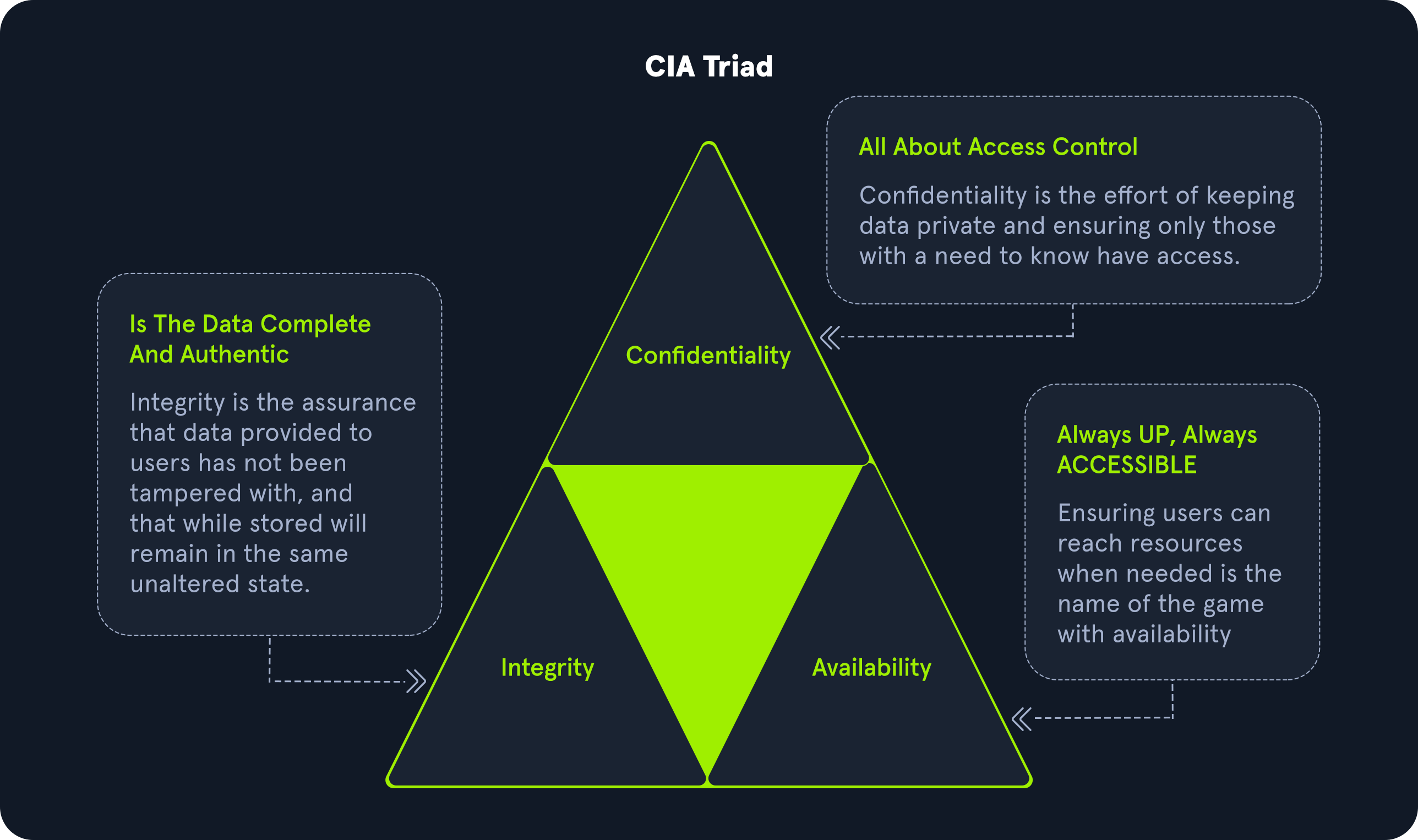

Active Directory (AD) is a directory service for Windows network environments. It is a distributed, hierarchical structure that allows for centralized management of an organization’s resources, including users, computers, groups, network devices, file shares, group policies, devices, and trusts. AD provides authentication and authorization functions within a Windows domain environment. It has come under increasing attack in recent years. It is designed to be backward-compatible, and many features are arguably not “secure by default,” and it can be easily misconfigured. This weakness can be leveraged to move laterally and vertically within a network and gain unauthorized access. AD is essentially a sizeable read-only database accessible to all users within the domain, regardless of their privilege level. A basic AD user account with no added privileges can enumerate most objects within AD. This fact makes it extremely important to properly secure an AD implementation because ANY user account, regardless of their privilege level, can be used to enumerate the domain and hunt for misconfigurations and flaws thoroughly. Also, multiple attacks can be performed with only a standard domain user account, showing the importance of a defense-in-depth strategy and careful planning focusing on security and hardening AD, network segmentation, and least privilege. One example is the noPac attack that was first released in December of 2021.

Active Directory makes information easy to find and use for administrators and users. AD is highly scalable, supports millions of objects per domain, and allows the creation of additional domains as an organization grows.

It is estimated that around 95% of Fortune 500 companies run Active Directory, making AD a key focus for attackers. A successful attack such as a phish that lands an attacker within the AD environment as a standard domain user would give them enough access to begin mapping out the domain and looking for avenues of attack. As security professionals, we will encounter AD environments of all sizes throughout our careers. It is essential to understand the structure and function of AD to become better informed as both an attacker and a defender.

Ransomware operators have been increasingly targeting Active Directory as a key part of their attack paths. The Conti Ransomware which has been used in more than 400 attacks around the world has been shown to leverage recent critical Active Directory flaws such as PrintNightmare (CVE-2021-34527) and Zerologon (CVE-2020-1472) to escalate privileges and move laterally in a target network. Understanding the structure and function of Active Directory is the first step in a career path to find and prevent these types of flaws before attackers do. Researchers are continually finding new, extremely high-risk attacks that affect Active Directory environments that often require no more than a standard domain user to obtain complete administrative control over the entire domain. There are many great open-source tools for penetration testers to enumerate and attack Active Directory. Still, to use these most effectively, we must understand how Active Directory works to identify obvious and nuanced flaws. Tools are only as effective as their operator is knowledgeable. So let’s take the time to understand the structure and function of Active Directory before moving into later modules that will focus on in-depth manual and tool-based enumeration, attacks, lateral movement, post-exploitation, and persistence.

This module will lay the foundations for starting down the path of enumerating and attacking Active Directory. We will cover, in-depth, the structure and function of AD, discuss the various AD objects, discuss user rights and privileges, tools, and processes for managing AD, and even walk through examples of setting up a small AD environment.

History of Active Directory

LDAP, the foundation of Active Directory, was first introduced in RFCs as early as 1971. Active Directory was predated by the X.500 organizational unit concept, which was the earliest version of all directory systems created by Novell and Lotus and released in 1993 as Novell Directory Services.

Active Directory was first introduced in the mid-’90s but did not become part of the Windows operating system until the release of Windows Server 2000. Microsoft first attempted to provide directory services in 1990 with the release of Windows NT 3.0. This operating system combined features of the LAN Manager protocol and the OS/2 operating systems, which Microsoft created initially along with IBM lead by Ed Iacobucci who also led the design of IBM DOS and later co-founded Citrix Systems. The NT operating system evolved throughout the 90s, adapting protocols such as LDAP and Kerberos with Microsoft’s proprietary elements. The first beta release of Active Directory was in 1997.

The release of Windows Server 2003 saw extended functionality and improved administration and added the Forest feature, which allows sysadmins to create “containers” of separate domains, users, computers, and other objects all under the same umbrella. Active Directory Federation Services (ADFS) was introduced in Server 2008 to provide Single Sign-On (SSO) to systems and applications for users on Windows Server operating systems. ADFS made it simpler and more streamlined for users to sign into applications and systems, not on their same LAN.

ADFS enables users to access applications across organizational boundaries using a single set of credentials. ADFS uses the claims-based Access Control Authorization model, which attempts to ensure security across applications by identifying users by a set of claims related to their identity, which are packaged into a security token by the identity provider.

The release of Server 2016 brought even more changes to Active Directory, such as the ability to migrate AD environments to the cloud and additional security enhancements such as user access monitoring and Group Managed Service Accounts (gMSA). gMSA offers a more secure way to run specific automated tasks, applications, and services and is often a recommended mitigation against the infamous Kerberoasting attack.

2016 saw a more significant push towards the cloud with the release of Azure AD Connect, which was designed as a single sign-on method for users being migrated to the Microsoft Office 365 environment.

Active Directory has suffered from various misconfigurations from 2000 to the present day. New vulnerabilities are discovered regularly that affect Active Directory and other technologies that interface with AD, such as Microsoft Exchange. As security researchers continue to uncover new flaws, organizations that run Active Directory need to remain on top of patching and implementing fixes. As penetration testers, we are tasked with finding these flaws for our clients before attackers.

For this reason, we must have a solid foundation in Active Directory fundamentals and understand its structure, function, the various protocols that it uses to operate, how user rights and privileges are managed, how sysadmins administer AD and the multitude of vulnerabilities and misconfigurations that can be present in an AD environment. Managing AD is no easy task. One change/fix can introduce additional issues elsewhere. Before beginning to enumerate and then attack Active Directory, let’s cover foundational concepts that will follow us throughout our infosec careers.

As said before, 95% of Fortune 500 companies run Active Directory, and Microsoft has a near-complete monopoly in the directory services space. Even though many companies are transitioning to cloud and hybrid environments, on-prem AD is not going away for many companies. If you are performing network penetration testing engagements, you can be nearly sure to encounter AD in some way on almost all of them.

This fundamental knowledge will make us better attackers and give us insight into AD that will be extremely useful when providing remediation advice to our clients. A deep understanding of AD will make peeling back the layers less daunting, and we will have the same confidence when approaching an environment with 10,000 hosts as we do with one with 20.

Active Directory Structure

Active Directory (AD) is a directory service for Windows network environments. It is a distributed, hierarchical structure that allows for centralized management of an organization’s resources, including users, computers, groups, network devices and file shares, group policies, servers and workstations, and trusts. AD provides authentication and authorization functions within a Windows domain environment. A directory service, such as Active Directory Domain Services (AD DS) gives an organization ways to store directory data and make it available to both standard users and administrators on the same network. AD DS stores information such as usernames and passwords and manages the rights needed for authorized users to access this information. It was first shipped with Windows Server 2000; it has come under increasing attack in recent years. It is designed to be backward-compatible, and many features are arguably not “secure by default.” It is difficult to manage properly, especially in large environments where it can be easily misconfigured.

Active Directory flaws and misconfigurations can often be used to obtain a foothold (internal access), move laterally and vertically within a network, and gain unauthorized access to protected resources such as databases, file shares, source code, and more. AD is essentially a large database accessible to all users within the domain, regardless of their privilege level. A basic AD user account with no added privileges can be used to enumerate the majority of objects contained within AD, including but not limited to:

| Domain Computers | Domain Users |

|---|---|

| Domain Group Information | Organizational Units (OUs) |

| Default Domain Policy | Functional Domain Levels |

| Password Policy | Group Policy Objects (GPOs) |

| Domain Trusts | Access Control Lists (ACLs) |

For this reason, we must understand how Active Directory is set up and the basics of administration before attempting to attack it. It’s always easier to “break” things if we already know how to build them.

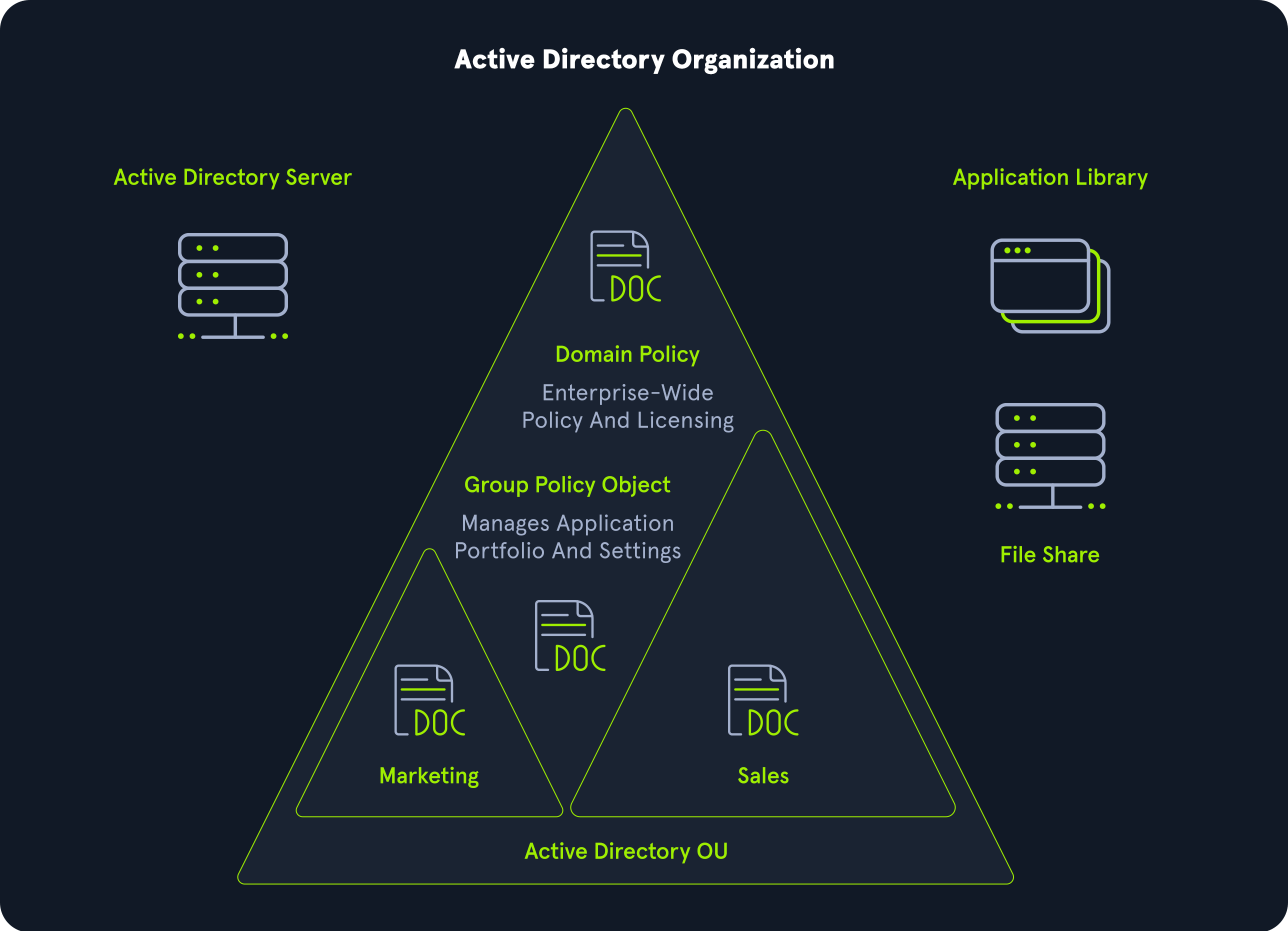

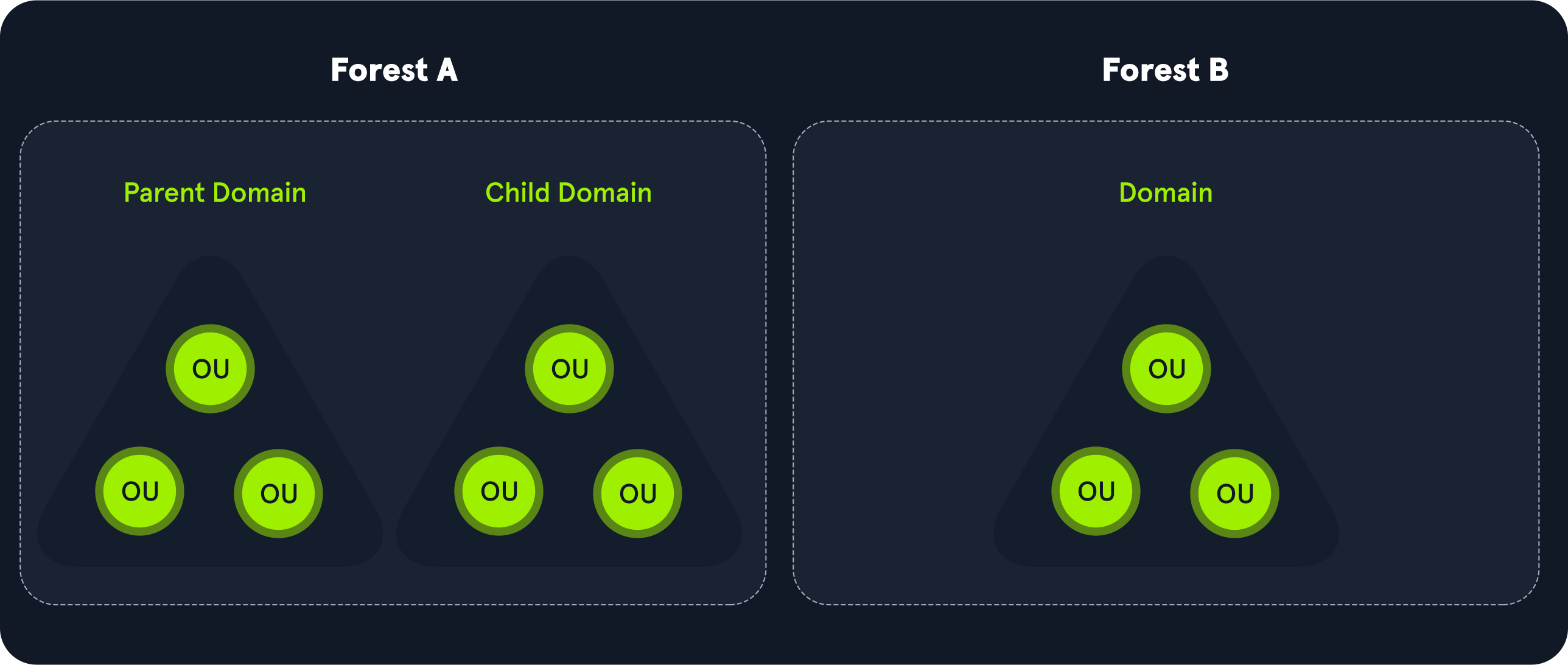

Active Directory is arranged in a hierarchical tree structure, with a forest at the top containing one or more domains, which can themselves have nested subdomains. A forest is the security boundary within which all objects are under administrative control. A forest may contain multiple domains, and a domain may include further child or sub-domains. A domain is a structure within which contained objects (users, computers, and groups) are accessible. It has many built-in Organizational Units (OUs), such as Domain Controllers, Users, Computers, and new OUs can be created as required. OUs may contain objects and sub-OUs, allowing for the assignment of different group policies.

At a very (simplistic) high level, an AD structure may look as follows:

INLANEFREIGHT.LOCAL/

├── ADMIN.INLANEFREIGHT.LOCAL

│ ├── GPOs

│ └── OU

│ └── EMPLOYEES

│ ├── COMPUTERS

│ │ └── FILE01

│ ├── GROUPS

│ │ └── HQ Staff

│ └── USERS

│ └── barbara.jones

├── CORP.INLANEFREIGHT.LOCAL

└── DEV.INLANEFREIGHT.LOCALHere we could say that INLANEFREIGHT.LOCAL is the root domain and contains the subdomains (either child or tree root domains) ADMIN.INLANEFREIGHT.LOCAL, CORP.INLANEFREIGHT.LOCAL, and DEV.INLANEFREIGHT.LOCAL as well as the other objects that make up a domain such as users, groups, computers, and more as we will see in detail below. It is common to see multiple domains (or forests) linked together via trust relationships in organizations that perform a lot of acquisitions. It is often quicker and easier to create a trust relationship with another domain/forest than recreate all new users in the current domain. As we will see in later modules, domain trusts can introduce a slew of security issues if not appropriately administered.

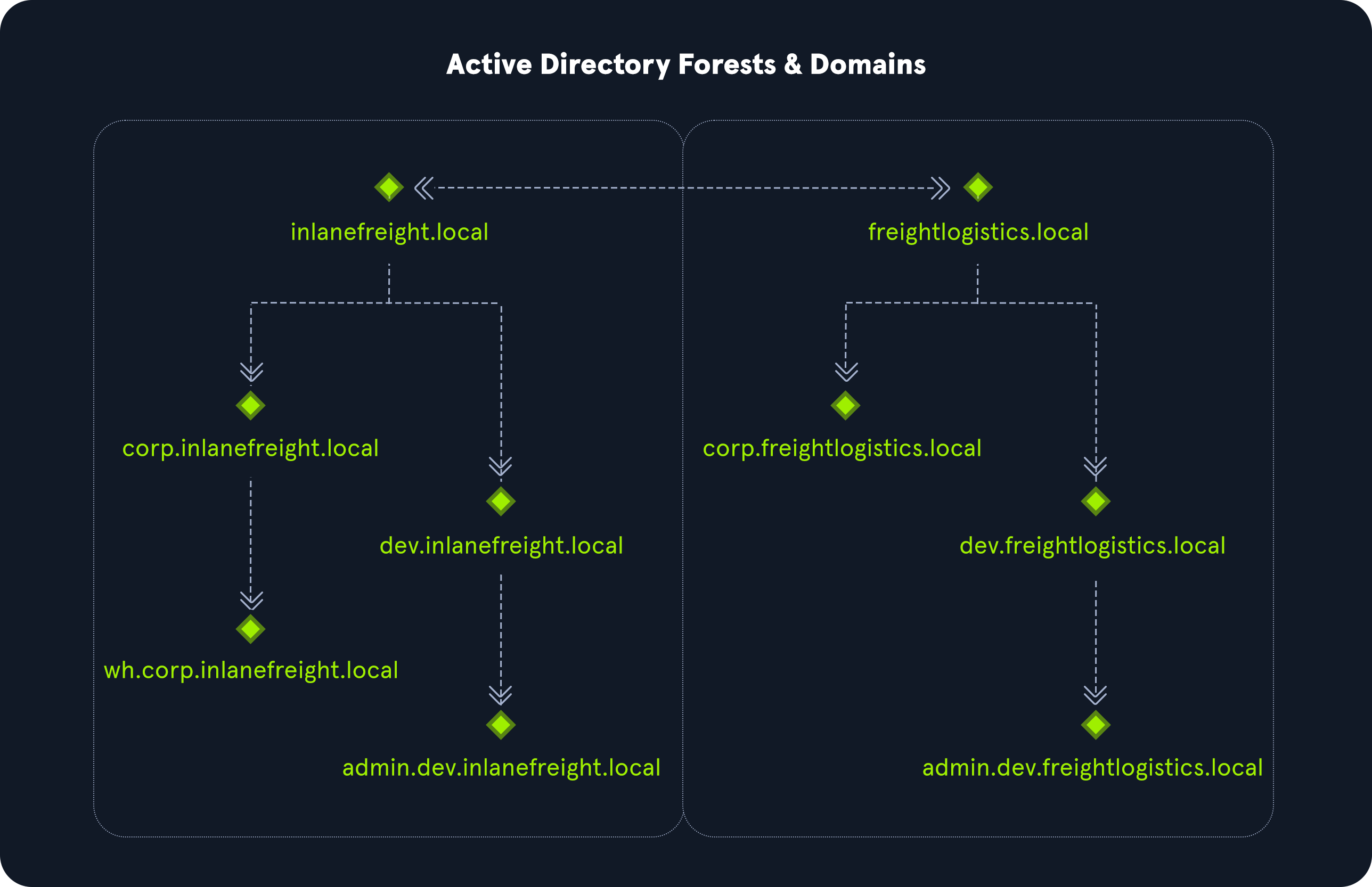

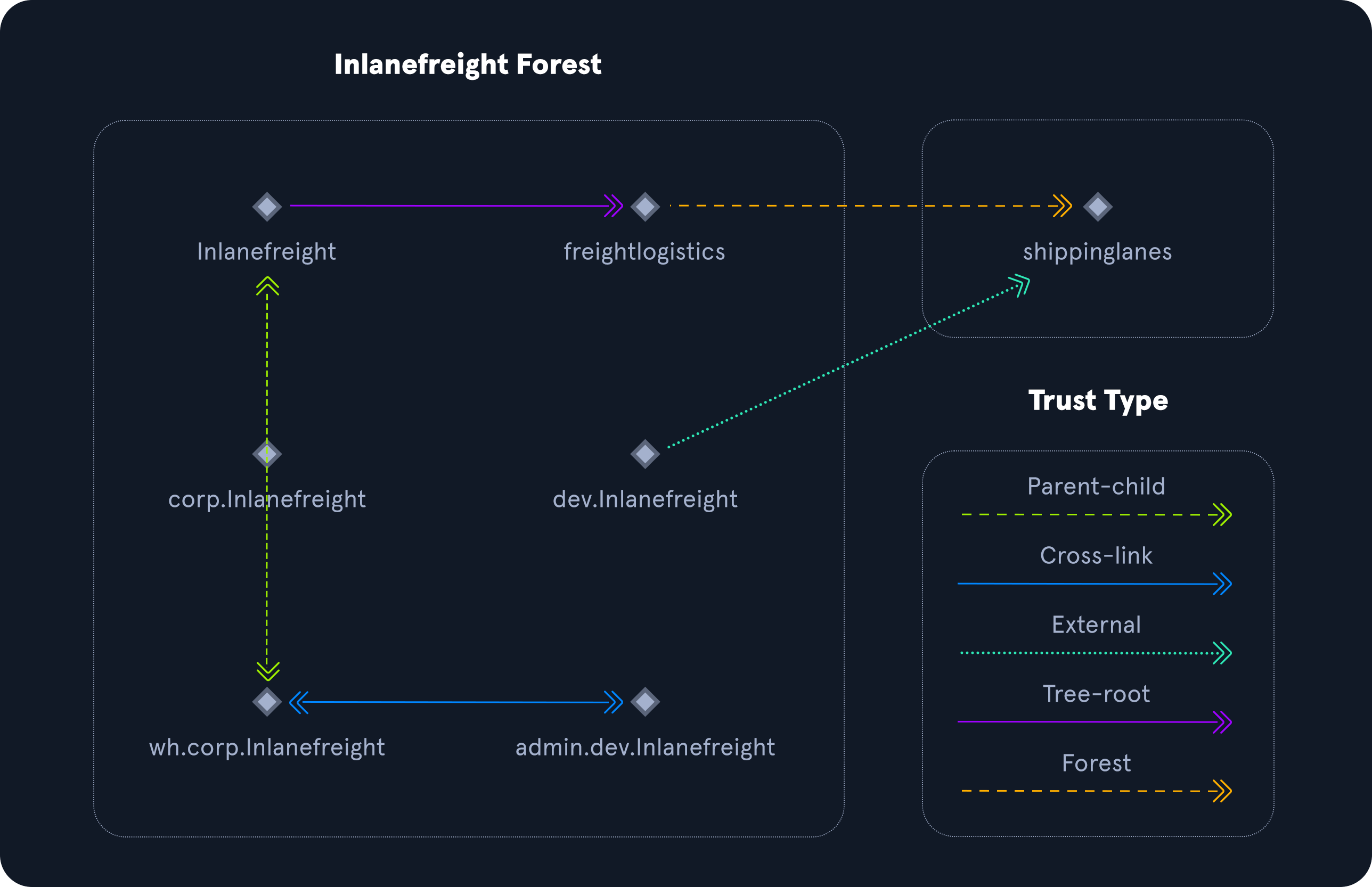

The graphic below shows two forests, INLANEFREIGHT.LOCAL and FREIGHTLOGISTICS.LOCAL. The two-way arrow represents a bidirectional trust between the two forests, meaning that users in INLANEFREIGHT.LOCAL can access resources in FREIGHTLOGISTICS.LOCAL and vice versa. We can also see multiple child domains under each root domain. In this example, we can see that the root domain trusts each of the child domains, but the child domains in forest A do not necessarily have trusts established with the child domains in forest B. This means that a user that is part of admin.dev.freightlogistics.local would NOT be able to authenticate to machines in the wh.corp.inlanefreight.local domain by default even though a bidirectional trust exists between the top-level inlanefreight.local and freightlogistics.local domains. To allow direct communication from admin.dev.freightlogistics.local and wh.corp.inlanefreight.local, another trust would need to be set up.

Active Directory Terminology

Before we go any further, let’s take a step back and define some key terminology that will be used throughout this module and in general when dealing with Active Directory in any capacity.

Object

An object can be defined as ANY resource present within an Active Directory environment such as OUs, printers, users, domain controllers, etc.

Attributes

Every object in Active Directory has an associated set of attributes used to define characteristics of the given object. A computer object contains attributes such as the hostname and DNS name. All attributes in AD have an associated LDAP name that can be used when performing LDAP queries, such as displayName for Full Name and given name for First Name.

Schema

The Active Directory schema is essentially the blueprint of any enterprise environment. It defines what types of objects can exist in the AD database and their associated attributes. It lists definitions corresponding to AD objects and holds information about each object. For example, users in AD belong to the class “user,” and computer objects to “computer,” and so on. Each object has its own information (some required to be set and others optional) that are stored in Attributes. When an object is created from a class, this is called instantiation, and an object created from a specific class is called an instance of that class. For example, if we take the computer RDS01. This computer object is an instance of the “computer” class in Active Directory.

Domain

A domain is a logical group of objects such as computers, users, OUs, groups, etc. We can think of each domain as a different city within a state or country. Domains can operate entirely independently of one another or be connected via trust relationships.

Forest

A forest is a collection of Active Directory domains. It is the topmost container and contains all of the AD objects introduced below, including but not limited to domains, users, groups, computers, and Group Policy objects. A forest can contain one or multiple domains and be thought of as a state in the US or a country within the EU. Each forest operates independently but may have various trust relationships with other forests.

Tree

A tree is a collection of Active Directory domains that begins at a single root domain. A forest is a collection of AD trees. Each domain in a tree shares a boundary with the other domains. A parent-child trust relationship is formed when a domain is added under another domain in a tree. Two trees in the same forest cannot share a name (namespace). Let’s say we have two trees in an AD forest: inlanefreight.local and ilfreight.local. A child domain of the first would be corp.inlanefreight.local while a child domain of the second could be corp.ilfreight.local. All domains in a tree share a standard Global Catalog which contains all information about objects that belong to the tree.

Container

Container objects hold other objects and have a defined place in the directory subtree hierarchy.

Leaf

Leaf objects do not contain other objects and are found at the end of the subtree hierarchy.

Global Unique Identifier (GUID)

A GUID is a unique 128-bit value assigned when a domain user or group is created. This GUID value is unique across the enterprise, similar to a MAC address. Every single object created by Active Directory is assigned a GUID, not only user and group objects. The GUID is stored in the ObjectGUID attribute. When querying for an AD object (such as a user, group, computer, domain, domain controller, etc.), we can query for its objectGUID value using PowerShell or search for it by specifying its distinguished name, GUID, SID, or SAM account name. GUIDs are used by AD to identify objects internally. Searching in Active Directory by GUID value is probably the most accurate and reliable way to find the exact object you are looking for, especially if the global catalog may contain similar matches for an object name. Specifying the ObjectGUID value when performing AD enumeration will ensure that we get the most accurate results pertaining to the object we are searching for information about. The ObjectGUID property never changes and is associated with the object for as long as that object exists in the domain.

Security principals

Security principals are anything that the operating system can authenticate, including users, computer accounts, or even threads/processes that run in the context of a user or computer account (i.e., an application such as Tomcat running in the context of a service account within the domain). In AD, security principles are domain objects that can manage access to other resources within the domain. We can also have local user accounts and security groups used to control access to resources on only that specific computer. These are not managed by AD but rather by the Security Accounts Manager (SAM).

Security Identifier (SID)

A security identifier, or SID is used as a unique identifier for a security principal or security group. Every account, group, or process has its own unique SID, which, in an AD environment, is issued by the domain controller and stored in a secure database. A SID can only be used once. Even if the security principle is deleted, it can never be used again in that environment to identify another user or group. When a user logs in, the system creates an access token for them which contains the user’s SID, the rights they have been granted, and the SIDs for any groups that the user is a member of. This token is used to check rights whenever the user performs an action on the computer. There are also well-known SIDs that are used to identify generic users and groups. These are the same across all operating systems. An example is the Everyone group.

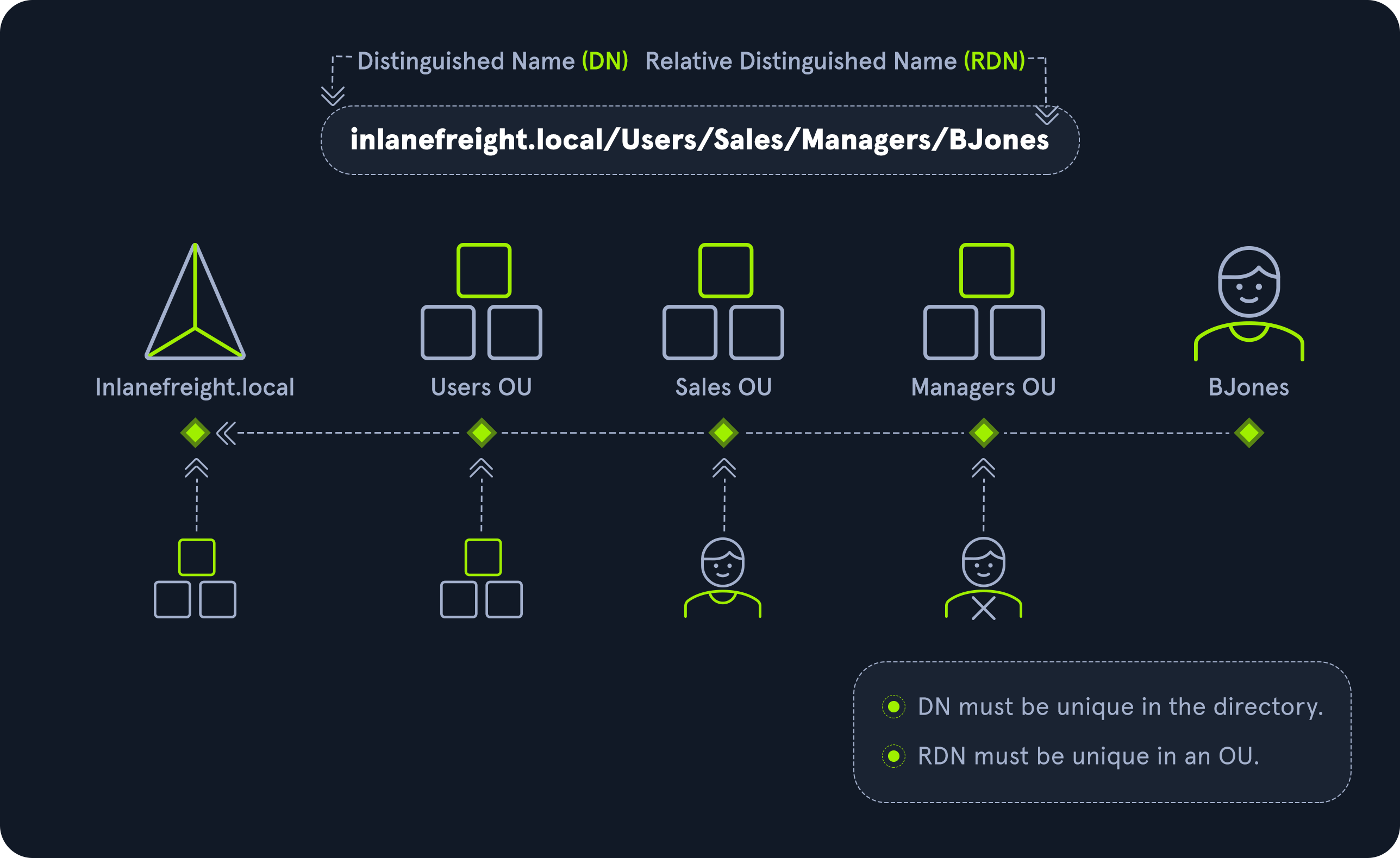

Distinguished Name (DN)

A Distinguished Name (DN) describes the full path to an object in AD (such as cn=bjones, ou=IT, ou=Employees, dc=inlanefreight, dc=local). In this example, the user bjones works in the IT department of the company Inlanefreight, and his account is created in an Organizational Unit (OU) that holds accounts for company employees. The Common Name (CN) bjones is just one way the user object could be searched for or accessed within the domain.

Relative Distinguished Name (RDN)

A Relative Distinguished Name (RDN) is a single component of the Distinguished Name that identifies the object as unique from other objects at the current level in the naming hierarchy. In our example, bjones is the Relative Distinguished Name of the object. AD does not allow two objects with the same name under the same parent container, but there can be two objects with the same RDNs that are still unique in the domain because they have different DNs. For example, the object cn=bjones,dc=dev,dc=inlanefreight,dc=local would be recognized as different from cn=bjones,dc=inlanefreight,dc=local.

sAMAccountName

The sAMAccountName is the user’s logon name. Here it would just be bjones. It must be a unique value and 20 or fewer characters.

userPrincipalName

The userPrincipalName attribute is another way to identify users in AD. This attribute consists of a prefix (the user account name) and a suffix (the domain name) in the format of bjones@inlanefreight.local. This attribute is not mandatory.

FSMO Roles

In the early days of AD, if you had multiple DCs in an environment, they would fight over which DC gets to make changes, and sometimes changes would not be made properly. Microsoft then implemented “last writer wins,” which could introduce its own problems if the last change breaks things. They then introduced a model in which a single “master” DC could apply changes to the domain while the others merely fulfilled authentication requests. This was a flawed design because if the master DC went down, no changes could be made to the environment until it was restored. To resolve this single point of failure model, Microsoft separated the various responsibilities that a DC can have into Flexible Single Master Operation (FSMO) roles. These give Domain Controllers (DC) the ability to continue authenticating users and granting permissions without interruption (authorization and authentication). There are five FSMO roles: Schema Master and Domain Naming Master (one of each per forest), Relative ID (RID) Master (one per domain), Primary Domain Controller (PDC) Emulator (one per domain), and Infrastructure Master (one per domain). All five roles are assigned to the first DC in the forest root domain in a new AD forest. Each time a new domain is added to a forest, only the RID Master, PDC Emulator, and Infrastructure Master roles are assigned to the new domain. FSMO roles are typically set when domain controllers are created, but sysadmins can transfer these roles if needed. These roles help replication in AD to run smoothly and ensure that critical services are operating correctly. We will walk through each of these roles in detail later in this section.

Global Catalog

A global catalog (GC) is a domain controller that stores copies of ALL objects in an Active Directory forest. The GC stores a full copy of all objects in the current domain and a partial copy of objects that belong to other domains in the forest. Standard domain controllers hold a complete replica of objects belonging to its domain but not those of different domains in the forest. The GC allows both users and applications to find information about any objects in ANY domain in the forest. GC is a feature that is enabled on a domain controller and performs the following functions:

- Authentication (provided authorization for all groups that a user account belongs to, which is included when an access token is generated)

- Object search (making the directory structure within a forest transparent, allowing a search to be carried out across all domains in a forest by providing just one attribute about an object.)

Read-Only Domain Controller (RODC)

A Read-Only Domain Controller (RODC) has a read-only Active Directory database. No AD account passwords are cached on an RODC (other than the RODC computer account & RODC KRBTGT passwords.) No changes are pushed out via an RODC’s AD database, SYSVOL, or DNS. RODCs also include a read-only DNS server, allow for administrator role separation, reduce replication traffic in the environment, and prevent SYSVOL modifications from being replicated to other DCs.

Replication

Replication happens in AD when AD objects are updated and transferred from one Domain Controller to another. Whenever a DC is added, connection objects are created to manage replication between them. These connections are made by the Knowledge Consistency Checker (KCC) service, which is present on all DCs. Replication ensures that changes are synchronized with all other DCs in a forest, helping to create a backup in case one domain controller fails.

Service Principal Name (SPN)

A Service Principal Name (SPN) uniquely identifies a service instance. They are used by Kerberos authentication to associate an instance of a service with a logon account, allowing a client application to request the service to authenticate an account without needing to know the account name.

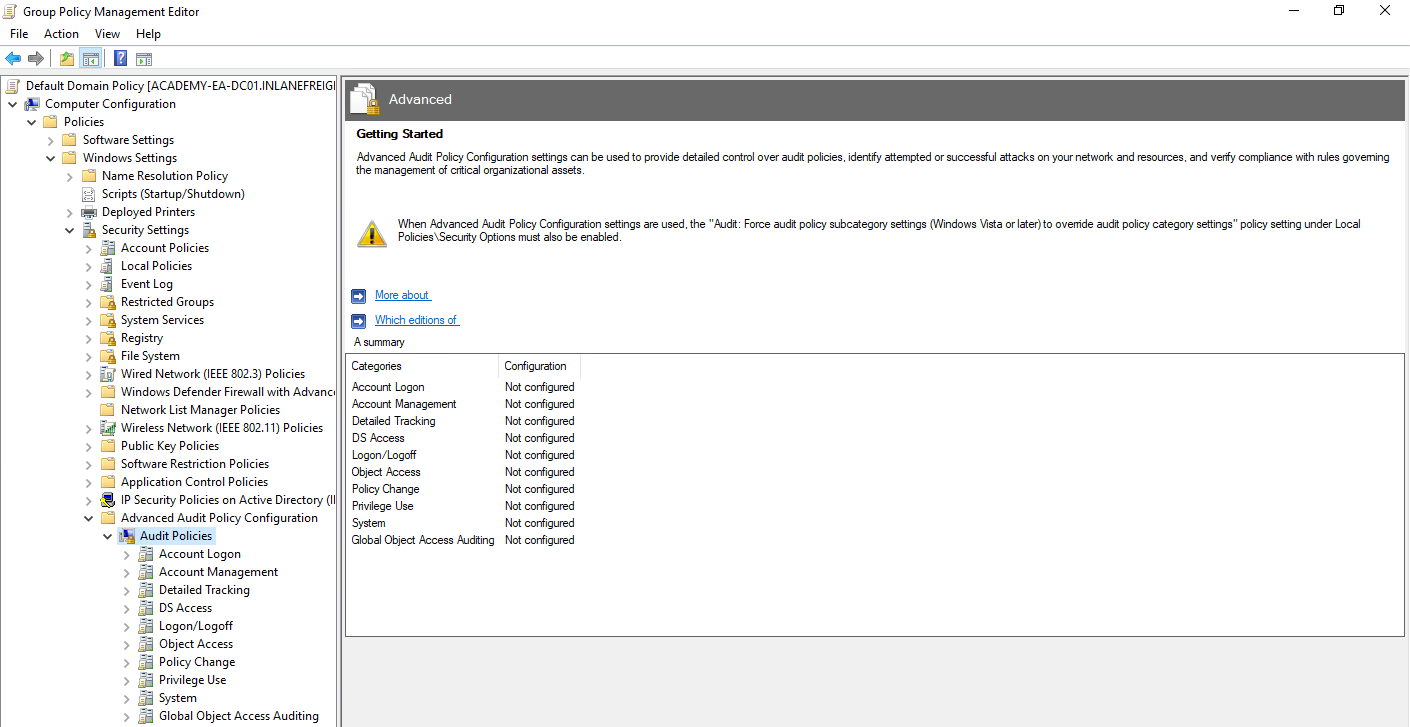

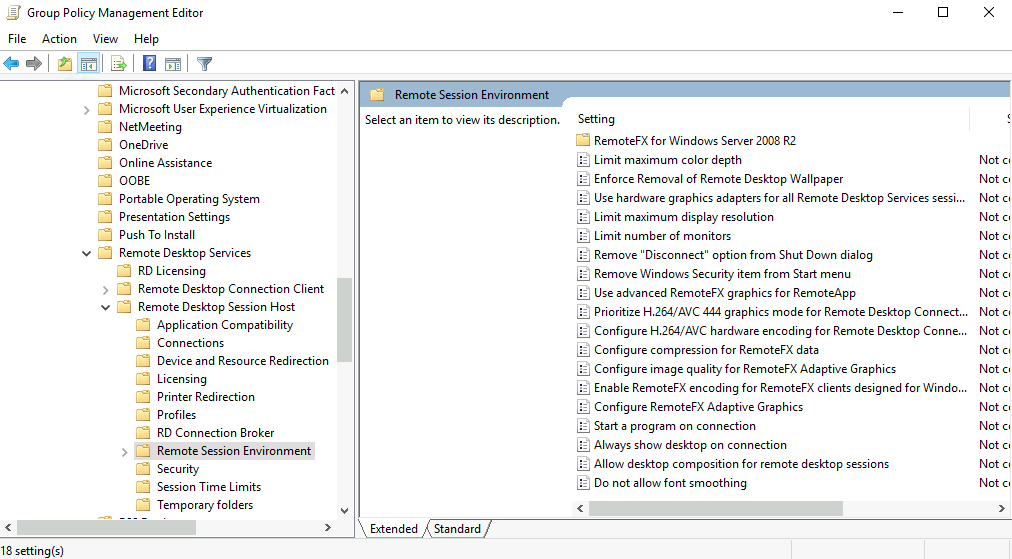

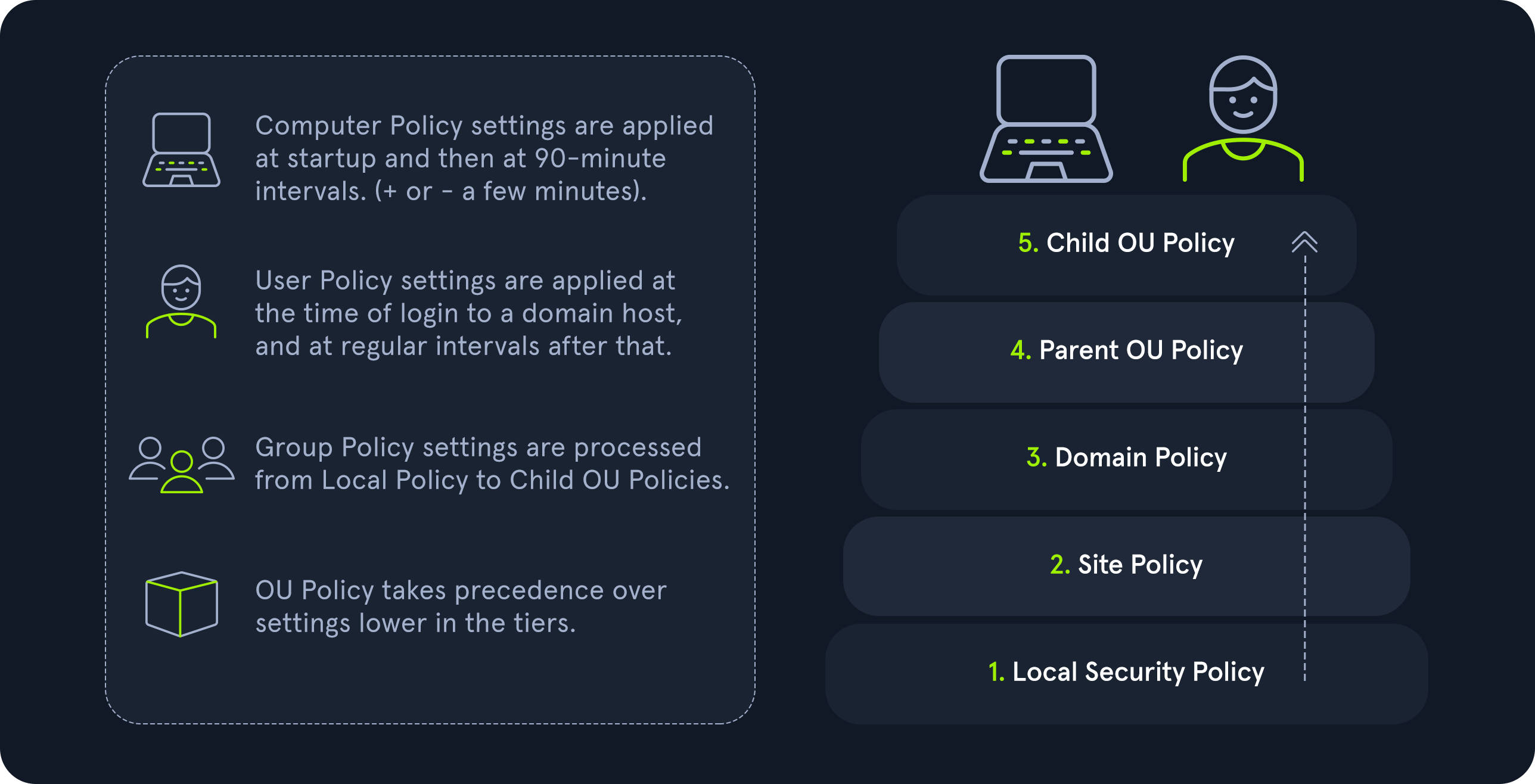

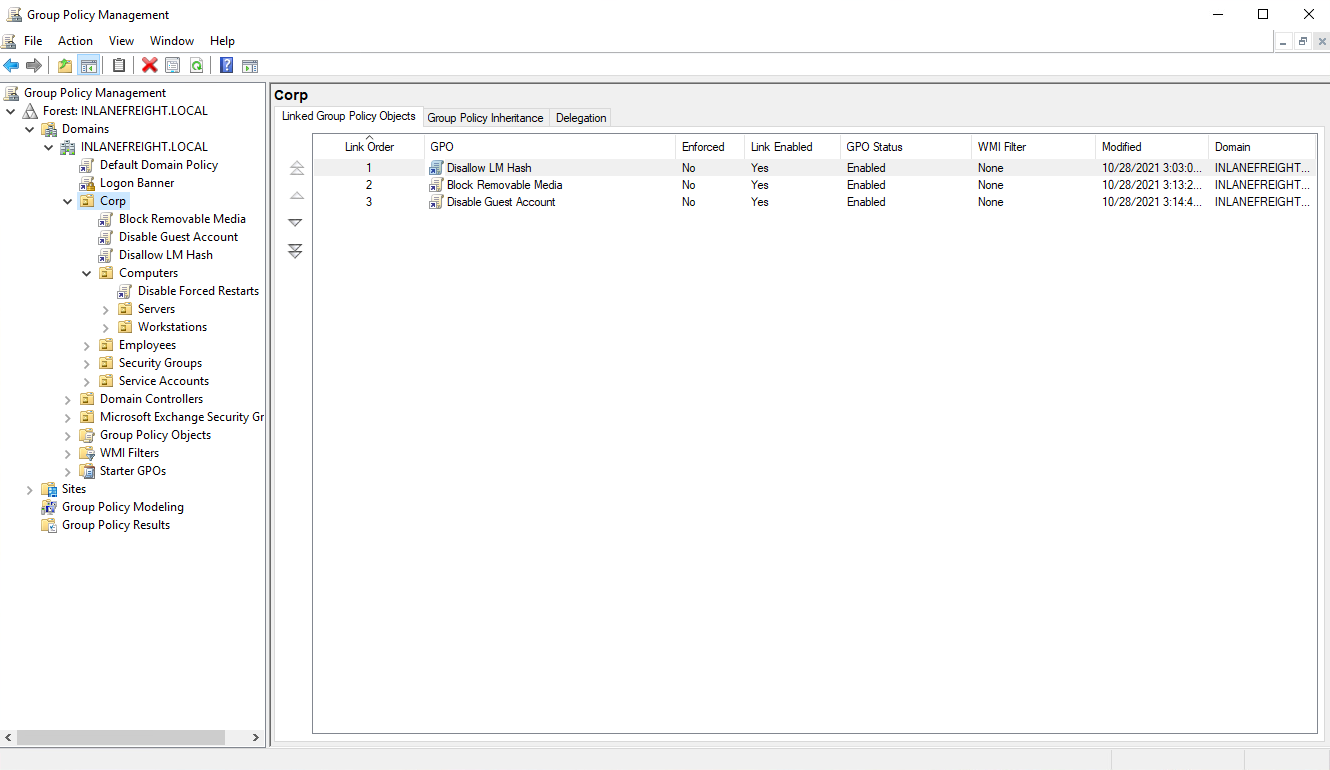

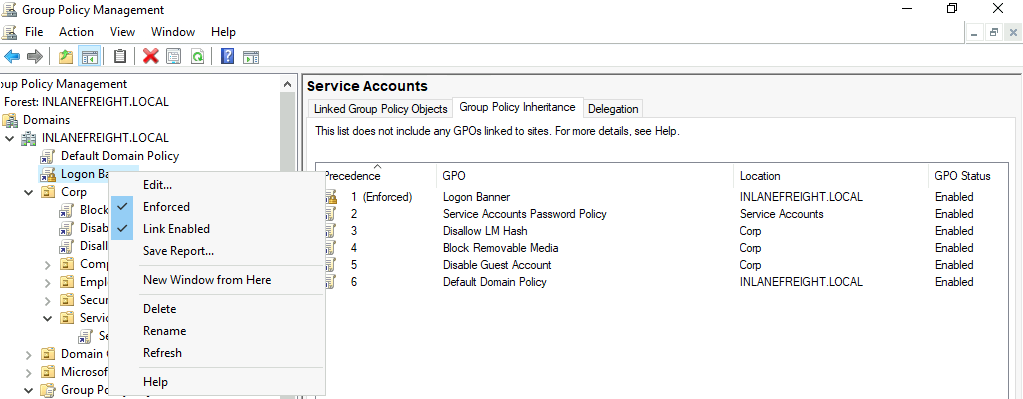

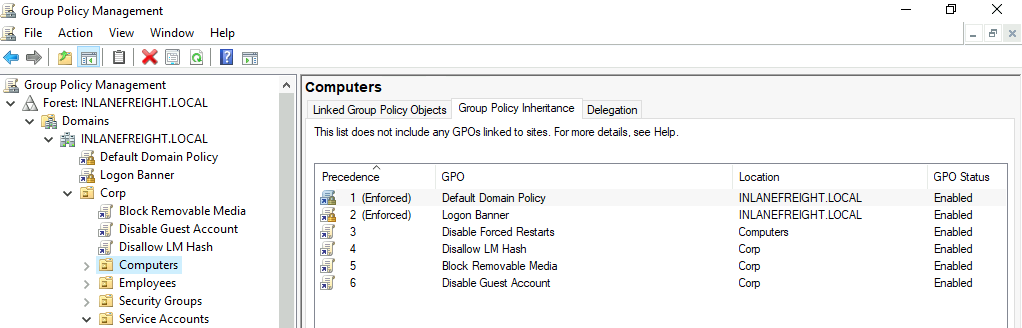

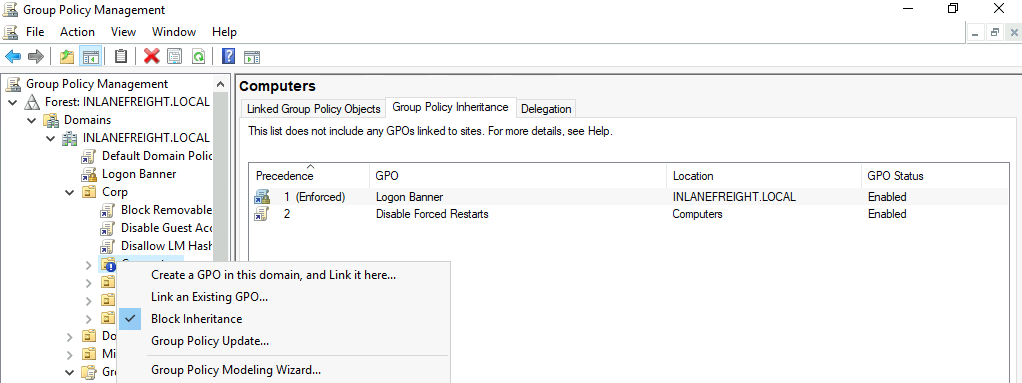

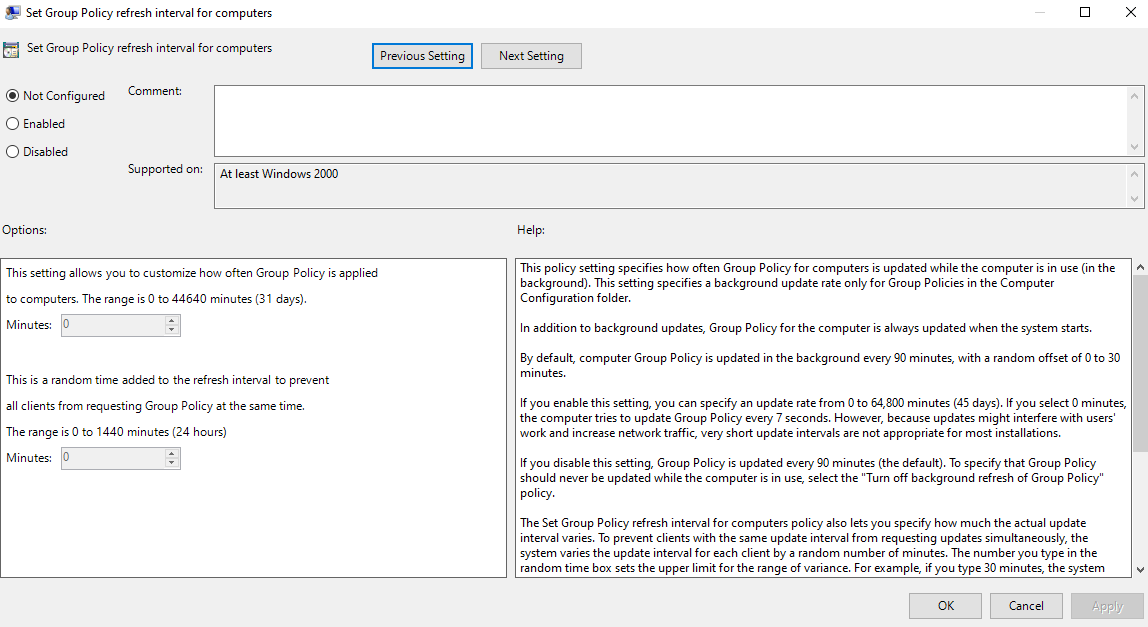

Group Policy Object (GPO)

Group Policy Objects (GPOs) are virtual collections of policy settings. Each GPO has a unique GUID. A GPO can contain local file system settings or Active Directory settings. GPO settings can be applied to both user and computer objects. They can be applied to all users and computers within the domain or defined more granularly at the OU level.

Access Control List (ACL)

An Access Control List (ACL) is the ordered collection of Access Control Entries (ACEs) that apply to an object.

Access Control Entries (ACEs)

Each Access Control Entry (ACE) in an ACL identifies a trustee (user account, group account, or logon session) and lists the access rights that are allowed, denied, or audited for the given trustee.

Discretionary Access Control List (DACL)

DACLs define which security principles are granted or denied access to an object; it contains a list of ACEs. When a process tries to access a securable object, the system checks the ACEs in the object’s DACL to determine whether or not to grant access. If an object does NOT have a DACL, then the system will grant full access to everyone, but if the DACL has no ACE entries, the system will deny all access attempts. ACEs in the DACL are checked in sequence until a match is found that allows the requested rights or until access is denied.

System Access Control Lists (SACL)

Allows for administrators to log access attempts that are made to secured objects. ACEs specify the types of access attempts that cause the system to generate a record in the security event log.

Fully Qualified Domain Name (FQDN)

An FQDN is the complete name for a specific computer or host. It is written with the hostname and domain name in the format [host name].[domain name].[tld]. This is used to specify an object’s location in the tree hierarchy of DNS. The FQDN can be used to locate hosts in an Active Directory without knowing the IP address, much like when browsing to a website such as google.com instead of typing in the associated IP address. An example would be the host DC01 in the domain INLANEFREIGHT.LOCAL. The FQDN here would be DC01.INLANEFREIGHT.LOCAL.

Tombstone

A tombstone is a container object in AD that holds deleted AD objects. When an object is deleted from AD, the object remains for a set period of time known as the Tombstone Lifetime, and the isDeleted attribute is set to TRUE. Once an object exceeds the Tombstone Lifetime, it will be entirely removed. Microsoft recommends a tombstone lifetime of 180 days to increase the usefulness of backups, but this value may differ across environments. Depending on the DC operating system version, this value will default to 60 or 180 days. If an object is deleted in a domain that does not have an AD Recycle Bin, it will become a tombstone object. When this happens, the object is stripped of most of its attributes and placed in the Deleted Objects container for the duration of the tombstoneLifetime. It can be recovered, but any attributes that were lost can no longer be recovered.

AD Recycle Bin

The AD Recycle Bin was first introduced in Windows Server 2008 R2 to facilitate the recovery of deleted AD objects. This made it easier for sysadmins to restore objects, avoiding the need to restore from backups, restarting Active Directory Domain Services (AD DS), or rebooting a Domain Controller. When the AD Recycle Bin is enabled, any deleted objects are preserved for a period of time, facilitating restoration if needed. Sysadmins can set how long an object remains in a deleted, recoverable state. If this is not specified, the object will be restorable for a default value of 60 days. The biggest advantage of using the AD Recycle Bin is that most of a deleted object’s attributes are preserved, which makes it far easier to fully restore a deleted object to its previous state.

SYSVOL

The SYSVOL folder, or share, stores copies of public files in the domain such as system policies, Group Policy settings, logon/logoff scripts, and often contains other types of scripts that are executed to perform various tasks in the AD environment. The contents of the SYSVOL folder are replicated to all DCs within the environment using File Replication Services (FRS). You can read more about the SYSVOL structure here.

AdminSDHolder

The AdminSDHolder object is used to manage ACLs for members of built-in groups in AD marked as privileged. It acts as a container that holds the Security Descriptor applied to members of protected groups. The SDProp (SD Propagator) process runs on a schedule on the PDC Emulator Domain Controller. When this process runs, it checks members of protected groups to ensure that the correct ACL is applied to them. It runs every hour by default. For example, suppose an attacker is able to create a malicious ACL entry to grant a user certain rights over a member of the Domain Admins group. In that case, unless they modify other settings in AD, these rights will be removed (and they will lose any persistence they were hoping to achieve) when the SDProp process runs on the set interval.

dsHeuristics

The dsHeuristics attribute is a string value set on the Directory Service object used to define multiple forest-wide configuration settings. One of these settings is to exclude built-in groups from the Protected Groups list. Groups in this list are protected from modification via the AdminSDHolder object. If a group is excluded via the dsHeuristics attribute, then any changes that affect it will not be reverted when the SDProp process runs.

adminCount

The adminCount attribute determines whether or not the SDProp process protects a user. If the value is set to 0 or not specified, the user is not protected. If the attribute value is set to 1, the user is protected. Attackers will often look for accounts with the adminCount attribute set to 1 to target in an internal environment. These are often privileged accounts and may lead to further access or full domain compromise.

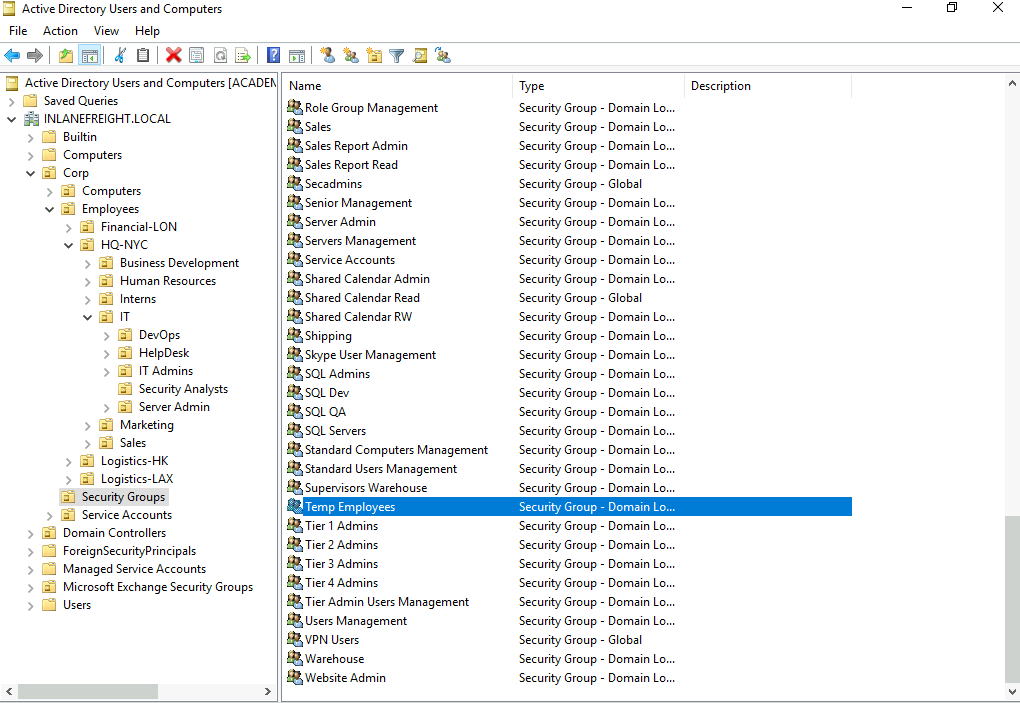

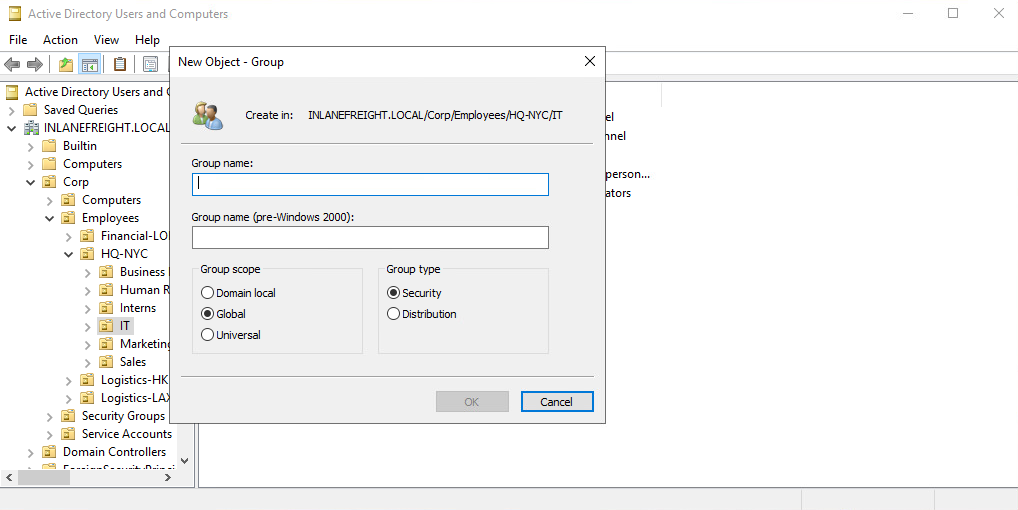

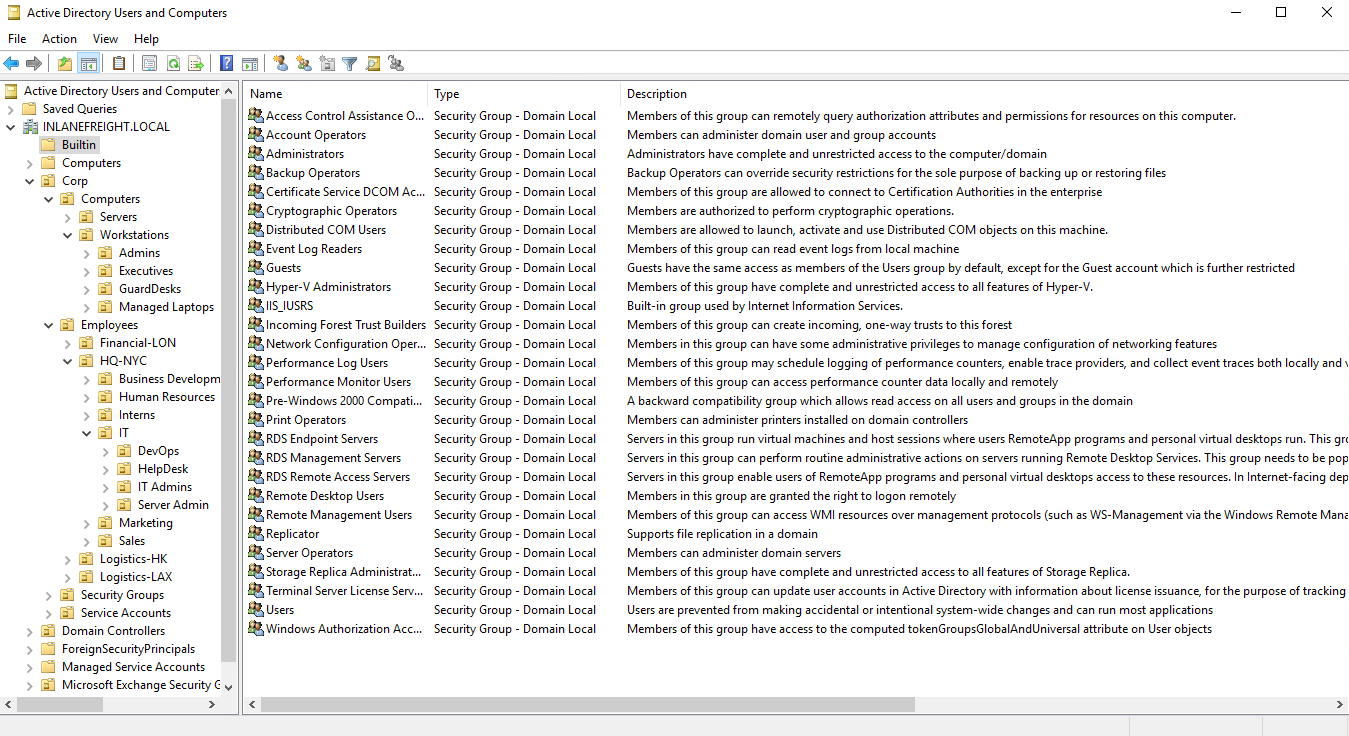

Active Directory Users and Computers (ADUC)

ADUC is a GUI console commonly used for managing users, groups, computers, and contacts in AD. Changes made in ADUC can be done via PowerShell as well.

ADSI Edit

ADSI Edit is a GUI tool used to manage objects in AD. It provides access to far more than is available in ADUC and can be used to set or delete any attribute available on an object, add, remove, and move objects as well. It is a powerful tool that allows a user to access AD at a much deeper level. Great care should be taken when using this tool, as changes here could cause major problems in AD.

sIDHistory

This attribute holds any SIDs that an object was assigned previously. It is usually used in migrations so a user can maintain the same level of access when migrated from one domain to another. This attribute can potentially be abused if set insecurely, allowing an attacker to gain prior elevated access that an account had before a migration if SID Filtering (or removing SIDs from another domain from a user’s access token that could be used for elevated access) is not enabled.

NTDS.DIT

The NTDS.DIT file can be considered the heart of Active Directory. It is stored on a Domain Controller at C:\Windows\NTDS\ and is a database that stores AD data such as information about user and group objects, group membership, and, most important to attackers and penetration testers, the password hashes for all users in the domain. Once full domain compromise is reached, an attacker can retrieve this file, extract the hashes, and either use them to perform a pass-the-hash attack or crack them offline using a tool such as Hashcat to access additional resources in the domain. If the setting Store password with reversible encryption is enabled, then the NTDS.DIT will also store the cleartext passwords for all users created or who changed their password after this policy was set. While rare, some organizations may enable this setting if they use applications or protocols that need to use a user’s existing password (and not Kerberos) for authentication.

MSBROWSE

MSBROWSE is a Microsoft networking protocol that was used in early versions of Windows-based local area networks (LANs) to provide browsing services. It was used to maintain a list of resources, such as shared printers and files, that were available on the network, and to allow users to easily browse and access these resources.

In older version of Windows we could use nbtstat -A ip-address to search for the Master Browser. If we see MSBROWSE it means that’s the Master Browser. Aditionally we could use nltest utility to query a Windows Master Browser for the names of the Domain Controllers.

Today, MSBROWSE is largely obsolete and is no longer in widespread use. Modern Windows-based LANs use the Server Message Block (SMB) protocol for file and printer sharing, and the Common Internet File System (CIFS) protocol for browsing services.

Active Directory Objects

We will often see the term “objects” when referring to AD. What is an object? An object can be defined as ANY resource present within an Active Directory environment such as OUs, printers, users, domain controllers.

AD Objects

Users

These are the users within the organization’s AD environment. Users are considered leaf objects, which means that they cannot contain any other objects within them. Another example of a leaf object is a mailbox in Microsoft Exchange. A user object is considered a security principal and has a security identifier (SID) and a global unique identifier (GUID). User objects have many possible attributes, such as their display name, last login time, date of last password change, email address, account description, manager, address, and more. Depending on how a particular Active Directory environment is set up, there can be over 800 possible user attributes when accounting for ALL possible attributes as detailed here. This example goes far beyond what is typically populated for a standard user in most environments but shows Active Directory’s sheer size and complexity. They are a crucial target for attackers since gaining access to even a low privileged user can grant access to many objects and resources and allow for detailed enumeration of the entire domain (or forest).

Contacts

A contact object is usually used to represent an external user and contains informational attributes such as first name, last name, email address, telephone number, etc. They are leaf objects and are NOT security principals (securable objects), so they don’t have a SID, only a GUID. An example would be a contact card for a third-party vendor or a customer.

Printers

A printer object points to a printer accessible within the AD network. Like a contact, a printer is a leaf object and not a security principal, so it only has a GUID. Printers have attributes such as the printer’s name, driver information, port number, etc.

Computers

A computer object is any computer joined to the AD network (workstation or server). Computers are leaf objects because they do not contain other objects. However, they are considered security principals and have a SID and a GUID. Like users, they are prime targets for attackers since full administrative access to a computer (as the all-powerful NT AUTHORITY\SYSTEM account) grants similar rights to a standard domain user and can be used to perform the majority of the enumeration tasks that a user account can (save for a few exceptions across domain trusts.)

Shared Folders

A shared folder object points to a shared folder on the specific computer where the folder resides. Shared folders can have stringent access control applied to them and can be either accessible to everyone (even those without a valid AD account), open to only authenticated users (which means anyone with even the lowest privileged user account OR a computer account (NT AUTHORITY\SYSTEM) could access it), or be locked down to only allow certain users/groups access. Anyone not explicitly allowed access will be denied from listing or reading its contents. Shared folders are NOT security principals and only have a GUID. A shared folder’s attributes can include the name, location on the system, security access rights.

Groups

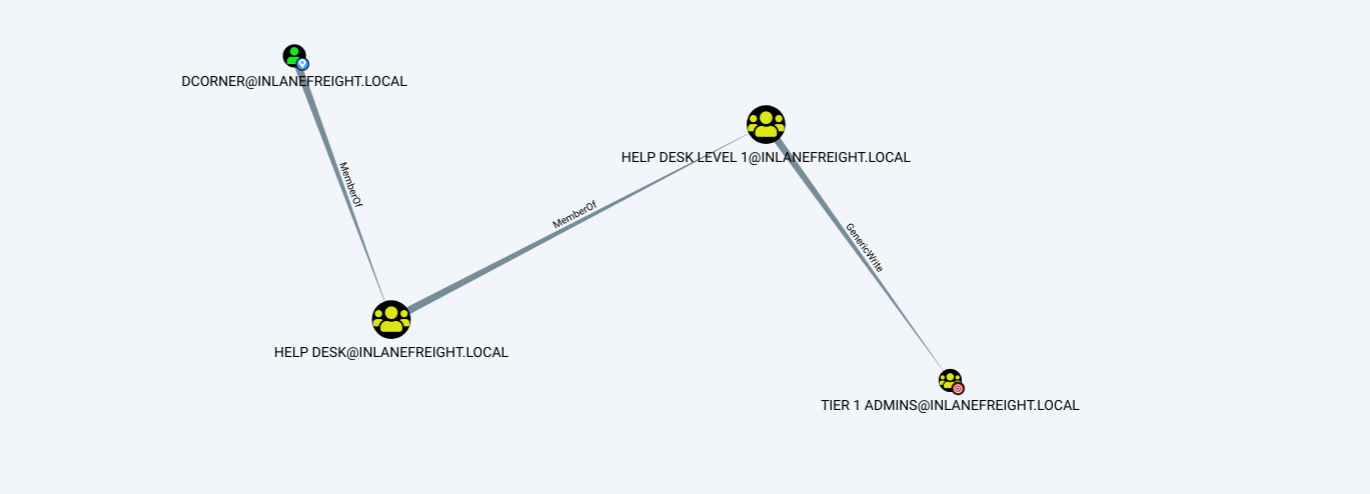

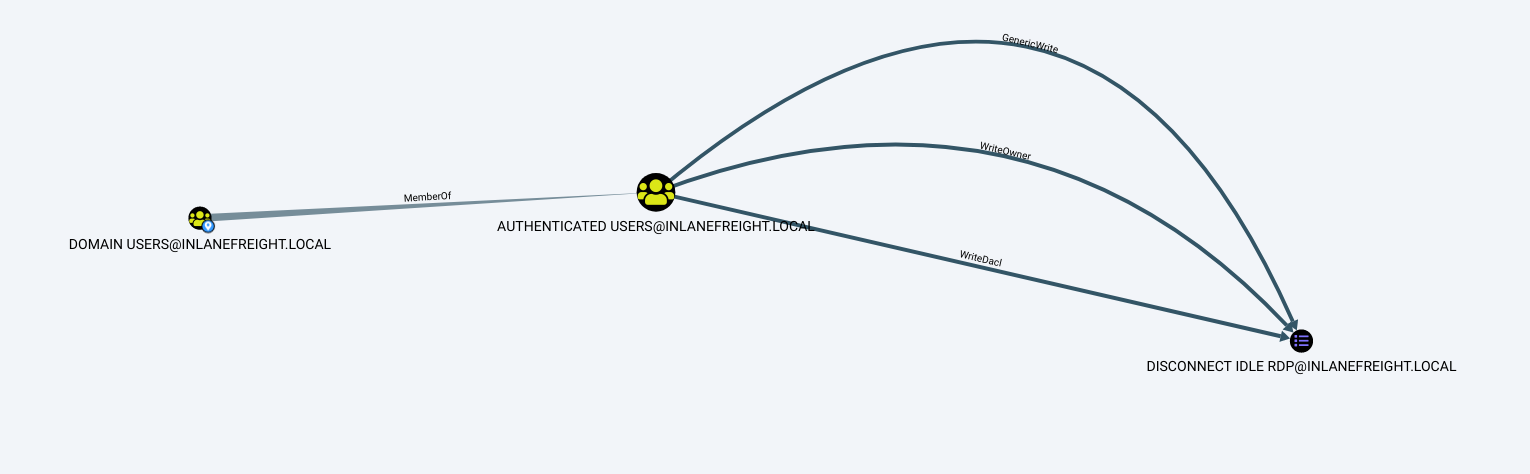

A group is considered a container object because it can contain other objects, including users, computers, and even other groups. A group IS regarded as a security principal and has a SID and a GUID. In AD, groups are a way to manage user permissions and access to other securable objects (both users and computers). Let’s say we want to give 20 help desk users access to the Remote Management Users group on a jump host. Instead of adding the users one by one, we could add the group, and the users would inherit the intended permissions via their membership in the group. In Active Directory, we commonly see what are called “nested groups” (a group added as a member of another group), which can lead to a user(s) obtaining unintended rights. Nested group membership is something we see and often leverage during penetration tests. The tool BloodHound helps to discover attack paths within a network and illustrate them in a graphical interface. It is excellent for auditing group membership and uncovering/seeing the sometimes unintended impacts of nested group membership. Groups in AD can have many attributes, the most common being the name, description, membership, and other groups that the group belongs to. Many other attributes can be set, which we will discuss more in-depth later in this module.

Organizational Units (OUs)

An organizational unit, or OU from here on out, is a container that systems administrators can use to store similar objects for ease of administration. OUs are often used for administrative delegation of tasks without granting a user account full administrative rights. For example, we may have a top-level OU called Employees and then child OUs under it for the various departments such as Marketing, HR, Finance, Help Desk, etc. If an account were given the right to reset passwords over the top-level OU, this user would have the right to reset passwords for all users in the company. However, if the OU structure were such that specific departments were child OUs of the Help Desk OU, then any user placed in the Help Desk OU would have this right delegated to them if granted. Other tasks that may be delegated at the OU level include creating/deleting users, modifying group membership, managing Group Policy links, and performing password resets. OUs are very useful for managing Group Policy (which we will study later in this module) settings across a subset of users and groups within a domain. For example, we may want to set a specific password policy for privileged service accounts so these accounts could be placed in a particular OU and then have a Group Policy object assigned to it, which would enforce this password policy on all accounts placed inside of it. A few OU attributes include its name, members, security settings, and more.

Domain

A domain is the structure of an AD network. Domains contain objects such as users and computers, which are organized into container objects: groups and OUs. Every domain has its own separate database and sets of policies that can be applied to any and all objects within the domain. Some policies are set by default (and can be tweaked), such as the domain password policy. In contrast, others are created and applied based on the organization’s need, such as blocking access to cmd.exe for all non-administrative users or mapping shared drives at log in.

Domain Controllers

Domain Controllers are essentially the brains of an AD network. They handle authentication requests, verify users on the network, and control who can access the various resources in the domain. All access requests are validated via the domain controller and privileged access requests are based on predetermined roles assigned to users. It also enforces security policies and stores information about every other object in the domain.

Sites

A site in AD is a set of computers across one or more subnets connected using high-speed links. They are used to make replication across domain controllers run efficiently.

Built-in

In AD, built-in is a container that holds default groups in an AD domain. They are predefined when an AD domain is created.

Foreign Security Principals

A foreign security principal (FSP) is an object created in AD to represent a security principal that belongs to a trusted external forest. They are created when an object such as a user, group, or computer from an external (outside of the current) forest is added to a group in the current domain. They are created automatically after adding a security principal to a group. Every foreign security principal is a placeholder object that holds the SID of the foreign object (an object that belongs to another forest.) Windows uses this SID to resolve the object’s name via the trust relationship. FSPs are created in a specific container named ForeignSecurityPrincipals with a distinguished name like cn=ForeignSecurityPrincipals,dc=inlanefreight,dc=local.

Active Directory Functionality

As mentioned before, there are five Flexible Single Master Operation (FSMO) roles. These roles can be defined as follows:

| Roles | Description |

|---|---|

Schema Master | This role manages the read/write copy of the AD schema, which defines all attributes that can apply to an object in AD. |

Domain Naming Master | Manages domain names and ensures that two domains of the same name are not created in the same forest. |

Relative ID (RID) Master | The RID Master assigns blocks of RIDs to other DCs within the domain that can be used for new objects. The RID Master helps ensure that multiple objects are not assigned the same SID. Domain object SIDs are the domain SID combined with the RID number assigned to the object to make the unique SID. |

PDC Emulator | The host with this role would be the authoritative DC in the domain and respond to authentication requests, password changes, and manage Group Policy Objects (GPOs). The PDC Emulator also maintains time within the domain. |

Infrastructure Master | This role translates GUIDs, SIDs, and DNs between domains. This role is used in organizations with multiple domains in a single forest. The Infrastructure Master helps them to communicate. If this role is not functioning properly, Access Control Lists (ACLs) will show SIDs instead of fully resolved names. |

Depending on the organization, these roles may be assigned to specific DCs or as defaults each time a new DC is added. Issues with FSMO roles will lead to authentication and authorization difficulties within a domain.

Domain and Forest Functional Levels

Microsoft introduced functional levels to determine the various features and capabilities available in Active Directory Domain Services (AD DS) at the domain and forest level. They are also used to specify which Windows Server operating systems can run a Domain Controller in a domain or forest. This and this article describe both the domain and forest functional levels from Windows 2000 native to Windows Server 2012 R2. Below is a quick overview of the differences in domain functional levels from Windows 2000 native up to Windows Server 2016, aside from all default Active Directory Directory Services features from the level just below it (or just the default AD DS features in the case of Windows 2000 native.)

| Domain Functional Level | Features Available | Supported Domain Controller Operating Systems |

|---|---|---|

| Windows 2000 native | Universal groups for distribution and security groups, group nesting, group conversion (between security and distribution and security groups), SID history. | Windows Server 2008 R2, Windows Server 2008, Windows Server 2003, Windows 2000 |

| Windows Server 2003 | Netdom.exe domain management tool, lastLogonTimestamp attribute introduced, well-known users and computers containers, constrained delegation, selective authentication. | Windows Server 2012 R2, Windows Server 2012, Windows Server 2008 R2, Windows Server 2008, Windows Server 2003 |

| Windows Server 2008 | Distributed File System (DFS) replication support, Advanced Encryption Standard (AES 128 and AES 256) support for the Kerberos protocol, Fine-grained password policies | Windows Server 2012 R2, Windows Server 2012, Windows Server 2008 R2, Windows Server 2008 |

| Windows Server 2008 R2 | Authentication mechanism assurance, Managed Service Accounts | Windows Server 2012 R2, Windows Server 2012, Windows Server 2008 R2 |

| Windows Server 2012 | KDC support for claims, compound authentication, and Kerberos armoring | Windows Server 2012 R2, Windows Server 2012 |

| Windows Server 2012 R2 | Extra protections for members of the Protected Users group, Authentication Policies, Authentication Policy Silos | Windows Server 2012 R2 |

| Windows Server 2016 | Smart card required for interactive logon new Kerberos features and new credential protection features | Windows Server 2019 and Windows Server 2016 |

A new functional level was not added with the release of Windows Server 2019. However, Windows Server 2008 functional level is the minimum requirement for adding Server 2019 Domain Controllers to an environment. Also, the target domain has to use DFS-R for SYSVOL replication.

Forest functional levels have introduced a few key capabilities over the years:

| Version | Capabilities |

|---|---|

Windows Server 2003 | saw the introduction of the forest trust, domain renaming, read-only domain controllers (RODC), and more. |

Windows Server 2008 | All new domains added to the forest default to the Server 2008 domain functional level. No additional new features. |

Windows Server 2008 R2 | Active Directory Recycle Bin provides the ability to restore deleted objects when AD DS is running. |

Windows Server 2012 | All new domains added to the forest default to the Server 2012 domain functional level. No additional new features. |

Windows Server 2012 R2 | All new domains added to the forest default to the Server 2012 R2 domain functional level. No additional new features. |

Windows Server 2016 | Privileged access management (PAM) using Microsoft Identity Manager (MIM). |

Trusts

A trust is used to establish forest-forest or domain-domain authentication, allowing users to access resources in (or administer) another domain outside of the domain their account resides in. A trust creates a link between the authentication systems of two domains.

There are several trust types.

| Trust Type | Description |

|---|---|

Parent-child | Domains within the same forest. The child domain has a two-way transitive trust with the parent domain. |

Cross-link | a trust between child domains to speed up authentication. |

External | A non-transitive trust between two separate domains in separate forests which are not already joined by a forest trust. This type of trust utilizes SID filtering. |

Tree-root | a two-way transitive trust between a forest root domain and a new tree root domain. They are created by design when you set up a new tree root domain within a forest. |

Forest | a transitive trust between two forest root domains. |

Trust Example

Trusts can be transitive or non-transitive.

- A transitive trust means that trust is extended to objects that the child domain trusts.

- In a non-transitive trust, only the child domain itself is trusted.

Trusts can be set up to be one-way or two-way (bidirectional).

- In bidirectional trusts, users from both trusting domains can access resources.

- In a one-way trust, only users in a trusted domain can access resources in a trusting domain, not vice-versa. The direction of trust is opposite to the direction of access.

Often, domain trusts are set up improperly and provide unintended attack paths. Also, trusts set up for ease of use may not be reviewed later for potential security implications. Mergers and acquisitions can result in bidirectional trusts with acquired companies, unknowingly introducing risk into the acquiring company’s environment. It is not uncommon to be able to perform an attack such as Kerberoasting against a domain outside the principal domain and obtain a user that has administrative access within the principal domain.

Kerberos, DNS, LDAP, MSRPC

While Windows operating systems use a variety of protocols to communicate, Active Directory specifically requires Lightweight Directory Access Protocol (LDAP), Microsoft’s version of Kerberos, DNS for authentication and communication, and MSRPC which is the Microsoft implementation of Remote Procedure Call (RPC), an interprocess communication technique used for client-server model-based applications.

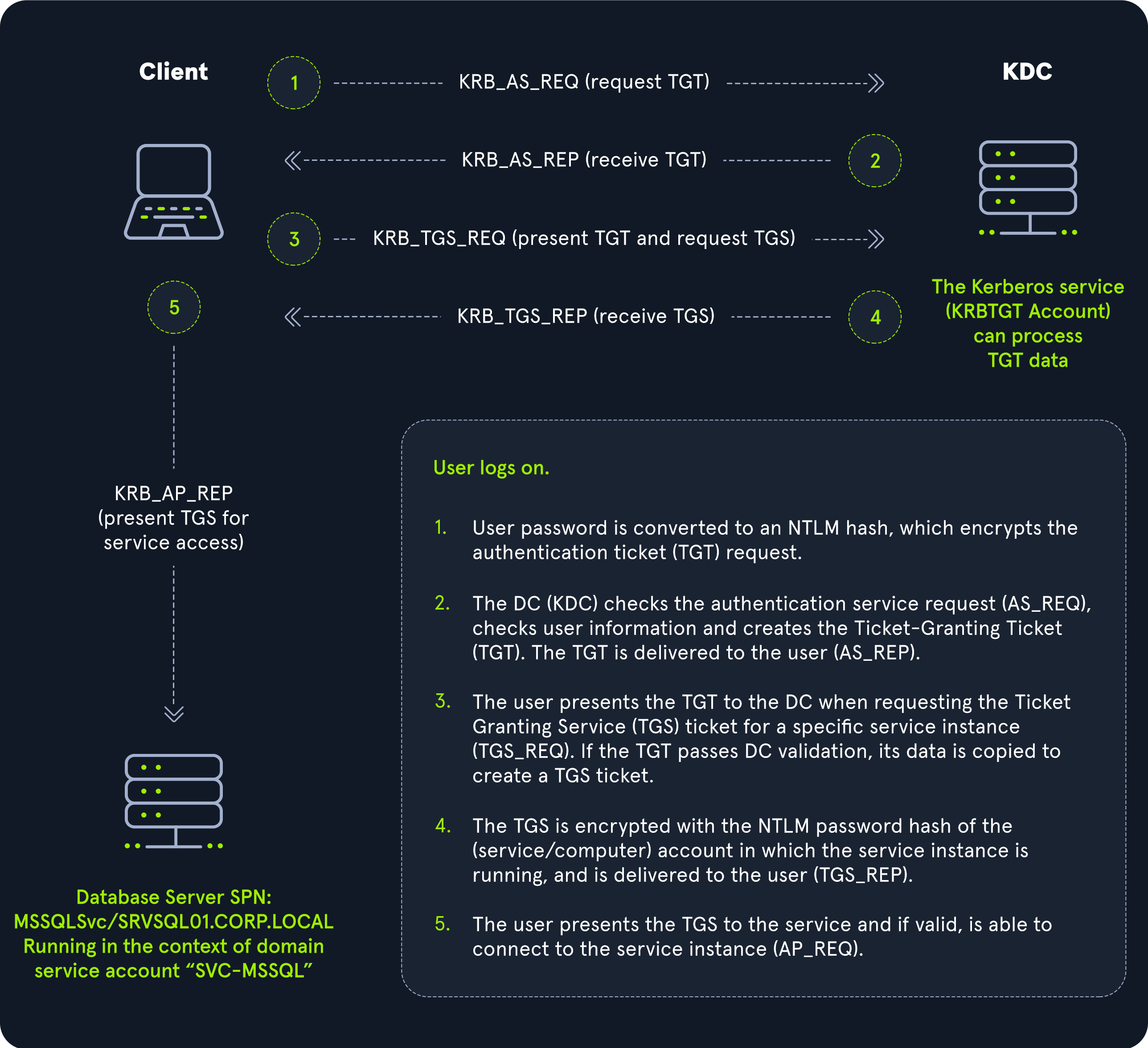

Kerberos

Kerberos has been the default authentication protocol for domain accounts since Windows 2000. Kerberos is an open standard and allows for interoperability with other systems using the same standard. When a user logs into their PC, Kerberos is used to authenticate them via mutual authentication, or both the user and the server verify their identity. Kerberos is a stateless authentication protocol based on tickets instead of transmitting user passwords over the network. As part of Active Directory Domain Services (AD DS), Domain Controllers have a Kerberos Key Distribution Center (KDC) that issues tickets. When a user initiates a login request to a system, the client they are using to authenticate requests a ticket from the KDC, encrypting the request with the user’s password. If the KDC can decrypt the request (AS-REQ) using their password, it will create a Ticket Granting Ticket (TGT) and transmit it to the user. The user then presents its TGT to a Domain Controller to request a Ticket Granting Service (TGS) ticket, encrypted with the associated service’s NTLM password hash. Finally, the client requests access to the required service by presenting the TGS to the application or service, which decrypts it with its password hash. If the entire process completes appropriately, the user will be permitted to access the requested service or application.

Kerberos authentication effectively decouples users’ credentials from their requests to consumable resources, ensuring that their password isn’t transmitted over the network (i.e., accessing an internal SharePoint intranet site). The Kerberos Key Distribution Centre (KDC) does not record previous transactions. Instead, the Kerberos Ticket Granting Service ticket (TGS) relies on a valid Ticket Granting Ticket (TGT). It assumes that if the user has a valid TGT, they must have proven their identity. The following diagram walks through this process at a high level.

Kerberos Authentication Process

| 1. When a user logs in, their password is used to encrypt a timestamp, which is sent to the Key Distribution Center (KDC) to verify the integrity of the authentication by decrypting it. The KDC then issues a Ticket-Granting Ticket (TGT), encrypting it with the secret key of the krbtgt account. This TGT is used to request service tickets for accessing network resources, allowing authentication without repeatedly transmitting the user’s credentials. This process decouples the user’s credentials from requests to resources. |

|---|

| 2. The KDC service on the DC checks the authentication service request (AS-REQ), verifies the user information, and creates a Ticket Granting Ticket (TGT), which is delivered to the user. |

| 3. The user presents the TGT to the DC, requesting a Ticket Granting Service (TGS) ticket for a specific service. This is the TGS-REQ. If the TGT is successfully validated, its data is copied to create a TGS ticket. |

| 4. The TGS is encrypted with the NTLM password hash of the service or computer account in whose context the service instance is running and is delivered to the user in the TGS_REP. |

| 5. The user presents the TGS to the service, and if it is valid, the user is permitted to connect to the resource (AP_REQ). |

|

The Kerberos protocol uses port 88 (both TCP and UDP). When enumerating an Active Directory environment, we can often locate Domain Controllers by performing port scans looking for open port 88 using a tool such as Nmap.

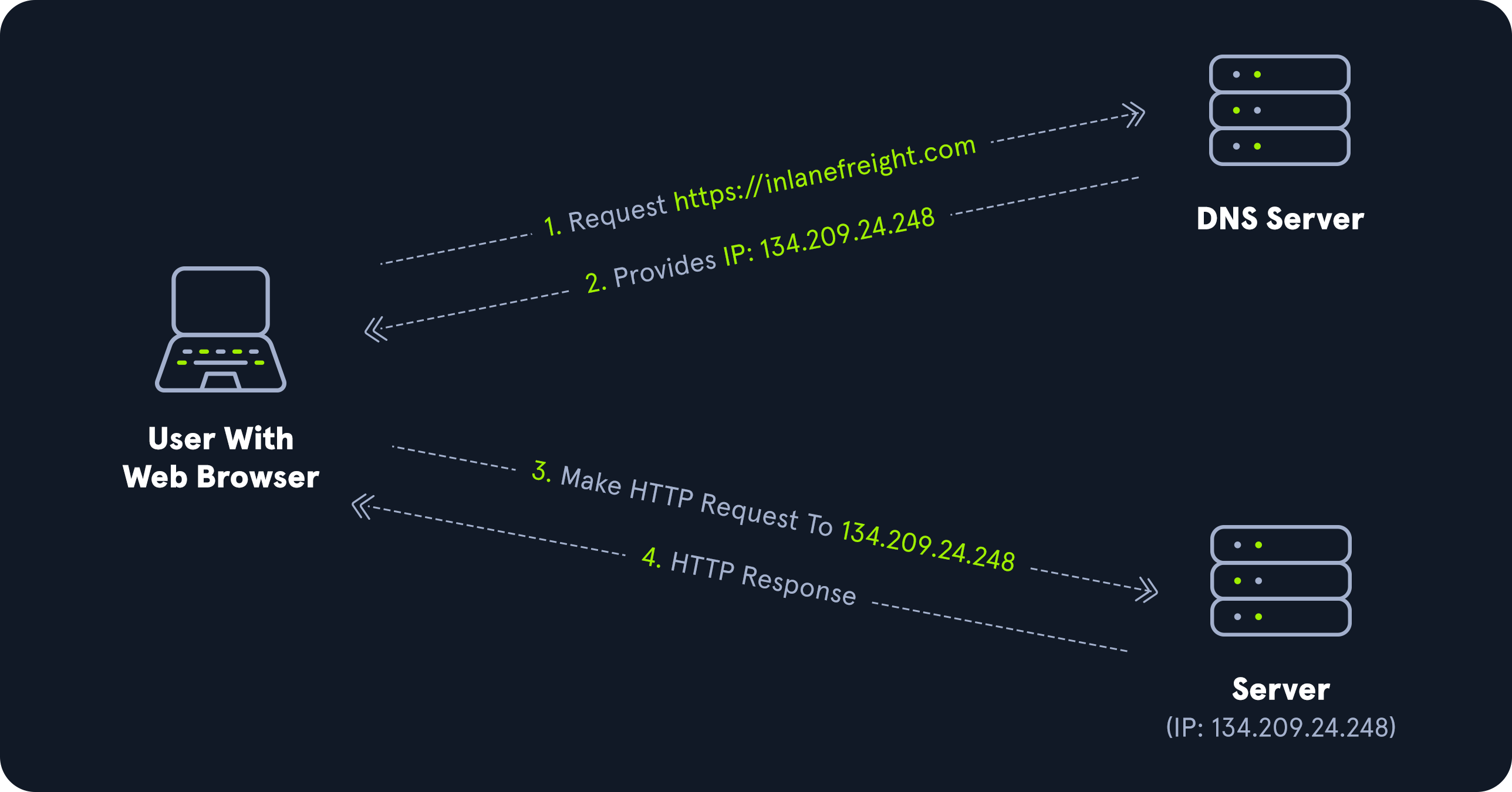

DNS

Active Directory Domain Services (AD DS) uses DNS to allow clients (workstations, servers, and other systems that communicate with the domain) to locate Domain Controllers and for Domain Controllers that host the directory service to communicate amongst themselves. DNS is used to resolve hostnames to IP addresses and is broadly used across internal networks and the internet. Private internal networks use Active Directory DNS namespaces to facilitate communications between servers, clients, and peers. AD maintains a database of services running on the network in the form of service records (SRV). These service records allow clients in an AD environment to locate services that they need, such as a file server, printer, or Domain Controller. Dynamic DNS is used to make changes in the DNS database automatically should a system’s IP address change. Making these entries manually would be very time-consuming and leave room for error. If the DNS database does not have the correct IP address for a host, clients will not be able to locate and communicate with it on the network. When a client joins the network, it locates the Domain Controller by sending a query to the DNS service, retrieving an SRV record from the DNS database, and transmitting the Domain Controller’s hostname to the client. The client then uses this hostname to obtain the IP address of the Domain Controller. DNS uses TCP and UDP port 53. UDP port 53 is the default, but it falls back to TCP when no longer able to communicate and DNS messages are larger than 512 bytes.

Forward DNS Lookup

Let’s look at an example. We can perform a nslookup for the domain name and retrieve all Domain Controllers’ IP addresses in a domain.

PS C:\htb> nslookup INLANEFREIGHT.LOCAL

Server: 172.16.6.5

Address: 172.16.6.5

Name: INLANEFREIGHT.LOCAL

Address: 172.16.6.5Reverse DNS Lookup

If we would like to obtain the DNS name of a single host using the IP address, we can do this as follows:

PS C:\htb> nslookup 172.16.6.5

Server: 172.16.6.5

Address: 172.16.6.5

Name: ACADEMY-EA-DC01.INLANEFREIGHT.LOCAL

Address: 172.16.6.5Finding IP Address of a Host

If we would like to find the IP address of a single host, we can do this in reverse. We can do this with or without specifying the FQDN.

PS C:\htb> nslookup ACADEMY-EA-DC01

Server: 172.16.6.5

Address: 172.16.6.5

Name: ACADEMY-EA-DC01.INLANEFREIGHT.LOCAL

Address: 172.16.6.5For deeper dives into DNS, check out the DNS Enumeration Using Python module and the DNS section of the Information Gathering - Web Edition module.

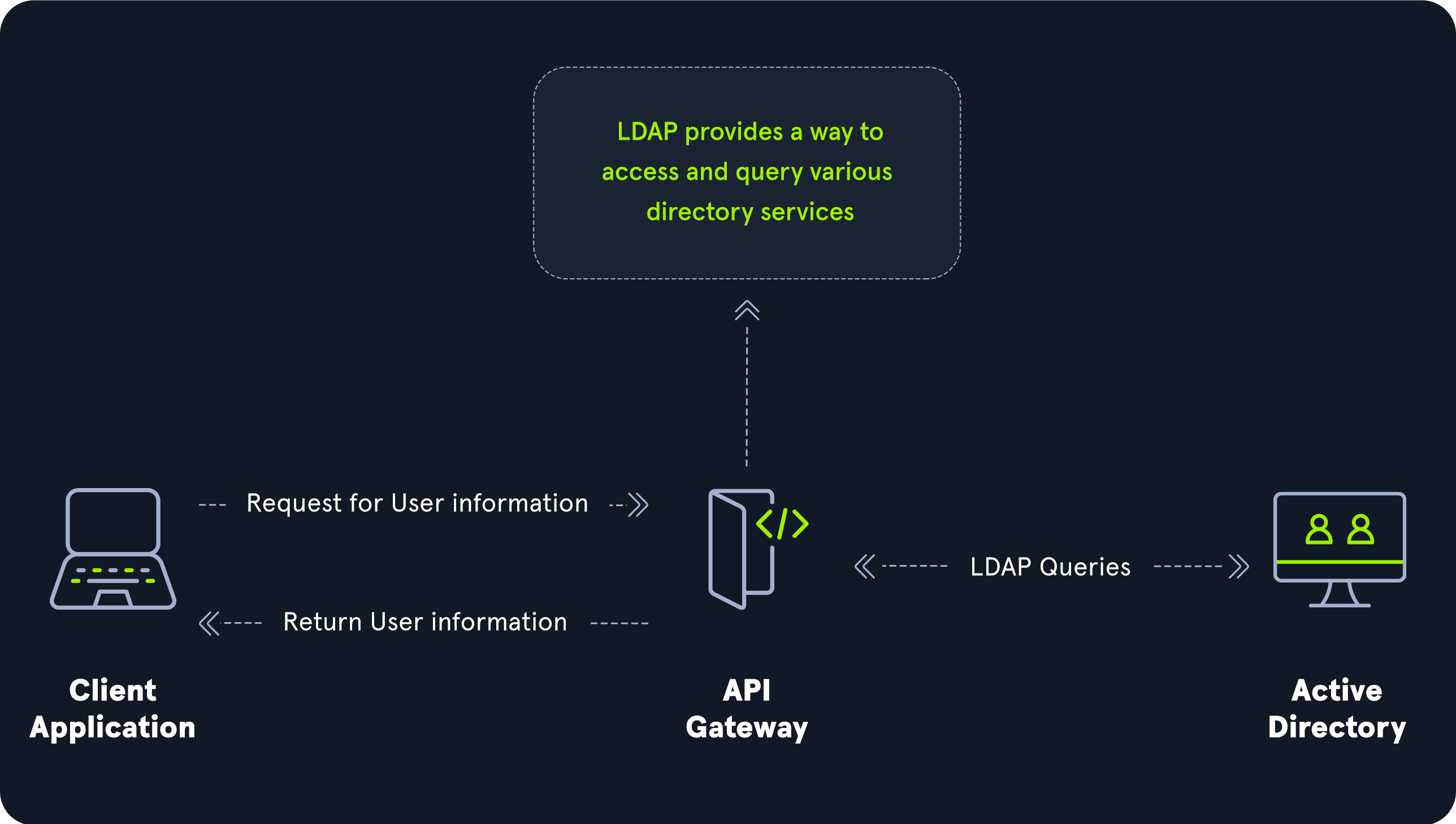

LDAP

Active Directory supports Lightweight Directory Access Protocol (LDAP) for directory lookups. LDAP is an open-source and cross-platform protocol used for authentication against various directory services (such as AD). The latest LDAP specification is Version 3, published as RFC 4511. A firm understanding of how LDAP works in an AD environment is crucial for attackers and defenders. LDAP uses port 389, and LDAP over SSL (LDAPS) communicates over port 636.

AD stores user account information and security information such as passwords and facilitates sharing this information with other devices on the network. LDAP is the language that applications use to communicate with other servers that provide directory services. In other words, LDAP is how systems in the network environment can “speak” to AD.

An LDAP session begins by first connecting to an LDAP server, also known as a Directory System Agent. The Domain Controller in AD actively listens for LDAP requests, such as security authentication requests.

The relationship between AD and LDAP can be compared to Apache and HTTP. The same way Apache is a web server that uses the HTTP protocol, Active Directory is a directory server that uses the LDAP protocol.

While uncommon, you may come across organization while performing an assessment that do not have AD but are using LDAP, meaning that they most likely use another type of LDAP server such as OpenLDAP.

AD LDAP Authentication

LDAP is set up to authenticate credentials against AD using a “BIND” operation to set the authentication state for an LDAP session. There are two types of LDAP authentication.

Simple Authentication: This includes anonymous authentication, unauthenticated authentication, and username/password authentication. Simple authentication means that ausernameandpasswordcreate a BIND request to authenticate to the LDAP server.SASL Authentication: The Simple Authentication and Security Layer (SASL) framework uses other authentication services, such as Kerberos, to bind to the LDAP server and then uses this authentication service (Kerberos in this example) to authenticate to LDAP. The LDAP server uses the LDAP protocol to send an LDAP message to the authorization service, which initiates a series of challenge/response messages resulting in either successful or unsuccessful authentication. SASL can provide additional security due to the separation of authentication methods from application protocols.

LDAP authentication messages are sent in cleartext by default so anyone can sniff out LDAP messages on the internal network. It is recommended to use TLS encryption or similar to safeguard this information in transit.

MSRPC

As mentioned above, MSRPC is Microsoft’s implementation of Remote Procedure Call (RPC), an interprocess communication technique used for client-server model-based applications. Windows systems use MSRPC to access systems in Active Directory using four key RPC interfaces.

| Interface Name | Description |

|---|---|

lsarpc | A set of RPC calls to the Local Security Authority (LSA) system which manages the local security policy on a computer, controls the audit policy, and provides interactive authentication services. LSARPC is used to perform management on domain security policies. |

netlogon | Netlogon is a Windows process used to authenticate users and other services in the domain environment. It is a service that continuously runs in the background. |

samr | Remote SAM (samr) provides management functionality for the domain account database, storing information about users and groups. IT administrators use the protocol to manage users, groups, and computers by enabling admins to create, read, update, and delete information about security principles. Attackers (and pentesters) can use the samr protocol to perform reconnaissance about the internal domain using tools such as BloodHound to visually map out the AD network and create “attack paths” to illustrate visually how administrative access or full domain compromise could be achieved. Organizations can protect against this type of reconnaissance by changing a Windows registry key to only allow administrators to perform remote SAM queries since, by default, all authenticated domain users can make these queries to gather a considerable amount of information about the AD domain. |

drsuapi | drsuapi is the Microsoft API that implements the Directory Replication Service (DRS) Remote Protocol which is used to perform replication-related tasks across Domain Controllers in a multi-DC environment. Attackers can utilize drsuapi to create a copy of the Active Directory domain database (NTDS.dit) file to retrieve password hashes for all accounts in the domain, which can then be used to perform Pass-the-Hash attacks to access more systems or cracked offline using a tool such as Hashcat to obtain the cleartext password to log in to systems using remote management protocols such as Remote Desktop (RDP) and WinRM. |

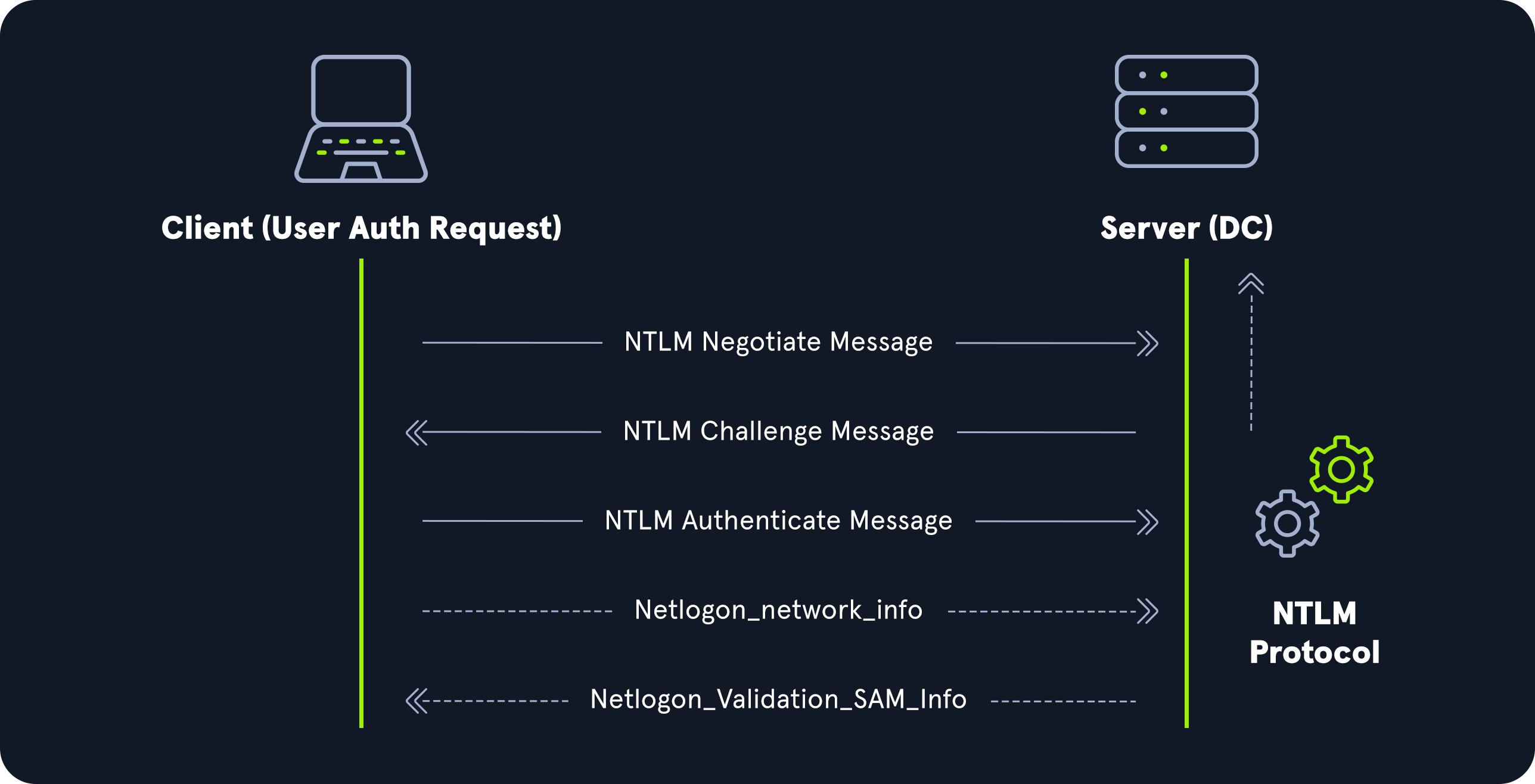

NTLM Authentication

Aside from Kerberos and LDAP, Active Directory uses several other authentication methods which can be used (and abused) by applications and services in AD. These include LM, NTLM, NTLMv1, and NTLMv2. LM and NTLM here are the hash names, and NTLMv1 and NTLMv2 are authentication protocols that utilize the LM or NT hash. Below is a quick comparison between these hashes and protocols, which shows us that, while not perfect by any means, Kerberos is often the authentication protocol of choice wherever possible. It is essential to understand the difference between the hash types and the protocols that use them.

Hash Protocol Comparison

| Hash/Protocol | Cryptographic technique | Mutual Authentication | Message Type | Trusted Third Party |

|---|---|---|---|---|

NTLM | Symmetric key cryptography | No | Random number | Domain Controller |

NTLMv1 | Symmetric key cryptography | No | MD4 hash, random number | Domain Controller |

NTLMv2 | Symmetric key cryptography | No | MD4 hash, random number | Domain Controller |

Kerberos | Symmetric key cryptography & asymmetric cryptography | Yes | Encrypted ticket using DES, MD5 | Domain Controller/Key Distribution Center (KDC) |

LM

LAN Manager (LM or LANMAN) hashes are the oldest password storage mechanism used by the Windows operating system. LM debuted in 1987 on the OS/2 operating system. If in use, they are stored in the SAM database on a Windows host and the NTDS.DIT database on a Domain Controller. Due to significant security weaknesses in the hashing algorithm used for LM hashes, it has been turned off by default since Windows Vista/Server 2008. However, it is still common to encounter, especially in large environments where older systems are still used. Passwords using LM are limited to a maximum of 14 characters. Passwords are not case sensitive and are converted to uppercase before generating the hashed value, limiting the keyspace to a total of 69 characters making it relatively easy to crack these hashes using a tool such as Hashcat.

Before hashing, a 14 character password is first split into two seven-character chunks. If the password is less than fourteen characters, it will be padded with NULL characters to reach the correct value. Two DES keys are created from each chunk. These chunks are then encrypted using the string KGS!@#$%, creating two 8-byte ciphertext values. These two values are then concatenated together, resulting in an LM hash. This hashing algorithm means that an attacker only needs to brute force seven characters twice instead of the entire fourteen characters, making it fast to crack LM hashes on a system with one or more GPUs. If a password is seven characters or less, the second half of the LM hash will always be the same value and could even be determined visually without even needed tools such as Hashcat. The use of LM hashes can be disallowed using Group Policy. An LM hash takes the form of 299bd128c1101fd6.

Note

Windows operating systems prior to Windows Vista and Windows Server 2008 (Windows NT4, Windows 2000, Windows 2003, Windows XP) stored both the LM hash and the NTLM hash of a user’s password by default.

NTHash (NTLM)

NT LAN Manager (NTLM) hashes are used on modern Windows systems. It is a challenge-response authentication protocol and uses three messages to authenticate: a client first sends a NEGOTIATE_MESSAGE to the server, whose response is a CHALLENGE_MESSAGE to verify the client’s identity. Lastly, the client responds with an AUTHENTICATE_MESSAGE. These hashes are stored locally in the SAM database or the NTDS.DIT database file on a Domain Controller. The protocol has two hashed password values to choose from to perform authentication: the LM hash (as discussed above) and the NT hash, which is the MD4 hash of the little-endian UTF-16 value of the password. The algorithm can be visualized as: MD4(UTF-16-LE(password)).

NTLM Authentication Request

Even though they are considerably stronger than LM hashes (supporting the entire Unicode character set of 65,536 characters), they can still be brute-forced offline relatively quickly using a tool such as Hashcat. GPU attacks have shown that the entire NTLM 8 character keyspace can be brute-forced in under 3 hours. Longer NTLM hashes can be more challenging to crack depending on the password chosen, and even long passwords (15+ characters) can be cracked using an offline dictionary attack combined with rules. NTLM is also vulnerable to the pass-the-hash attack, which means an attacker can use just the NTLM hash (after obtaining via another successful attack) to authenticate to target systems where the user is a local admin without needing to know the cleartext value of the password.

An NT hash takes the form of b4b9b02e6f09a9bd760f388b67351e2b, which is the second half of the full NTLM hash. An NTLM hash looks like this:

Rachel:500:aad3c435b514a4eeaad3b935b51304fe:e46b9e548fa0d122de7f59fb6d48eaa2:::Looking at the hash above, we can break the NTLM hash down into its individual parts:

Rachelis the username500is the Relative Identifier (RID). 500 is the known RID for theadministratoraccountaad3c435b514a4eeaad3b935b51304feis the LM hash and, if LM hashes are disabled on the system, can not be used for anythinge46b9e548fa0d122de7f59fb6d48eaa2is the NT hash. This hash can either be cracked offline to reveal the cleartext value (depending on the length/strength of the password) or used for a pass-the-hash attack. Below is an example of a successful pass-the-hash attack using the CrackMapExec tool:

gitblanc@htb[/htb]$ crackmapexec smb 10.129.41.19 -u rachel -H e46b9e548fa0d122de7f59fb6d48eaa2

SMB 10.129.43.9 445 DC01 [*] Windows 10.0 Build 17763 (name:DC01) (domain:INLANEFREIGHT.LOCAL) (signing:True) (SMBv1:False)

SMB 10.129.43.9 445 DC01 [+] INLANEFREIGHT.LOCAL\rachel:e46b9e548fa0d122de7f59fb6d48eaa2 (Pwn3d!)Now that we understand the capabilities and structure of NTLM let’s examine the progression of the protocol through NTLMv1 and NTLMv2.

Note

Neither LANMAN nor NTLM uses a salt.

NTLMv1 (Net-NTLMv1)

The NTLM protocol performs a challenge/response between a server and client using the NT hash. NTLMv1 uses both the NT and the LM hash, which can make it easier to “crack” offline after capturing a hash using a tool such as Responder or via an NTLM relay attack (both of which are out of scope for this module and will be covered in later modules on Lateral Movement). The protocol is used for network authentication, and the Net-NTLMv1 hash itself is created from a challenge/response algorithm. The server sends the client an 8-byte random number (challenge), and the client returns a 24-byte response. These hashes can NOT be used for pass-the-hash attacks. The algorithm looks as follows:

V1 Challenge & Response Algorithm

C = 8-byte server challenge, random

K1 | K2 | K3 = LM/NT-hash | 5-bytes-0

response = DES(K1,C) | DES(K2,C) | DES(K3,C)An example of a full NTLMv1 hash looks like:

NTLMv1 Hash Example

u4-netntlm::kNS:338d08f8e26de93300000000000000000000000000000000:9526fb8c23a90751cdd619b6cea564742e1e4bf33006ba41:cb8086049ec4736cNTLMv1 was the building block for modern NTLM authentication. Like any protocol, it has flaws and is susceptible to cracking and other attacks. Now let us move on and take a look at NTLMv2 and see how it improves on the foundation that version one set.

NTLMv2 (Net-NTLMv2)

The NTLMv2 protocol was first introduced in Windows NT 4.0 SP4 and was created as a stronger alternative to NTLMv1. It has been the default in Windows since Server 2000. It is hardened against certain spoofing attacks that NTLMv1 is susceptible to. NTLMv2 sends two responses to the 8-byte challenge received by the server. These responses contain a 16-byte HMAC-MD5 hash of the challenge, a randomly generated challenge from the client, and an HMAC-MD5 hash of the user’s credentials. A second response is sent, using a variable-length client challenge including the current time, an 8-byte random value, and the domain name. The algorithm is as follows:

V2 Challenge & Response Algorithm

SC = 8-byte server challenge, random

CC = 8-byte client challenge, random

CC* = (X, time, CC2, domain name)

v2-Hash = HMAC-MD5(NT-Hash, user name, domain name)

LMv2 = HMAC-MD5(v2-Hash, SC, CC)

NTv2 = HMAC-MD5(v2-Hash, SC, CC*)

response = LMv2 | CC | NTv2 | CC*An example of an NTLMv2 hash is:

NTLMv2 Hash Example

admin::N46iSNekpT:08ca45b7d7ea58ee:88dcbe4446168966a153a0064958dac6:5c7830315c7830310000000000000b45c67103d07d7b95acd12ffa11230e0000000052920b85f78d013c31cdb3b92f5d765c783030We can see that developers improved upon v1 by making NTLMv2 harder to crack and giving it a more robust algorithm made up of multiple stages. We have one more authentication mechanism to discuss before moving on. This method is of note to us because it does not require a persistent network connection to work.

Domain Cached Credentials (MSCache2)

In an AD environment, the authentication methods mentioned in this section and the previous require the host we are trying to access to communicate with the “brains” of the network, the Domain Controller. Microsoft developed the MS Cache v1 and v2 algorithm (also known as Domain Cached Credentials (DCC) to solve the potential issue of a domain-joined host being unable to communicate with a domain controller (i.e., due to a network outage or other technical issue) and, hence, NTLM/Kerberos authentication not working to access the host in question. Hosts save the last ten hashes for any domain users that successfully log into the machine in the HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\SECURITY\Cache registry key. These hashes cannot be used in pass-the-hash attacks. Furthermore, the hash is very slow to crack with a tool such as Hashcat, even when using an extremely powerful GPU cracking rig, so attempts to crack these hashes typically need to be extremely targeted or rely on a very weak password in use. These hashes can be obtained by an attacker or pentester after gaining local admin access to a host and have the following format: $DCC2$10240#bjones#e4e938d12fe5974dc42a90120bd9c90f. It is vital as penetration testers that we understand the varying types of hashes that we may encounter while assessing an AD environment, their strengths, weaknesses, how they can be abused (cracking to cleartext, pass-the-hash, or relayed), and when an attack may be futile (i.e., spending days attempting to crack a set of Domain Cached Credentials).

Moving On

Now that we have covered authentication protocols and associated password hashes let’s look at users and groups in Active Directory, which are typically the most important target for penetration testers and attackers alike. They can have varying privileges and be used to move laterally in an environment or gain access to protected resources.

User and Machine Accounts

User accounts are created on both local systems (not joined to AD) and in Active Directory to give a person or a program (such as a system service) the ability to log on to a computer and access resources based on their rights. When a user logs in, the system verifies their password and creates an access token. This token describes the security content of a process or thread and includes the user’s security identity and group membership. Whenever a user interacts with a process, this token is presented. User accounts are used to allow employees/contractors to log in to a computer and access resources, to run programs or services under a specific security context (i.e., running as a highly privileged user instead of a network service account), and to manage access to objects and their properties such as network file shares, files, applications, etc. Users can be assigned to groups that can contain one or more members. These groups can also be used to control access to resources. It can be easier for an administrator to assign privileges once to a group (which all group members inherit) instead of many times to each individual user. This helps simplify administration and makes it easier to grant and revoke user rights.

The ability to provision and manage user accounts is one of the core elements of Active Directory. Typically, every company we encounter will have at least one AD user account provisioned per user. Some users may have two or more accounts provisioned based on their job role (i.e., an IT admin or Help Desk member). Aside from standard user and admin accounts tied back to a specific user, we will often see many service accounts used to run a particular application or service in the background or perform other vital functions within the domain environment. An organization with 1,000 employees could have 1,200 active user accounts or more! We may also see organizations with hundreds of disabled accounts from former employees, temporary/seasonal employees, interns, etc. Some companies must retain records of these accounts for audit purposes, so they will deactivate them (and hopefully remove all privileges) once the employee is terminated, but they will not delete them. It is common to see an OU such as FORMER EMPLOYEES that will contain many deactivated accounts.

As we will see later in this module, user accounts can be provisioned many rights in Active Directory. They can be configured as basically read-only users who have read access to most of the environment (which are the permissions a standard Domain User receives) up to Enterprise Admin (with complete control of every object in the domain) and countless combinations in between. Because users can have so many rights assigned to them, they can also be misconfigured relatively easily and granted unintended rights that an attacker or a penetration tester can leverage. User accounts present an immense attack surface and are usually a key focus for gaining a foothold during a penetration test. Users are often the weakest link in any organization. It is difficult to manage human behavior and account for every user choosing weak or shared passwords, installing unauthorized software, or admins making careless mistakes or being overly permissive with account management. To combat this, an organization needs to have policies and procedures to combat issues that can arise around user accounts and must have defense in depth to mitigate the inherent risk that users bring to the domain.

Specifics on user-related misconfigurations and attacks are outside the scope of this module. Still, it is important to understand the sheer impact users can have within any Active Directory network and to understand the nuances between the different types of users/accounts we may encounter.

Local Accounts

Local accounts are stored locally on a particular server or workstation. These accounts can be assigned rights on that host either individually or via group membership. Any rights assigned can only be granted to that specific host and will not work across the domain. Local user accounts are considered security principals but can only manage access to and secure resources on a standalone host. There are several default local user accounts that are created on a Windows system:

Administrator: this account has the SIDS-1-5-domain-500and is the first account created with a new Windows installation. It has full control over almost every resource on the system. It cannot be deleted or locked, but it can be disabled or renamed. Windows 10 and Server 2016 hosts disable the built-in administrator account by default and create another local account in the local administrator’s group during setup.Guest: this account is disabled by default. The purpose of this account is to allow users without an account on the computer to log in temporarily with limited access rights. By default, it has a blank password and is generally recommended to be left disabled because of the security risk of allowing anonymous access to a host.SYSTEM: The SYSTEM (orNT AUTHORITY\SYSTEM) account on a Windows host is the default account installed and used by the operating system to perform many of its internal functions. Unlike the Root account on Linux,SYSTEMis a service account and does not run entirely in the same context as a regular user. Many of the processes and services running on a host are run under the SYSTEM context. One thing to note with this account is that a profile for it does not exist, but it will have permissions over almost everything on the host. It does not appear in User Manager and cannot be added to any groups. ASYSTEMaccount is the highest permission level one can achieve on a Windows host and, by default, is granted Full Control permissions to all files on a Windows system.Network Service: This is a predefined local account used by the Service Control Manager (SCM) for running Windows services. When a service runs in the context of this particular account, it will present credentials to remote services.Local Service: This is another predefined local account used by the Service Control Manager (SCM) for running Windows services. It is configured with minimal privileges on the computer and presents anonymous credentials to the network.

It is worth studying Microsoft’s documentation on local default accounts in-depth to gain a better understanding of how the various accounts work together on an individual Windows system and across a domain network. Take some time to look them over and understand the nuances between them.

Domain Users

Domain users differ from local users in that they are granted rights from the domain to access resources such as file servers, printers, intranet hosts, and other objects based on the permissions granted to their user account or the group that account is a member of. Domain user accounts can log in to any host in the domain, unlike local users. For more information on the many different Active Directory account types, check out this link. One account to keep in mind is the KRBTGT account, however. This is a type of local account built into the AD infrastructure. This account acts as a service account for the Key Distribution service providing authentication and access for domain resources. This account is a common target of many attackers since gaining control or access will enable an attacker to have unconstrained access to the domain. It can be leveraged for privilege escalation and persistence in a domain through attacks such as the Golden Ticket attack.

User Naming Attributes